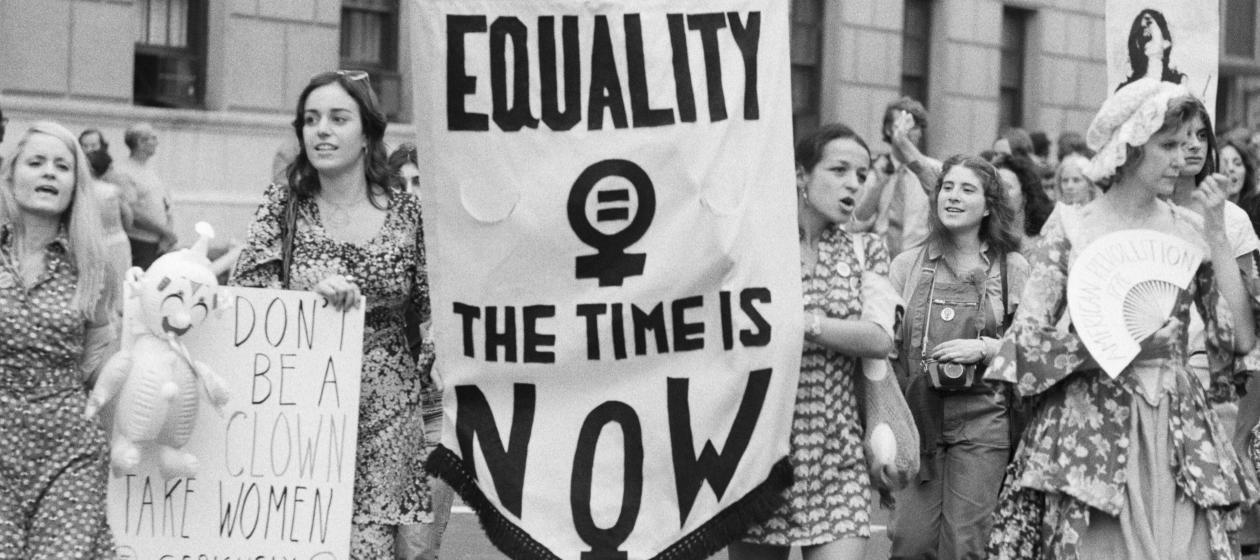

About a year ago I read Melinda Gates’s memoir, The Moment of Lift. In the book, the former Microsoft executive and Duke graduate discusses her work with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and her role as a global health advocate and leader. Gates’s work has focused on women’s empowerment, specifically concentrating on women’s health education and access to family planning in countries around the globe.

The book has definitely received plenty of flak in the past; reviewers point out some of the obvious issues with Gates’s service (i.e. she’s white and has sizable wealth and power to fuel her interests). But despite the criticism, her words really opened my eyes to a huge global issue. She hits hard on one crucial point: access to birth control is a key aspect to empowering women.

A 2012 study showed that access to the birth control pill had large economic impacts for working women, both single and partnered. It found that “early availability of the birth control pill is responsible for roughly a third of women’s wage gains since the 1960’s.” These figures are attributable to women’s ability to control when and how they have a family, giving young women more time to invest into their careers early-on. This gave them greater workplace experience and more time to dedicate to education, especially for male-dominated fields.

The Moment of Lift largely focuses on family planning outside of the United States (mostly developing countries) and draws real life examples from Melinda Gates’s international travels. However, we need to recognize that inaccessibility to family planning is not a non-issue here at home.

For one, our school systems are long overdue for an overhaul of the sex education curriculum. The facts when it comes to sex-ed in public schools are astounding. Not all states require that sex-ed be taught, and even in states that do require sex-ed, the curriculum is not mandated to be medically accurate. This means that some teens are learning incorrect information, putting them at risk for unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. Additionally, many states place the focus on abstinence-only education, circumventing conversations about safe sex practices, including contraceptive use and use of barrier protection. The result is a high rate of teen pregnancy in the U.S., the burden falling primarily on young women and their futures. Our inadequate attention to the importance of health education is certainly a barrier in access to family planning, and ultimately a barrier to women.

However the fight for increased access can’t just stop at sex education. Like many other essential drugs, birth control pills, injections, and implants fall into the hands of Big Pharma. Birth control pills aren’t sold over the counter in the U.S. and can be incredibly expensive to pay for out of pocket. This problem has only been exacerbated by the current Covid-19 pandemic. With unemployment on the rise, many women have lost health insurance benefits that pay for costly contraceptive methods. Additionally, for women who usually see a healthcare provider for contraceptive injections, insurance companies are blocking access to self-administered injections. It’s also important to note that for many women, birth control is not just used to prevent pregnancy. Many types of birth control are forms of hormone therapy to regulate the menstruation cycle or symptoms of other underlying hormonal issues. Even if not for contraceptive use, birth control is absolutely an essential item.

Finally, the great hypocrisy that affronts women’s reproductive rights in our country is that the same conservatives who will do everything in their power to overturn Roe vs. Wade, are also the ones unwilling to invest government resources into prevention and protection (sex education and affordable contraception) early-on. It’s about time that we reassess our strategy.

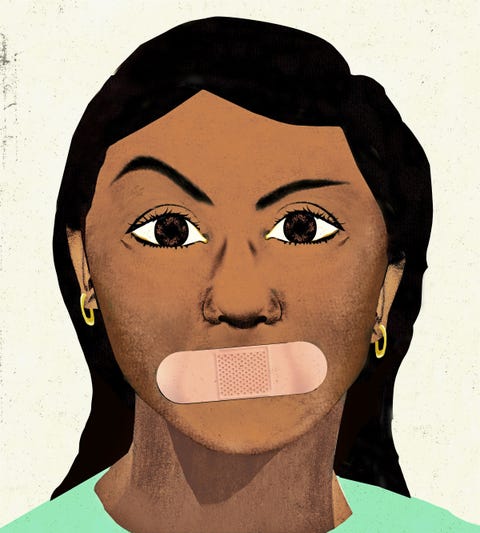

However, I’m learning that social issues occur in the grey. I’ve been able to learn about gender identity versus expression, and making spaces more inclusive for womxn. I’ve simultaneously looked at situations of social justice as multifaceted ones. I specifically looked at how women’s rights movements sometimes exclusively benefitted high-middle income white women by not addressing the intersectionality of race, class, gender expression, etc. These experiences made me look at my work as a member of on campus organizations as well as my continued work within my internship differently. As I research information to assist victims of teen dating violence, I wonder if I consider the intersectionality of victims in my research to ensure that one specific person isn’t being represented and advocated for.

However, I’m learning that social issues occur in the grey. I’ve been able to learn about gender identity versus expression, and making spaces more inclusive for womxn. I’ve simultaneously looked at situations of social justice as multifaceted ones. I specifically looked at how women’s rights movements sometimes exclusively benefitted high-middle income white women by not addressing the intersectionality of race, class, gender expression, etc. These experiences made me look at my work as a member of on campus organizations as well as my continued work within my internship differently. As I research information to assist victims of teen dating violence, I wonder if I consider the intersectionality of victims in my research to ensure that one specific person isn’t being represented and advocated for. Currently I am struggling with being a part of organizations created for change but being minimally politically involved on my part. I have the opportunity to be a part of amazing organizations unafraid to speak out against injustices and show their political activism. I have always said that I don’t see myself as a political being because I have associated politics with choosing to be republican or democratic, but I am learning that being political means making sure the social change and inclusive environments I want to promote are possible. This shift made me see that my intentions and my actions could contradict each other, and I plan on spending time researching my actions towards political activism and what that means for my future work within issues of social injustice.

Currently I am struggling with being a part of organizations created for change but being minimally politically involved on my part. I have the opportunity to be a part of amazing organizations unafraid to speak out against injustices and show their political activism. I have always said that I don’t see myself as a political being because I have associated politics with choosing to be republican or democratic, but I am learning that being political means making sure the social change and inclusive environments I want to promote are possible. This shift made me see that my intentions and my actions could contradict each other, and I plan on spending time researching my actions towards political activism and what that means for my future work within issues of social injustice.