Images: Ladies’ Home Journal, Box 87.1. Roy Lightner Collection of Antique Advertisements, Box 5. ProQuest Essence Magazine, Volumes 1 & 2. Ad*Access. D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles, Box 112. Jean Kilbourne Papers, Boxes 77 & 79.

Before the Internet took off in the late 1980s, much of the external social pressures that displayed how one’s life “should” look came from print advertisements.

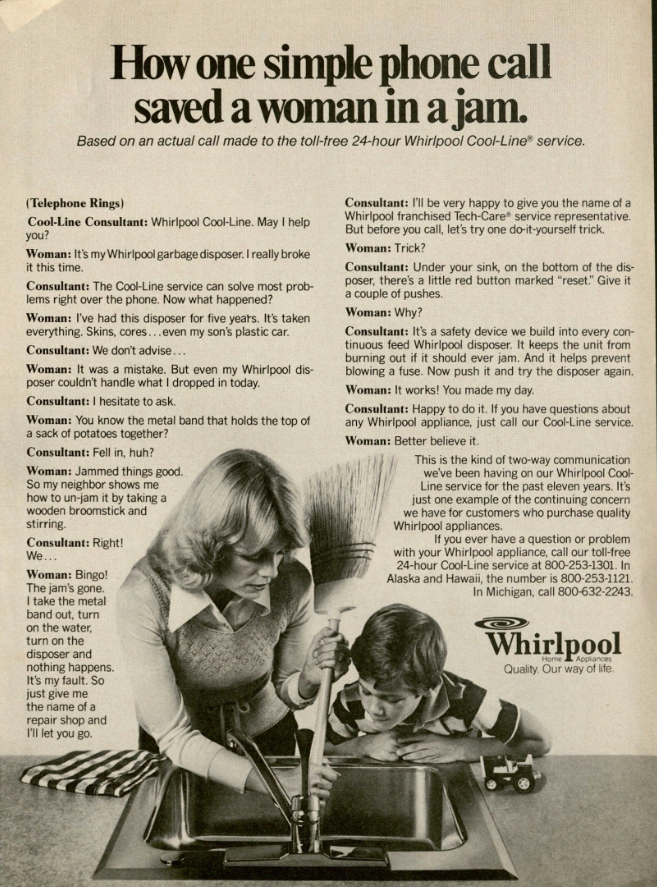

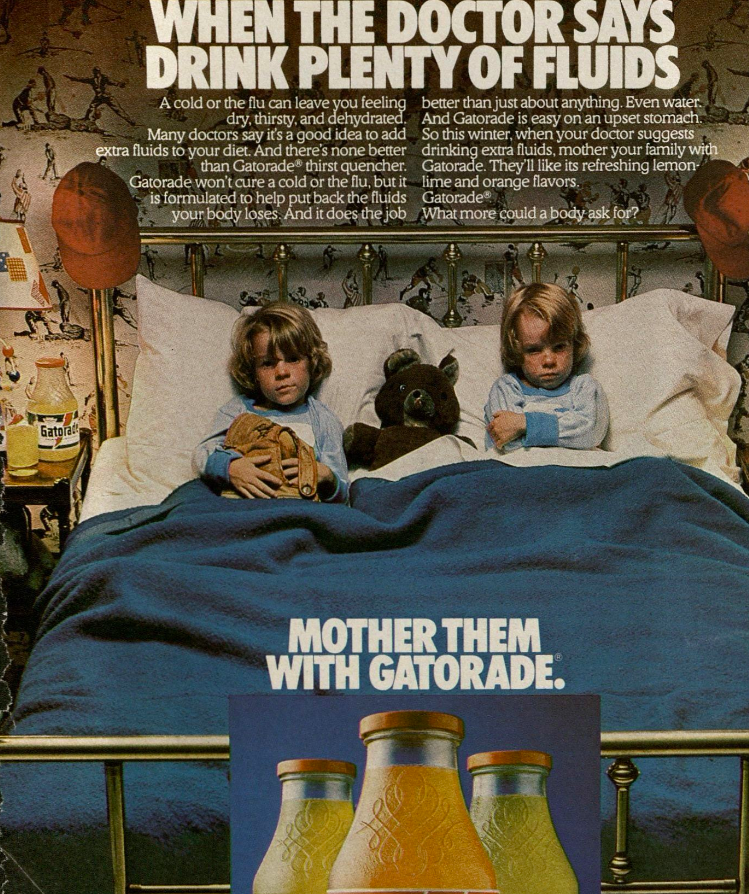

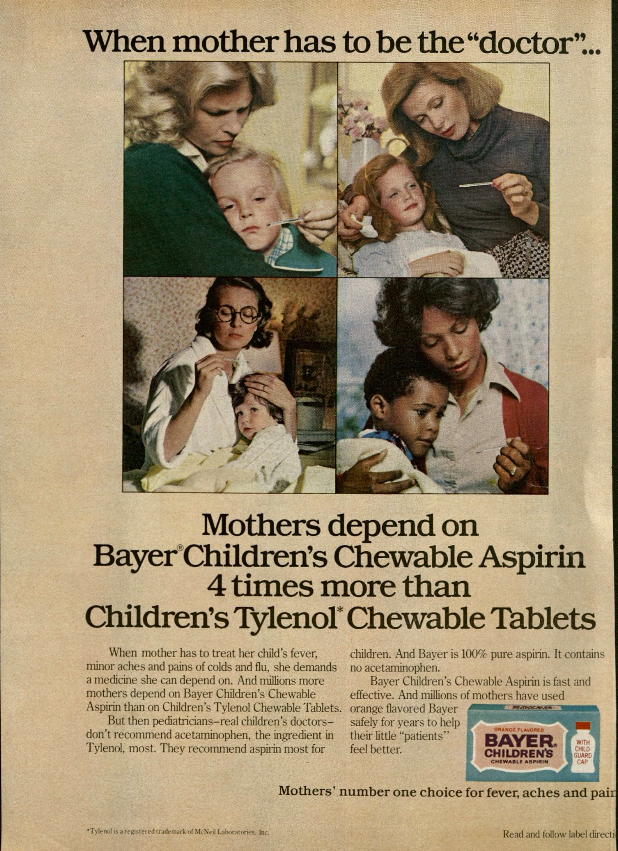

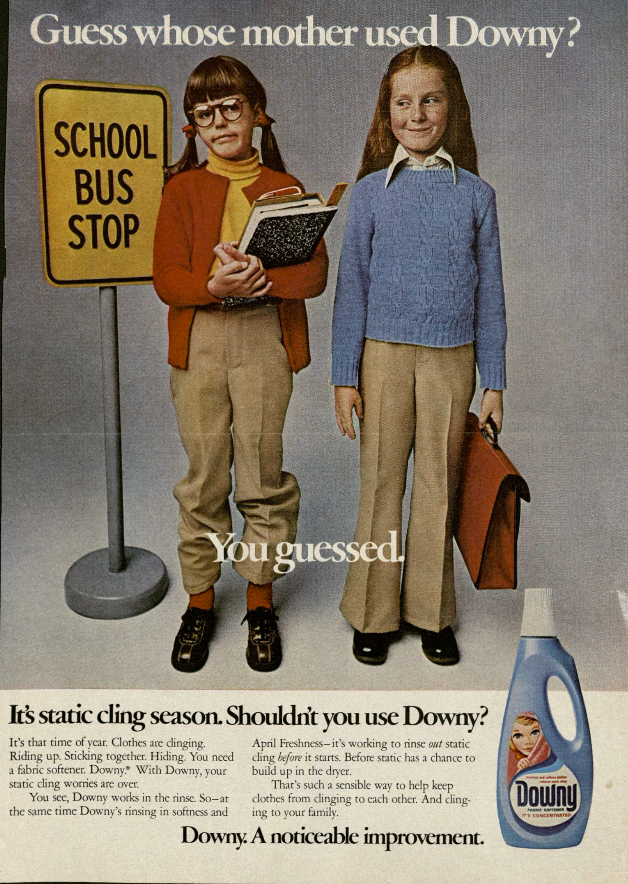

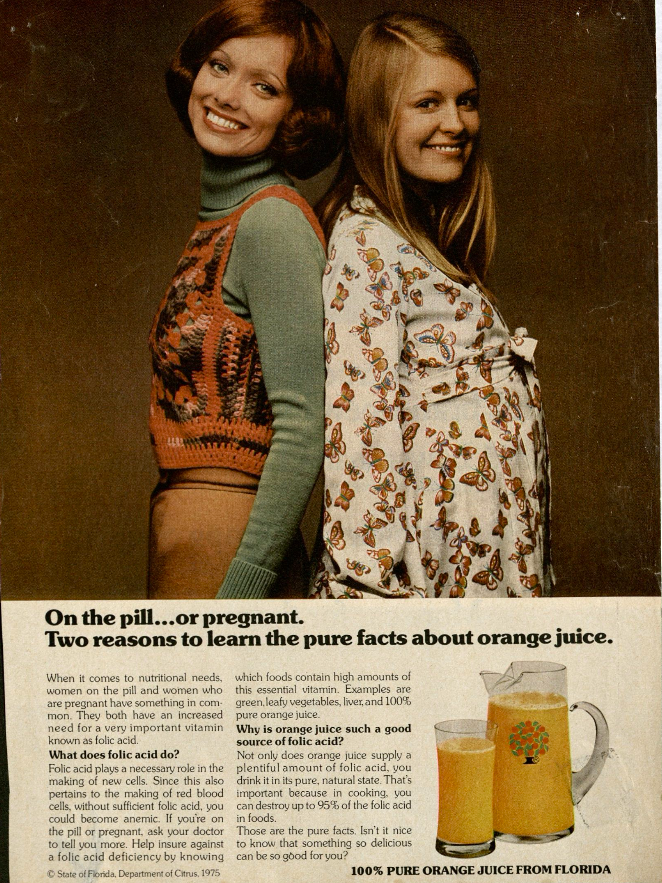

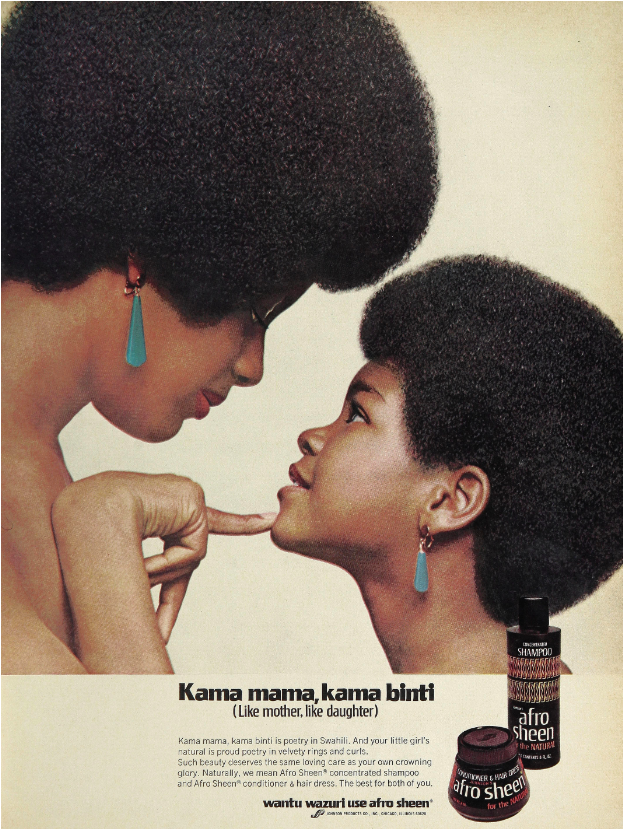

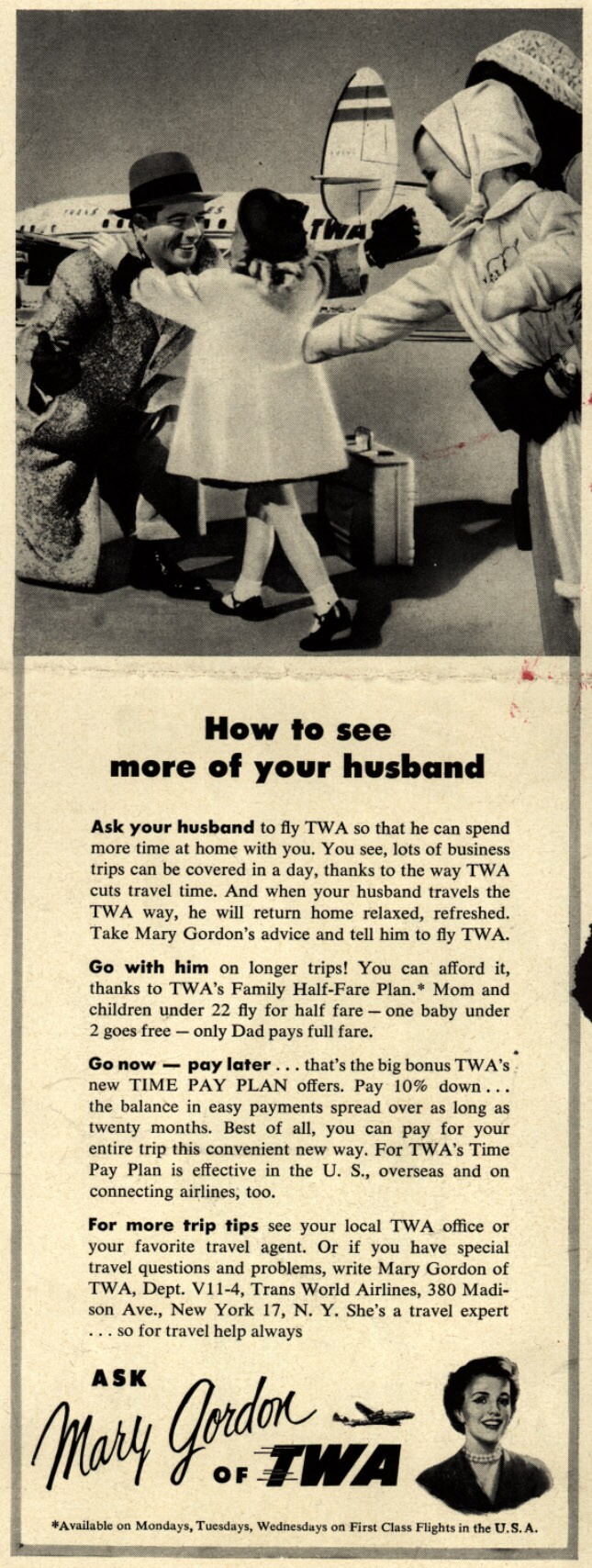

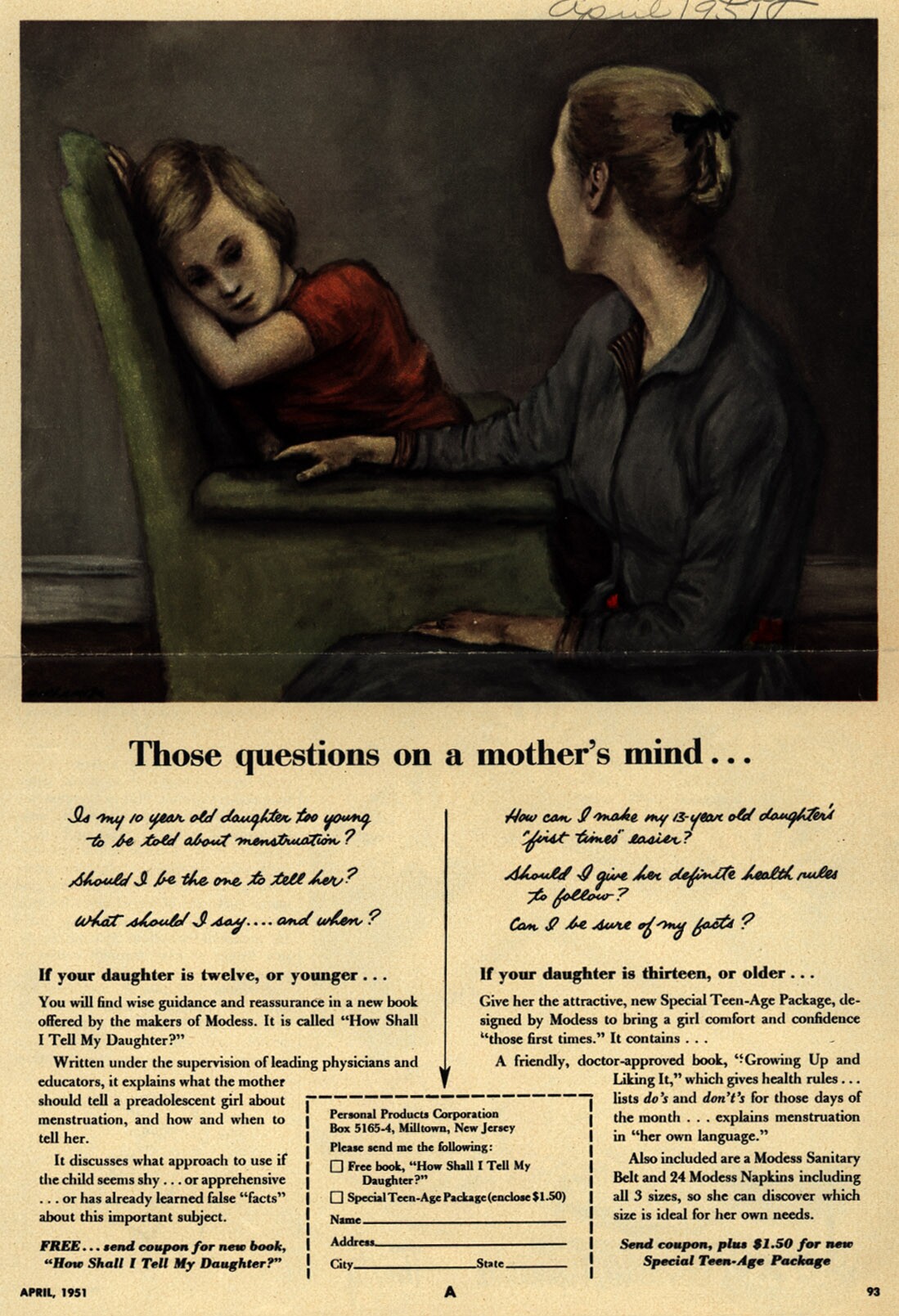

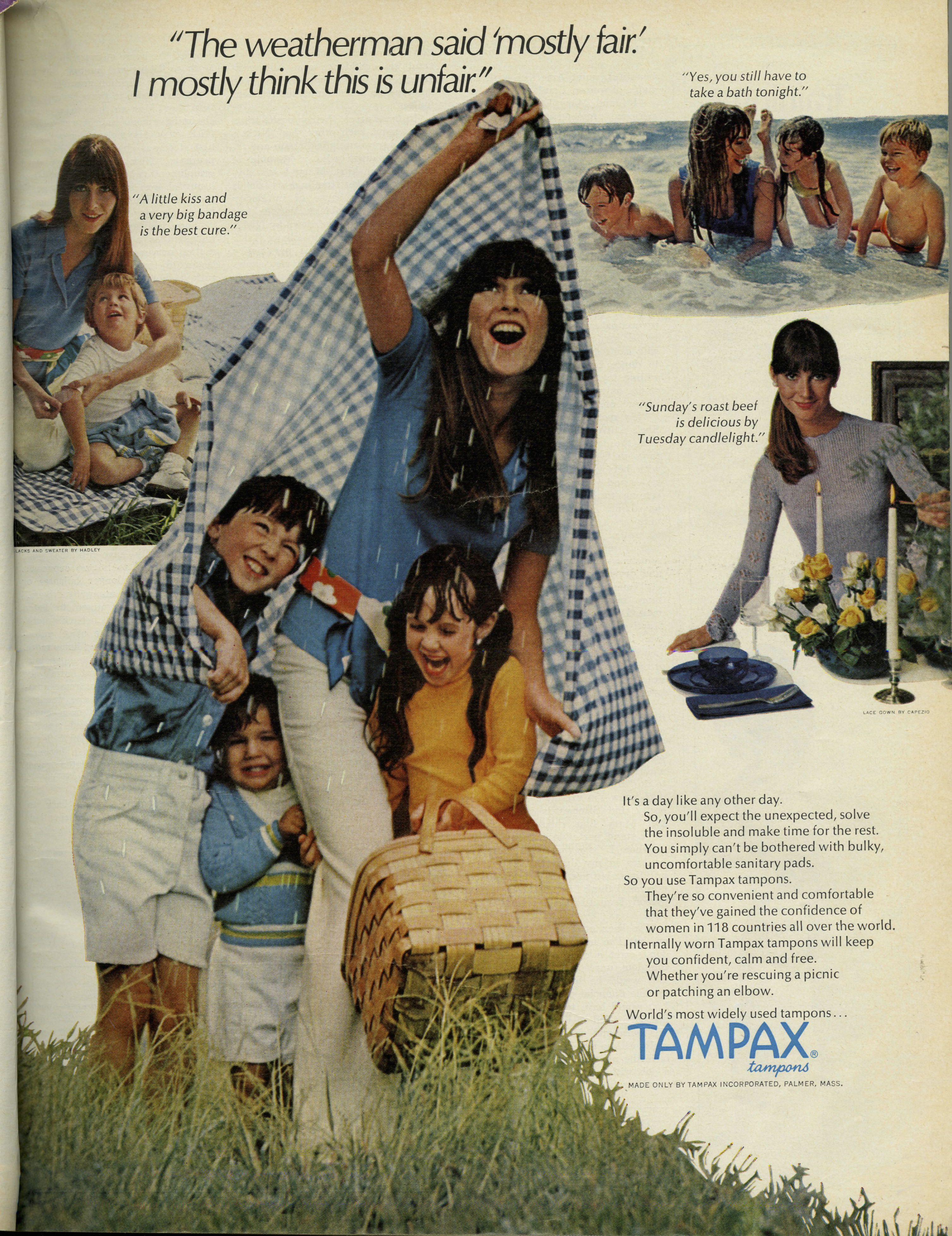

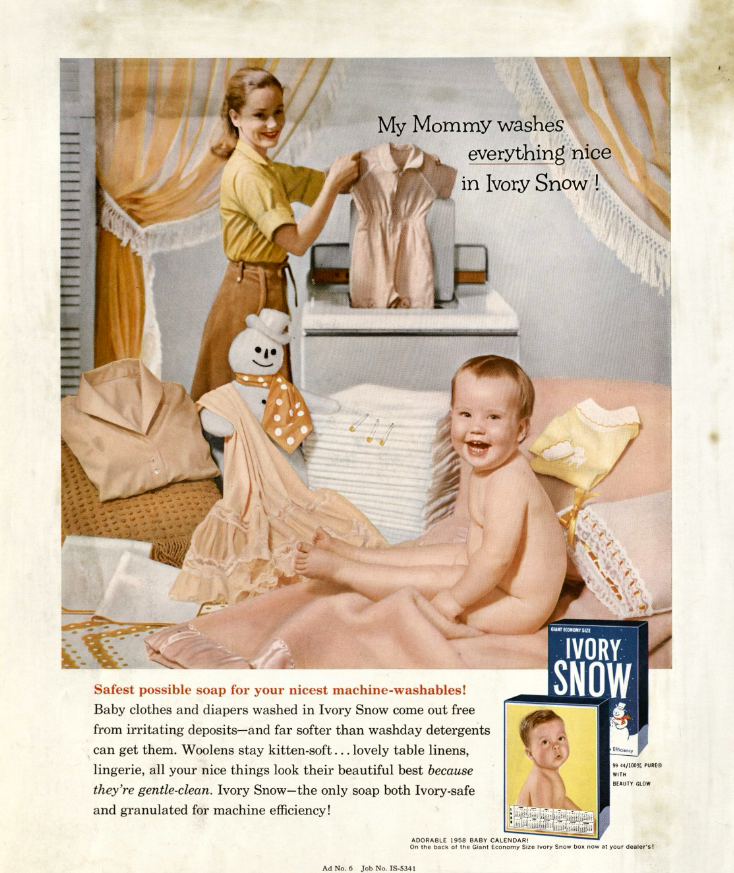

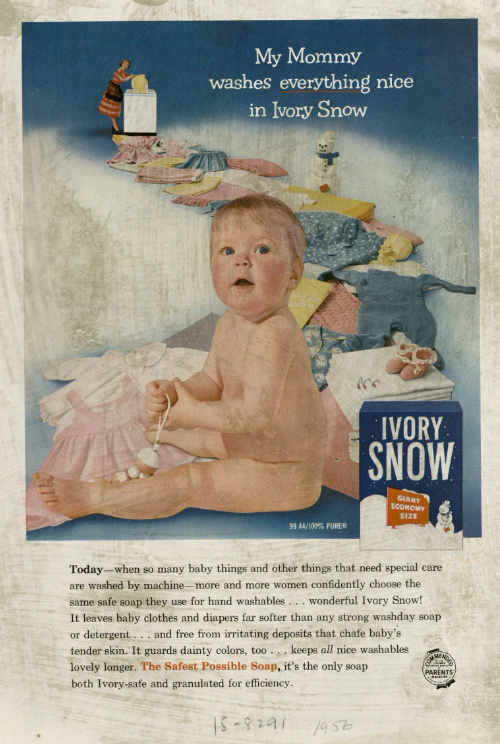

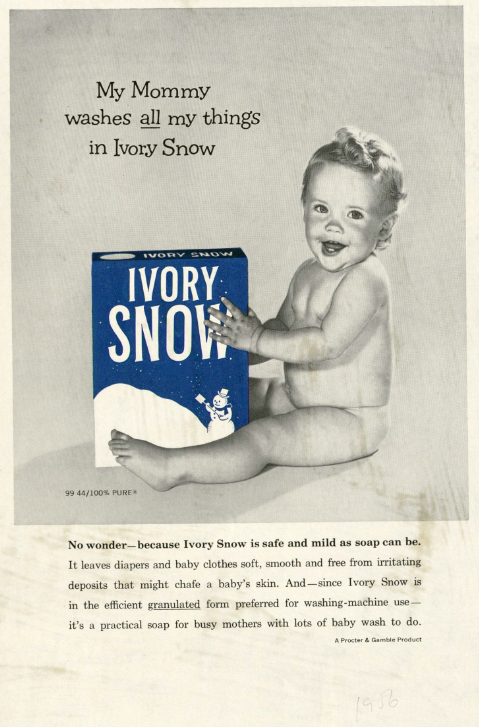

Whether agencies were advertising cleaning supplies, kitchenware, toys, or feminine products, they recognized the importance of showcasing women in ads. Depicting women was important because not only were women doing the majority of the housekeeping, cooking, and childcare, but they were also the main consumer base.

Agencies needed to show women in their ads, but the way they chose to do so was (and still is) harmful to the advancement of women and the movement towards gender equality. Showing women as housekeepers, wives, and mothers was detrimental because it limited what women were supposed to do, what they were supposed to look like, how they were supposed to act, etc.

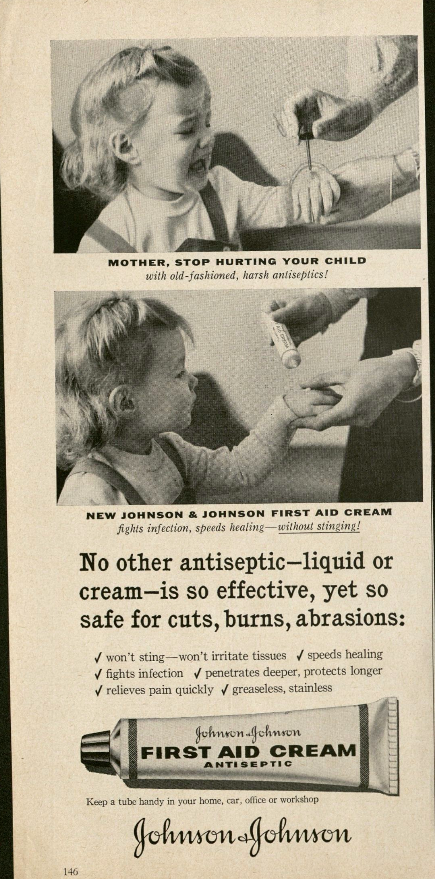

In the advertisements above, one can see a mother with her children and husband that says “they need me” and a woman holding a baby with the tagline “because you’re a woman” not “because you’re a mother,” implying that womanhood requires having children. Mothers are shown or described taking care of sick children, fixing their children’s injuries, doing their children’s laundry, clothing their children, singing their children to sleep, cleaning their children, changing their children’s diapers, comforting their children, playing with their children, etc. All actions that could be done by either parent, but would never have been shown with a father in that time. This abundance of advertisements made it seem as if families could not function without mothers doing absolutely everything, putting pressure on women not only to have children, but to raise those children alone.

In 1982, researchers Paula England and Teresa Gardner evaluated the presentation of men and women in magazine ads and found that women were almost twice as likely to be portrayed parenting and 22 times more likely to be shown doing housework or cooking. Men, on the other hand, were over five times more likely to be shown occupationally (How Advertisers Portray Men and Women, 1982).

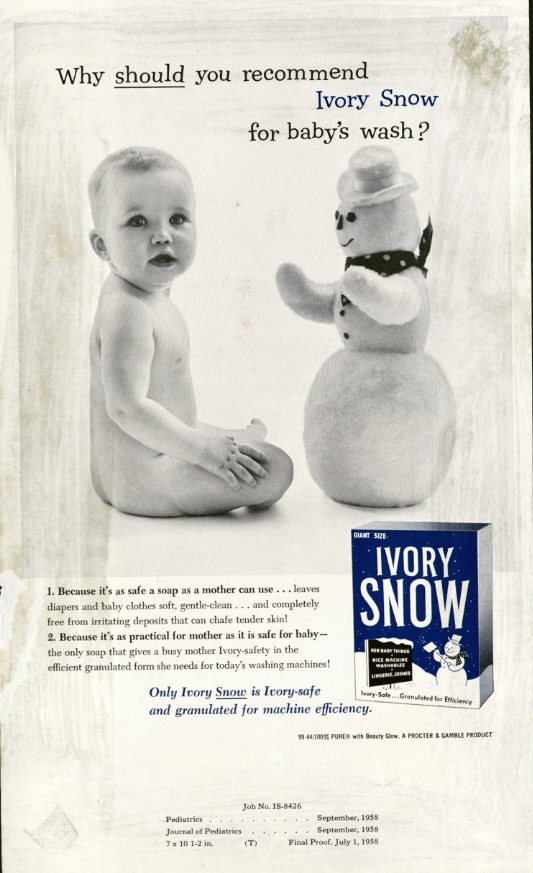

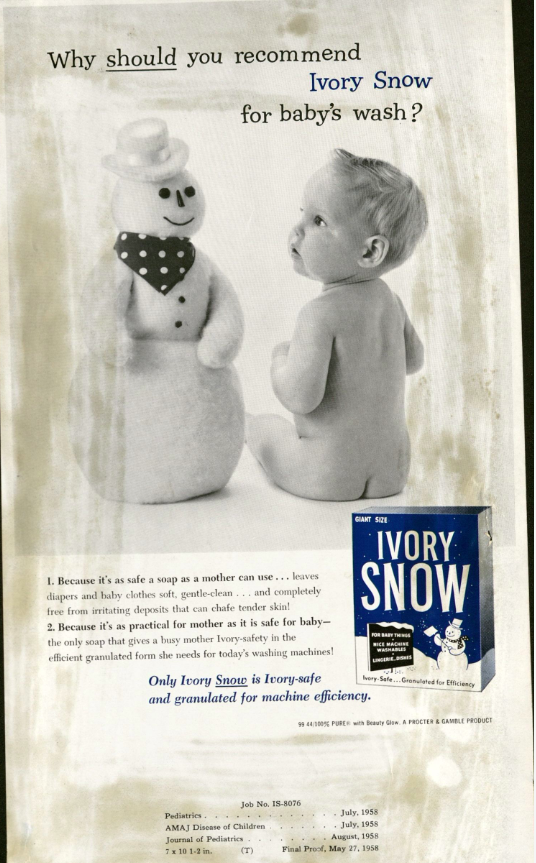

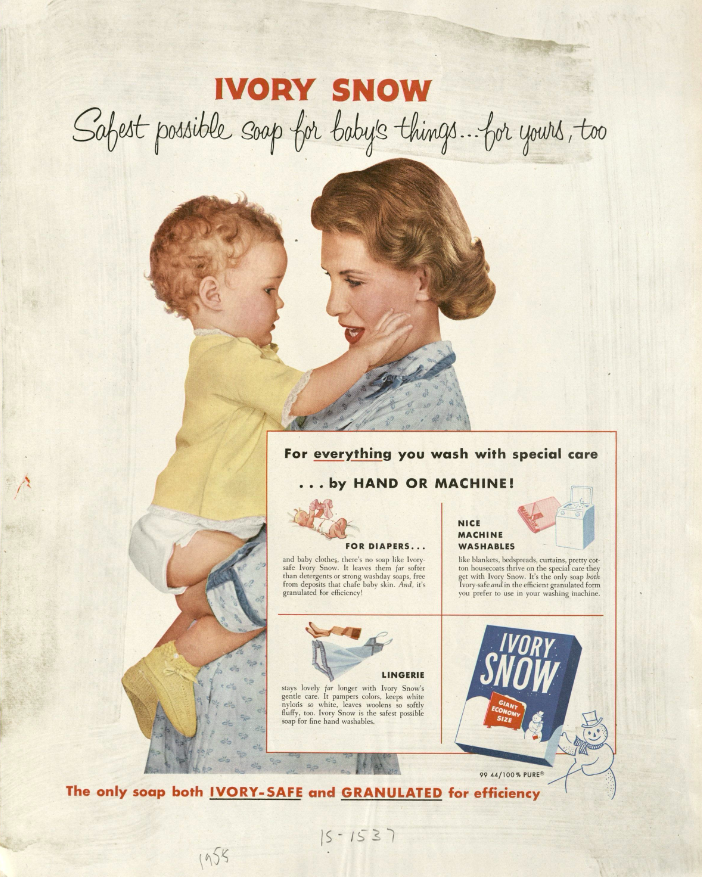

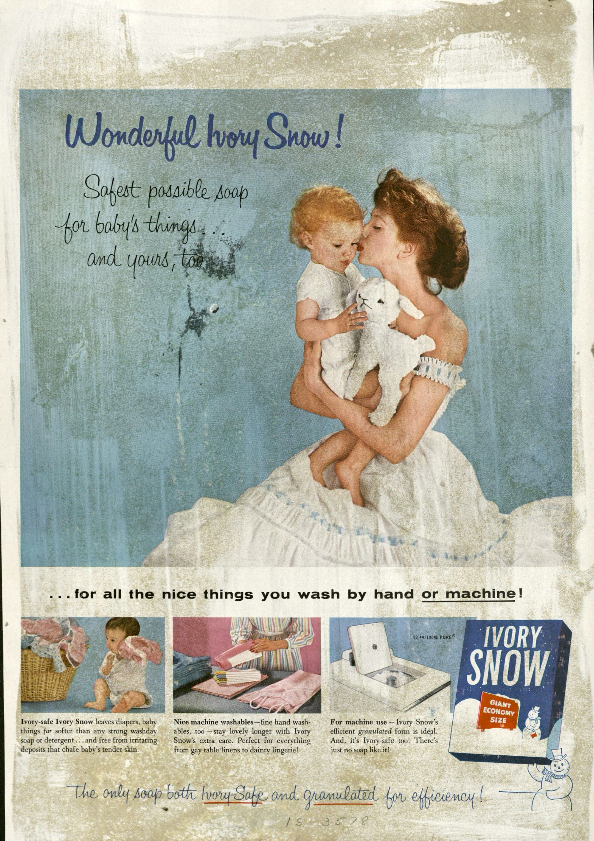

Ivory Snow, a soap company, portrayed the notion of women as the sole caretakers of children most prominently. In these ad campaigns, which ran throughout the 1950s, one can find phrases such as, “My mommy washes everything nice in Ivory Snow!” Other ads represent mothers and babies with the catch phrase “…for everything you wash by hand” – you, meaning the mothers, of course. By only showing mothers and children when advertising children’s products, not only were women pressured to have adorable children and fall effortlessly into their domestic duties, but fathers were nowhere to be found and therefore not expected to parent.

Images: D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles, Box 112.

“As we try to understand our situation as women, we keep coming up against a central issue: we’re told our first job is to care for our children — alone, in our homes, all the time…. In our society, children are treated legally, socially, and personally like property. In our male-dominated families, this means that children belong to women, who in turn belong to men.”

– Mothers and Children

Caroline Bien, who worked as a copywriter and executive at many different advertising agencies from the 1960s to the 2000s, noticed this mother-dominated trend. She remarked, “I don’t think we would have ever put fathers in [advertisements] at that time. It wasn’t until later that fathers started to do more motherly things – lets put it that way. So, that never came up.”

Miss Clairol ran advertising campaigns in both Ladies’ Home Journal and Essence Magazine trying to sell their hair color by directly advertising to mothers and showing women with their children. If you did not want to be a mother, you were left out of advertising. Apparently, only mothers dye their hair.

Images: ProQuest Essence Magazine, Volumes 1 & 2. Ladies’ Home Journal, Box 87.1.

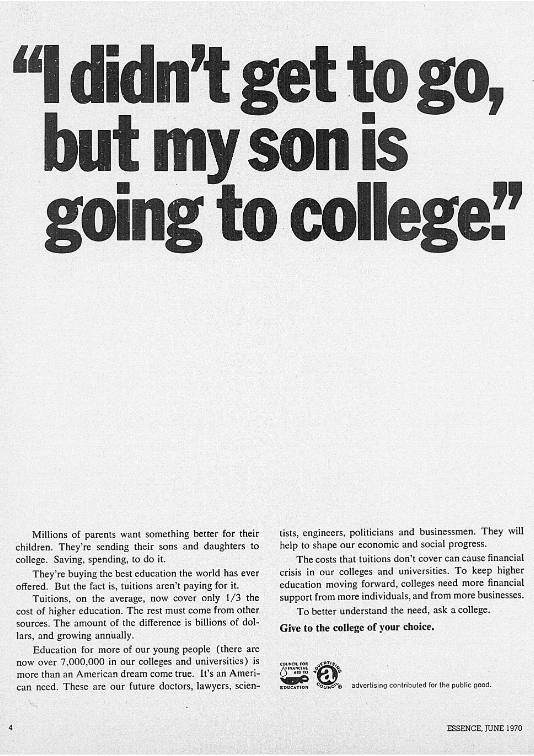

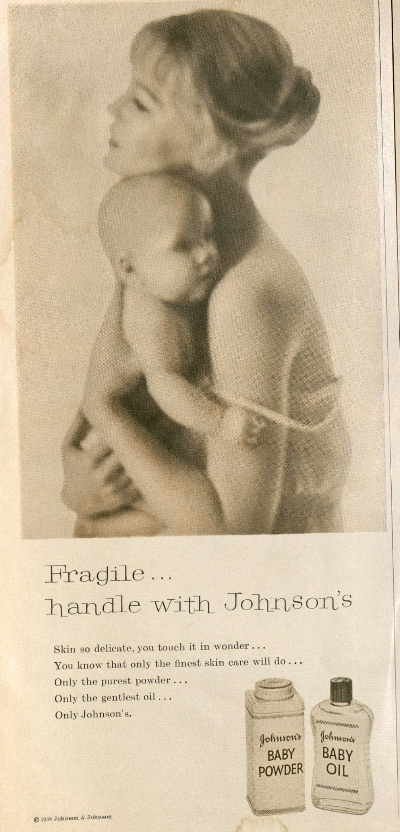

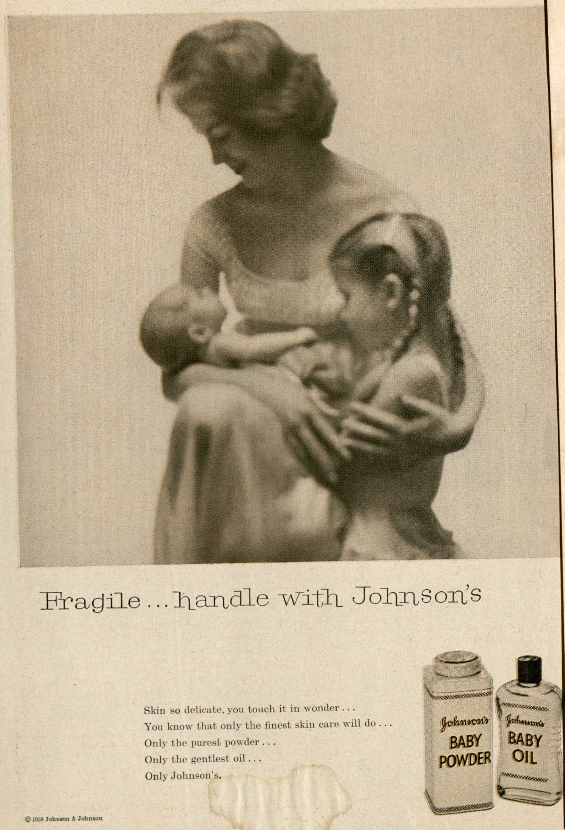

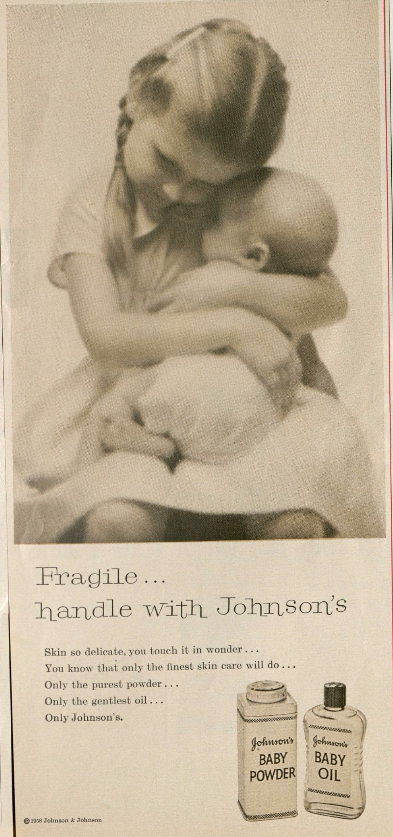

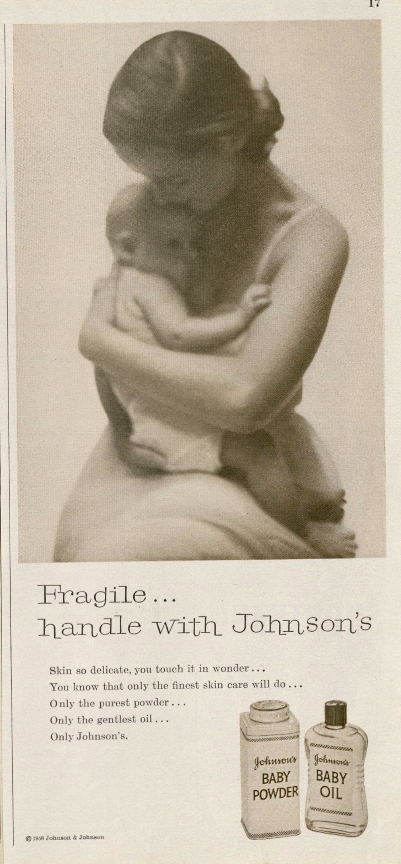

In the 1958 Johnson & Johnson ads below, it is made perfectly clear the narrative of breeding that advertising was trying to accomplish. These ads unapologetically portray mothers taking care of babies, mothers showing their daughters how to take care of babies, daughters taking care of babies, and ultimately, daughters growing into mothers.

Images: Roy Lightner Collection of Antique Advertisements, Box 5.

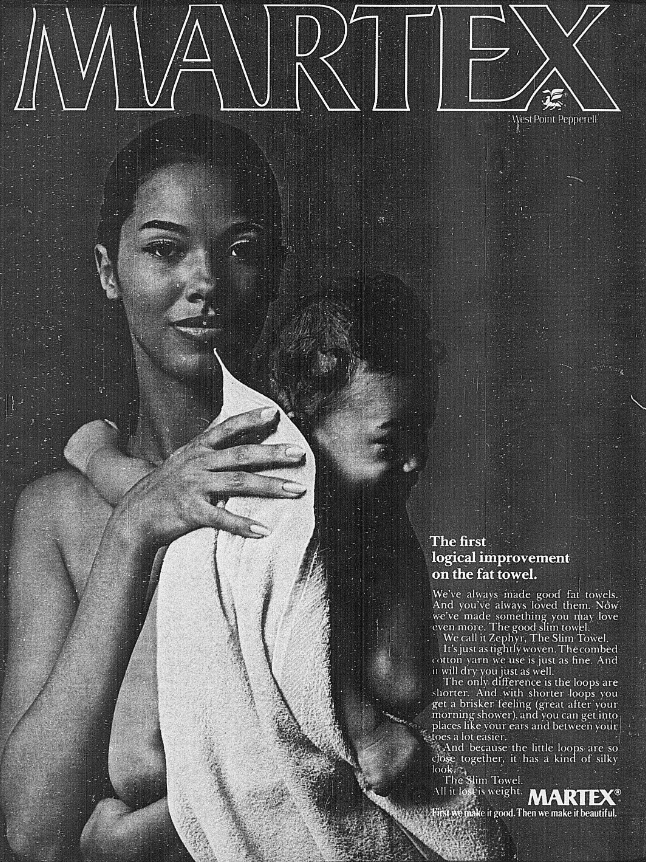

In 1970 Ti-Grace Atkinson, member of the National Organization of Women and founder of The Feminists observed that in advertisements and commercials, “women are shown exclusively as sex objects and reproducers, not as whole people.”

“Women are shown exclusively as sex objects and reproducers, not as whole people.”

– Ti-Grace Atkinson, 1970.