“The new woman–that’s a catchy phrase to throw around. Does she really exist? Or is she just a slick slogan dreamed up by an overeager Madison Ave. copy-writer? I’m here to tell you–she is real, all right, and multiplying. Who is she?”

–Tina Santi, Corporate VP Colgate Palmolive, 1979

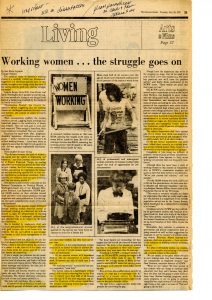

In the mid-70s, Madison Avenue had traded in their housewife stereotype for a new one: “the new woman.” However, like all stereotypes, the working woman on the pages of glossy magazine ads, was a fantasy. These elegant, empowered “superwomen” dreamed up by advertisers would lead you to believe that the average American working woman in the mid-twentieth century had suddenly achieved equal status in the workplace and was now enjoying a high-paying job in some respectable middle-management or executive role. Images of this “new woman” in the media perpetuated an illusion of empowerment and progress. While women had joined the workforce in large numbers, they would be disappointed to find that they faced much of the same discrimination in the workplace as they did at home. So who was this mythical “new woman” really?

Limited Positions

This is what advertisers would have you believe about working women in the 70s:

“Astute marketers are beginning to discover that women have opened the doors to unlimited professional careers, too. You now see them in the courtroom–in the operating room—building bridges—running cities—you see them as computer sales experts—wall st. wizards—advertising and public relations executives.”

–Tina Santi, Corporate VP Colgate Palmolive, 1979

While this image of women breaking into a wide variety of highly-skilled, high-power positions in industries certainly made for compelling marketing, the overwhelming truth was that the majority of women were ushered into low-skilled, low-paying jobs with little opportunity for upward mobility. In 1973, the same year as the debut of the Charlie Perfume ads, only 15% of all women in the workforce occupied “professional” or “technical” roles. While more women had started working, the number of women in “privileged occupations” had actually decreased since 1940 (American Women: Their Use and Abuse, 1969).

The majority of women worked as, you guessed it, secretaries. By far the largest classification of women workers was “clerical,” with women representing 75% of all secretaries and bookkeepers in the US. Women also worked in large numbers in the service sector, and other low-skilled jobs. Education attainment made little difference, as judge Shirley Chisholm explained,

“When a young woman graduates from college and starts looking for a job, she is likely to have a frustrating and even demeaning experience ahead of her. If she walks into an office for an interview, the first question she will be asked is, ‘do you type?’”

-Hon. Shirley Chisholm, 1969

Wives and Sex Objects in the Workplace

“Here is the ultimate dehumanization since, as subordinates, women are conditioned to act out the expected role-relationship. Men expect women to assume traditional husband-wife roles on a psychological level. The woman must embellish, enhance, satisfy and fulfill the ego needs of her ‘superiors.'”

-Dr. Judith Fabian, 1972

These supporting roles that women played as secretary, nurse, waiter, etc. were in a sense mere extensions of the roles they played in the home. As the office wife, she was assigned to what many called the “go-fer” role: completing menial tasks like getting coffee and cigarettes or arranging their bosses’ personal engagements, like their doctors appointments (Time, 1972). Women in the workplace were never allowed to forget their place as sexual objects. From being addressed as “dear” and “honey” to being invited to “show their wares” at an office “hot pants” party, the working woman was frequently reminded that she was a sexual object (Special Issue: The American Woman, 1972). Exaggerated examples of this sexy secretary stereotype could be found in 70s erotic novels, like the 1954 Huckster’s Women, captioned: “meet the ambition-driven career vixens of ad alley, who would sell anything to get ahead.”

- Charm and Poise for Getting Ahead, 1969

- Huckster’s Women, 1954

Prescriptive literature coached women on how to dress and behave for success in the workplace– the underlying message being that her ability to please her male supervisors with her looks and pleasant personality was just as important to her success as her actual ability to do her job. While these books did not encourage ambitious workers to dress like the office tart or sleep their way to the top, they were clear that appearance “[was] extremely important in the modern world” (Charm and Poise for Getting Ahead, 1969).

“A pretty face and a curvaceous figure may be successful in attracting male attention, but they won’t get the work done.”

-Charm and Poise for Getting Ahead, 1969

Any attempts to resist these gender stereotypes by adopting an aggressive demeanor or a sloppy approach to personal grooming were not encouraged.

Unskilled Jobs Mean Unequal Wages

“The advertising strategy for many companies and agencies often reflects the lifestyles of their executives.”

-Faith Popcorn, president of BrainReserve, 1985

Since the majority of working women were not working in high-paying, executive positions, very few actually lived the glamorous, moneyed lifestyles of the advertising executives who dreamed up the “new woman.” Most women worked out of economic necessity. Only 20% of women had enough money to work purely for “self-fulfillment,” whereas 40% of women worked to make ends meet (Training a Woman to Know her Place, 1973). The poorest women, who were predominantly women of color, made up half of all domestic workers in 1970 (Minority Wages Factsheet, 1973). These women often worked for less than minimum wage.

“Women are in the crap jobs of society. Five and one-half million women are among the workers still unprotected by the federal minimum wage standards, like cooks and maids.”-Lyn Wells, 1969

The fact that most women were relegated to low-skilled jobs contributed to an increasing wage gap. In fact, the wage gap was larger in 1970 than it was in 1955 (US Department of Labor and Employment Standards Administration, “Earnings Gap Factsheet”). By 1970, women with a minimum of five years of college education, on the average, only made 65% of what college-educated men earned. For women with only grade school and some high school education, that figure was closer to 55% (Earnings Gap Factsheet, 1970).

ALFA Archive, Box 12

Discrimination in the Workplace

Deeply ingrained beliefs about the competencies of women as workers informed discriminatory policies that disadvantaged women in the workplace. The stereotype that women were weak and temperamental domestic beings who belonged in the home, translated into widespread beliefs that women were unfit for the demands of the workplace. While statistics proved otherwise, it was not uncommon to hear that there were higher rates of absenteeism and more job turnover among female employees.

“The unspoken assumption is that women are different. They do not have the executive ability, orderly minds, stability, leadership skills, and they are too emotional.”

-Hon. Shirley Chisholm, 1969

While policies like the Equal Rights Amendment of 1972, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Equal Pay Act of 1963, and affirmative action put legal pressure on companies to improve the working conditions of their female employees, women were often still subjected to discriminatory practices, that limited their opportunities and earning potential.

Some of this gender discrimination was explicit in workplace policies and legal codes. Rules limiting the weight a woman could carry or barring them from lucrative night shifts kept the wages of women working in manufacturing jobs low and excluded them from some physically intensive jobs altogether (American Women: Their Use and Abuse, 1969). Nepotism policies in certain fields, like academia, prohibited the hiring of both members of married couples, almost always to the detriment of the wife. Pregnancy was not covered by disability compensation, forcing women to take unpaid time off and reinforcing stereotypes about women being unreliable employees. Benefits were denied to part-time workers, who were predominantly women.

Unwritten Rules of the Workplace

In some cases, token improvements brought on by mounting social and political pressure were made to discriminatory workplace policies. However, despite any “official” progress that was made, subtler forms of gender discrimination prevailed. These unwritten rules of the workplace created substantial disadvantages for female employees. Even in industries where female middle-management and executives were more common, like advertising and sales, women still experienced what copywriter Caroline Bien described as “paper cuts.” At the upper levels of the corporate ladder, female professionals were excluded from informal meetings that took place off the clock, in places traditionally reserved for men. As one female executive explained, “So much information in management is passed along informally at lunches, over drinks and at a bar after work” (Special Issue: The American Woman, 1972). Women had to work harder to receive recognition for their contributions. Bien described how:

“You would give your idea and no one would hear it, and then someone at the table who was male would give the same idea and everyone say ‘what a great idea.’”

-Caroline Bien, copywriter, 2019

In sales roles, women were relegated to selling low-ticket items like greeting cards, while men made commissions on expensive must-haves like appliances. Women in professions such as law faced harsh double standards during negations, where they were either deemed “too sweet” or “too aggressive.”

A Word About Tokenism

Of course, there were exceptions. The media loved to highlight the token female executive, lawyer, engineer or doctor; however, these women were often the product of unusual circumstances and always had to work twice as hard as any man to get where they were. As this feature on “Four Women Who Made It” from a 1972 special Time Magazine claimed: “[It] takes a prodigious effort, great motivation and many extra years for women to break into the command echelons of business. Often women have to start their own companies to get there at all.” (The New American Woman, 1972)

- Angela M. Jeannet papers, Box 2

- Angela M. Jeannet papers, Box 2