By Basil Seif

Brazil: More than Soccer, Samba, and Carnival

Throughout the history of this beautiful, mystical country, several cultural norms have defined Brazil from generation to generation, not only for Brazilians, but also for the rest of the world: the beautiful game, the Samba, Carnival, Copacabana Beach, the Amazon, and, of course, the favelas. Now, in 2013, it seems that two of these defining characteristics of Brazilian culture are at odds. With the 2014 World Cup several short months away from making landfall in Brazil, the beautiful game is, in a not-so-beautiful way, slowly but surely chipping at the rich favela demographic that makes up much of the backbone of Brazilian society.

Favela History

The favelas were first created in 1897 in Rio de Janeiro by Brazilian veterans of the Canudos war, a Brazilian civil war [4]. As the early 1900s progressed, the favelas started becoming more and more a way for self-starting urban migrants to deal with Rio’s lack of affordable housing [4]. The growth of favelas in wealthier neighborhoods was inevitable as poor people needed to live near their workplace [5]. With unreliable trains and trams the only transportation between Rio and its poorer outskirts, wealthy employers could not afford to wait hours for their employees to arrive [5]. Although the favelas served as good makeshift residences for the poorer classes, they sparked a profound curiosity and almost fear in the rest of Rio’s residents [5]. In fact, in 1927, when Rio hired the French architect Alfred Agache to restructure urban development, his only idea that really resonated in the city was that the favelas needed to be eliminated [5].

In 1937, the Brazilian government issued a building code delcaring these favelas “aberrations” and proceeded to extract most of the residents in the favelas to “proletariat parks,” which were complete with guards to check identity cards and gates that closed at 10pm each night [4]. Inevitably these parks were closed and patterns of unstable housing for the poor majority continued well into the 1940s and beyond, making the favelas a necessity [4]. However, this did not stop the government’s forcible removal of people from the favelas.

By 1965, 30,000 people had been taken out of the favelas. This number skyrocketed between 1968 and 1975, during which time 176,000 people were removed. Many of the favelas were burned down by the Brazilian government after these high volume extractions [5]. Despite these high levels of extraction and destruction of the favelas, these impoverished living communities were still growing at exponential rates. In 1974, the government gave up on the eradication plan without adopting any other official policy on favelas, essentially leaving the communities to their own devices [5].

Over time, the favelas evolved from flimsy shacks to brick constructions with tile roofs, and in 1993, the Executive Group for Low-Income Settlements (GEAP) was founded [4]. GEAP laid the foundation for housing policies and defined urban living as a civic right, a right that society should provide for all Brazilians [5].

Today, Rio has thousands of favelas, in which 20% of the city’s residents live [5]. Some of the most famous favelas are Cidade de Deus (City of God), Vidigal, Santa Marta, and Rocinha. The favelas have always been the physical expression between “rich and poor, black and white, slaves and slave-owners” [5].

In recent years, however, the favelas fell under the command of criminal groups that deal in drug trafficking, groups that have existed in Rio since 1970 [5]. While only 1% of the population in the favelas is involved in drug trafficking, all of the residents suffer from the consequences associated to said violence [5]. In recent years, local hospitals within and around the favelas would deal with an average of 120 bullet wounds a night [7].

Despite the violence among the favelas, these small Brazilian shantytowns harbor some of the richest Brazilian culture that the South American country has to offer.

Famous Players from Favelas

The favelas hold particular significance to the footballing culture in Brazil, especially because some of the greatest Brazilian footballers are cariocas, who grew up playing and watching football in and around the Rio favelas.

Ronaldo Luis Nazario de Lima, better known to the rest of the world as Ronaldo, was born near the favelas of Rio de Janeiro on September 18, 1976 [8]. The youngest of three siblings, Ronaldo began his football career by playing football for various small youth clubs in Rio [8]. At the age of 12, Ronaldo dropped out of school and joined the Social Ramos indoor soccer team before moving to the historic Rio club Sao Cristovao, where he was discovered as a budding young Brazilian star [9]. After his stint at Sao Cristovao, Ronaldo joined his first professional club, Cruzeiro, located in the city of Belo Horizonte [9]. Ronaldo rose to the spotlight during his time at Cruzeiro, leading the club to its first Brazil Cup championship ever, in 1993 [9]. A talented 17-year-old leading a small town club to its first Brazil Cup championship was enough to catch the eye of the Brazilian national team. At the tender age of 17, Ronaldo was called up for the 1994 World Cup in the United States, never playing a minute in the world sporting spectacle and watching his teammates rise to the apex of the sporting world [9]. After the World Cup, in 1994, Ronaldo was transferred to PSV Eindhoven in the Netherlands, where he averaged nearly a goal per game against some of the best European teams in the world. Followed by a one year transfer to FC Barcelona, Ronaldo moved to Internazionale Milan for four years, winning two FIFA World Player of the Year awards. In these years, Ronaldo became one of the greatest players and strikers in the world, “possessing an unstoppable combination of speed and power, equally capable of plowing through defenders as he was of nimbly sidestepping their attacks and accelerating away” [9]. Despite one of the most epic individual choking performances in the history of sports during the final of the 1998 World Cup against France, Ronaldo rebounded from embarrassment and injury to lead Brazil to 2002 World Cup glory. Ronaldo, one of the most famous cariocas of all time, will forever live in Brazilian lore as one of the greatest football players of all time.

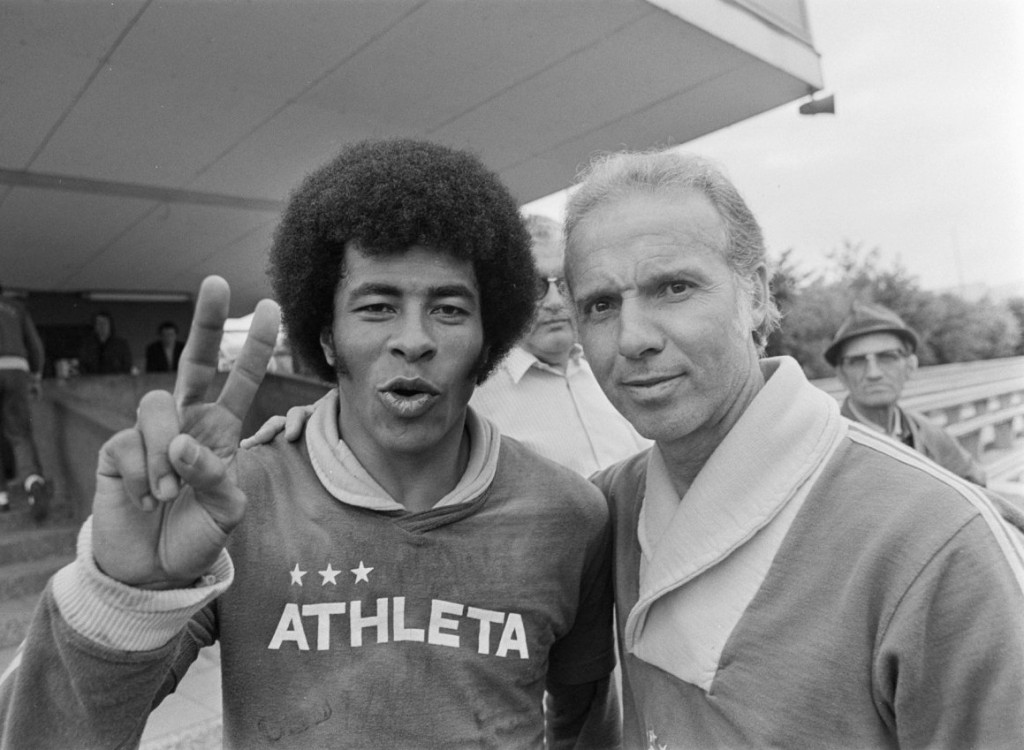

Zico:

Arthur Antunes Coimbra, ketter known to the rest of the world as Zico, is a Brazilian coach and former professional footballer. Zico, also known by many as “the white Pele,” was one of the greatest playmakers that ever played football [10]. He was born on March 3, 1953 to a middle class family in Rio de Janeiro [10]. Growing up, he played football around the famous favelas with the goal to become a professional footballer. In 1967, he was offered a trial by America, a club where his two brothers were playing at the time [10]. Instead of joining America, he joined Flamengo’s youth team in 1971 scoring 81 goals in 116 matches for the youth team [10]. As a senior player for the club, he led the team to four national titles, the Libertadores Cup, and the Intercontinental Cup [10]. After 12 successful years with Flamengo, Zico joined Udinese Calcio, scoring 19 goals in his first of two season with the team, despite not winning any trophies [10]. Zico returned to Flamengo in 1985 a shell of the player he once was, due to injury; despite this reality, he is still the highest goal-scorer in Flamengo history with 508 career goals for the club [10]. Internationally, Zico is often called “the best Brazilian footballer never to lift the World Cup trophy” and played on arguably “the best Brazil squad of all time” [10].

Romario de Souza Faria, better known as just Romario, was born in the Jacarezinho favela in Rio de Janeiro, which, according to Romario, “was a very poor neighborhood” [12]. After three years of living in Jacarezinho, Romario and his family moved to another favela neighborhood, Vila de Penha, where his father started a kid’s team called “estrelinha” [12]. In 1981, Romario was integrated into the youth system of the legendary Rio club, Vasco de Gama, where he climbed the ranks of the club for five years and was eventually promoted to the first team in 1985 [11]. After playing three years for the senior Vasco de Gama team, Romario was transferred to PSV Eindhoven, where manager Guus Hiddink described the ambidextrous Brazilian as “the most interesting player I ever worked with” [11]. At PSV he won the league three out of four seasons and was then transferred to Barcelona, where he won two Spanish league titles and became a Barcelona legend [11]. In 1994, Romario led Brazil to the World Cup title and won the honor of best player of the tournament, scoring five goals [11]. In fact, Romario, with 55 international goals, is the third highest scorer in Brazilian naitonal team history, behind Pele and Ronaldo [11]. Fresh off of a World Cup victory, Romario went back to Brazil and jumped around from club to club, eventually returning to Vasco de Gama and retiring in 2008 as one of the greatest Brazilian players in history [11].

Jair Ventura Filho, better known as Jairzinho, was born in Rio de Janeiro near the favelas on December 25, 1944. Jairzinho began his fledgling career with Brazilian club Botafogo and eventually got a chance to start with the club when Garrinchia, the legend, fell to injury [13]. Jairzinho is most notable, however, for being the only player to score in every round including the final of a World Cup, a feat he accomplished in Mexico in the 1970 World Cup [13]. In this World Cup, Jairzinho once again replaced Garrinchia, who, this time, had retired from international football [13]. Today, Jairzinho is a legend in the favelas for the free football training he offers to poor carioca youngsters, who are seeking an escape through football [14].

Favela Politics

In the wake of both the 2014 World Cup in Brazil and the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, many Brazilians believe that these two sporting spectacles are being used as a pretext for “social cleansing,” as tens of thousands of Rio slum dwellers are being driven out to the city periphery [6]. On top of giving the legendary Maracana stadium a $500 million face-lift, the Brazilian government is building new roads, while also demolishing dozens of favelas for public use [1].

Pierre Batista, Rio de Janeiro’s secretary of housing, estimates that about 20,000 people in Rio have been forced out of the favelas since 2009. Advocates of favela families have estimated a displacement of around 170,000 people [1]. A new report argues that 19,000 families have been moved to make way for roads, renovated stadiums, an athletes’ village, an ambitious redevleopment of the port area, and other projects that have been started to prepare for two of the biggest sporting events in Rio’s history [6].

This entire process of the Brazilian government forcing people out of the favelas, although demographically necessary for the respective successes of the World Cup and the Olympics, goes against the adopted Brazilian ethical code established by GEAP in 1993. According to GEAP and according to cultural norms in Brazil over the past decade, particularly throughout the past 20 years, urban living is a civic right in Brazil [5]. Although many of these intrustions aim to stop gangs, drug violence, and a threat of a so-called “World Cup of Terror,” these raids are still affecting plent of poor Brazilian residents, who feel like they have a right to urban residence [15]. Maria de Socorro, a resident of the Indian favela in Rio whose house of 40 years has been marked for demolition, stood before the city council of Rio in early December to say, “The authorities wouldn’t even enter our community in the past and there was no mention of moving us, but then Brazil won the right to host the World Cup and everything changed” [6].

There is plenty of discussion in Brazil about the ethics of kicking people out of the favelas. The question remains: has the ethical norm changed forever, in regards to urban living, or does the overall benefit to Brazilian citizens of hosting two monumentous sporting events allow Brazilian leaders to make some exceptions and take advantage of the living situations of a certain amount of poorer families? Whether there is a cultural shift in the ethics of urban living in Brazil or the country’s leaders are simply making exceptions for these enormous sporting events, people are nonetheless being moved “from their homes with very little prior notice and no compensation” [6]. According to Renata Neder, of Amnesty International, ” There is a process of gentrification taking place in the whole city that is connected to the sports events and how the government sees the city: it is no longer a place for residents, but as a business to sell to foreign investors. That’s what the World Cup is about” [6].

Despite the overall dissent of many Brazilians to Rio’s resettlement program, this programs seems much smaller scale and less intrusive, in comparison to similar programs in countries hosting the World Cup or Olympic Games, like China in 2008 and South Africa in 2010 [1]. Whether it is the relative cultural importance of the favelas, the density of Rio in comparison to Beijing and South Africa, a comparatively stronger Brazilian urban living ethic, or simply FIFA and Brazil doing a little bit better job of minimizing state intrusion, the fact remains that host nations all over the world, the World Cup, and FIFA, as a so-called globally charitable organization, must do a better job of making sure that the world’s favorite sport, the beautiful game, is not a destructive, but an uplifting force to impoverished fans of this globally unifying sport. As Eduardo Galeano once wrote, “And one fine day the goddess of the wind kisses the foot of man, that mistreated, scorned foot, and from that kiss the soccer idol is born. He is born in a straw crib in a tin-roofed shack and he enters the world clinging to a ball.” Brazil better not destroy the wrong “tin-roofed shack.”

How to cite this page: “The Favela,” Written by Basil Seif (2013), World Cup 2014, Soccer Politics Blog, Duke University, http://sites.duke.edu/wcwp/world-cup-2014/politics-in-brazil/the-favela/ (accessed on (date)).

Sources

[1] Didziulis, Vytenis. “World Cup Blamed for Favela Evictions in Rio De Janeiro.” Fusion. Yahoo! – ABC News Network, 25 Oct. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://fusion.net/abc_univision/news/story/brazils-2014-world-soccer-cup-blamed-favela-evictions-17804>.

[2] Watts, Jonathan. “World Cup 2014: Rio’s Favela Pacification Turns into Slick Operation.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 08 Oct. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/07/2014-world-cup-rio-favela-pacification>.

[3] Craggs, Ryan. “Rio Favela Development: Brazilian Slums Turn From No-Go To Must-Buy.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 13 Jan. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/01/13/rio-favela-development-brazil-slums_n_2467975.html>.

[4] “A History of Favela Upgrades Part I: 1897-1988.” RioOnWatch. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://rioonwatch.org/?p=5295>.

[5] “The Origins of Favelas.” Soul Brasileiro. Soul Brasileiro, n.d. Web. 08 Dec. 2013. <http://soulbrasileiro.com/historia-categoria/the-origins-of-favelas/>.

[6] Watts, Jonathan, and Owen Gibson. “World Cup: Rio Favelas Being ‘socially Cleansed’ in Runup to Sporting Events.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 06 Dec. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/05/world-cup-favelas-socially-cleansed-olympics>.

[7] Smith, Ben. “Confederations Cup: Rio De Janeiro Slums Offered Rebirth.” BBC Sports. BBC, 21 June 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.bbc.com/sport/0/football/22951694>.

[8] “Ronaldo: Personal Life.” Soccer Politics / The Politics of Football. Duke WordPress Sites, n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://sites.duke.edu/wcwp/research-projects/brazil/ronaldo/personal-life/>.

[9] “Ronaldo Biography.” Bio.com. A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.biography.com/people/ronaldo-9463212>.

[10] Henke, Sebastian. “Zico Biography.” History of Soccer. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.history-of-soccer.org/zico.html>.

[11] “Romário Biography.” History of Soccer. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.history-of-soccer.org/romario.html>.

[12] “Romário – a History of Talent.” Globo TV Sports. N.p., 20 Apr. 2006. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://redeglobo.globo.com/Globotvsports/0,27723,LGO0-5387-223671,00.html>.

[13] “Jairzinho.” Planet World Cup – Legends. Planet World Cup, n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.planetworldcup.com/LEGENDS/jair.html>.

[14] Lines, Andy. “The Old Boy from Brazil – World Cup Hero Jairzinho on Helping Rio’s Slum Kids.” Mirror.co.uk. Mirror News, 15 Nov. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/brazilian-world-cup-legend-jairzinho-2792333>.

[15] France-Presse, Agence. “A ‘World Cup of Terror’ Coming to Brazil If Crime Bosses Prevail | The Raw Story.” The Raw Story. Raw Story Media, Inc., 19 Oct. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2013. <http://www.rawstory.com/rs/2013/10/19/a-world-cup-of-terror-coming-to-brazil-if-crime-bosses-prevail/>.

Pingback: Soccer Politics / The Politics of Football » Soccer as an Escape in Brazilian Favelas

I think that many of Brazil’s most famous players grew up in the favela-Pele, for instance grew up inabject poverty (though maybe not a favela)

I recently watched a Brazilian film called the City of God, which depicts a slum in Rio during the 60s and 70s. This movie might be a nice reference for you, or you could just mention it as something to provide some historical background for those reading your post.