Agency Executives Resist Change

In the early 1970s, advertisers who recognized the importance of the changing roles of women were more of an exception than the norm. Although news of demographic changes in the workforce and the Women’s Liberation Movement had begun to enter the public consciousness, advertisers were slow to adapt. While critics believed depictions of women as household drudges were outdated, agencies were reluctant to change their marketing strategies. According to one adverting representative at P and G, “…what critics of this type of advertising have to face up to is that it works. The volume of mail we receive from the vast block of daytime TV viewers shows they do get excited by a box of soap. Our target consumer just isn’t that bright.” (The new American woman, 1970). His views were representative of many male advertising executives who continued to depict women the same way they had since the 1950s.

“The volume of mail we receive from the vast block of daytime TV viewers shows they do get excited by a box of soap. Our target consumer just isn’t that bright.”

-anonymous male advertising executive at Proctor & Gamble, 1970

Industry Women Sound the Alarm:

While most agency men dragged their feet, a small number of female advertising executives had already recognized the importance of changing demographics and attitudes in the women’s market. These women were frustrated by their male colleagues’ resistance to change. Francielle Cadwell of Cadwell and Davis Agency, paints a picture of her own experience dealing with stubborn agency men in the early 70s:

“Establishment thinking men equate their own masculinity with a woman being relegated to a subservient position. The typical advertising guy [did]n’t want to acknowledge this. It, both personally and in a business sense [was] distasteful to him, so he prefer[red] to say ‘that may be so in the Village, but in Peoria, Ill., that lady is the same as ever.’ Well that [was] not true. She [had] the means and the time to be a more free spirit. The power of suggestion is bombarding her every day through other women who are doing things. Physically she’s more and more free because she’s less strictly a child bearer. She has other options in life. And I think it will have its effect, but advertisers will probably drag their heels and finally be hit over the head before they respond.”

-Francielle Cadwell, marketing president, 1970

Some female executives expressed concern that outdated housewife tropes and sexist and belittling language would alienate female consumers. “When over 55% of the women in the country are high school graduates and 25% have attended college,” continued Cadwell, “when women have achieved sexual freedom, aren’t they beyond ‘house-i’tosis’? At the very least, women deserve recognition as being in full possession of their faculties… The revolution is ready, and one of women’s first targets will be moronic, insulting advertising. No force has demeaned women more than advertising.”(Coping With Women’s Lib, 1971)

Could it be possible that female advertising executives knew more about women than men did? Apparently so. It should come as no surprise that a 1970s survey of women’s perception of advertisements, of the 270 ads most disliked by women, all of them were produced by agencies without any women in executive roles. (Coping With Women’s Lib, 1971)

Even when women were present in the boardroom, without the evidence to back up their observations, female advertising executives had a hard time persuading their male counterparts to recognize that their advertising methods offended women. One female advertiser spoke to her experience with this: “We have a new beauty product at our agency” she said, “and I’ve been trying to tell the account group that women are beginning to resent advertising which portrays them purely as sex objects. Unfortunately, I’m in a difficult position because the people who are managing the account at the agency, especially since I’m in research, say, ‘Show me the proof. Show me the percentages of women who resent this.’” (The New American Woman, 1970)

Agency Men Listen

A few female executives amongst a large group of men at JWT in 1970, Rena Bartos Papers 1962-1998, Box 14

Fortunately, market researchers like Rena Bartos were hard at work collecting data on the image of women in advertising. The results were in: women were not happy. As Bartos put it:

“Even the most traditional-minded women did not want to be depicted as simpletons, helpless females, nags, shrews, catty gossips, or any of the other unflattering cliches which are currently used to exemplify housewives”

-Rena Bartos, 1974

In 1975 the National Advertising Review Board (NARB) decided to conduct the “Report On Portraying or Directed to Women” in order to address this issue. A panel of industry executives and experts reviewed samples of advertisements and critical literature to understand the basis of complaints about advertising that portrays women or is directed at them.

The panel was particularly concerned with the complaints of the “younger, better educated, more articulate women,” who they identified as the “opinion leaders” in the women’s market (Advertising and Women, 1975). These women took issue with the use of stereotypes perpetrating the ideas that: “a woman’s place in the home, women do not make important decisions, women are dependent on men and need their protection, and [that] men regard women primarily as sex objects–and are not interested in women as people.” (Advertising and Women, 1975).

Confronted by the criticism of young opinion leaders, the panel concluded that they would have to improve the situation in order to “provide a greater measure of fair treatment for women” and “second, [because] it will be an intelligent marketing decision.” (Advertising and Women, 1975).

Apparently, the NARB now understood the economic implications of continuing to market products in a way that insults the target consumer. With an increased number of women in the workforce, more women in managerial and executive positions, and the number of women in the upper-income groups seven times what it was in 1960, advertisers had no choice but to heed the complaints of this important market.

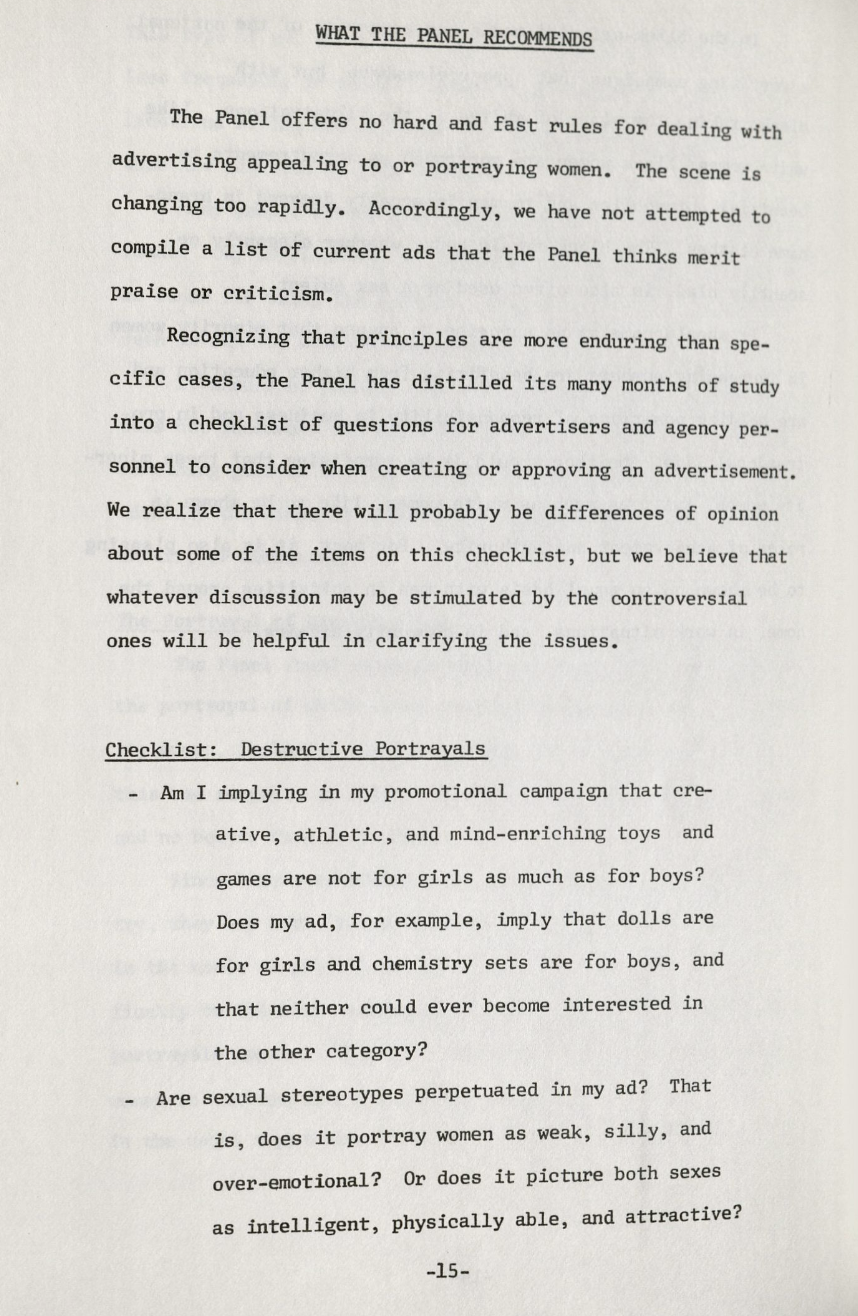

How to Not Offend Women According to the NARB

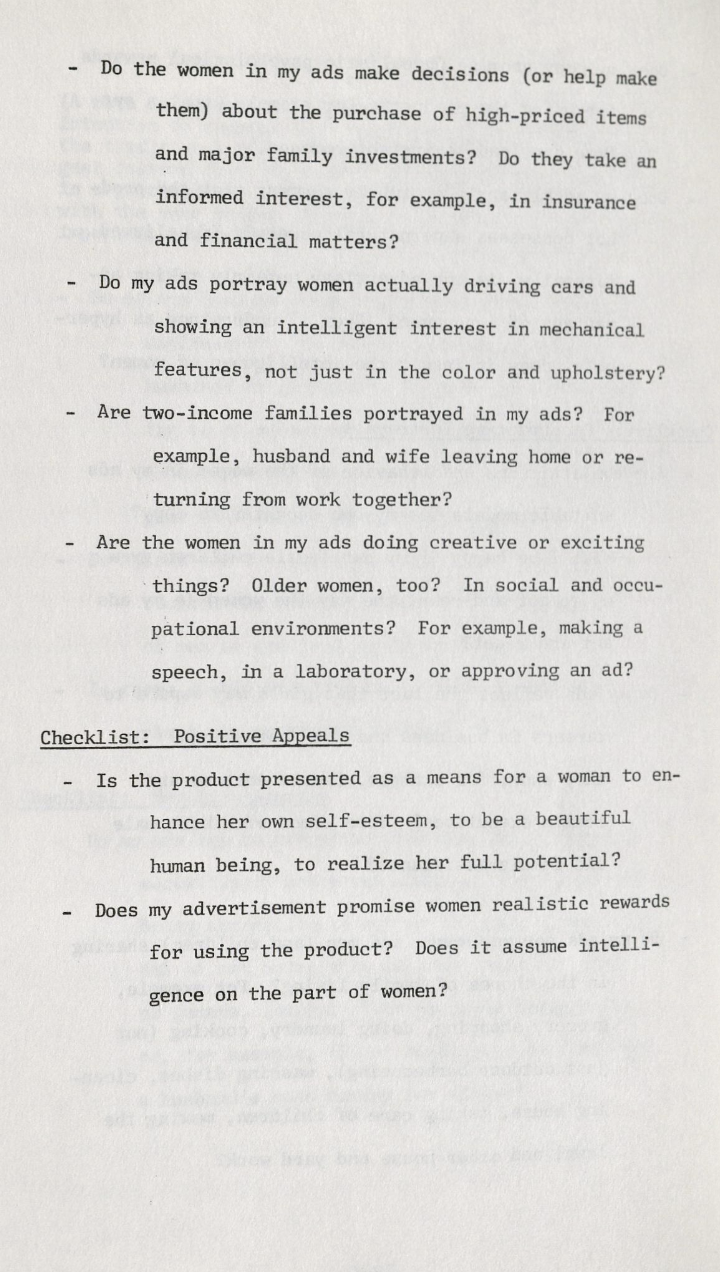

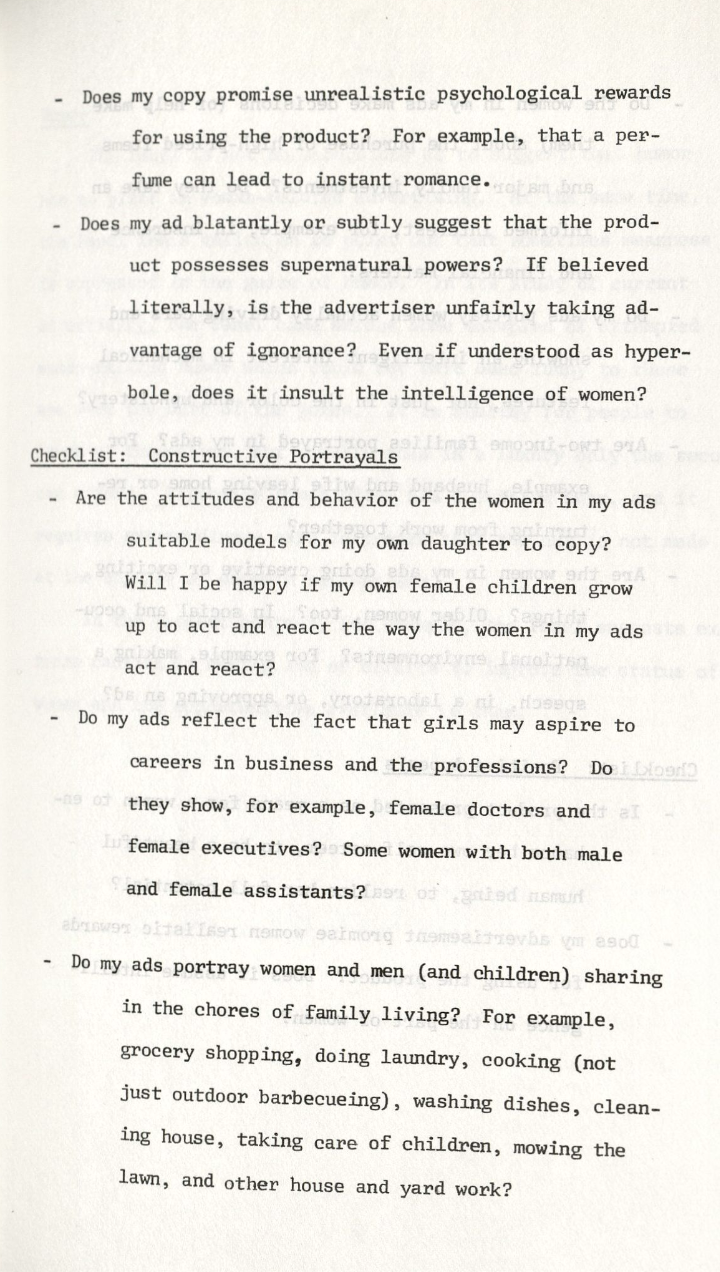

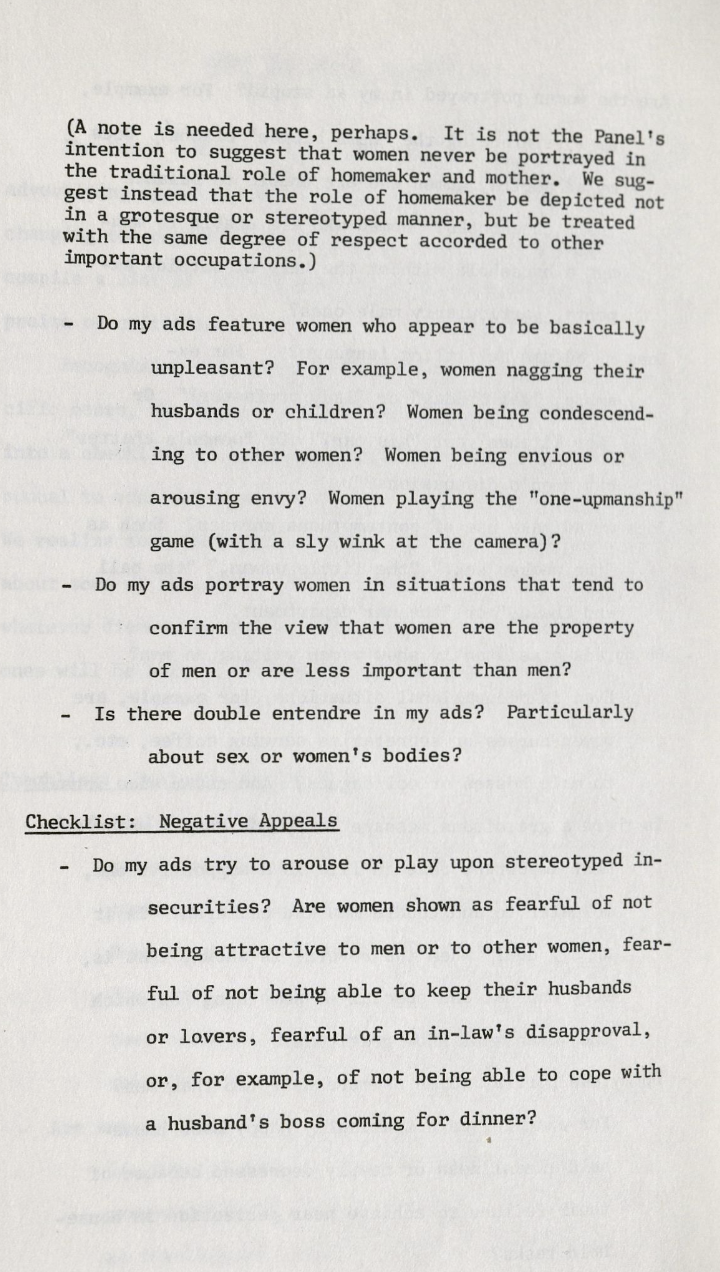

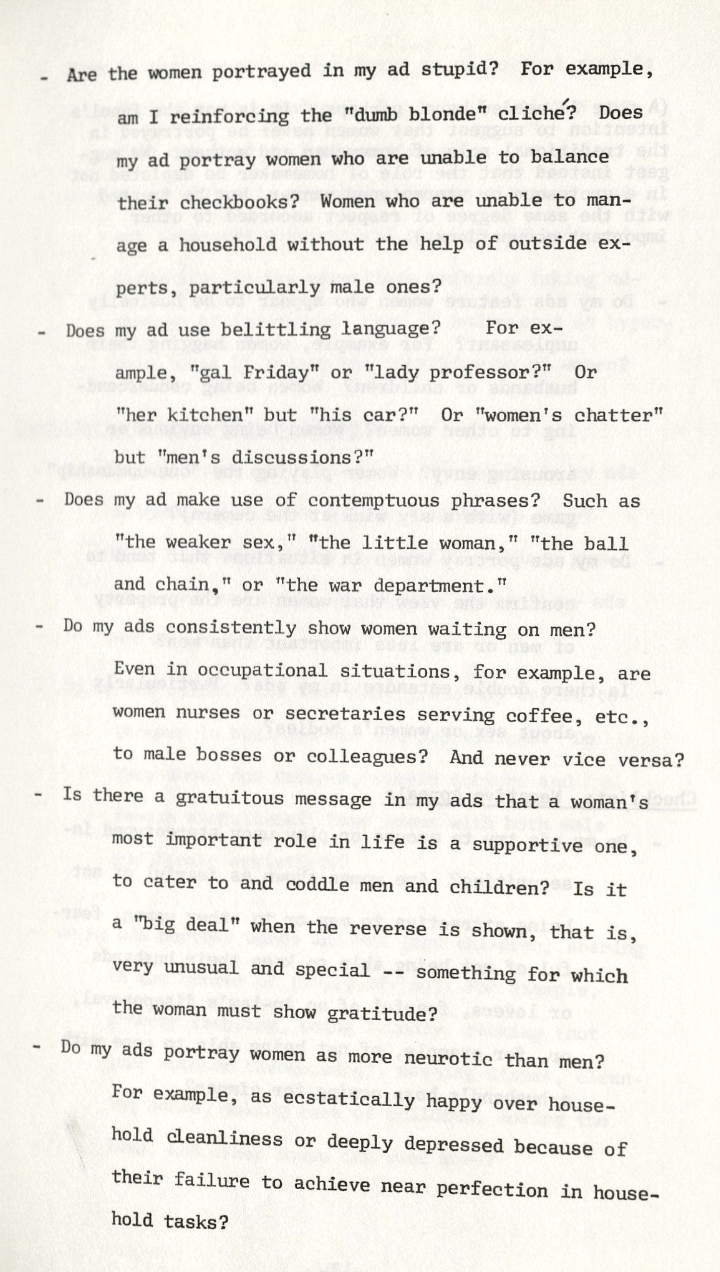

In order to avoid offensive advertising, the panel proposed a checklist of questions for advertisers to keep in mind. Advertisers were urged to consider everything from, “Are the women in my ad portrayed as stupid?” and “Do my ads reflect the fact that girls may aspire to careers in businesses and the professions?” to “Do my ads portray women actually driving cars?”

Take a look at the full checklist from the NARB report:

Source: Advertising and Women, 1975