By Anthony Chammah

“Defiance”

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party, more famously known as the Nazi Party, was in power from 1933 through 1945. The Nazi Party was founded in 1919 upon values of Ultra-Nationalism and anti-Semitism. This political group first rallied together in protest of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, which brought an end to the First World War. The doctored peace treaty stipulated that Germany pay the allied powers the modern equivalent of close to half a trillion dollars. The economic adversity these reparations imposed on Germany served as a major stimulus for the Nazi’s rise to power and prominence. Adolf Hitler, one of the party’s first members, became the party’s leader in 1921 and by 1933, Hitler would become the chancellor of Germany and move on from there to establish a totalitarian police state in Germany. Hitler is most notoriously known for his treatment of minority groups, especially Jews. During World War Two the Nazi Party would kill almost two in three European Jews, over 6,000,000, as part of Hitler’s “Final Solution” to exterminate all minorities and create a single uncontested Aryan race.

In 1942 the German army was waging highly successful military campaigns in Western Europe and Northern Africa, yet Hitler also wanted Russia and Eastern Europe to be brought into The Great Reich. Hitler’s army quickly conquered Ukraine and the capital city of Kiev. The citizens of Kiev were rounded up and forced to listen to the German military decree that imposed new rules upon the population. It was during this this round up that Major Eberhardt of the German Military decided that in order to prevent riots from breaking out amongst the city, he needed to distract the citizens. His idea was to create a football tournament between the Axis soldiers and the Kiev city team.

Major Eberhardt’s action to create football matches between the occupied citizens of Kiev and Axis soldiers speaks to the idea that football is much more than a sport. The citizens of Kiev would create a local team that would serve a much larger purpose than just competing in football matches. This team would defy German law and inspire hope and courage in a population that was under control of the Nazi Regime. The story of “The Death Match” and the aftermath of the match, serves as an outstanding example of how football has a drastic and lasting effect on modern culture and politics.

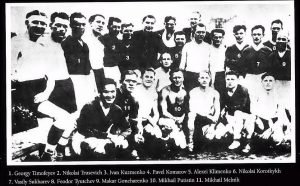

The arrival of war in Ukraine meant the suspension of the football season, so Eberhardt’s tournament between a team comprised of players from two Ukrainian teams and soldiers from Germany, Hungary and Romania in June 1942 marked the return of competitive football for the first time since war broke out. The starting lineup of FC Start, the team comprised of two distinct Ukrainian teams, appeared to consist of bakery workers. However, most of them used to play for the dominant European powerhouse club Dynamo Kiev. The owner of the bakery is thought to have been an avid Dynamo fan and offered extra rations to the players so that they would continue to train. The total number of games FC Start competed in is unclear, but they are thought to have played roughly 7 games, during which they went undefeated. The FC Start starting goalkeeper Nikalai Trusevich said, “We do not have weapons but we can fight with our victories on the football pitch”[1]. FC Start would go on to fight the German soldiers and defend their nation on the football field rather than on the battlefield.

On August 6, 1942 FC Start played the German team Flakelf. There was an estimated 2,000 spectators in attendance, with each spectator paying a total of five rubles to attend. Zenit Stadium was lined with SS soldiers and police dogs as an attempt to intimidate the Start players. The Flakelf team consisted of German soldiers who manned antiaircraft guns around Kiev. FC Start dominated the first game by defeating the Germans 5-1. It is often reported that the Start players faced threats of abuse, harm and even death unless they forfeited the game, but FC Start emerged victorious. Having been humiliated before the entire City, the Germans demanded a rematch three days later on the 9th of August.

Makar Goncharenko, a winger for FC Start, would later give two versions of the match between the Germans and Start. According to the 1985 Goncharenko account, the German team knocked out the start goalkeeper, Trusevich, with a brutal kick to the head. He was then revived yet was heavily discombobulated for the rest of the game. The SS referee did not declare the incident a foul, and after 45 minutes of flagrant offences, FC Start did not think winning would be possible. In Andy Dougan’s book Dynamo, Dougan states, “In that first match even a referee who so clearly favored Flakelf had been unable to protect them from defeat.”[2] While unsure if they could defeat the Germans for a second time, FC Start saw a hope in the second half. After the half, FC Start dominated the field by not only tying the game 3-3, but also scored two goals through their forward Goncharenko, defeating the Germans 5-3 and granting them a second victory.

In 1992, Goncharenko spoke about the match on a Kiev radio station, however this account gave different records of the game. This time, Goncharenko stated that FC Start took the lead 3-1 having gained momentum from the kick to Trusevich’s head before the half. In contrast to his previous statement, Goncharenko denied rumors that at the half, the players of FC Start were visited by an SS officer who warned them that there would be consequences for winning the match and suggested that FC Start should throw the game.

The two humiliating defeats that Flakelf suffered meant much more than the simple loss of a football game. FC Start sported red jerseys, the color most associated with communism, in order to demonstrate that FC Start was not just playing because they were forced to, but instead that they were playing in support of Ukraine. The rematch the Germans called only amplified these narratives of defiance, survival and victory against the Germans. The double victory for FC Start in the face of German threats and a forced rematch gave the Ukrainian people some sort of hope. Before the start of the second game, the team was told by the referee “I am the referee of today’s game. I know you are a very good team. Please follow the rules, do not break any of the rules, and before the game, great your opponents in our fashion”[3]. Instead of giving the Nazi salute, the team gave a popular sportsman’s yell, “Fitness, Culture, Hoorah”. These subtle acts provided to be incredibly inspiring and morale boosting for the Ukrainian people by showing defiance in one of the few ways in which they could.

There is ample speculation on the fate of the team after the match. One rumor indicates that the team was lined up and shot on the field. This is likely false, as there is some evidence of another match FC Start played against Ruhk. On August 18, 1942, the Gestapo arrived at the bakery where the players worked. They issued a list of names of people who were needed for questioning, all three of whom were FC Start players. The Gestapo’s goal was to prove that these three players were a part of the NKVD, a high-level Soviet Law enforcement agency closely associated with it’s Secret Police and Intelligence networks. The Gestapo claimed that they had knowledge of NKVD links to Dynamo Kiev prior to the war and went on to justify all three arrests by producing a picture of one of the players, Nikolai Korotkyh, in an NKVD uniform. He was later tortured to death. It is suggested that the Gestapo also tortured the family members of players in order to gain leverage over the players. There is ample speculation on the fate of the team after the match. One rumor indicates that the team was lined up and shot on the field. This is likely false, as there is some evidence of another match FC Start played against Ruhk. On August 18, 1942, the Gestapo arrived at the bakery where the players worked. They issued a list of names of people who were needed for questioning, all three of whom were FC Start players. The Gestapo’s goal was to prove that these three players were a part of the NKVD, a high-level Soviet Law enforcement agency closely associated with it’s Secret Police and Intelligence networks. The Gestapo claimed that they had knowledge of NKVD links to Dynamo Kiev prior to the war and went on to justify all three arrests by producing a picture of one of the players, Nikolai Korotkyh, in an NKVD uniform. He was later tortured to death. It is suggested that the Gestapo also tortured the family members of players in order to gain leverage over the players.

The rest of the team was sent to a concentration camp at Syrets. After only six months, Alexei Lkimenko, Ivan Kuzmenko and Nikolai Trusevich, were sentenced to death. The reason for their deaths is uncertain, but there are claims that it was in response to attacks by Soviet partisans on the German Armed Forces. Alternatively, it is theorized that perhaps this was simply a case of prisoner abuse. It is speculated that Trusevich was wearing his FC Start goalkeeping top in the last moments of his life, intended to be mockery of the guards at the camps. Feodor Tyutchev, Makhail Sviridovsky and Makar Goncharenko, other FC Start players, managed to escape Syrets with their lives.

After the war, the Soviet government did not acknowledge the courageous acts of FC Start due to the suspicion that even through mere participation in these games, the Ukrainian players could be seen as Nazi collaborators. It was not until the late 1950’s that the Soviet government realized that they could use FC Start to further spread communism through their courageous story. The Soviet plan was originally to pretend that only the “Death Match”, which took place on August 9th, had been played and that all the other games had not. The truth started to emerge with the publications of the story in a Kiev newspaper and in the book “The Final Duel”. Following these publications, movies started to be created about the match and were released in the Soviet Union and Hungary. It became very clear that the government was going to use these events to serve as a Soviet propaganda tool. The government started embracing, accepting and even inventing some of the myths that have been told about the FC Start players, such as that the entire team was immediately shot after the game for their political beliefs. In Goncharenko’s 1985 account of the game, he stated that Trusevich’s last words were “long live Stalin, long live Soviet Sport”[4]. While Trusevich’s last words cannot be proven with accuracy, it is thought Goncharenko may have made modifications to his story so that it better suited the Soviet narrative, thus gaining their permission for publication, or was perhaps altered to avoid reprisal from the Soviets.

It was not until the Soviet Union started to fall apart that more believable depictions of the match started to emerge. In Georgi Kuzmin’s interview with Goncharenko in 1991, he was told that no one asked FC Start to throw the game nor did he believe that any FC Start player was deliberately killed for winning the game. “A desperate fight for survival started which ended badly for four players… Unfortunately they did not die because they were great footballers, or great Dynamo players. They died like many other Soviet people because two totalitarian systems were fighting each other, and they were destined to become victims of that grand scale massacre. The death of the Dynamo players is not so very different from many other deaths”.[5] It wasn’t until 20 years after the “Death Match” that the players who participated were awarded medals for their supposed acts of ‘courage.’ However, Mikhail Putistin refused to accept his medal, claiming that he did not want to take part in a lie.

It will always be impossible to determine the reality behind the lies that were told regarding the matches played between FC Start and Flakelf. As a first step one must examine the time frame in which these stories were told. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the stories of the match greatly differed from when the USSR was in power. Goncharenko’s 1991 account shows that he and many others may have been forced into verifying Soviet propaganda of the match. The Soviet Union used the matches to enhance their political favor amongst civilians. The Soviets’ believed that if they could convince the public that the FC Start players were willing to die for communism by defying German order on the football field, they could inspire hope and prosperity for their government. Even today football has a large impact on the world we live in today. Football players are admired and their opinions are respected. Similarly today as it was in the 1950’s, the Soviet Union would use the people’s love of the game to their political advantage.

Today Zenit Stadium, now called Start Stadium, hosts amateur and semiprofessional football matches during the summer. The football field has a track lining its perimeter that is used for recreational purposes by children and athletes. On the outskirts of the stadium there is a statue honoring the memory of the games in which these players showed tremendous amounts of bravery. At the Dynamo Stadium in Kiev there is another monument honoring the four FC Start players that were killed in the months following the match. The monument depicts the four players standing bravely, shirtless and holding hands. The purpose of this monument is not to bring remorse or anger to those that suffered, but instead to celebrate their lives and remember the strength and bravery these players gave to the city of Kiev.

Although the true story may have been lost within the misconstrued stories and half-truths of Soviet propaganda, it is certain that the FC Start team showed tremendous amounts of fortitude by competing against the oppressive Nazi regime. It cannot be determined whether or not the German regime threatened or persecuted the players in the months after the “Death Match.” The truth behind the events is muddled with the passing of the FC Start players. When reviewing the stories told by eyewitnesses and players, one must keep in mind the motive the Soviet Union had to use this match to their advantage. The memory of the “Death Match” lives on not through the movies that depict a false ending, but through the values for which these courageous players fought, played and perhaps even bled.

Bibliography

Dougan, Andy. Dynamo: Defending the Honour of Kiev. London: Fourth Estate, 2001. Print.

Longman, Jeré, and Andrew W. Lehren. “World War II Soccer Match Echoes Through Time.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 23 June 2012. Web. 8 Apr. 2016.

“Match of Death | Legendary ‘Game of Death’ Football Match in Kiev.” Match of Death | Legendary ‘Game of Death’ Football Match in Kiev. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Apr. 2016.

“1942 – ‘Death Match’.” Euronews. N.p., 22 May 2012. Web. 8 Apr. 2016.

Gregorovich, Andrew. “Dynamo vs Germany: Soccer Match of Death – World War II in Ukraine:.” Dynamo vs Germany: Soccer Match of Death – World War II in Ukraine:. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Apr. 2016.

Person, and Thariq Amir. “The Death Match: Looking Back At The Legendary Game Between FC Start And Flakelf.” World Soccer Talk. N.p., 08 Aug. 2014. Web. 8 Apr. 2016.

[1] World soccer

[2] Dynamo

[3] Local life

[4] World soccer

[5] World soccer