By Faith Haberer

John Calvin was born in 1509 in the French town of Noyon. His father sent him to study theology at a university in Paris, but later changed his mind and wanted Calvin to become a lawyer. His education in law rather than orthodox theology allowed him to be exposed to the writings of Erasmus and to study the Bible without a solely Catholic orthodox framework. During this time, he learned the “three languages of Ancient Christian discourse”: Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. After this a French Reformer convinced Calvin to settle in Geneva to help plant religious reform.

When thinking about theology, Calvin labelled it into essentially two thought processes: knowledge of God’s nature and knowledge of human nature. His understanding that God is good and perfect and that humans are sinful and need grace are important context to understand before looking deeper into any of his beliefs. He also believed that knowing the character of God is important to glorify him because it affects how people interact during their everyday lives.

Calvin’s theology notably placed an emphasis on predestination for salvation in his writings. In Institutes of the Christian Religion, he references Romans 11:6 where Paul discusses that the “election of grace” is by grace alone and not works. Calvin believes this to mean that salvation comes only by God’s mercy. He also takes it to a deeper level that God predestines or determines in advance who goes to heaven. Calvin discusses that this idea is obvious because of unequal access to information and here, specifically the Gospel. Many would take this to mean that heaven is only offered to some people, but Calvin already addresses it by describing God’s perfect wisdom.

John Calvin also advocated for women’s involvement in church and specifically the role of female deacons who were to take care of the poor. He questioned purely literal interpretations of Paul’s letters that denied women all involvement in speaking at church, and instead he advocated that there were some occasions that women were needed to speak. Some examples of women who participated in the Reformation by speaking out are Margaret Fell and Argula von Grumbach.

Sources

Bouwsma, William J. “Explaining John Calvin.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 13, no. 1 (1989): 68-75. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.guilford.edu/stable/40257444.

Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Translated by Henry Beveridge. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classic Ethereal Library, 1536.

Douglass, Jane Dempsey. “Christian Freedom: What Calvin Learned at the School of Women.” Church History 53, no. 2 (1984): 155-73. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.guilford.edu/stable/3165353.

Hillebrand, Hans J. The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. Oxford University Press. (1996). doi: 10.1093/acref/9780195064933.001.0001

Ottati, Douglas F. “Reformed Theology, Revelation, and Particularity: John Calvin and H. Richard Niebuhr.” Cross Currents 59, no. 2 (June 2009): 127-143. Humanities International Complete, EBSCOhost.

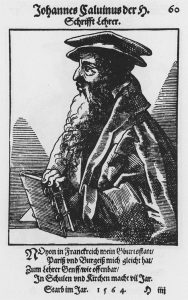

Tobias Stemmer. John Calvin 1564. Book Ilustration, 101 x 80 mm. The Illustrated Bartsch. Vol. 19, pt. 2, German Masters of the Sixteenth Century. Available from http://library.artstor.org/#/asset/BARTSCH_2890010.

Sudduth, Michael L. Czapkay. “The Prospects for ‘Mediate’ Natural Theology in John Calvin.” Religious Studies 31, no. 1 (1995): 53-68. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.guilford.edu/stable/20019715

Last edited 12/07/17

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.