New Products Proposed for Feminists

While those identifying as members of the women’s liberationist movement were relatively small in number, some advertisers believed that feminism’s broader influence on the attitudes and lifestyles of American women merited their attention. As early as 1970, several industry experts predicted that the movement would create a completely new set of consumer needs that would require distinct marketing plans. Out of a demand for broader sharing of family responsibility, they predicted an explosion in the convenience goods and services market. These advertisers believed that home cleaning services, cafeterias in apartment and housing complexes, and fast food were among the many goods and services that would appeal to the “liberated woman”. They saw the liberationists’ demands for sexual equality and their disdain for the sexual objectification of women as an opportunity for a whole new category of gender-neutral boutiques to sell the dungarees and capes preferred by leaders of the movement. Advertisers predicted that because liberationists promoted self-improvement through education and culture, women would re-locate to urban centers where they had access to museums and libraries. This urban shift would create a demand for department stores in urban centers. Detail oriented advertisers even saw an opportunity in markets for Women’s Studies textbooks coming out of the movement.

Despite discussion of creating products and marketing strategies targeted to feminists, these new market opportunities largely went ignored by advertisers in practice–much to the dismay of several proponents of this shift. Tina Santi of Colgate Palmolive lamented that “when 30,000,000 women began to wear pants to the office,” women’s clothing manufacturers “didn’t take advantage.” Instead, they left men’s clothing manufacturers to capture this market. (The New Woman is Here,1979)

Co-opting Feminist Symbolism

For the most part, the women’s liberation movement served as creative fodder for copywriters. Advertisers co-opted symbols and language from the movement to mass-market everything from douches to lingerie (which ironically, were decidedly un-feminist products). Copywriter Caroline Bien, whose contributions to the advertising industry are described in more detail on the interview page, acknowledged that co-opting feminist language was common industry practice in the early 70s–and one that was unavoidable. Upon reflection, she said, “I think you had to use the language; the whole point of advertising is that you sense what’s out there and you take it.” At the time she “[doesn’t] think [she] felt guilty,” rather she “thought [she] was using appropriate language for the time.” At the end of the day, she says of advertisers, “you’re selling things; you’re selling ideas.”

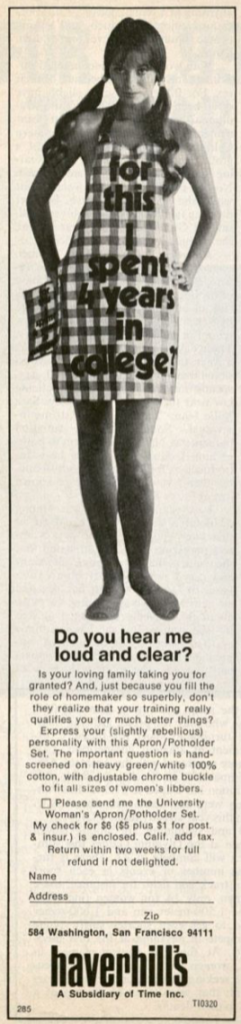

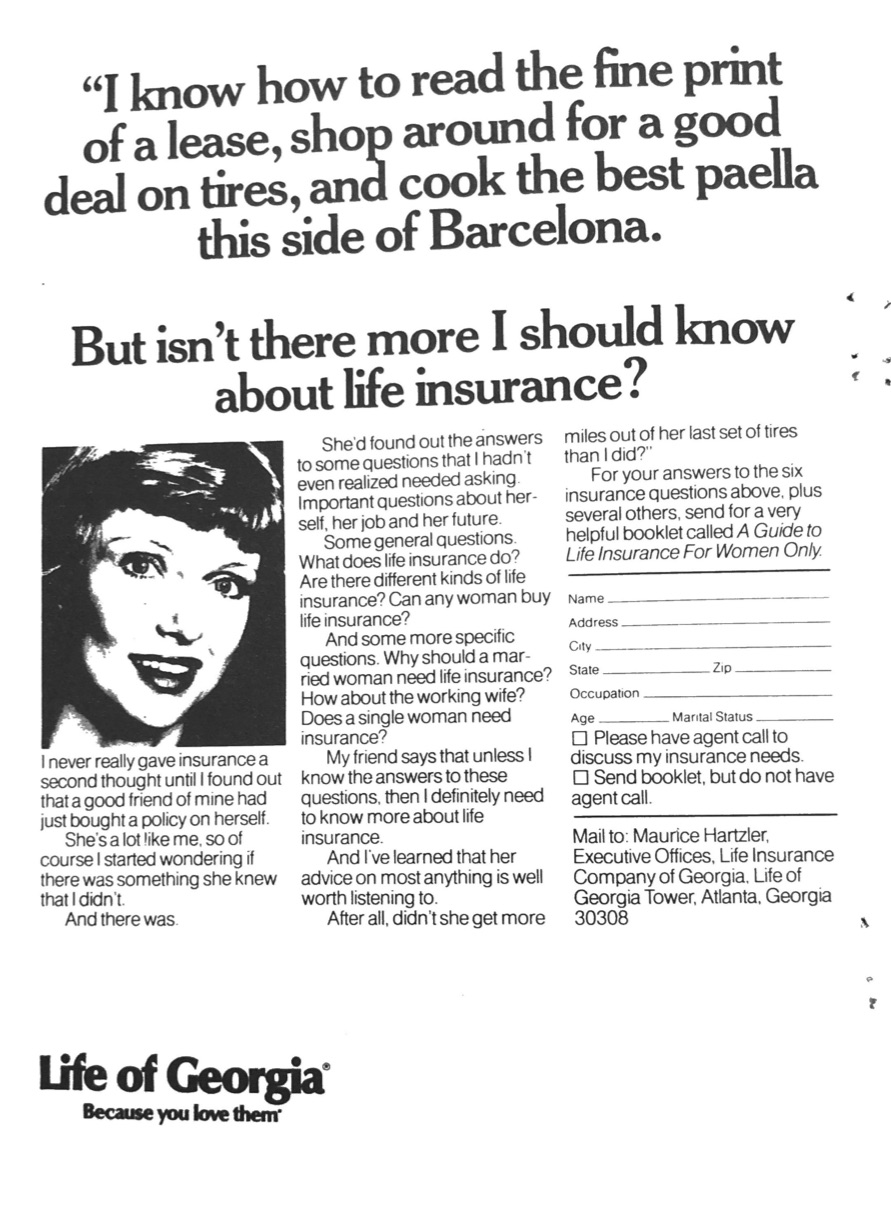

Print ads targeting feminists from 1977 copy of NOW newsletter, AlFA archives, Box 8, NOW – Atlanta Chapter 8.19

Women’s Liberationists Demand New Ads

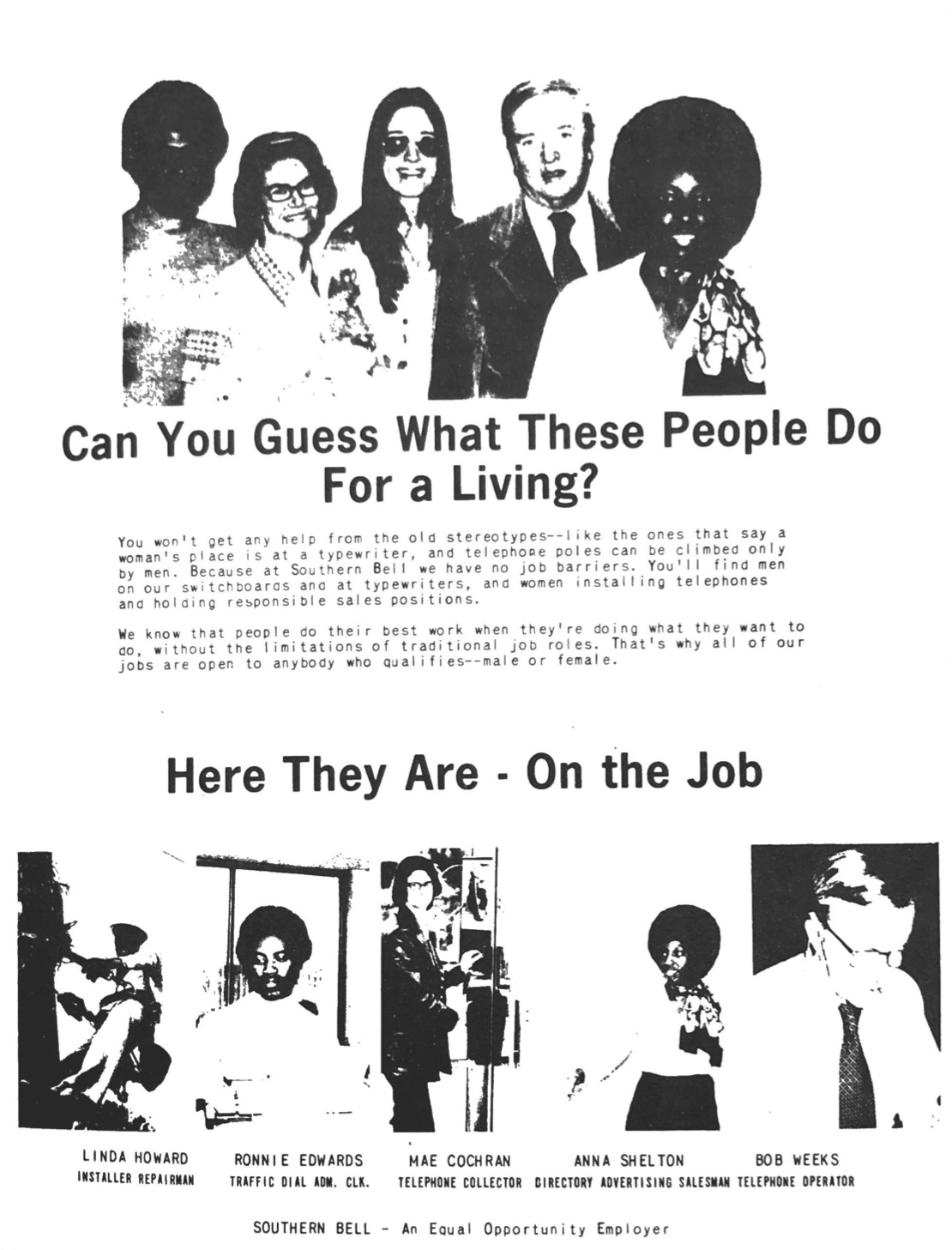

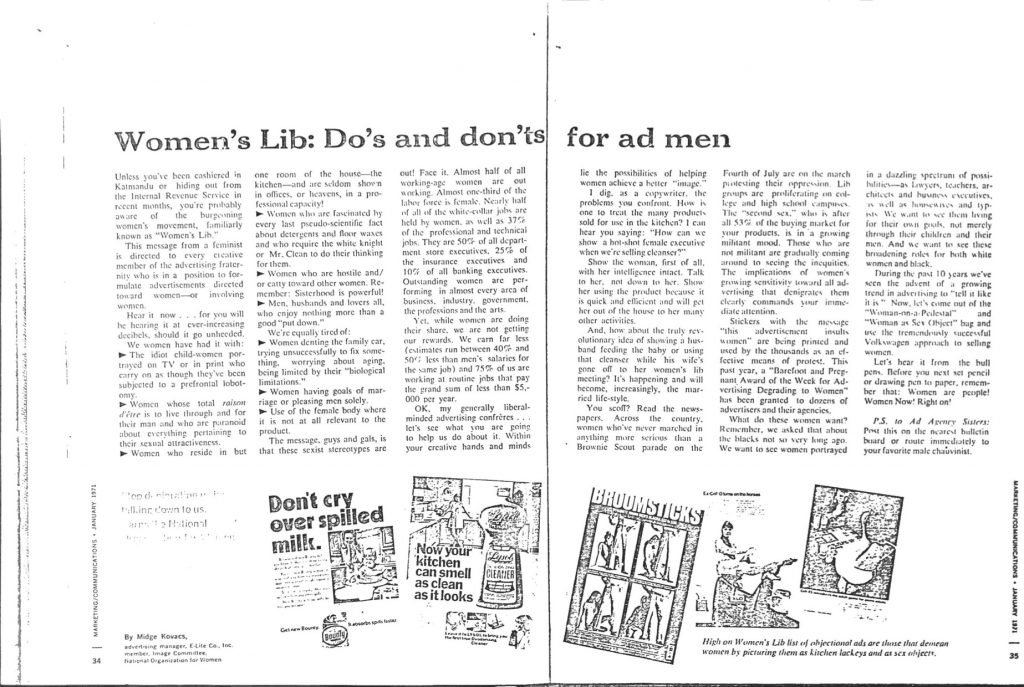

Feminist critics of advertising did not want new products, they wanted advertisers to abandon degrading sexist stereotypes. Instead of the portrayal of women as idiotic, cleaning-obsessed, sex objects, they demanded at the very minimum, the portrayal of competent women in the full variety of roles they played or better yet, “the truly revolutionary idea of showing a husband feeding a baby.” As one means of protest, feminists printed thousands of stickers with the message “this advertisement insults women.” Liberal feminists, who acknowledged advertising was not going away, appealed to their “ad agency sisters” to speak out against the sexist treatment of women in advertisements. In the following flier distributed by the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1971, members encouraged female advertising professionals to “post this immediately on the nearest bulletin board or route immediately your favorite male chauvinist.”