Written by Hyun Moh (John) Shin

Intro/Ranking

Currently ranked as 4th by FIFA, Japan women’s soccer team has established itself as one of the top teams among international women’s soccer. Its recent rounds of glory – winning the 2011 Women’s World Cup, reaching the finals in the 2012 London Olympics before crowned as champions of the 2014 AFC Women’s Asian Cup – had given the Nadeshiko Japans “Queen of Asia” status; most of such glory are undoubtedly credited towards its women’s soccer league, the L. League. This page is intended to explore the origins, the format, and the dynamics of the L. League, in order to familiarize those interested in the women’s soccer leagues.

History

The history of women’s soccer competition in Japan started in the 1960s, with women’s soccer team emerging among elementary and middle school students. A number of these forerunner teams, including the women teams in Fukizumi Elementary and Kobe Junior High, gathered in 1967 to participate in the “1st Kobe Soccer Carnival”(第1回神戸サッカーカーニバル) [1], which is currently known to be one of if not the earliest form of women’s soccer competition in Japan.

The official women’s soccer competition occurred during the 70s and mid-80s, in which more women’s soccer teams continued to emerge in Japan, notably in Kansai, or western region of Japan’s main island, Honshuu. Powered by the steady upsurge of women’s team among secondary schools, the Japanese Football Association (JFA) proposed to open the Japan Women’s Soccer National Tournament (全日本女子サッカー選手権大会)[2], consisting of women’s soccer teams in middle schools, high schools, and professional soccer clubs. The first tournament, held in March, 1980, had 8 teams participating in single-game knockout rounds. Each match was played with 8 players per team, in a pitch size of 54m x 76m dimension – about 2/3 the size of the men’s pitch – for two 25-minute halves, with 20-minute extra time and a penalty-shootout if the score ended in a draw.

A Poster for the Empress’ Cup in 2015

Image Credit:[a] , Direct Link

The tournament, later renamed as Empress’s Cup in 2012, continued every year since its first, adjusting the regulation along its ways. The currently held Women’s Soccer National Tournament has 36 teams participating – 10 from the Nadeshiko League, 26 from teams selected through regional competitions – and follows the same in-game rules with that of the men’s soccer matches. Its continued success in drawing interests of the Japanese soccer fans to the women’s soccer is widely regarded by many soccer communities in Japan as one of the major contributions of the development of the L. League.

The L. League itself was founded in 1989, initially as Japan Ladies’ Football League (JLSL, 日本女子サッカーリーグ); boosted by FIFA’s decision to include women’s soccer in the 1990 Asian Cup, as well as the prospect of the 1991 Women’s World Cup in China, the JFA quickly established the JLSL to further appeal to the new pool of audience who were just introduced to the news of Women’s World Cup. Following a series of ups and downs, as well as the crisis era dawned from a series of poor national team performances[3], the JLSL finally attracted a resurgence of fans and spectators after the national women’s soccer team made into the quarterfinals of the Athens Olympics in 2004.

In search of a new nickname for their new hero, the JFA ran a public vote among the soccer fans, and the nickname “Nadeshiko” was chosen to be used in both the national women’s team and the L. League. The term is taken from Yamato Nadeshiko, a Japanese personification of an “ideal women”. It is meant as a parallel to the Samurai Blues, the nickname for their male counterpart. Backed up by the recent success of the women’s national team in the World Cup and the Asian Cup, the “Nadeshiko League” has persisted for over 10 years, and the league continues to establish itself as a major powerhouse of the women’s professional soccer league in the world.

Nadeshiko League Division 1 Teams

Image Credit:[b] , Direct Link

Format/Rules

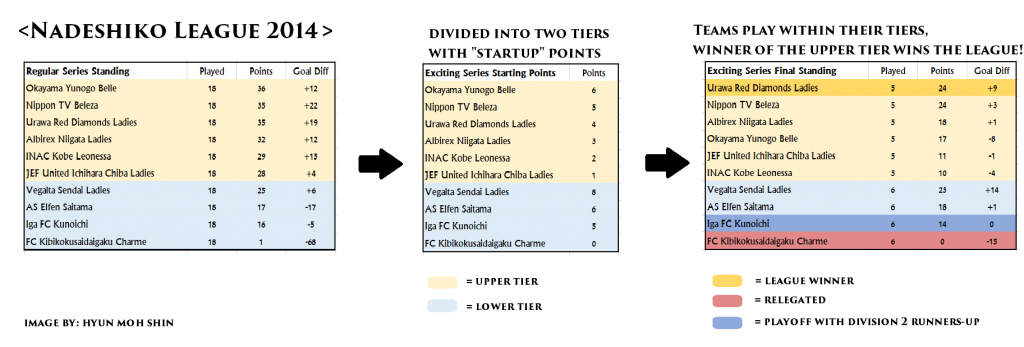

The L. League – especially its top division, the Nadeshiko League – has a format that definitely stands out amongst all professional soccer leagues. The league consists of two phases, the Regular Series and the Exciting Series[4]. In the Regular Series, the 10 Nadeshiko League teams follow a double round-robin structure – each team plays against all opponents within the division twice. From March to September, a total of 18 matches are played for each team, with the same point system as other soccer leagues: 3 for a win, 1 for a draw, and 0 for a loss. Based on the final league standing in the Regular Series, the league is divided into two tiers; the top 6 as upper tier, and the bottom 4 as the lower tier.

The Exciting Series then begins from October to mid-November within each of the two tiers – essentially a league tournament within each tier. Initially, each team is given a “starting point” depending on its final standings in the Regular Series. Lower-tier teams get 1/3, rounded, of the total points they earned in the Regular Series; Upper-tier teams get 7 points subtracted by their respective league standings. Then, the 6 upper tier teams undergo a single round-robin format (5 matches each) within their tier, while the remaining 4 in the lower tier undergo a double round-robin format (6 matches each). The points added from match results are in a same manner as the Regular Series.

The final standing from the Exciting Series becomes the final standing of the league, with the first in the lower tier counted as the 7th in the league. The bottom team of the league is relegated to the 2nd division, while the team second to the bottom engage in a two-round promotion playoff against the runners-up team of the 2nd division.

Such two-phase league structure is an unusual feature in professional soccer leagues, but it spices up the competition even further in two ways: firstly, it intensifies the mid-table competition in the Regular Series phase, and secondly, the within-tier competition allows more number of big matches to the crowd, with all teams in the upper tier having a good chance of winning the league. Unlike the mid-table teams in other leagues, who often lose tangible motivation to compete halfway through the season, those in the Nadeshiko League would want to end as top tier teams to truly avoid relegation scare, and therefore, the level of competition among the mid-table teams would be as fierce as that of the top and the bottom teams, up until the end of the Regular Series. Once the teams are include in the top tier, each of the top-tier teams have a decent chance of actually winning the cup, since the points deficit gets reduced in the start of the Exciting Series. The 2014 season was the prime example, which we will discuss later in the page.

Nadeshiko League Process in 2014

Image Credit: Self-Created

In terms of the player registration, there is currently no restriction on the total number of players that could be registered for the entire season; however, elementary students or of lower age cannot be registered to play. Up to 5 players from the reserves’ team can be registered to play; up to 5 foreign players can be registered, and up to 3 foreign players are allowed to play in each match.

The two lower divisions of the L. League, Nadeshiko League division 2 and the Challenge League, play in a more similar format as the major European leagues. The one major difference is that the two divisions follow a triple round robin format – that is, that every team faces the same opponent of the division three times. The Challenge League in particular acts more like a regional competition, similar to the Football Conference in England. Because of the league’s encouragement to incorporate as diverse a pool of female soccer players as possible, the Challenge League players are of a relatively more diverse age groups, from teens to early 20’s, while those in the two Nadeshiko League divisions consist mainly of college students and those with other professional occupations.

vs. Men’s J-League

Much like the difference between the women’s and men’s soccer league in other countries, the contrasting elements between the women’s L. League and the men’s J. League in Japan range from league format to financial structures. At the first glance, the most apparent difference between the two is the consistency in the league structure; J. League format has been fluctuating between a straightforward, double round robin format of the major European soccer leagues, and the two-phase format that the Nadeshiko League has consistently been using since 2005. Having switched to the double round robin format in 2004, the J. League decided to bring back the two-phase format starting from season 2015[5], in order to draw more crowd from more “big-match” opportunities that the format offers to the table. Specifics of such format in the Nadeshiko League is discussed above.

Another notable difference between the L. League and the J. League is the level of regulations required to create a team. Unlike the J. League, which have already been well established as a professional soccer league, the L. League regulations[6] require a less strict and more “interpretable” set of conditions that a soccer team must clear in order to receive league license from the JFA – essentially a permission from the JFA to participate in the league. In the financial eligibility category, for example, the J. League regulations[7]require the prospective club to be a formal corporate, founded under the Japanese law, and has at least a one-year management result. The L. League, on the other hand, simply requires “assurance” from the prospective clubs that they could financially last for at least a year.

As such, there is a huge difference in how the clubs are founded between the L. League and the J. League; while the J. League clubs are mostly founded as an incorporation through a specific set of business procedure, the L. League clubs are formed through various means[8]. Some, like Chiiba Ladies, are formed as a sub-group of an existing J. League club; some, like Jubiro Iwata Ladies, are formed by merging a number of small-group soccer teams. There even exists a club like Unai FC, formed through fitness center activities! These various origins of L. League teams stem from the fact that, relatively speaking, the L. League is still struggling to find talents and financial sources in order to build a club. This is also implied in a 2010 interview with Yukio Nakano, Managing Director of the J. League:

“Of course it is pretty much the same case for now, but back when the Japan Women’s Soccer League was called the L. League, it wasn’t a professional league but an amateur league; so there were a lot of teams with different backgrounds… now the league teams [have grown enough to] have players that are called up in the Nadeshiko Japan squad, but back then it was a tough time recruiting players.”[9]

Relationship to National Team

Because of such lack of sustainability amongst the L. League clubs, the L. League is greatly tied to the success of Japan women’s national team. The crisis period of the L. League from 2000 to 2004[3] are widely perceived to be triggered from the poor performance of the women’s national team around that period; specifically, its failure to qualify for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Conversely, the resent resurgence of popularity towards the L. League are widely attributed to the consecutive success in the national team since 2011 World Cup, in which they were deemed champions[10].

Similar to the relationship between the J. League and men’s national soccer team in Japan, the L.League serve as a common ground for the national team to be built around. Among the current Nadeshiko Japan squad, only 5 out of 24 players are playing in foreign leagues, and even the 5 foreign league players spent over 5 years in the Nadeshiko League, with an exception of Saki Kumagai, who spent 2 years in Urawa Red Diamonds before transferring to 1. FFC Frankfurt in 2011. As such, the sense of nationalism amongst the players are clearly present among the Nadeshiko Japan members. This is apparent in the team tactics of the current women’s national team coach, Norio Sasaki, or the appointment of the current captain, Aya Miyama, who has been playing in the Nadeshiko League for around 15 years over her entire career, and values team playing perfection over individual brilliance[11]. Details on the playing styles of the Japan women’s national team can be found in this page.

The Nadeshiko Japan As Winners of 2011 World Cup

Image Credit:[c] , Direct Link

Nevertheless, it is difficult to predict whether such close connection between the L. league and the women’s national team would persist in the future, if women’s soccer in general develops enough to have a more active transfer market activities than it is now. A good number of the current Nadeshiko Japan players have expressed through interviews that they would like to play in foreign leagues, preferably in the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL). The common reason shared by the players is that most of them have spent their youth career in the late 90s and the early 2000s – a crisis period of women’s soccer in Japan, and the golden age period of its United States counterpart. Kozue Ando, a current player in 1. FFC Frankfurt, echoes this desire in an interview with the Labo Magazine, Issue 424:

“When I first went to America as a national team member in 1999, which was the time when women’s soccer in Japan wasn’t popular at all. But America had tens of thousands of crowd pouring into the stadium. Those women soccer players were treated as star players, and that scenery was such an inspiring and longing one to me; it was the first time I thought ‘I want to play in the States!’ ” [12]

Of course, that is not to say that Japanese women soccer players including Miyama are resentful towards their professional league; on the contrary, the Nadeshiko League is seen as something to be proud of by many of them. They are simply desiring the same things that all soccer players commonly desire; somewhere their passion and hard work are more well-received and recognized than their current environment. As women’s soccer continues to grow, more opportunities to transfer to foreign leagues will be given to these players who set their career goal outside the Nadeshiko League. It will be interesting to see how the players will react by that particular era of women soccer. Would the Nadeshiko League surpass the foreign women’s soccer league so that the domestic players would feel loved and satisfied inside their league, or would there be a diaspora of Japanese women soccer talents to foreign land? Only time will tell.

Current Events

A new season of Nadeshiko League started in April[13]. Having finished in the first place in the Regular Series last season, only to slip up the lead in the Exciting Series to Urawa Red Diamonds Ladies, Okayama Yunogo Belle is desperate to make amends to its mistake. The club signed a whopping 11 players in this transfer period[14], but after three games with only one win, it seems that the new players would need time to bed into the squad. The Belles hope that their captain Aya Miyama, who also captains the Nadeshiko Japan, would show her leadership skills to form a strong team spirit between the old and the new. Meanwhile, INAC Kobe Leonssa has started the season spectacularly under a new coach, Takeo Matsuda. Having won all the first three games with 3 goals per game, the INAC is buzzing to build momentum on this perfect start.

Nadeshiko League 2015

Image Credit:[d], Direct Link

On the other side, Iga Kunoichi, who barely managed to avoid relegation through playoff last season, hired a new coach from South Korea, Jong Dal Kim, to help them gain stability in their squad[14]. With two wins out of three under their belt, the Ninjas would be eager to see some progression going on among their club. Other teams fighting against relegation, including the newly-promoted Speranza Osaka-Takatsuki, have also been active in player and coach recruitments; even though their start of this season is reminiscent of their poor start of the last season, the relegation-threatened clubs will continue to pursue for achievements beyond what they currently have.

These atmosphere of competition is universal among all professional soccer leagues; meaning that the L. League has potential to grow as much as its male counterparts. As we turn our head towards the Women’s World Cup this summer, it could be a lasting experience to observe the root of the Nadeshiko Japan, one of the strongest in the world of women’s soccer.

<References>

Note: Translations of all quotes and references done by Hyun Moh (John) Shin

[1] 日本女子サッカーの誕生 [Translate: The Birth of Japan Women’s Soccer], in Wikipedia(JPN). Retrieved April 14th, 2015, from http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A5%B3%E5%AD%90%E3%82%B5%E3%83%83%E3%82%AB%E3%83%BC#.E6.97.A5.E6.9C.AC.E5.A5.B3.E5.AD.90.E3.82.B5.E3.83.83.E3.82.AB.E3.83.BC.E3.81.AE.E8.AA.95.E7.94.9F

[2] 皇后杯全日本女子サッカー選手権大会 [Translate: Empress’ Cup], in Wikipedia(JPN). Retrieved April 14th, 2015, from http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%9A%87%E5%90%8E%E6%9D%AF%E5%85%A8%E6%97%A5%E6%9C%AC%E5%A5%B3%E5%AD%90%E3%82%B5%E3%83%83%E3%82%AB%E3%83%BC%E9%81%B8%E6%89%8B%E6%A8%A9%E5%A4%A7%E4%BC%9A

[3]美しく勝利せよ・女子サッカー[Translate: Win Gracefully, Women’s Soccer], Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Homemate Research, 2011.

[4]リーグ概要[Translate: League Biography], Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Japan Women’s Football League, 2015

[5] J-League to Adopt Two-Stage Format, Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Japan Times, September 11th, 2013

[6] なでしこリーグ準加盟申請承認について [Translate: About Nadeshiko League Associate Membership Application Approval], Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Japan Women’s Football League, 2015.

[7] 第3章 所属団体 [Translate: Chapter 3, Member Groups], JFA Rules and Reguations, Web, Retrieved Arpil 14th, 2015, Japan Football Association, 2015.

[8] 女子チームのつくりかた[Translate: How Women Teams Are Created], Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015. Japan Football Association, 2015

[9] Jリーグ 中野幸夫専務理事 インタビュー[Translate: J League Managing Director Yukio Nakano Interview], Web, Retreived April 15th, 2015, Japan Football Association, 2011. http://www.jfa.or.jp/nadeshiko_vision/tsukurikata/modelcase/i_01.html

[10] Ryo Utsumi, Women’s game enjoys newfound popularity but not counting its laurels, Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015. Asahi Shinbun, April 3rd, 2012

[11] 【なでしこジャパン】宮間あやインタビュー「イニエスタやシャビを見習いたい」[Translate: [Nadeshiko Japan] Interview With Aya Miyama “I want to learn from Iniesta or Xavi”], Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Web Sportiva, November 5th, 2011

[12] ラボーインタビュー23、梢安藤さん[Translate: Labo Interview 23, Ms. Kozue Ando], Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Labo Magazine, Issue 424, May 2014.

[13] Ken Suzuki, Player transfers in and out of Japan 2015, Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Womens Soccer United.com, Janurary 8th, 2015.

[14] Nadeshiko League Division Standings, Web, Retrieved April 14th, 2015, Full Bloom Guidebook, April 12th, 2015.

<Image Credits>

[a] 元日に笑うのは浦和か、ベレーザか 第36回皇后杯全日本女子サッカー選手権大会. N.d. Photograph, Japan Football Association, December 31st, 2014.

[b] Nadeshiko League 2014: Nuevo formato, más igualdad. N.d. Photograph, Protagonistas del Juego, April 14th, 2014

[c] KYODO, Jun Hongo, Nadeshiko Japan eyes London Olympic gold, N.d. Photograph, Japan Times, Janurary 24th, 2012

[d] Asa, INAC Kobe Leonessa lead the Nadeshiko League, N.d. Photograph, Women’s Soccer United.com, April 12th, 2012

Hello to every one, the contents present at this website are genuinely remarkable for people experience, well, keep up the good work fellows.

Always very interesting to see countries with inconsistent men’s soccer teams do well in women’s soccer. I think the Japanese team being 4th in the world can be shown as an evidence to the fact that a country doesn’t necessarily need a soccer culture to be successful in women’s soccer. USA can be shown as an example to this situation as well.

This is all very well done, John! One small thing you could do in addition to the image credits in the notes is to make is so that when you click on the image it goes to the original url where it came from, rather than just to the same image but larger. Also (& I’m suggesting this for the group as a whole), you’ll want to include some navigation links from within the page so people can go back to the main page easily.