Women of Color & Sterilization Abuse

Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance Archives, Box 13.

For women of color, the reproductive rights movement was not as straightforward as demanding access to abortions and birth control. While advantages were being made for the white and the wealthy, women of color were being left behind in the face of an entirely different fight for control over their bodies.

Beginning with the creation of the pill in the 1950s, women of color suffered from the reproductive rights movement. The pill was tested on Puerto Rican, Haitian, and Appalachian women for almost a decade before it was approved by the FDA in 1960 and distributed to American women. That period of time was not only used to record the effectiveness of the pill, but also its safety to women’s lives and the ability of women to conceive after they stop taking it.

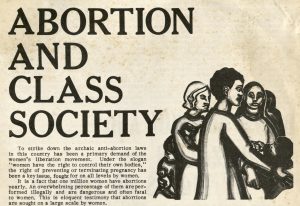

The pill was used as a weapon against women in the Global South and sterilization, a weapon against poor women and women of color in America. (Abortion and Class Society.)

“It appears sterilization of minority and poor women is a major, unpublicized weapon in the U.S. government’s domestic “war on poverty.”

– No More Genocide! Women of ALL Red Nations Unite, 1980.

Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance Archives, Box 13

Sterilization Abuse

In the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, sterilization was much more common for women. It was a quick and easy option that ensured the confidence of not having to worry about pregnancy. While many women chose this form of birth control, others were forced into sterilization either against their will, in order to survive, or unknowingly.

In the 1970s, multiple states (including Alabama, California, Delaware, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) attempted to pass sterilization laws. Many of them were linked to welfare regulations “so that poor Black, Chicano, Puerto Rican, and white women are forced to submit to sterilization in order to stay on welfare.” One law proposed in Tennessee explicitly stated that “‘women with one of more ‘illegitimate children’ must submit to sterilization if they want to retain welfare benefits.’” (Abortion and Class Society)

‘Voluntary’ abortions were also proposed to women who would be unable to continue receiving assistance if they had more children. However, when poverty and racism made these ‘voluntary’ decisions necessary for survival, they became mandatory.

Black Women

One newspaper article from 1973 describes an instance of sterilization abuse against black children that is extremely disturbing and allows the gravity of this issue to become more clear. Three sisters, ages 12, 14, and 16, were driven to a hospital with their illiterate mother and were sterilized. The mother had given her consent, but being unable to read the document, she believed what she was told which was that her daughters were getting their birth control shots. After the medical officials were confronted, they rationalized their abuse by saying that the young girls were “retarded.” (Sterilization: The Politics of Birth Control, 1973)

Similar abuses were taking place across the country against black women. Almost ten years earlier than the sterilization of the three sisters, in 1964, it was revealed that in Sunflower County, Mississippi, as many as 6 out of every 10 black women had been sterilized and were often not informed of what had been done to them until the procedure was complete. (Abortion and Class Society)

Indigenous Women

While much of the sterilization abuse against black women came from individual medical providers or clinics, most of the sterilization abuse against indigenous women came directly from the government.

Through the Indian Health Services Department, uninformed sterilizations on indigenous women took place at an alarming rate. In the early 1980s, president of the United Native Americans, Lee Brightman, estimated that of the 800,000 indigenous peoples in America, “as many as 42% of the women of childbearing age” had been sterilized. This estimate is uncertain because hospital records on procedures were often incomplete or “lost,” and for some women, they would not discover what had happened to them until years later. (No More Genocide! Women of ALL Red Nations Unite, 1980)

“The weapons in this campaign are not the guns and epidemics which nearly accomplished this [genocide] in the 19th century.”

– No More Genocide! Women of ALL Red Nations Unite, 1980

“Population Control”

Many of these acts of sterilization abuse (both forced and ‘voluntary’) were commonly justified as population control.

Now, of course, this justification seems absurd, as the world population in the 1970s was less than half of what it is in 2019. However, many groups and individuals used overpopulation to rationalize abuse.

“The fear of “too many people” as voiced by the U.S. government is really a fear of too many poor people and especially too many black and brown people.”

– Women and Contraception

Without legislation or clinics forcing abortion, the accusation that it was poor women and women of color who were creating a population too large to support, pressured women to have abortions or take birth control, as well. Finding birth control was not difficult because it was often widely available, cheaply or for free in poorer areas. (Birth Control and Abortion: Some Things to Worry About)

“Women must be able to obtain free and legal abortions, on demand. But it should be pointed out that unless this right is controlled by the people it effects — namely, WOMEN and non-white people, it will be used in the very same genocidal manner that birth control is being used today against poor and non-white people.”

– Women and Contraception

Black Genocide

In many ways, sterilization abuse and provision of birth control were forms of genocide against black people. According to the Genocide Convention of the UN, created in 1948, one of the five genocidal acts are “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.” Some black men took advantage of this argument to try to control the bodies of black women.

In one publication titled Birth Control Pills and Black Children black men writing to black women said “The Brothers are calling on the Sisters to not take the pill. It is this system’s method of exterminating Black people here and abroad. To take the pill means that we are contributing to our own GENOCIDE. However, in not taking the pill, we must have a new sense of value. When we produce children, we are aiding the REVOLUTION in the form of NATION building.” (Poor Black Women, 1968)

Some black women agreed. Linda Roots wrote in Essence magazine: “”Black mothers, keep on keepin’ on, for Nationhood depends on Motherhood” (Point of View on Motherhood, 1971). She described how essential motherhood and having children is for black women and the black community as a whole. Writer Kay Lindsay expressed “many of us will decide that the greatest contribution we can make to the nation is a child, as an expression of love and reaffirmation of faith in a black future.” (Birth Control and the Black Woman, 1970)

Others were clearly torn by the issue. “I don’t want my people programmed for genocide,” replied a young mother of two in an Essence Magazine interview when asked what she thought of the pill. “I use birth control, but I think black women should have as many babies as they can,” she said. (Birth Control and the Black Woman, 1970)

Still, the majority of black women acknowledged the abuses taking place against them but did not let it stand in their way of controlling their bodies. In The Sisters Reply, they say “Poor black sisters decide for themselves whether to have a baby or not to have a baby. […] For us, birth control is freedom to fight genocide of black women and children. […] Poor black women in the U.S. have to fight back out of our own experience of oppression.” (Poor Black Women, 1968)

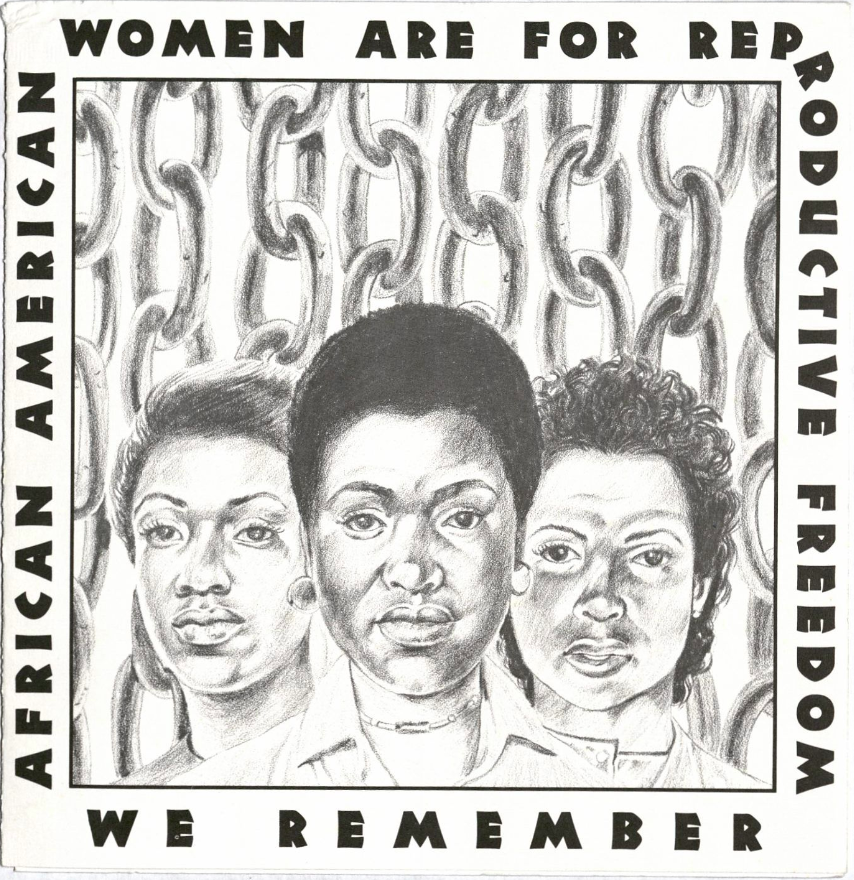

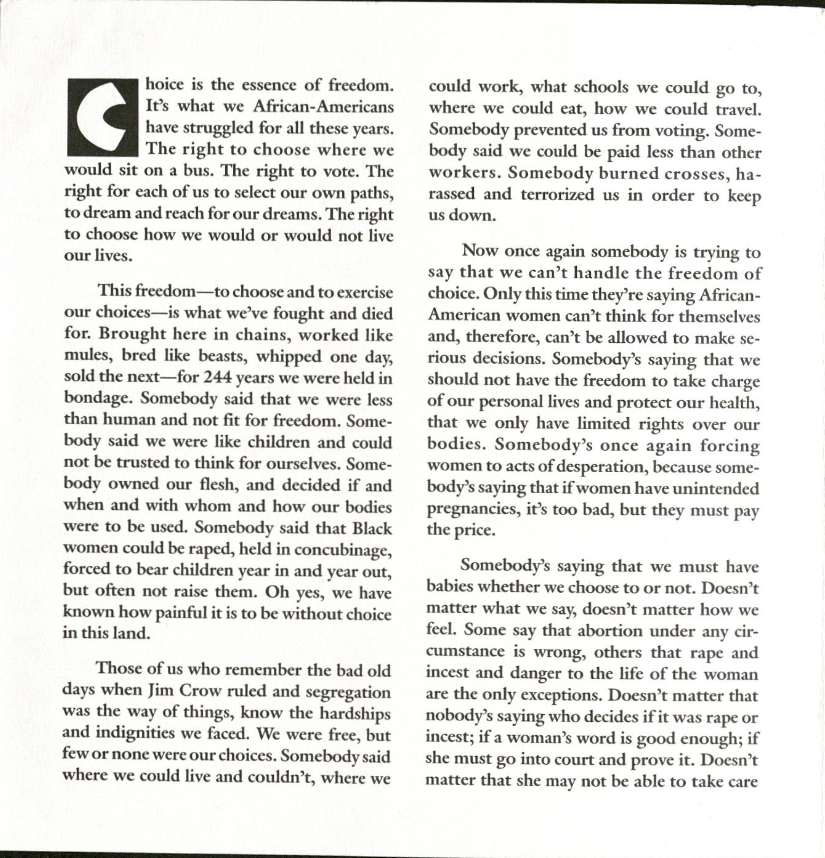

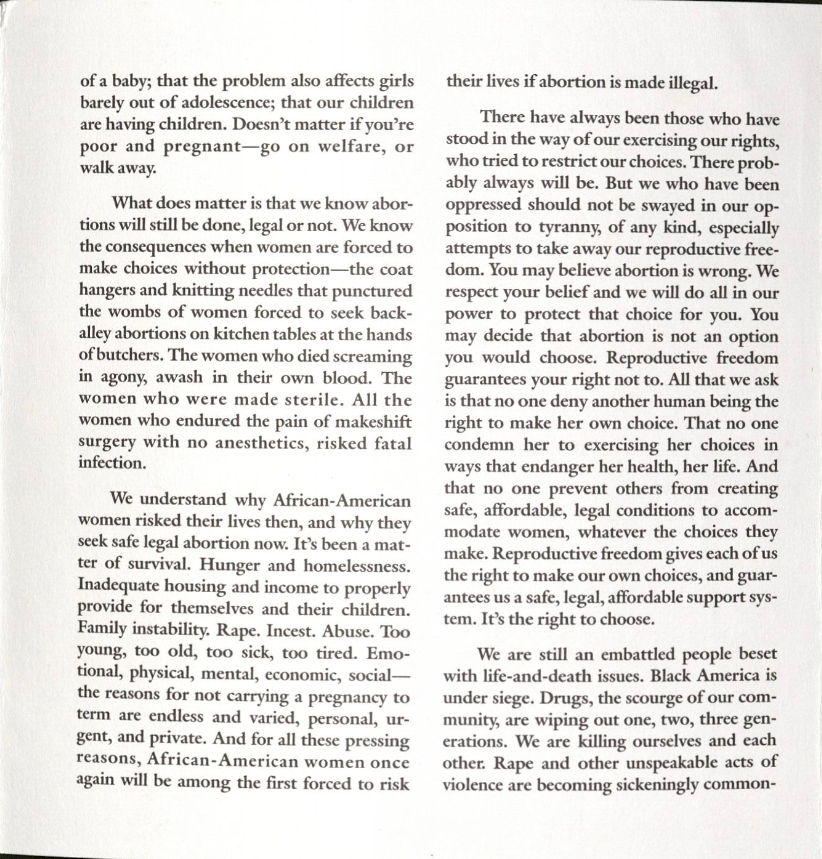

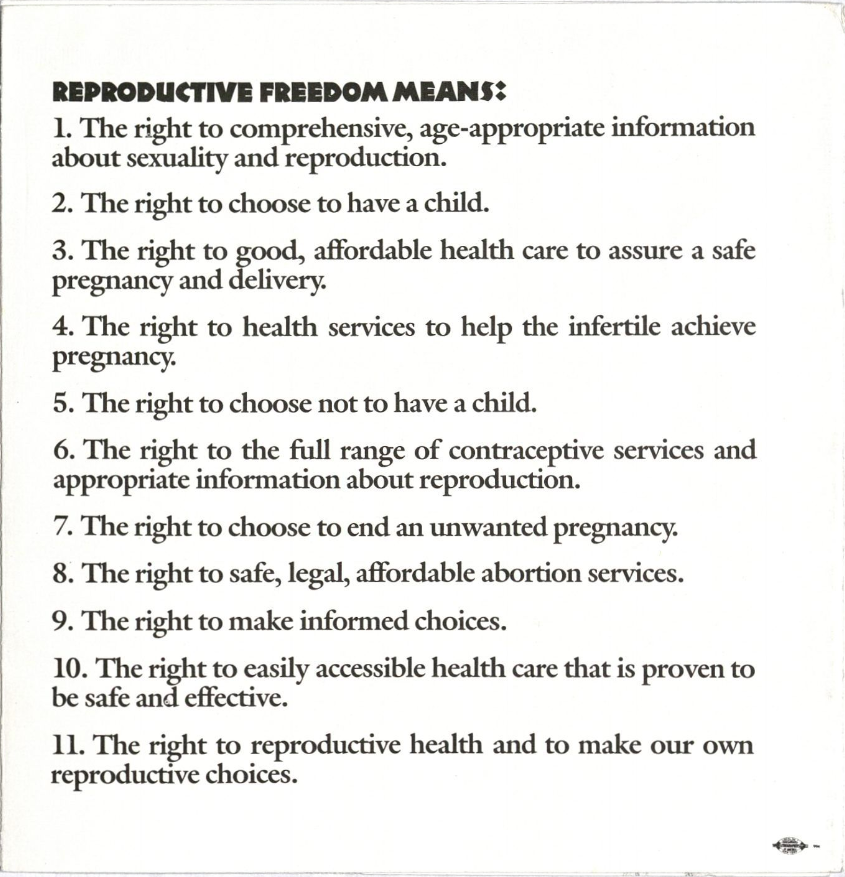

The pamphlet below shows this verve for reproductive freedom from black women.

Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance Archives, Box 13 .

On black men fighting against their access to these freedoms, one woman responded with “birth control is none of their business.” (Birth Control and the Black Woman, 1970)