In Gill v. Whitford, twelve voter-plaintiffs challenged the Wisconsin legislature’s 2011 redistricting as a violation of Fourteenth Amendment equal protection rights and a burden on First Amendment associational rights. After a bench trial, the district court concluded that the 2011 map had the intent and unjustified effect of “plac[ing] a severe impediment on the effectiveness of the votes of individual citizens on the basis of their political affiliation,” and entered judgment in favor of plaintiffs on both constitutional claims. The trial court based its findings of discriminatory effects on a compelling and extensive record that would have withstood appellate review under the deferential standard applicable to such causal and statistical inferences.

In a recent unanimous decision, however, the Supreme Court did not reach the merits of the claims, and instead vacated the district court’s judgment on the grounds that the plaintiffs had failed to demonstrate standing to bring their case. Describing the necessary standing as limited to “voters who allege facts showing disadvantage to themselves as individuals,” the Court determined that only four of the twelve voter-plaintiffs had complained of injuries specifically stemming from the packing or cracking of their own districts, and that the case at trial had improperly focused on statewide harm. The four plaintiffs pleading individual harms will have another opportunity to advance their claims on remand.

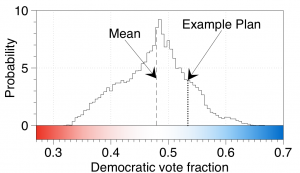

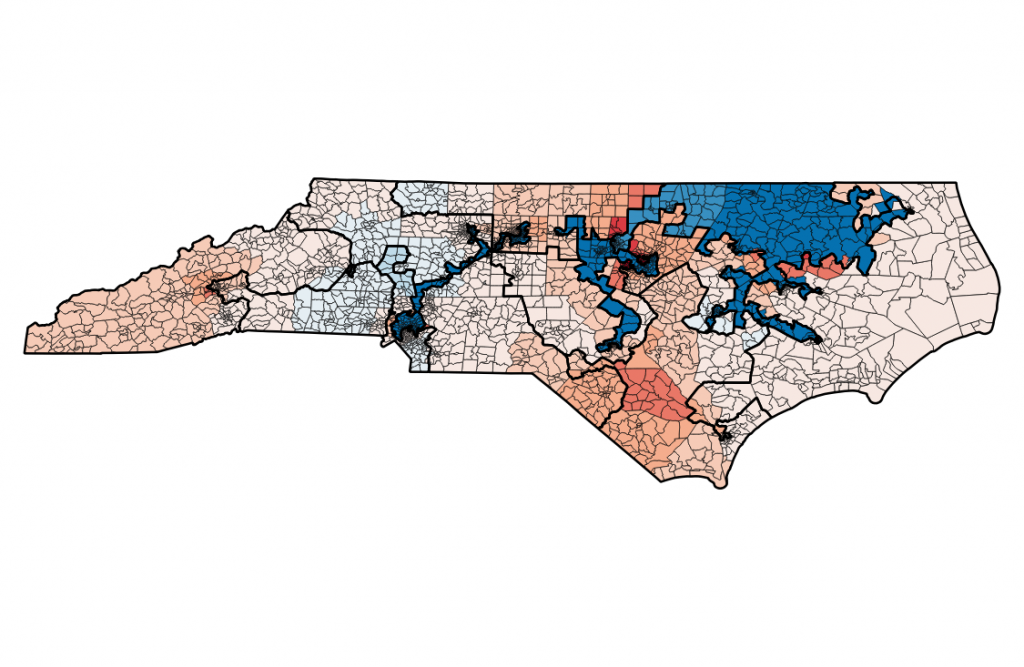

Without directly addressing the justiciability or merits of the claims, the Court noted that the plaintiffs had based their showing of statewide harms on measurements of partisan asymmetry, in accordance with the “social science tenet that maps should treat parties symmetrically.” The basic idea that courts can evaluate the severity of partisan gerrymandering in terms of “the extent to which a majority party would fare better than the minority party, should their respective shares of the vote reverse,” had been previously considered in LULAC v. Perry but found by Justice Kennedy to “shed no light on ‘how much partisan dominance is too much.’ ” The Gill plaintiffs had responded to this concern by offering the efficiency gap as a quantitative measure of partisan asymmetry, defined by political scientist Eric McGhee and legal scholar Nicholas Stephanopoulos as “the difference between the parties’ respective wasted votes in an election, divided by the total number of votes cast.” As the Court pointed out, however, a single statewide number could not describe the effects of the 2011 redistricting on individual voters in different parts of the state.

The efficiency gap has other shortcomings and peculiarities, as other commentators have pointed out. It can treat highly competitive 50-50 districts as problematic and lopsided 75-25 districts as fairly drawn, and is prone to imprecision in states having congressional delegations too small to closely reflect vote shares. It also enshrines a previously unrecognized principle that a party’s legislative majority should be twice the proportionate size of its statewide vote majority (at least when turnout is roughly uniform across districts). Continue reading “Analyzing Partisan Gerrymandering Through Geopolitical Structure After Gill”