Caution. Today there will be easy-to-confuse place names beginning with the letter T.

Though Tiumen comes before Tobolsk on the west-east route, on my trip I started with Tobolsk and worked back. Тime for a map оr two. My guess is that wordpress will delete this stolen item from the blog post, but the fanatics among you can easily find it on Wikipedia for “Siberia,” and steal it for yourselves (if you can sort of guess what it was I posted here).

Anyway, if the map does show up on your screen, you can see my route except for Tobolsk, which is up (actually downriver, but northeast) from Tiumen, and Tomsk, which is a comfortable 4-hour bus ride northeast from Novosibirsk.

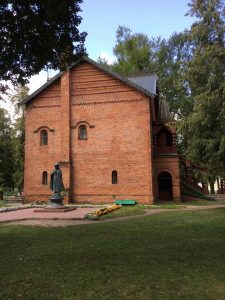

Siberian rivers flow north to the cold seas up off Russia’s northern coast. Tobolsk, the first capital of Siberia, and Tomsk, a stunning university town with extraordinary wooden architecture, are not on the main trans-Siberian railroad route but you must visit both of them.

The charm of these two towns may testify to the advantages of being off the map.

Where I am now is Tomsk, and I owe you several blog posts …I got here via Novosibirsk, formerly Novonikolaevsk, from Omsk. Are you dizzy yet? (Helpful tip: you can’t name a Soviet town after a Russian tsar). If you need something to hang on to, take a look at the (or a) map again.

About the places I’ve been there is much to report, in between epic struggles with iffy wi-fi, not to mention my cell phone, which is anal-retentive with photos and holding everything up. You may notice that this post doesn’t have a lot of images in it (yet).

Interval #1: about the cell phone:

I made my predictably regular trip to Beeline in Omsk…(btw Russian has a great word for “predictably regular”–ocherednoi)…

…where the predictably regular (ocherednaya) young lady glared at the phone, shook it a few times in the air, slapped it, and punched in a few numbers. It gave some little squeals, then fell into sullen silence. Then the Beeline girl asked for my passport and after some more jiggling around determined that my phone (and its sim card, I guess, or something) is registered not to me but to a “foreign citizen.” Which, I remind one and all, I am, but somehow not the right one. (Please don’t confiscate the phone, it’s the only minion I have. It is my traveling companion, even though it sleeps on a three-legged cot in an antechamber, gives off a smell of sour cabbage, and doesn’t always come when I call) Gentle questioning elicits the “fact” that this phone (with, I assume, all its innards) belongs to a male from Uzbekistan. See “fuzzy numbers” bit one paragraph down.

Now I do distinctly remember watching the first Beeline girl, the one in St. Petersburg, peeling the cellophane off the sim card’s packaging, taking the card out, and installing it, before my eyes, in my brand-new phone. Just saying…

And now I have the queasy feeling that I may actually be a double of, or in fact be, an Uzbek citizen who’s been masquerading my whole life as a mousey Russian literature professor from North Carolina.

All this fuzziness and liminality reminds me of another fact I learned today (the “fuzzy numbers fact” I promised). As we all know, the country code for Russian phone numbers is +7. My number, accordingly, begins with +7. But I am told that you can also dial 8 instead of +7, it’s kind of the same thing. Which plunges me into the deep black hole of Dostoevskian 2×2 = 5. If numbers are interchangeable with each other, then actually, who needs them at all?

On Thursday it will be back to Novosibirsk by bus, then overnight train to Novokuznetsk near the Kazakhstan border, and really off the map, except for what I hope proves to be an exciting Dostoevsky museum. Then back to Novosibirsk on the next overnight train, then eastward, I think next Monday or so, to Krasnoyarsk.

About my thrilling car ride to Tiumen from Tobolsk–a.k.a. short course in Russian driving habits–I will provide a complete report after I recover. But in the meantime let us appreciate Tiumen. I had five hours between my arrival here and my train’s scheduled departure for Omsk.

I sat quietly, in bliss, at a kitchen table with Alexander Medvedev and Galina, who fed me tea, caviar, and fruit and helped me mull things over. This helped me smooth my feathers, which were ruffled from the car ride. Those of us who’ve been around awhile know that it doesn’t get better than a Russian kitchen table. It’s kind of their equivalent of a trip to the spa. Alexander and Galina are specialists in Russian literature and philosophy, which adds to the excitement. Their apartment mate Sandy, who remained aloof throughout the proceedings, aroused long-dormant emotions in me, a rare combination of reverence, awe, and umilenie (the untranslatable Russian word for “tender emotion”).

It is likely he runs the place.

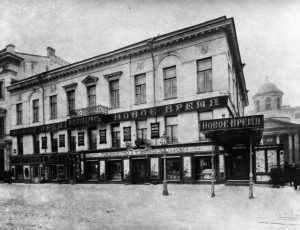

Once we have snacked and rested, Alexander walks me around town. It is a lovely evening…We begin with the appetizers, a row of photos of old Tiumen, displayed at a park at the city center:

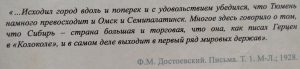

This is what the town would have looked like when Chekhov passed through in the spring of 1890, spending just one day (May 3/15). Chekhov and Dostoevsky both came through Tiumen on their way to someplace else (as I am doing). For Dostoevsky, Tiumen wins the competition between Omsk and Semipalatinsk. (More on Omsk later). One of the stands displays Dostoevsky’s famous commentary:

I walked the length and breadth of the city and arrived at the pleasant conclusion that Tiumen considerably surpasses both Omsk and Semipalatinsk. There’s a lot here that attests to Siberia’s identity as a great center of trade, and to the fact that, as Herzen wrote in The Bell, it is among the great world powers.

Though we should not forget what took Dostoevsky to Omsk and Semipalatinsk, which might well have skewed his impressions of those towns, Still, it is good to have the endorsement. And Tiumen does indeed have much to offer. Herewith, the main dish:

A freshly built promenade along the Tura River embankment, colorfully illuminated at night; a large church built more in the Kiev style than I’ve seen this time around, a monastery, beautiful old wooden houses, some flowers

(the best pictures here are the ones Alexander took)

….the Institute where Lenin’s body was kept during World War II, having been evacuated in strictest secret from his Mausoleum in Moscow

and many more interesting sights that invite one to spend more time. I also have a glimpse of the University, from outside and inside. And we pass the Post Office; here I realize what a theme post offices have become on this journey.

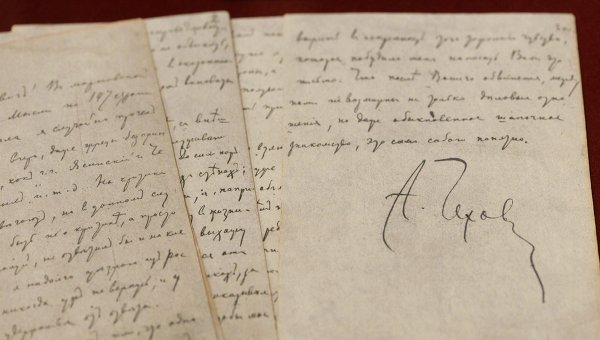

Without them, what would writers have done? And given the distances, the reliability and efficiency of the Imperial Russian postal service was remarkable. I have to keep reminding myself that this country’s territory takes up eleven time zones. Ours, by contrast, has very small hands, I mean time zones, only three (or maybe four or something, if you throw Hawaii in). Chekhov confidently sent and received money by post, not to mention other things, like, oh, masterpieces of world literature that existed in only one copy.

A vigilant reader of this blog sent me John Randolph’s wonderful article on the subject of the Russian imperial postal service:

https://www.openbookpublishers.com/htmlreader/978-1-78374-373-5/ch5.xhtml#_idTextAnchor051

Anyway, when I go to a city where Chekhov has been, I feel that whether or not there’s any evidence that he visited its post office, I like to think that he did, or walked by, or noticed it. In any case, the Tiumen Post Office deserves a shout out, this one.

It is known that Chekhov stayed one night at the Palais-Royale hotel. It stood on this spot.

The new building hosts an appealing-looking establishment, which, before I took the picture and smudged the sign, was called, uh, something like “Soleil [or something] Coffee.”

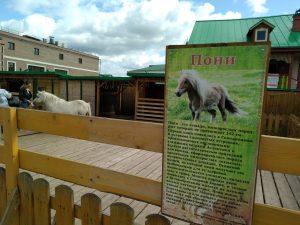

One last Chekhov thing. Readers of his letters will recall what he had to say about the sausage.

В Тюмени я купил себе на дорогу колбасы, но что за колбаса! Когда берешь кусок в рот, то во рту такой запах, как будто вошел в конюшню в тот самый момент, когда кучера снимают портянки; когда же начинаешь жевать, то такое чувство, как будто вцепился зубами в собачий хвост, опачканный в деготь. Тьфу.

In Tiumen I bought some sausage for the road, but what a sausage! When you take a bite, your mouth tastes like what you’d smell if you’d walked into a stable at the precise moment when the coachmen were taking off their foot-cloths; and when you start chewing, you get the sense that you’ve bitten into a dog’s tail that is coated in tar. Bleah.

And then “dessert”: we eat dinner! It’s pretty astonishing what you can see and do in five hours in Tiumen.

And there is still time to go back to the apartment, admire Sandy and pick up my charged devices before we head off for the midnight train. Just have to say, it’s awfully nice to be fed, entertained, taken to the train station and seen off. Makes you forget that some of this traveling can be a lonely thing.

Here are some great links Alexander sent me about Chekhov (and others) in Tiumen:

http://www.citylib-tyumen.ru/for_readers/literaturnaya-zizn/chehov/tyum_kraj

https://gorod-t.info/culture/istoriya/408/

P.S. You’re wondering about the “Vakhta”? I’ll tell you later.

…

…

What Chekhov did in Ekaterinburg is clouded in mystery. But it is good to have a sighting. Quick reminder here: I’m not traveling with a professional photographer or in fact, blog editor, translator, or trip planner.

What Chekhov did in Ekaterinburg is clouded in mystery. But it is good to have a sighting. Quick reminder here: I’m not traveling with a professional photographer or in fact, blog editor, translator, or trip planner.

OK, now I know that no one in their right mind comes to Russia for the beer. I also get that Sunday night is not when the varsity bartenders are on duty. And I know that Guiness (this is Guiness despite what it says on the class) is supposed to foam up. And maybe they think that females (or old people, or professors, or Americans, or whoever) shouldn’t be drinking beer. But honestly, is this the best they can do?

OK, now I know that no one in their right mind comes to Russia for the beer. I also get that Sunday night is not when the varsity bartenders are on duty. And I know that Guiness (this is Guiness despite what it says on the class) is supposed to foam up. And maybe they think that females (or old people, or professors, or Americans, or whoever) shouldn’t be drinking beer. But honestly, is this the best they can do?

But still: if someone had thought to wake Chekhov up, he would have gone buggy eyed, and possibly would have renounced his restrained poetics for something exuberant and decided to stay here. I admit, during my manic four days here in Kazan, the thought occurred to me. But the catch is, they don’t need a Chekhov scholar in this town. They already have one, and one of the best, Professor Lia Bushkanets of Kazan Federal University.

But still: if someone had thought to wake Chekhov up, he would have gone buggy eyed, and possibly would have renounced his restrained poetics for something exuberant and decided to stay here. I admit, during my manic four days here in Kazan, the thought occurred to me. But the catch is, they don’t need a Chekhov scholar in this town. They already have one, and one of the best, Professor Lia Bushkanets of Kazan Federal University.

And it happened in Kazan. Tolstoy “studied” Oriental languages here, then law, then off he went–but not after being incarcerated in the kartser for non-attendance of lectures. This grim place (though not as grim as where Dostoevsky would be heading in a few years) was on the second story of the hall where the university chapel was located. From outside it is down a ways, then up. Another key location in the university is what was formerly the clinic, where Tolstoy was treated for, uh…

And it happened in Kazan. Tolstoy “studied” Oriental languages here, then law, then off he went–but not after being incarcerated in the kartser for non-attendance of lectures. This grim place (though not as grim as where Dostoevsky would be heading in a few years) was on the second story of the hall where the university chapel was located. From outside it is down a ways, then up. Another key location in the university is what was formerly the clinic, where Tolstoy was treated for, uh…

.

.

There must be a story here, something Chekhovian.

There must be a story here, something Chekhovian.