Rena Bartos, The Woman’s Market Expert

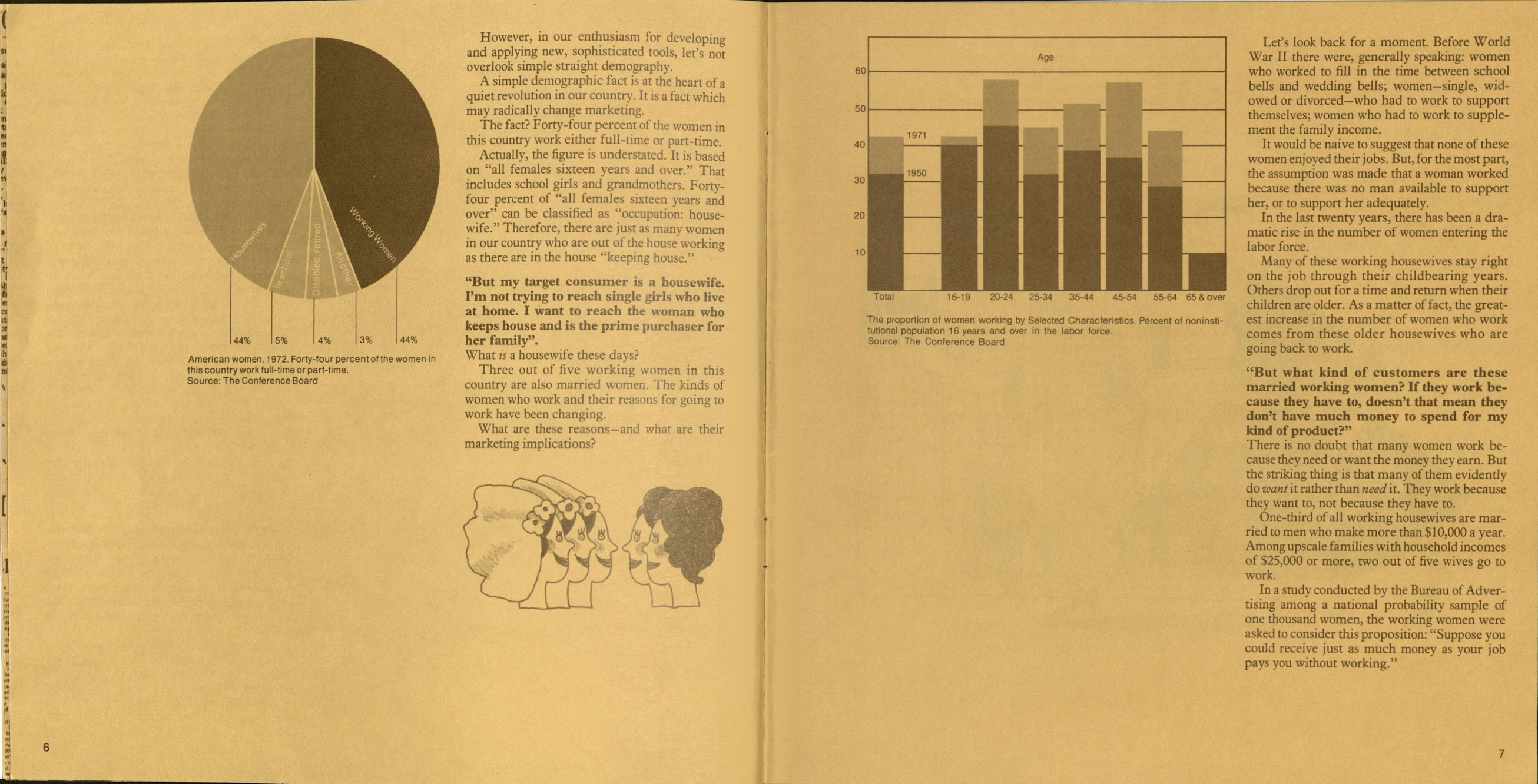

Rena Bartos was an advertising market researcher, executive, and consultant from 1960 to 1998. In her role as senior vice president and director of communications development at J. Walter Thompson Company, she became recognized as an expert in marketing and advertising towards women. She was a trained sociologist who identified shifting societal and cultural trends and their application in advertising. In the early 1970s, as the women’s liberation movement gained traction, Bartos took notice of the growing number of women in the workforce and changing attitudes about the role of women in society. She dubbed this change in demographics and public sentiment, “The Quiet Revolution.” While some experts look back on this change as “the single most outstanding phenomenon of our century,” most advertisements in the early 70s continued to depict women as 1950s housewives and sex objects.

“The dramatic rise in the number of working women in the United States is the single most outstanding phenomenon of our century.” -Eli Ginsburg, chairman of the National Commission of Man-Power Policy

Bartos, along with a few other female advertising executives, were some of the first to recognize the lack of representation of working women and women in non-traditional roles in advertisements. She believed that the underlying assumptions on which the woman’s market was based were out of step with the realities of the time. Thus she dedicated her research to understanding the changes in women’s lifestyles and values. Although Bartos was careful to never self-identify as a feminist, she was a practical marketer. She recognized that “Outmoded assumptions about women…lead to marketing underachievement,” and knew that the key to tapping into the lucrative women’s market was to understand it (What Every Marketer Should Know About Women, 1978). In 1973, she piloted the “Special Markets Project” at J. Walter Thompson in order to understand the mid-20th-century woman consumer. She collected data on the attitudes, personal values, media behavior, and buying style of women in the US and around the world. This preliminary research was the foundation of her series of influential pamphlets and book on advertising to women, The Moving Target. Check out a preview of the pamphlet below:

Rena Bartos Papers 1962-1998, box 13

“New Demographics”: The Many Faces of the Women’s Market

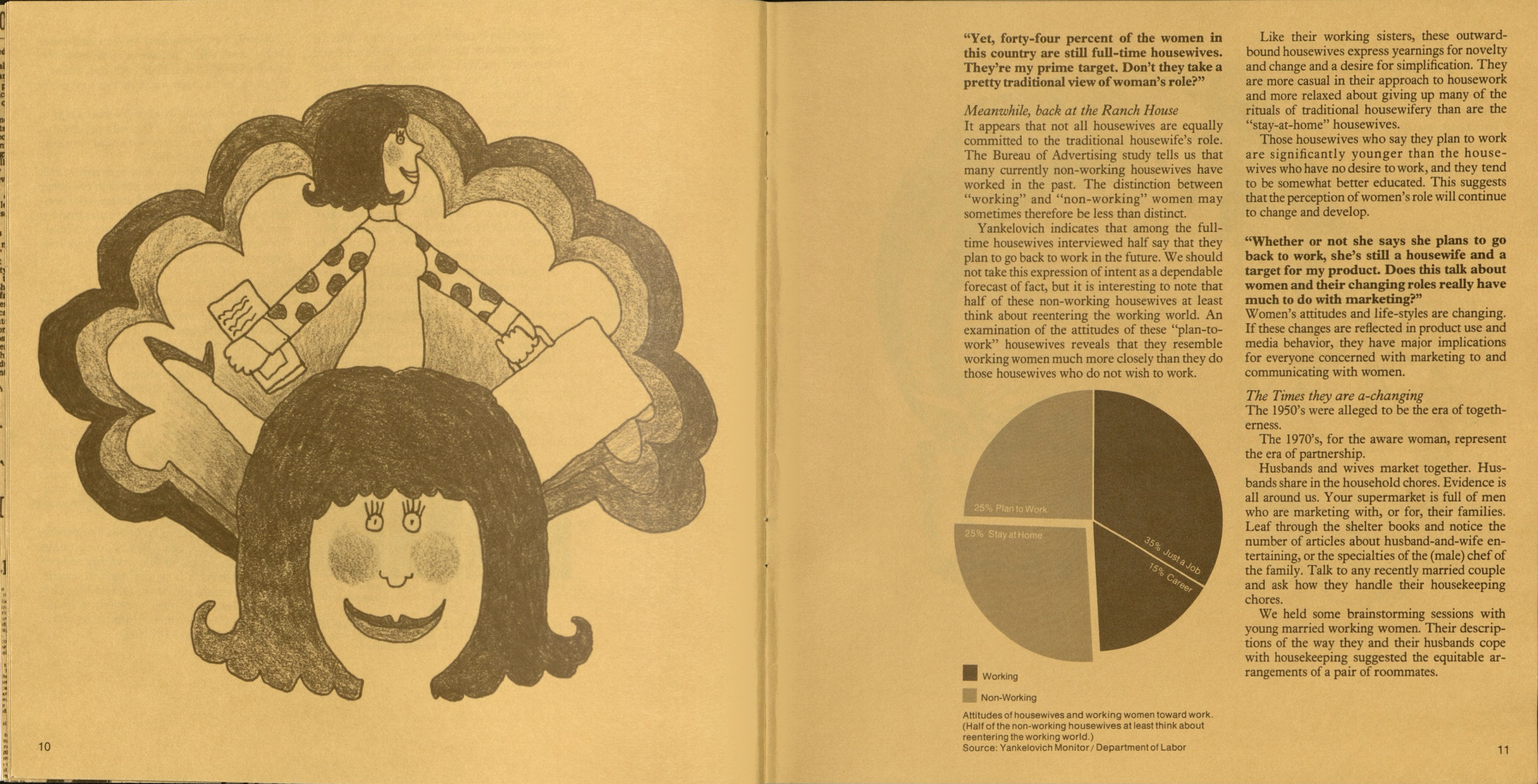

Bartos’s thorough research revealed that the woman’s market could be divided into distinct groups based on lifestyle, values, motivations, media use habits, and purchasing behavior. Her “new demographic” groups, which included career women, “just-a-job” working women, “plan-to-work” housewives, and traditional housewives challenged the conventional advertising wisdom that all working women or housewives were the same. The profiles of each of these “new demographic” groups are summarized as follows:

The Career Woman:

While only representing around 15% of women, by nature of her high level of education, style-consciousness, and disposable income, the career woman represented the target consumer for personal grooming, travel, financial services and automobile product categories. The career woman was motivated by personal achievement and fulfillment and identified as self-confident, broad-minded, efficient, and independent. She was the heaviest consumer of magazines and newspapers, and listened to the radio the most frequently. When shopping, the career woman tended to plan ahead, purchase with caution, and be brand-loyal–although she admitted to occasionally buying on impulse.

The “Just-a-Job” Working Woman:

This second category of working women made up 35% of the women’s market. While they maintained either part or full-time occupations outside of the household, their motivations for working differed from the career women. The “just-a-job” woman reported working out of economic necessity or to add interest or a sense of independence to her life. On the whole, this group had lower levels of educational attainment and affluence and in terms of her self-image and mindset, this group tended to have more in common with the traditional housewife group, with more traditional-leaning views and lower self-image than the career woman. The “just-a-job” working woman was not particularly loyal to brand names. Rather, she was an “experimental” shopper likely to try new products and brands.

The “Plan-to-Work” Housewife:

Advertisers had neglected a subset of women who planned to return to the workforce after about ten years as housewives. In fact, these ‘plan-to-work’ housewives accounted for 25% of the women’s market. Surprisingly, this demographic had more in common with the career woman in terms of educational attainment and self-perception than they did with traditional housewives. As the youngest group, “plan-to-work” housewives represented a new generation of affluent, well-educated, and open-minded women who viewed being a housewife as a transitional period, rather than a never-ending and all-consuming occupation. This group was the most active consumer of media and consumer products.

The Traditional Homemaker:

The traditional homemaker represented 25% of the women’s market. This demographic most closely reflected the traditional housewife commonly portrayed in advertisements at the time. She had the lowest level of education and perceived herself as kind, refined, and reserved–but not brave or dominating. This group prioritized economy when shopping and did not engage in impulse buying. Surprisingly, traditional homemakers spent less on cleaning products like floor polish and rug shampoo than both career women and “plan-to-work” housewives.

Implications for Advertisers:

The characteristic of these “new demographic” groups had important implications for advertisers. American women were a more diverse and dynamic group than advertisers had apprehended. In particular, the discovery of the “plan-to-work” housewife demographic challenged advertisers’ preconceived notions about the lifestyles and values of American housewives. Advertisers using outdated depictions of women, not only risked alienating working women, but also 50% of housewives, who had more in common with career women than the stereotypical homemaker.

“The real marketing implications of the changing role of women is that the woman’s market really is a moving target and both working women and housewives are more than one kind of target.” -Rena Bartos, 1982

Moreover, an internal survey conducted by Rena Bartos at JWT on the attitudes of the “new demographic” groups towards depictions of women in advertising found that while the groups’ lifestyles and ideologies differed, overall they preferred ads that depicted women in “contemporary” and diverse roles, over ads that showed women in traditional roles. Bartos explained that while surprising, the results of the survey showed, “that women in traditional lifestyles really endorse the new values.” (Report of a Study Conducted on the Image of Women in Advertising, 1976) The two pages from the report below show how the researchers measured the subjects’ responses to the commercials.