Prescriptive literature provided guidelines and blueprints for women of the 50s, 60s, and 70s on how to properly be women, wives, and mothers. These guides presented a very one-dimensional snapshot of what a woman should be. Similar to the way that advertisements forced the ideal of women as mothers, much of prescriptive literature also implied that motherhood was a requirement for womanhood and vice versa.

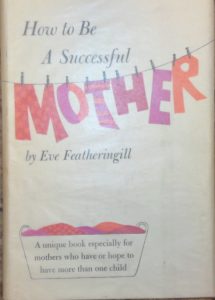

How to Be A Successful Mother, Eva Featheringill, 1965. Prescriptive Literature.

One such guide, entitled How to be a Successful Mother, was written in 1965 by Eva Featheringill. The book’s goal is to outline the steps one must take (including feeding, clothing, and caring for a baby while maintaining a home) to be a successful mother. However, messages of women’s subservience and purpose are strewn throughout. One of the most prominent quotes is at the beginning of the book: “Men, it seems, grow up by finding themselves. Women set out to find meaning by marrying and having children.”

“Men, it seems, grow up by finding themselves. Women set out to find meaning by marrying and having children.”

Immediately, the book implies that a woman’s purpose comes from being a wife and mother. Her husband and child are everything to her, because they are a representation of her essence. One chapter is entitled, “A Family Begins with One Baby.” Without that baby, the woman becomes an orphan, as the presence of children makes a family.

On the form of marriage and the roles of men and women, Featheringill says “with marriage, the machinery of our “roles” takes over at once.” Roles, of course, is here referring to the man’s role as the one who works and brings in income, while the woman stays home and tend to the house and children. By using the word “machinery,” one could conclude that Featheringill feels these roles are inherent and natural; that motherhood is the “job” of women, as it is often referred to in the book. This belief spread beyond just one author, and by putting these beliefs within prescriptive literature, they were likely being forced upon the women who read them.

When giving advice, Featheringill explicitly states “I assume you’re not working (your first child is small), and I take for granted your husband’s job is stable – or at least predictable.” There is no hiding behind the facade of feminism. This book and others like it are explicit in their complacency with gender roles.

As if it was not already implied that women serve men, the baby is referred to throughout as a “he.” The women must take care of the men in all ways at all ages; from birth to adulthood, she cares for him.

“It’s not your day, it’s the baby’s,” the author exclaims. Women lose all anonymity and are nothing more than mothers. It tells women that they will find they “need” to have more children, and will “like just about everything” in their lives, if only they follow the simple steps in this book.

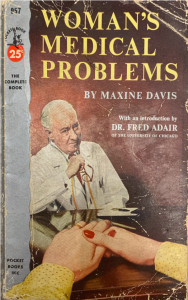

Woman’s Medical Problems, Maxine Davis, 1953. Prescriptive Literature.

These messages were everywhere. Even in a 1953 book of prescriptive literature entitled Woman’s Medical Problems, the idea that all women were mothers and would have children was present throughout. The majority of the book is spent on pregnancy, miscarriage, abortion, contraception, and infertility. “You are going to have a baby,” author Maxine Davis makes known. “You always wanted to have a baby,” she says.

Dr. Jean Kilbourne, feminist and media critic, said “It seemed like such a given that women should want to be mothers and that this was the ultimate experience for all women, and this was rarely challenged in those days.” Maxine Davis makes this explicit in her book.

In Woman’s Medical Problems, pregnancy is described as “one of the most important events in any woman’s life” and having a child, “one of the profoundest needs of humankind.” Infertility is “depriving your husband of his right of fatherhood.” Childless marriages are “sad” and careers are not a “real competition” to motherhood because women are usually “glad” to give up their jobs to be mothers (if they ever worked at all).

Women who do not want children are “relatively rare” according to Davis. The reasons for not wanting to have a baby are shallow with a select few women not wanting to “ruin their figures” or “be tied down.”

———

All of these messages found in prescriptive literature served as subliminal counterarguments to the reproductive rights movement. With ideas of motherhood being presented as the only realities for women, fighting for access to birth control and the legality of abortions did not necessarily align. In the chapters on abortion and contraception in Woman’s Medical Problems, these previously implicit protests against the movement are made explicit.

Birth control is referred to in Woman’s Medical Problems as an “ethical problem” and abortion “one of the tragedies of mankind” and a “sin against the one of the most profound instincts of the [human] race;” a sin against “the law, the Church, and nature.” Davis goes on to call abortion “evil” and “immoral.” And if all of that was not enough to make it clear that to see women as mothers was to be against the reproductive rights movement, Davis gives explicit orders: “Bear your baby.”

While women tried to fight for the right to control their bodies, they not only had these narratives standing in the way, but they were also influenced and affected by these portrayals of women. Ms. magazine did a story in 1976 that showed how the necessity of motherhood made women feel. Those without children, regardless of their work, were left feeling like “the ‘barren’ woman, the human failure.” Those who thought they could ignore the influences of prescriptive literature and advertisements showing women as mothers were simply not looking hard enough (A Challenge To All Your Ideas About Motherhood & Daughterhood, 1976).

While women tried to fight for the right to control their bodies, they not only had these narratives standing in the way, but they were also influenced and affected by these portrayals of women. Ms. magazine did a story in 1976 that showed how the necessity of motherhood made women feel. Those without children, regardless of their work, were left feeling like “the ‘barren’ woman, the human failure.” Those who thought they could ignore the influences of prescriptive literature and advertisements showing women as mothers were simply not looking hard enough (A Challenge To All Your Ideas About Motherhood & Daughterhood, 1976).

“Any woman who believes that the institution of motherhood has nothing to do with her is closing her eyes to crucial aspects of her situation.”

– Adrienne Rich, 1976.