Background: Marijuana Legalization and Perception of Risk

Marijuana is currently legal for adult recreational use in 11 states and the District of Columbia, and medical use is legal in 33 states. Canada fully legalized marijuana in 2018, and other countries are also reconsidering their marijuana laws.

A 2018 Pew Research Center poll found that approximately 62% of Americans believe that marijuana should be legalized — a new high point for polling on the issue. Legalization has grown consistently more popular since the 1990s. Survey data on drug use show that adult marijuana use in the U.S. is also increasing over time. Meanwhile, fewer people consider marijuana use to be harmful — from 2002-2014, that portion of the population shrunk from 50.4% to 33.3%.

Despite all these changes in policy and public opinion, much remains unknown about the health impacts of marijuana use. Why is science lagging behind public sentiment? One reason is a lack of consistent high quality data on use.

Data on Marijuana Use

Similar to how the U.S. Census gathers demographic information, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) collect information about public health. These nationwide surveys are often the best way to assess marijuana use on a national level and serve as the primary data source for many studies. Researchers can also learn about marijuana use habits from statewide and local surveys, including those by state health departments.

Despite these resources, information on marijuana use is often sparse, inconsistent, and incomplete. There is no standard way to ask about a person’s marijuana use habits, and marijuana use can fall into different categories, depending on who is asking. For example, NHANES and NSDUH ask questions about use patterns for “marijuana or hashish”, which are considered separate from “other street drugs.” Other surveys lump together all “illicit drug use”, including marijuana.

Response bias can also skew findings. Because marijuana (and other drugs asked about in these surveys) is still illegal at the federal level and in many states, participants may be uncomfortable answering truthfully about their habits or may skip these questions entirely. This can lead to underestimates of how many people use marijuana and how often they use. Ultimately, this limits the ability of researchers to look at marijuana use in relation to various health outcomes.

Response bias can also skew how we understand marijuana use from state to state. Respondents may be more hesitant to report use if they live in a state where it is still illegal, compared to in a state that has legalized the drug. Response bias is something that happens frequently in survey data and can be accounted for, but it usually requires more in-depth data collection than surveys alone can provide.

Beyond frequency of use, there isn’t a widely accepted or reliable way to assess the quantity or potency of marijuana an individual consumes. This means that there is no standard way to assess an individual’s “dose” of marijuana. This is especially concerning given that THC potency in marijuana has steadily risen in recent years, with one study reporting an increase from an average of 4% THC in 1995 to 12% THC in 2014. Further, marijuana products such as edibles, vape fluid, or dabs can vary widely in their THC concentrations and potentially from state to state.

Fluctuating potency, inconsistencies with marijuana terminology and classification, and reporting bias all complicate the process of quantifying the risks associated with marijuana use. Finally, because marijuana is commonly smoked, it can be difficult to separate the impacts of smoke exposure from those of the marijuana constituents that might be found in a product like vape liquid or edibles.

Establishing Causality

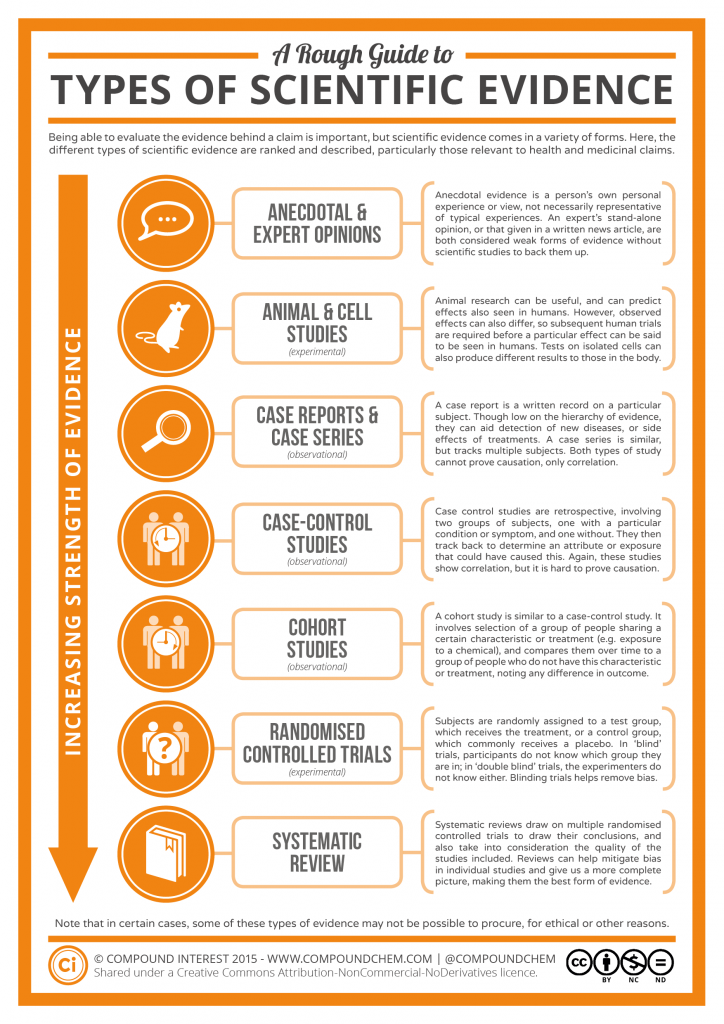

Beyond the challenges in measuring use, the legal status of marijuana makes it difficult for researchers to carry out research on potential health impacts and benefits from use, to say nothing of establishing causal links. Marijuana is still a Schedule I controlled substance as classified by the US Drug Enforcement Agency, so clinical research on marijuana is difficult to conduct.

Should marijuana become legal at the federal level, it still may take a while to gather useful findings from the expanded landscape of acceptable types of scientific research and clinical trials. However, the spread of legalization offers the chance for a number of “natural experiments” in states where legalization is implemented to evaluate the available data from an epidemiological and community health perspective. For more information, refer to the CDC’s webpage on Marijuana and Public Health.