The relationship between feminist movements and the advertising industry is one of contention, criticism, and, sometimes, cooperation. We had the opportunity to interview two women who have worked extensively with advertisements since the 1960’s, and whose professional work is included in the exhibits of this project: Dr. Jean Kilbourne and Caroline Bien.

The Jean Kilbourne Papers and the Caroline Bien Papers are housed in the Rubenstein Library.

Jean Kilbourne

Dr. Jean Kilbourne is a media critic who explores depictions of women in advertisements and the underestimated impact those ads have on feminist concerns such as violence against women, equal distribution of care work, and the commodification of feminism by corporations.

Caroline Bien worked as a copywriter and upper level executive at a number of prestigious ad agencies, including Warwick & Legler, D’Arcy MacManus & Masius/deGarmo and Grey Advertising. Many of her ad campaigns targeted women with products such as lingerie, douches, makeup, and clothing.

Kilbourne and Bien had different relationships with the advertising industry. They both agree that sexism was rampant, both in the ads themselves and in the masculine work environment of advertising agencies.

While working as a secretary for a medical journal in the the late 1960s, Kilbourne was struck by the “demeaning” advertisements for women’s products, such as birth control, and began to collect and analyze other advertisements she found to be problematic and offensive.

Meanwhile, Caroline Bien was creating advertisements that effectively sold similar products to women, sometimes a difficult task as her bosses would veto more empowering ads and put limitations on her work. Like other women in the advertising industry, she faced sexism in the day-to-day by male colleagues who sometimes took her ideas and did not include her in certain meetings.

Kilbourne found that convincing other feminists that advertisements were a serious problem was harder than expected. “People would say things to me like ‘Oh, well, we’ve got serious issues to deal with,’ such as violence against women, you know, not the image of women in advertising, which is more trivial. My response is that it’s related. The fact that we are surrounded by these images, the objectification of women, actually sets us up for violence and abuse.”

“People would say things to me like ‘Oh, well, we’ve got serious issues to deal with,’ such as violence against women, you know, not the image of women in advertising, which is more trivial. My response is that it’s related. The fact that we are surrounded by these images, the objectification of women, actually sets us up for violence and abuse.”

As Kilbourne convinced other feminist scholars of the importance of her work, she recognized there were different strategies, politics, and tensions among various feminist theoretical frameworks. “At that time, there was a split between what we call the radical feminists and the more liberal feminists,” she noted. On one hand, “there were the radical feminists who felt sexism was at the root… that it was all related to social justice and we were wanting to change the system,” while “the more liberal feminists wanted more women to be able to go into the ad industry or law school, but not necessarily change the system.”

As a women in the ad industry, Bien was well aware of the changes and differences between women’s attitudes in the 1950’s and in the 1960’s, as “women were feeling their first bursts of freedom, just to be liberated from your garter belt and nylons was something,” she noted.

Of course, companies and advertisements began to pick up on these changes and cater towards “The New Woman.” But adjustments to sexist or misogynistic ad campaigns, according to Kilbourne, “really wasn’t going to change anything, it was just going to make it easier for advertisers to target women.”

Kilbourne and Bien both emphasized that the issue of empowering women in advertisements is more complicated than it seems. For one, there are no regulatory authorities in the United States that monitor the “public health issues” of advertising, as Kilbourne put it, that could change the system from the outside.

Furthermore, obstacles facing women working in the advertising industry itself were and are formidable. Bien got a job in fashion advertising because, well, “That’s where they put women. You could get a job in cosmetics and fashion. The men let you have those jobs. Unless you were in an agency that was dominated by cosmetics or fashion, you were often marginalized.” “When ‘the boys’ failed to deliver on creative,” Bien continued, “they would say let’s give it to ‘the girls’ to see what they can do.”

Kilbourne recognizes the role of women in the industry “who were interested in real change – but tended not to have a lot of power.”

Bien and Kilbourne both clearly articulate how the advertising industry has co-opted feminist movements since the 1960s in order to sell more products to women, but emphasized, once again, that the results of co-opting progressive movements are more complicated than they might seem. “I don’t think advertising is at the leading edge of change,” Bien noted, but it does, however, have the potential to “popularize” feminism and “make it acceptable for the mainstream.”

Bien viewed co-opting the women’s liberation movement as an inevitable part of the advertising process, “Speaking as a creative, I don’t think we cynically ‘co-opted’ or exploited liberation. We were simply using the language of our time. Being aware of the zeitgeist is what the job was about. We were giddy about the possibilities for women. Ads reflected that. Advertising is a business, and that business exists to sell stuff. Did we always get it right? No. But we tried to get it better.” “Advertising has the potential to de-fangs things…. It makes it acceptable,” she added.

“Advertising has the potential to de-fangs things…. It makes it acceptable.”

While feminists in the movement pushed for policy change and fought against gender inequality, advertisers applied the idea of freedom to lighter makeup and less constrictive undergarments such as “liberating lingerie.” However, in order to ‘de-fang’ the Women’s Liberation movement, many of the same, harmful stereotypes persisted.

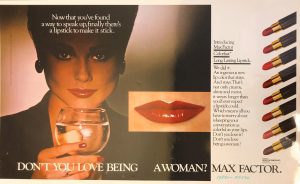

Kilbourne explained how there was a lot of fear that “women finding a way to speak up [was] going to somehow de-feminize them or make them no longer appealing or desirable to men.” Part of the backlash against feminism, she continued, was the perception “that feminists were man-haters and didn’t shave our legs and didn’t wear lipstick.”

Advertisers combated these fears by presenting a version of feminism that aligned with the accepted societal standards of beauty. As Kilbourne puts it, “this was an attempt on the part of advertisers to try to exploit the goals of the movement and use a very stereotypical image of the woman to say you can still be the stereotype.”

“You can still be the stereotype.”

Max Factor, 1979

One of the feminist tropes that emerged out of ad agencies was what Kilbourne calls the “superwoman.” The “superwoman” was an image of a woman who could do everything; successful in her career, conventionally beautiful, a devoted mother, and a seductive wife. She was typified by the Enjoli perfume ad, which bore the copy, “You can bring home the bacon and fry it up in a pan, and never let him forget he’s a man.” Kilbourne explained that this new stereotype was actually counterproductive because it “added to the stress women felt, and normalized that women were supposed to do this effortlessly without any help from their partners or, god forbid, the government.”

Enjoli, 1980

So while women were represented in more professional roles in advertisements, the underlying notion that a woman’s role was ultimately to be a mother to her children and a sex object for her husband remained.

Another issue that Kilbourne raised is the fact that advertising promotes products as the solution to our problems. Instead of addressing underlying inequities and entrenched/institutionalized sexism through public policy, advertising promotes the idea that liberation can be achieved through buying the right products. “We are constantly getting the message that it’s up to us; if we’re not succeeding it’s our own fault, and if we just get the right mascara everything will work out,” says Kilbourne.

Bien agreed with the underlying consumerism of advertising culture: “It sells it; it sells things. I mean that’s what they’re in business to do. That’s it. You’re selling things; you’re selling ideas. Stuff. Stuff.”

When asked about today’s advertising industry, Kilbourne and Bien had mixed feelings. When asked about advertisements like Dove’s representation of diverse body types and the Always ‘Like a Girl’ campaign, Kilbourne described it as “tricky.”

Always, 2014

Dove, 2014

She acknowledged that some feminists criticize these ads for not making a difference and for being focused solely on public relations or scoring points, still, she says others feel that “It’s good to have something that looks like a counter ad out there. Something that at least brings it into the public view and creates dialogue.”

Kilbourne went on to say, “Even if the motives for advertisers are not perfectly pure […] what I care about is that we get these alternative images out there and that more and more people see them, […] because there is so little out there that does give any kind of opposite message or a different message. At this point I’ll settle for whatever I can get.”

Bien also seemed torn on the issue. When first asked about the changes that have taken place in the industry since her retirement in 2006, Bien was skeptical of the intentions behind recent socially progressive ad campaigns. Bien described certain companies as “feeling very smug and self satisfied” for promoting diversity in advertisements, specifically when brands showcase different body types of women.

Despite this critique, Bien ultimately acknowledged that more diverse representation can pave the way to change and can be beneficial in making representation acceptable. As she emphasized earlier in our discussion, advertisements make change palatable (and hopefully, profitable).

With the creation of more advertising campaigns that provide an alternate image, Bien says “I feel like it’s better because your eye gets used to it. […] And that’s good, your eye needs to get used to things, and when your eye gets used to things you accept them.” “I’ve never felt advertising is the all-powerful big brother looming over us all it’s often portrayed to be,” Bien added, “it’s filled with hits and misses, courage and cowardice, insecurities and bombast.”

Considering the ubiquity of advertisements in our daily life, we asked how we should approach and engage with the advertisements we see. “All ads are selling products, and we all use products,” Kilbourne said. One of her suggestion is to purchase from brands that align with your values. Echoing Kilbourne, Bien adds that “when all is said and done, the consumer rules!”

On how we, as consumers, can make a difference, Kilbourne promoted media literacy among other strategies. Kilbourne believes that teaching individuals how to be critical of ads and of the media as a whole is one way to truly make change. “Media literate people would demand better,” she states.

A key tenant of media literacy is recognizing the power that advertisements have. “We have to confront the most egregious examples and call them out, but mostly keep trying to understand that these images actually do affect us.” One of the main reasons why advertisers maintain power over us, Kilbourne claims, is that “as long as we feel superior to ads because we think we’re too smart to be influenced, we are actually much more susceptible to them.”