Representation of Women in Advertising in the Mid-Twentieth-Century

This timeline shows the evolution of women in advertising from WWII to 1980. During the war, women were shown in working roles; afterwards they were almost exclusively displayed as housewives and sex objects. In response to the demographic shift of women into the workforce and the women’s liberation movement in the 60s and 70s, advertisements started to adopt a glamorized version of the working woman, dubbed the “new woman” or “superwoman.”

The Housewife and the Sex Object

Although women accounted for almost half of the workforce by the 70s, advertisements had not caught up. Below, quotes from advertisers and their critics speak to this misrepresentation of American women in advertising.

“New Woman,” New Stereotypes

“The first thing that happened, was that we went from the kind of stereotype when I started out – women as sex objects or women as wives and mothers, women obsessed with cleanliness, with making your kitchen fit for surgery – and then what happened with the coming of the second wave of feminism, and the co-optation of feminists, was the image of Super Women.”

–Jean Kilbourne, 2019

As advertisers began to co-opt the women’s liberation movement, they created new, but equally problematic stereotypes about women. Advertising critics tell a story of false progress in the portrayal of women in the ad world, pointing out the persistence of sex object stereotypes and the creation of the new “superwoman” stereotype.

On the one hand, there was very little change in the roles that women played in advertisements at all. Women still continued to be portrayed as homemakers and sexual objects. A University of Michigan study from the early 80s found that sexual stereotyping did not change at all from 1960 to 1979. During two decades of social change, advertisers consistently portrayed women modeling clothes or performing domestic work, while men were depicted on the job and rarely in the home (The New Woman in the Eyes of the Media, 1984).

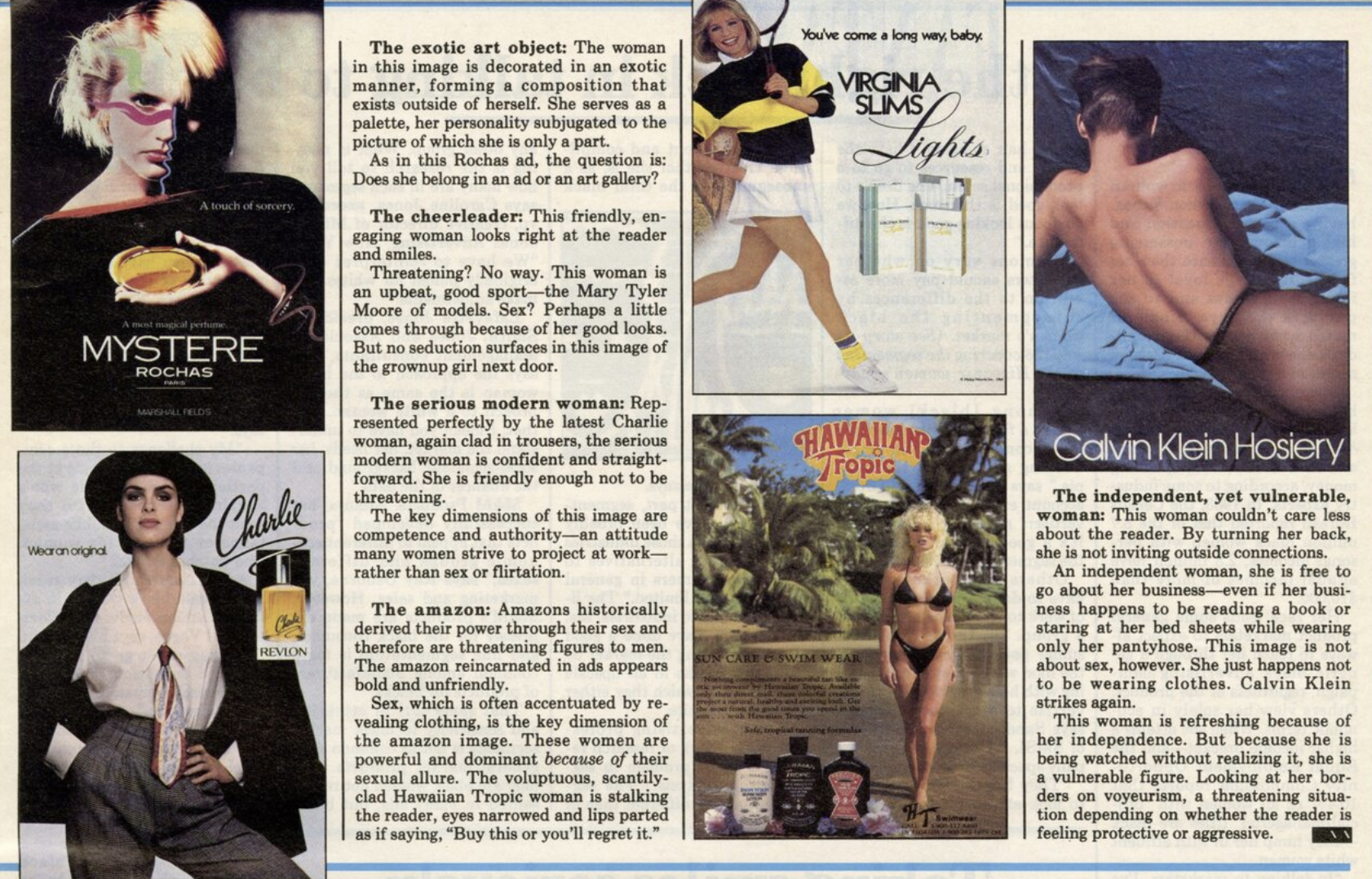

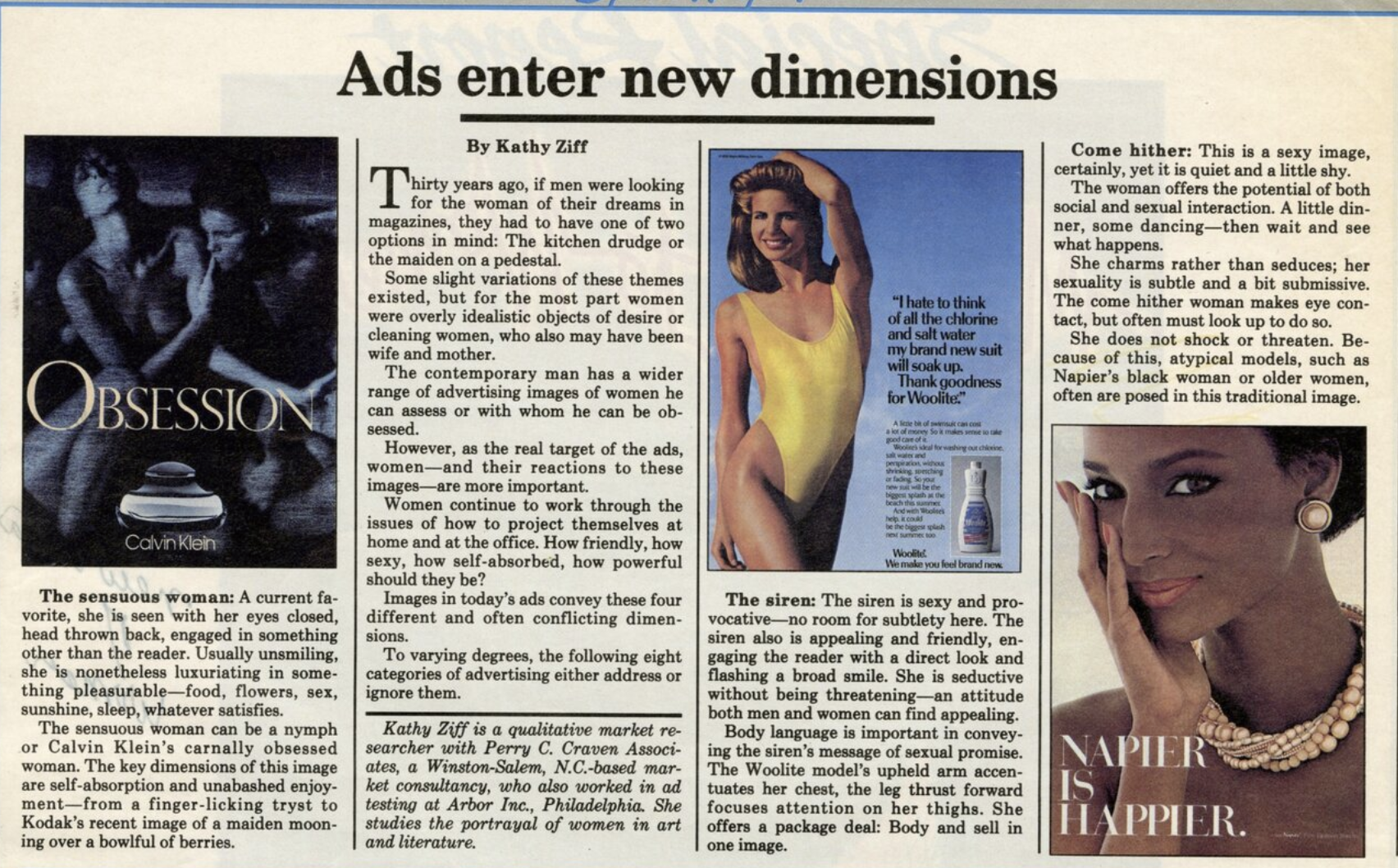

Take a look at this 1985 Adage article, which shows a few variations on the sexual object stereotype. While the sex object stereotype may have undergone some changes since the 60s, the underlying message that these women existed for the consumption of men was still clear. In the words of the author of this article, “The contemporary man has a wider range of advertising images of women he can assess or with whom he can be obsessed.” (Ads Enter a New Dimension, 1985)

Source: Jean Kilbourne Papers, Box 35

The Problem With “Superwoman”

“Women today really do insist they can do it all. They firmly believe that they can handle marriage, family, and career all at the same time and do it well. What they need then, are products designed to help liberate them from their chief enemy, the clock.”

-Tina Santi, Corporate VP Colgate Palmolive, 1979

When the working woman was represented, it tended to be an in unrealistic and glamorized manner. This “new woman” was not only expected to succeed in the workplace, but also expected to keep up with domestic chores at home and keep her husband happy. This new stereotype created a new type of pressure for both working women and women at home. Jean Kilbourne explained how this stereotype “was really a problem” because “she created an impossible standard that added to the stress women felt and normalized that women were supposed to do this effortlessly without any help from their partners or – god forbid – the government.” By proposing products as the solution to these new problems, advertisements created a distraction from underlying gender inequalities that could only be solved through real social and policy change. These ads projected the illusion that women had achieved equality when in truth, they still continued faced sexism in the workplace and all walks of life.

In the following interview clip taken from a McCann presentation on women in advertising, an advertiser interviews magazine editor Judith Daniels, feminist spokeswoman Gloria Steinem, and Working Woman editor Kate Rand Lloyd on their opinions about new stereotypes of working women in ads.