Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

Introduction

This is case study on the development of J. Walter Thompson’s Advertising and Marketing Intelligence (A.M.I) database. The exhibit applies different feminist frameworks to uncover the gender dynamics within A.M.I. as a representative example of information and data technologies during the late 1970s. This work draws on documents from the “Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records 1979-1982” found in the John H. Hartman Center on Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History and on feminist theory found in the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History & Culture.

Topics in this section include:

- Connections between the advertising, media, and data/information industry

- Financial and technical development of A.M.I

- Feminist analysis using popular post-war feminisms

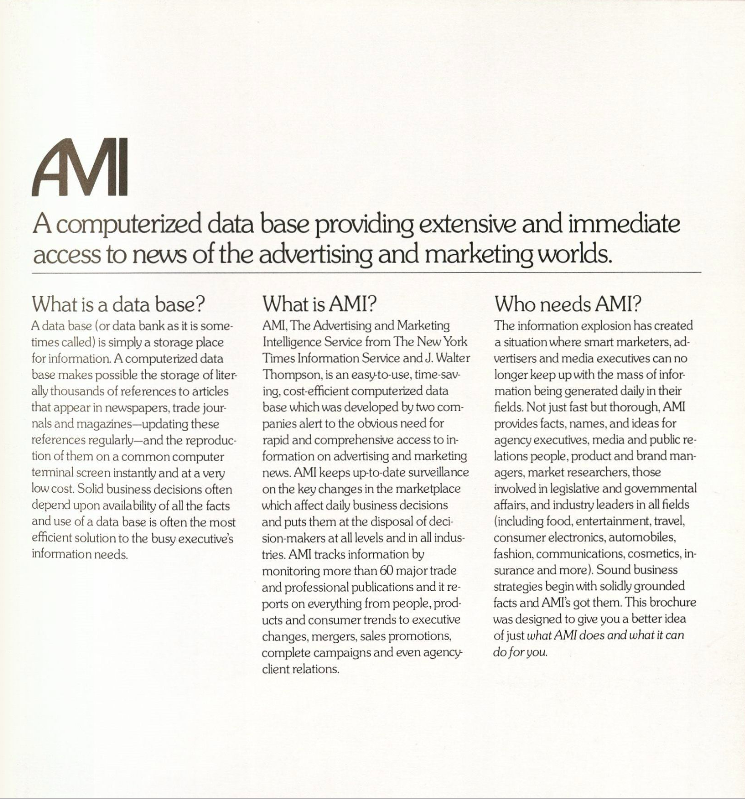

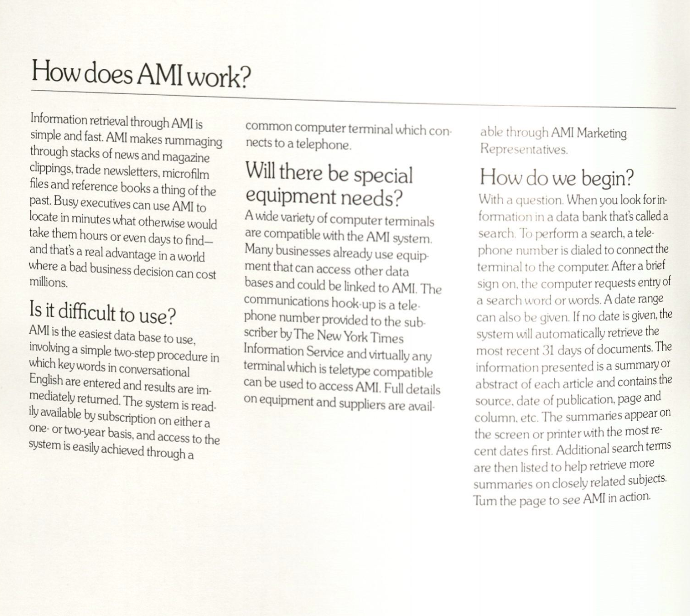

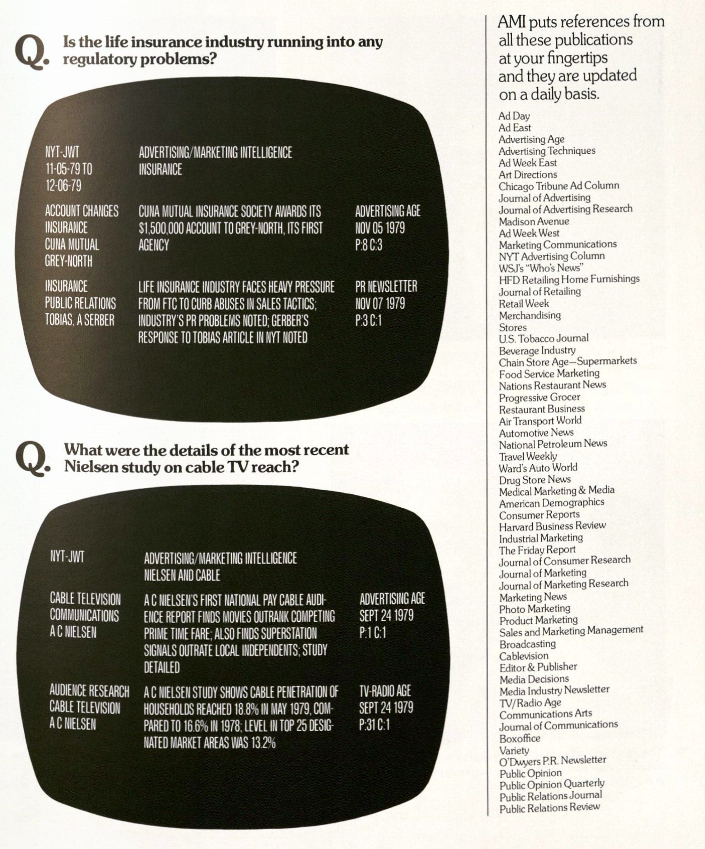

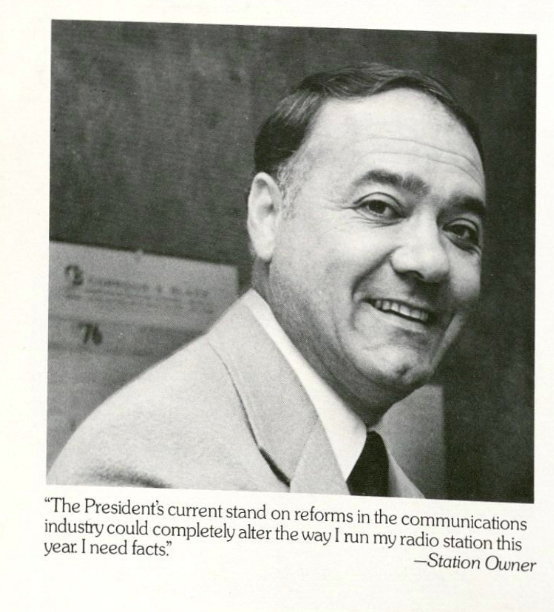

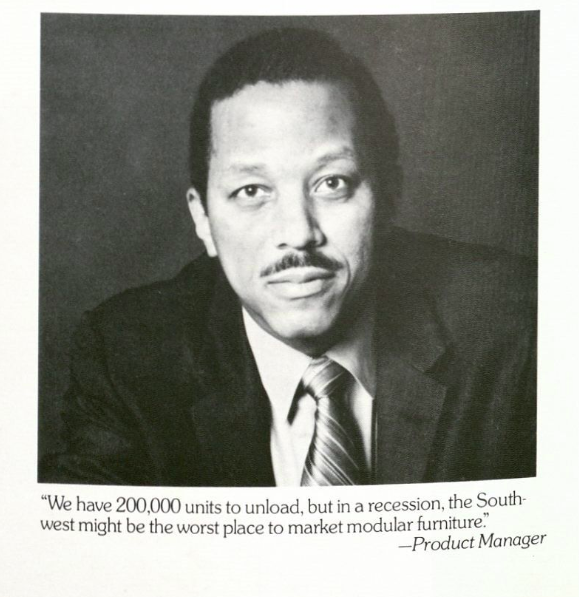

The gallery below includes printed press materials advertising A.M.I. and explaining its uses.

Gallery 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

Background: Advertising Enters the Information Industry

In 1979, J. Walter Thompson became one of the first advertising firms to develop a database that digitized information about marketing and made it available online. The “Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database,” or A.M.I., was built from 1979 to 1982 in conjunction with The New York Times, the Carter Administration, and the Reagan Administration. The A.M.I. database stored abstracts of articles, studies, and information from publications related to advertising and marketing.

The advertising industry – particularly J. Walter Thompson – seemed to consider itself on the forefront of the “information revolution” for a variety of reasons, namely that advertising was in the business of information. J. Walter Thompson also led the advertising industry in part because of its obsession with information. JWT was notorious for conducting extensive consumer surveys, focus groups, and door-to-door interviews about products, consumer psychology, and market trends.

In early 1979, the New York Times granted J. Walter Thompson access to its “Key Issues Tracking Data Base.” The NYT database was comprised of abstracts of articles related to economics, politics, and culture, stored and searchable on a computer. The JWT version would be similarly structured, but focused on advertising and marketing, and its services would be available for leasing.

Gallery 2 summarizes JWT’s collaboration with The New York Times and their final product:

Gallery 2

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

Gallery 3 includes documents related to J. Walter Thompson’s motivations for entering into the data industry and its collaboration with the New York Times. Of note is JWT’s summary of the historical development of the database industry, claiming it has “for the most part, evolved as a by-product of other better known information activities.”

Gallery 3

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 3 c. 1

Gender and the New Information Market

JWT’s growing interest in the information market may have been gendered in other ways too. In the 1970s, when it became more clear that information and computer technologies would be profitable and powerful, men and male-led companies began to show more interest in these fields. As more men entered the technological sciences, they made the field both lucrative and prestigious. This trend is highlighted by a socialist feminist framework, in which capitalism and patriarchy cannot be separated from each other. It is also supported by recent studies, which show that wages tend to rise when men enter a female-dominated profession, like computer science, and wages tend to drop when women enter a male-dominated profession. Thus, from a socialist feminist perspective view, men’s participation in the data and information industries has both capitalistic and patriarchal motivations and effects.

Development of A.M.I.

J. Walter Thompson needed to determine what information should be included in their advertising-specific A.M.I. database, and how to use and monetize this information. These decisions and developments impacted women’s lives in a variety of ways.

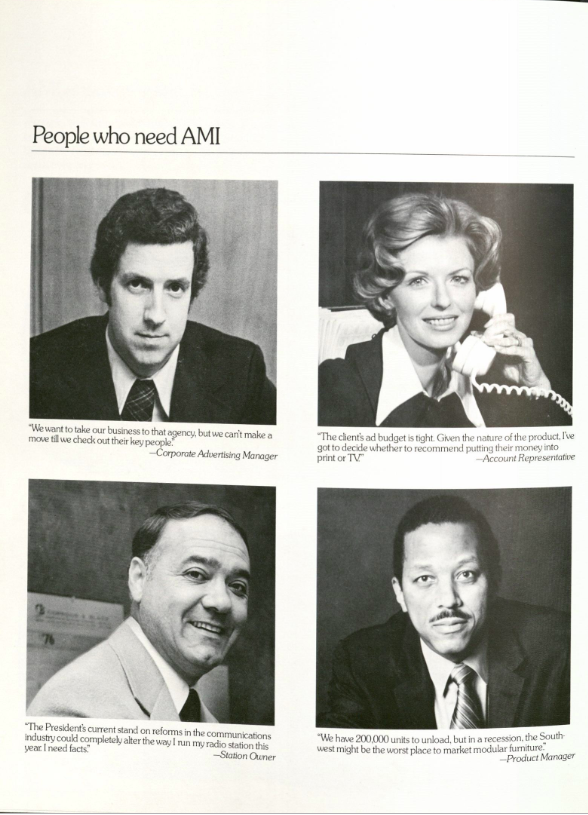

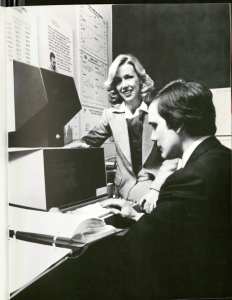

As noted above, many men moved into the data industry in the late 1970’s, even as women continued to use data processing software. This transition period – in which both men and women participated in technology – is reflected in various documents related to A.M.I, such as this A.M.I. advertisement for “People who need A.M.I”, seen in Gallery 4.

Gallery 4

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 3 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 3 c. 1

There were also several women who led the technical, legal, and professional development of A.M.I, according to this “Cast of Characters” document in Gallery 5. Nancy Harding was the Manager of Computerized Information Resources (although it is interesting that this document specifies who she reports to, a man named Bob Popper.) Paula Dincecco was a Marketing Information Analyst, who “knows the most about advertising research applications.” Jill Currie was another Marketing Information Analyst, who “knows the most about the administrative details of AMI” (suggesting a clerical role.) Marla Gordon was a former attorney on the project.

The inclusion of women and black men in A.M.I development is noteworthy, but perhaps more so to the liberal feminist perspective than to radical or socialist/Marxist feminisms. For the latter frameworks, gender and racial equality extends beyond advertisements or power in the workplace.

For example, the data entry work needed for AMI could be another particularly isolating form of labor for women. Furthermore, patriarchy could also be located in technology and uses of A.M.I. itself.

For instance, a prevailing idea some JWT employees seemed to have about A.M.I. was that it was “unbiased,” “accurate,” and operated by “objective” humans, as described in this document. As Feminist(s) and Tech explores, the privileging of a “objectivity” over a human “subjectivity” is patriarchal in the sense that men (and white people) are considered to be “neutral” and “rational,” while women (and non-white people) are “other” and “irrational.”

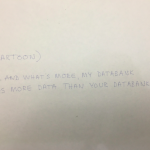

Another example of A.M.I, and more generally information science, being presented with a stereotypically masculine, hyper-competitive, and perhaps phallocentric bend is this cartoon mockup that reads, “…and what’s more, my databank has more data than your databank.”

Gallery 5

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

Like all technology, A.M.I was no less biased than its creators, input data, and users.

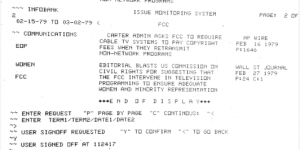

Another example of sexism within the A.M.I database could be the search results for the keywords “Women” and “FCC” in the New York Times database (which A.M.I. included.) Only one result appears, an abstract from a February 27th, 1979 Wall Street Journal article that reads: “Editorial blasts US commission on civil rights for suggesting that the FCC intervene in television programming to ensure adequate women and minority representation.”

Advertising and Marketing Intelligence Database Records, Box 1 c. 1, Folder AD/KIT

That editorial claims that attempts by the Civil Rights Commission and FCC to include more women and minorities equates to “regulating TV fantasies in order to assure they are politically acceptable – especially obnoxious.” Liberal feminist theory, which was especially concerned with women’s representation in the media would have likely objected to this characterization. And radical feminist theory might have used this as evidence that patriarchy is found embedded in various levels of technology.

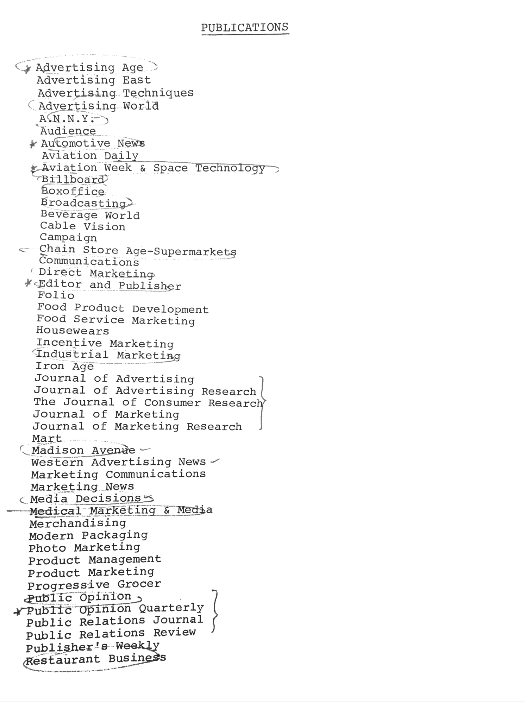

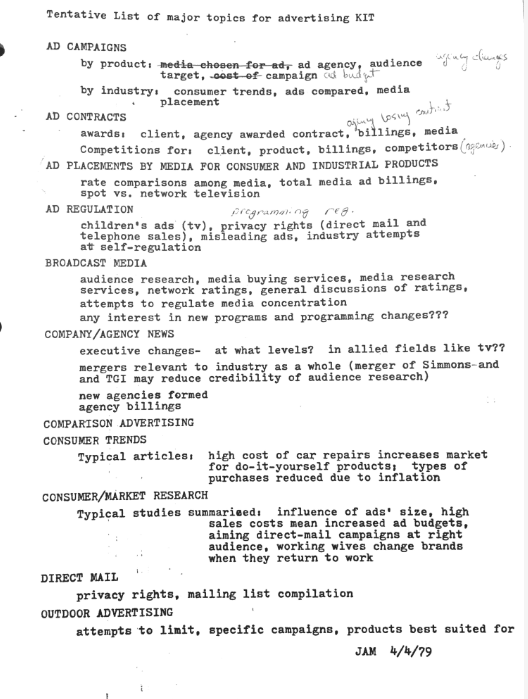

The gallery below is a list of publications and topics to be included in A.M.I. Of special note is the “Consumer/Market Research” section of the “Tentative List of Major Topics of Advertising KIT.” One “typical study” that would be included was “working wives change brands when they return to work.” It seems that one focus within marketing research departments with advertising firms during the 1970’s was women, and more technologically advanced methods of data collection might have had unique implications for women.

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

- Advertising and Marketing Intelligence database records Box 1 c. 1

Before the 1970’s, women’s consumer values were less researched and less “known” than male markets, with advertising executives content to use sexist stereotypes and infantilizing advertising campaigns. But in the mid 1970’s, Rena Bartos, a female advertising executive in JWT, argued that JWT should conduct more accurate research on women, use less stereotypes, and show variety in women’s lives – not because it was feminist, but because it was profitable. Bartos’ work culminated in a series of pamphlets and books called “The Moving Target.” As women gained more purchasing power in the 1970’s, research firms gained more technology to better research and influence women’s purchasing decisions, which is not necessarily a positive improvement, as socialist and Marxist feminist frameworks emphasize.

As seen in this gallery, another potential “public opinion poll” to be included in A.M.I. is “Polls on Political, Economic, and Social Issues,” such as the ongoing Women’s Liberation and Civil Rights Movements. This also reflects a reality in which advertisers researched political movements in order to co-opt them and sell products.

Thus, while the research improvements in A.M.I. may have made it easier to understand women’s behaviors, this was only a means to dubious, perhaps sexist, ends.