Chekhov’s life journey ended on July 14/15, 1904 in Badenweiler, Germany. This turns out to be July 1/2 Old Style. Technically I should go for the “real” date but since today is JULY 1, 2022, I’m going to commit to July 1, 118 years ago today, sort of. One theme of this blog, anyway, is the fuzziness of numbers.

Chekhov came to Germany with his tuberculosis, which is what drove his trips to Western Europe in the last 7 or so years of his life. Nice, for example, for which I have been pent up with about 4 blog posts for a year now. But let’s start here, at the end. Chekhov stayed in three different hotels in Badenweiler. The first one is the Rommerbad (in a quiet revolt against the umlaut I will not go to the trouble of entering it here, or anywhere else, and will not take time for any diacritical marks, either, being American and efficient in that way). Rommerbad (“roamer bad”) is in the doghouse for all time for its treatment of the world’s greatest short-story writer and dramatist. Chekhov coughed too much and they kicked him out, as it “disturbed the other guests.” I marched to the hotel yesterday, indignant and eager to take revenge.

These are screen shots because it’s too hellish to get real photos in here (try it for 4 hours and then come back and report to me).

Now let’s get down to work. The hotel is both fancy and scuzzy at the same  time. Not knowing German is a blessing in cases like this, because the place has been renamed to something I’ll translate the “PANACEA,” which, if enter into google, gets defined as “a solution or remedy for all difficulties or diseases.” Let us ponder this. First of all, the hotel is abandoned, supposedly (again, what option do you have but to trust my German?) to be renovated:

time. Not knowing German is a blessing in cases like this, because the place has been renamed to something I’ll translate the “PANACEA,” which, if enter into google, gets defined as “a solution or remedy for all difficulties or diseases.” Let us ponder this. First of all, the hotel is abandoned, supposedly (again, what option do you have but to trust my German?) to be renovated:

The vacancy of the place, prevents me from any kind of contact with living human beings, but maybe the person who forced Chekhov to leave because his coughing was ANNOYING PEOPLE finds himself trapped in here, haunting the halls, tormented by remorse. Maybe something like widowed Olga in “The Grasshopper” (попрыгунья), who learned too late how famous her husband was.

The vacancy of the place, prevents me from any kind of contact with living human beings, but maybe the person who forced Chekhov to leave because his coughing was ANNOYING PEOPLE finds himself trapped in here, haunting the halls, tormented by remorse. Maybe something like widowed Olga in “The Grasshopper” (попрыгунья), who learned too late how famous her husband was.

Ольга Ивановна вспомнила всю свою жизнь с ним, от начала до конца, со всеми подробностями, и вдруг поняла, что это был в самом деле необыкновенный, редкий и, в сравнении с теми, кого она знала, великий человек. И вспомнив, как к нему относились ее покойный отец и все товарищи-врачи, она поняла, что все они видели в нем будущую знаменитость. Стены, потолок, лампа и ковер на полу замигали ей насмешливо, как бы желая сказать: «Прозевала! прозевала!

https://ilibrary.ru/text/706/p.8/index.html

Anyway, evicted from this monstrosity, Anton and Olga went down the hill, passing the old Roman baths on the way, and a nice little park (though in the latter case it might be is back-projected) and found themselves a room at the Friedericke, about which more in a moment.

But first let’s get artsy and do a mise-en-abyme (those who are triggered by this spelling remember, please, that I am not slowing down for diacritical marks) that will let me in past these locked doors, where I can join the souls (guilty, atoning, innocent but cast out as the case may be) haunting these halls.

Who the #$%@& would call a hotel the Panacea? (again, maybe this is not at all what the word means but hey, you don’t like it, write your own blog). Maybe someone trying to purge 118 years of guilt? Notice–not only did they kick him out but they also had the nerve to put a plaque next to the door (look up and to the right for this one, not down), expressing pride that the great man stayed here. He DID stay  there, that much is true. For an extremely short time. And they get credit for it.

there, that much is true. For an extremely short time. And they get credit for it.

Compare the beautiful etched stone sign on the balcony (to the left of the nice Chekhov wall cameo) outside Chekhov’s window on the side wall of the then Hotel Sommer, now, these days, the Klinik Park-Therme, which I deduce says “Here lived Anton Chekhov, in July 1904”

Just repeating here: “LIVED” (and then, for those concerned with precision, I actually checked this one on line, and yes, that’s what it says). Which is quite beautiful to ponder. And it was out this window that his soul flew, filling the square outside it and still living today. Which now bears his name, recognizable despite the weird German spelling:

Just repeating here: “LIVED” (and then, for those concerned with precision, I actually checked this one on line, and yes, that’s what it says). Which is quite beautiful to ponder. And it was out this window that his soul flew, filling the square outside it and still living today. Which now bears his name, recognizable despite the weird German spelling:

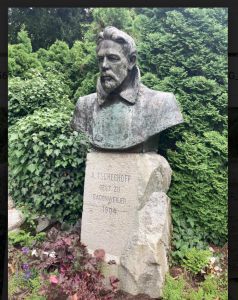

Soon there was a monument (more on this later, too), and then an actual Chekhov museum, the Chekhov Salon, and then a bronze seagull just outside his window.

Soon there was a monument (more on this later, too), and then an actual Chekhov museum, the Chekhov Salon, and then a bronze seagull just outside his window.

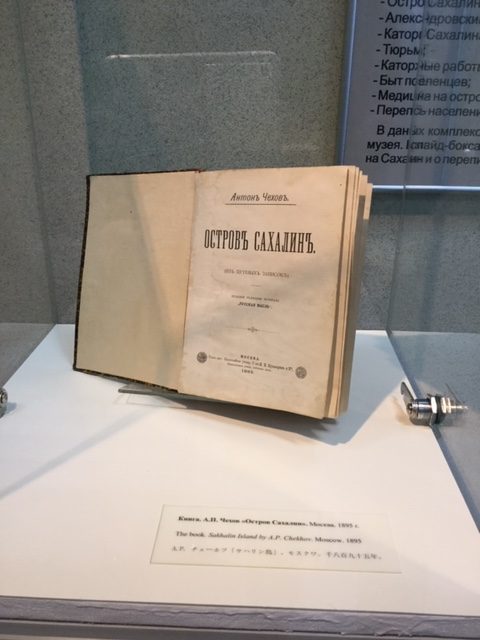

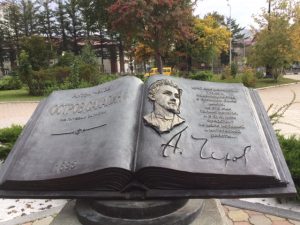

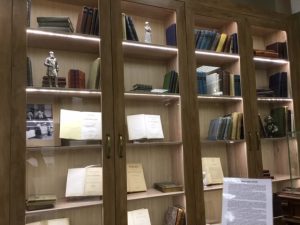

And then, the first monument, bronze, was melted down (it had to do with the war, WW I, actually, and killers needing bronze for ammunition or weapons, or whatever, or to sell; in any case this lovely little action-packed museum has an exhibit that I think is, or represents, the melted-down first Chekhov monument (deducing from the otherwise indecipherable explanation from the word Denkmal,  which I had the opportunity to learn tromping around town means “monument” and already knowing the story about it being melted down). To fill the empty place, someone made a crazy Chekhov bronze, complete with characters from his stories (look below for this one). And there’s an amazing story about ANOTHER Chekhov monument brought from SAKHALIN ISLAND here by one of the truly devoted Chekhov fans like those I have encountered on this journey, which I will tell about in the next blog post, for it is a story of heroism and martyrdom. For now, more about the museum. Somehow I thought this Tschechow Salon would be just an ordinary Literary museum with lots of writers in it, all balanced evenly, but actually this is a CHEKHOV place–with ancillary writers strewn around–Stephen Crane, some guy named Heidigger, others, too. But no doubt about it, this is his place, just one room–like him, modest, not showy, but full of content and quality. Some people planted cherry trees out front (from Taganrog, I think, so there’s a circle of birth to death, but also life being lived by the trees and by all the people walking through, and even stopping here, like me). Everything here is in German, so my brain is jumbled with it all, but the story is familiar–you can follow it in the photos displayed here, and of course because you know a lot of the story already, and supplement it by bumbling through the German inscriptions for cognates, of which there are disappointingly few. There is quite the political history here (German-Russian-Soviet-post-Soviet relations, with a conscious effort to focus on the cultural ties, which of course is also Chekhovian). It wasn’t so clear to me before in other places, but i can feel it now–that this place exists because of so many readers who appreciated Chekhov and honored him, and put in the effort to make this salon in his memory. And I am one of them too. Here is where the tears well up, because, OK, it’s Germany, he was away from home, like me, and ill, dying as everyone knew, though he carried on as though not, and all of this we behold here, the museum with its contents. And he did die here, which is why there is so much Chekhov in this town now. Otherwise, Badenweiler would have carried on its history and gone for Stephen Crane or someone more local instead. And I would never have visited. This town was for healing, though, which is what brought him here, and maybe me too. And his spirit, which flew out the window just catty-cornered to the museum, lives here.

which I had the opportunity to learn tromping around town means “monument” and already knowing the story about it being melted down). To fill the empty place, someone made a crazy Chekhov bronze, complete with characters from his stories (look below for this one). And there’s an amazing story about ANOTHER Chekhov monument brought from SAKHALIN ISLAND here by one of the truly devoted Chekhov fans like those I have encountered on this journey, which I will tell about in the next blog post, for it is a story of heroism and martyrdom. For now, more about the museum. Somehow I thought this Tschechow Salon would be just an ordinary Literary museum with lots of writers in it, all balanced evenly, but actually this is a CHEKHOV place–with ancillary writers strewn around–Stephen Crane, some guy named Heidigger, others, too. But no doubt about it, this is his place, just one room–like him, modest, not showy, but full of content and quality. Some people planted cherry trees out front (from Taganrog, I think, so there’s a circle of birth to death, but also life being lived by the trees and by all the people walking through, and even stopping here, like me). Everything here is in German, so my brain is jumbled with it all, but the story is familiar–you can follow it in the photos displayed here, and of course because you know a lot of the story already, and supplement it by bumbling through the German inscriptions for cognates, of which there are disappointingly few. There is quite the political history here (German-Russian-Soviet-post-Soviet relations, with a conscious effort to focus on the cultural ties, which of course is also Chekhovian). It wasn’t so clear to me before in other places, but i can feel it now–that this place exists because of so many readers who appreciated Chekhov and honored him, and put in the effort to make this salon in his memory. And I am one of them too. Here is where the tears well up, because, OK, it’s Germany, he was away from home, like me, and ill, dying as everyone knew, though he carried on as though not, and all of this we behold here, the museum with its contents. And he did die here, which is why there is so much Chekhov in this town now. Otherwise, Badenweiler would have carried on its history and gone for Stephen Crane or someone more local instead. And I would never have visited. This town was for healing, though, which is what brought him here, and maybe me too. And his spirit, which flew out the window just catty-cornered to the museum, lives here.

Now, just in case you’re disoriented, all the above is ONE Chekhov statue:

The face is gnarly because those are Chekhov characters in there. The statue stands just inside the doorway of the Tschechow Salon.

In my world these photos are familiar, but I have never seen them exhibited this way, from young Anton at the upper left, as at the beginning of a story, to the last Chekhov on the lower right. This fills one wall of the Chekhov Salon.

So now for a quick dip into the Hotel Sommer, aka Klinik Park-Therme. It’s an actual clinic, with a front door and a back door, both of which I try.

The back door (the one on the right) goes in from the little courtyard and must be the service entrance. I go around to the front door, slip on my COVID mask, for this is a clinic, and walk boldly up to the front desk, which is quite indistinguishable from a hotel reception desk, which I guess at one time it was. My German (non-existent) is a handicap, but eventually I am kicked up to a higher-level administrator, a bespectacled man, who is extremely kind and conscientious with his own rudimentary Engish-German mix. I feel the tender presence of a health-care professional. We discuss in our primitive manner Chekhov’s stay here, and whether his room can be visited, which of course it can’t, because, I am delighted and moved to learn, there are patients staying there, for this is a working clinic, whose task is healing. Do these patients know they are in Chekhov’s room? Does it matter? I am happy not to go in there, as this is itself Chekhovian in spirit–of course people come here to get well! The man tells me people come to this place and stay three weeks for rest and care. The place does not look like a clinic to me, with harsh flourescient American lights, a stark medicinal feel, sharp divisions between the sick and the well. It feels like a hotel, a place where you might go for some quiet time and vacation (if you are an older person and do not have to take your kids to mini-golf). This is a place for people, and if I were to be sick, I would beg to be brought here where I could rest, in Chekhov’s invisible room.

And now the middle place. When Chekhov and Olga left the odious Rommerbad, they alit in the Friedericke, which was later to be renamed the Park Hotel & Spa Katharina (https://www.parkhotelkatharina.de/en/hotel/history). This is the one Chekhov hotel in Badenweiler (of the three) where you can actually stay. So I did, as a required part of my pilgrimage, and not because the hotel has four stars (I have never stayed in a four-star hotel before, but duty called). The place is completely renovated so no living person can possibly know what room Olga and Anton stayed in. I’ll assume it was not too high up, so have chosen to sit for a whie in the main floor sitting room, blessedly empty today except for me and Chekhov, and looking out onto the astonishing sunsets of Badenweiler.  The internet is better here too. This afternoon I made an inquiry at the front desk, something quite banal about a towel, but in the process I realized I could ask about Chekhov’s room. So I flashed the blog, which brought on an administrator (the inquiry, not the blog). It turns out that she is Russian, and not only Russian, but a former MGU Philosophy professor, and we immediately tumble into Russian. After solving my banal towel problem we babble on about many Russian matters, from Chekhov to tragic world events, and she informs me that Chekhov left here because it was boring (as he wrote in a letter. If this blog were more scholarly I’d quote the letter here and maybe I will, later). In any case, this hotel was also renovated, but it has real people in it, mixed in with the ghosts. And here, as in all the Chekhov places, there are bits of him in the air–which is very very good for breathing, I have had some time to learn. There’s even an INHALATORIUM in town,

The internet is better here too. This afternoon I made an inquiry at the front desk, something quite banal about a towel, but in the process I realized I could ask about Chekhov’s room. So I flashed the blog, which brought on an administrator (the inquiry, not the blog). It turns out that she is Russian, and not only Russian, but a former MGU Philosophy professor, and we immediately tumble into Russian. After solving my banal towel problem we babble on about many Russian matters, from Chekhov to tragic world events, and she informs me that Chekhov left here because it was boring (as he wrote in a letter. If this blog were more scholarly I’d quote the letter here and maybe I will, later). In any case, this hotel was also renovated, but it has real people in it, mixed in with the ghosts. And here, as in all the Chekhov places, there are bits of him in the air–which is very very good for breathing, I have had some time to learn. There’s even an INHALATORIUM in town,

which I went in but still haven’t figured out what it actually is. Indeed this week I have thought of breathing quite a bit, knowing how hard it was for Chekhov to do, so much so that he came here. In this air, the conversation with the hotel administrators had the feel of something that could go on and on, and it turns out, the other hotel administrator, who is at the front desk and checked me in a few days ago, ALSO is fluent in Russian (being from Bulgaria), and if I had known this before, we would certainly have bonded. Things could have gotten quite intense, but new guests came to register (it is Friday, after all, the weekend is about to begin), and all three of us went back to our day jobs.

p.s. little touch of home: bikers in Badenweier

called the Switzerland (subsequently called Albergotto), in room #20 on the 3d floor. The place is now called the “Room Mate Isabella” and Florence has plaqued the fact that George Eliot stayed here at some point (at the front door’s upper left).

called the Switzerland (subsequently called Albergotto), in room #20 on the 3d floor. The place is now called the “Room Mate Isabella” and Florence has plaqued the fact that George Eliot stayed here at some point (at the front door’s upper left). No sign of Dostoevsky, though, except in one’s mind (though not the mind of the nice, tired-looking reception man, and, I gather, those of most of the hotel guests). The location is quite fancy, on a street lined with Gucci and suchlike. Post-COVID tourism has returned to Florence and one feels that the tourists are besieging the hotel people. I am no exception. But the nice lobby man perked up in a decorous professional manner when

No sign of Dostoevsky, though, except in one’s mind (though not the mind of the nice, tired-looking reception man, and, I gather, those of most of the hotel guests). The location is quite fancy, on a street lined with Gucci and suchlike. Post-COVID tourism has returned to Florence and one feels that the tourists are besieging the hotel people. I am no exception. But the nice lobby man perked up in a decorous professional manner when  I mentioned a famous Russian writer, and he showed me the sitting room and even took my photo there. As for where Dostoevsky stayed, it is daunting to track down the exact room, so I photographed a dark-looking door in Dostoevskian St. Petersburg yellow. The lo

I mentioned a famous Russian writer, and he showed me the sitting room and even took my photo there. As for where Dostoevsky stayed, it is daunting to track down the exact room, so I photographed a dark-looking door in Dostoevskian St. Petersburg yellow. The lo

bby is, or feels like, three stories up, and the room is thereabouts, so the

bby is, or feels like, three stories up, and the room is thereabouts, so the re’s a bit of plausibility. Though this could also be George Eliot’s room, or that of some other writer who was never discovered. Maybe there’s one in there now. Also relevant is a steep stairway leading down to the street. Along the way, if you are lucky, you may catch a glimpse of the lower half of a horse-carriage out the stairwell’s circular window and you might, oh so briefly, blessedly, forget what century this is.

re’s a bit of plausibility. Though this could also be George Eliot’s room, or that of some other writer who was never discovered. Maybe there’s one in there now. Also relevant is a steep stairway leading down to the street. Along the way, if you are lucky, you may catch a glimpse of the lower half of a horse-carriage out the stairwell’s circular window and you might, oh so briefly, blessedly, forget what century this is.

l existed. It became a goal of mine to buy a pen and some paper there. A very tasteful website pops right up, Giannini Firenze 1856. with the necessary, matching shop name and address, No. 22. But despite pacing and peering (oddly) into windows, there was no stationery establishment in sight. Instead, a lovely little shop offering handcrafted items made in Florence (the things that sort of look like soccer balls are actually paper globes you can stick red pins in to show where you’ve been). In conversation with a perky young English-speaking clerk I learn that the shop has only been open 1 1/2 months, and before that, there was a stationery store there. So I bought a bookmark and a small Florence homemade craft item instead. The stationery shop was in business 160 years, right up to this summer. I did breathe some of its air.

l existed. It became a goal of mine to buy a pen and some paper there. A very tasteful website pops right up, Giannini Firenze 1856. with the necessary, matching shop name and address, No. 22. But despite pacing and peering (oddly) into windows, there was no stationery establishment in sight. Instead, a lovely little shop offering handcrafted items made in Florence (the things that sort of look like soccer balls are actually paper globes you can stick red pins in to show where you’ve been). In conversation with a perky young English-speaking clerk I learn that the shop has only been open 1 1/2 months, and before that, there was a stationery store there. So I bought a bookmark and a small Florence homemade craft item instead. The stationery shop was in business 160 years, right up to this summer. I did breathe some of its air.

ual, the “check in the mail,” in the spring of 1869 they had move

ual, the “check in the mail,” in the spring of 1869 they had move to less expensive lodgings, off the Mercato Nuovo (aka Mercato del Porcellino) for what would be a stifling hot summer, before they were finally able to leave August 3 for Dresden. Piazza del Mercato Nuovo is actually very close to the Room Mate Isabella, but it has a more Dostoevskian feel to it, by which I mean bustling and chaotic, with an admixture of grime. I can also attest that it is extremely hot in July.

to less expensive lodgings, off the Mercato Nuovo (aka Mercato del Porcellino) for what would be a stifling hot summer, before they were finally able to leave August 3 for Dresden. Piazza del Mercato Nuovo is actually very close to the Room Mate Isabella, but it has a more Dostoevskian feel to it, by which I mean bustling and chaotic, with an admixture of grime. I can also attest that it is extremely hot in July.

In my line of work, everything starts to feel like a metaphor eventually. The ball and chain–that’s an easy one. Stand there quietly for a while, and you might hear a faint buzzing sound. Look up, and between Dostoevsky’s upraised collar and his bearded cheek, you will see a small, busy hornets’ nest. But what could it mean? I wish there was someone here for me to ask, but, as is often the case, it’s just me and Fedor Mikhailovich.

In my line of work, everything starts to feel like a metaphor eventually. The ball and chain–that’s an easy one. Stand there quietly for a while, and you might hear a faint buzzing sound. Look up, and between Dostoevsky’s upraised collar and his bearded cheek, you will see a small, busy hornets’ nest. But what could it mean? I wish there was someone here for me to ask, but, as is often the case, it’s just me and Fedor Mikhailovich.

It’s Dostoevsky time again. Given what has happened in the world since Dostoevsky’s 200th birthday (November 11, 2021), it has been nearly impossible for me to focus in on this footsteps pilgrimage. How can I just keep hopping merrily from one effete place to the next, jotting down petty little notes about distant, dead writers, when their country is brutalizing its neighbor, indiscriminately murdering its weakest individuals (yes, children, mothers, including pregnant ones, the aged and sick) along with their homes, in plain sight? The evil of the invasion has paralyzed me, making the COVID pandemic, in retrospect, feel like a fun adventure. And some people are actually blaming Dostoevsky.

It’s Dostoevsky time again. Given what has happened in the world since Dostoevsky’s 200th birthday (November 11, 2021), it has been nearly impossible for me to focus in on this footsteps pilgrimage. How can I just keep hopping merrily from one effete place to the next, jotting down petty little notes about distant, dead writers, when their country is brutalizing its neighbor, indiscriminately murdering its weakest individuals (yes, children, mothers, including pregnant ones, the aged and sick) along with their homes, in plain sight? The evil of the invasion has paralyzed me, making the COVID pandemic, in retrospect, feel like a fun adventure. And some people are actually blaming Dostoevsky.

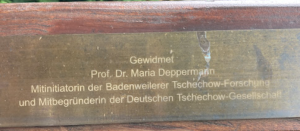

(for details, scoot down a couple of posts). Having recently visited this museum I felt personally invested in the story. Some time after 1985, Miromanov promised Badenweiler that he would give the city a new monument by 1990 in time for the 130th anniversary of Chekhov’s birth. Considering that there are at least nine time zones difference between the two locations, not to mention 7374.557584 miles (11,868 .2 kilometers), plus, inevitably, such factors as world politics and money, this would seem to be a difficult promise to keep. And yet, as the brochure reports, in the fall of 1990 Mironamov, together with his son and the sculptor Vladimir Chebotaryov,

(for details, scoot down a couple of posts). Having recently visited this museum I felt personally invested in the story. Some time after 1985, Miromanov promised Badenweiler that he would give the city a new monument by 1990 in time for the 130th anniversary of Chekhov’s birth. Considering that there are at least nine time zones difference between the two locations, not to mention 7374.557584 miles (11,868 .2 kilometers), plus, inevitably, such factors as world politics and money, this would seem to be a difficult promise to keep. And yet, as the brochure reports, in the fall of 1990 Mironamov, together with his son and the sculptor Vladimir Chebotaryov,

.

.

breath–respiration, for which we are particularly grateful on this stop on our journey, and its place as the origin of art–inspiration, and, we hope, of healing. In addition to the monuments in stone and bronze, in photographs and street-and-square names, Badenweiler also offers up a monument in spirits, a Tschechow wine, a gentle red, with which you can nurture your own on the Katharina terrace, upon your descent from the hill to dry land .

breath–respiration, for which we are particularly grateful on this stop on our journey, and its place as the origin of art–inspiration, and, we hope, of healing. In addition to the monuments in stone and bronze, in photographs and street-and-square names, Badenweiler also offers up a monument in spirits, a Tschechow wine, a gentle red, with which you can nurture your own on the Katharina terrace, upon your descent from the hill to dry land .

time. Not knowing German is a blessing in cases like this, because the place has been renamed to something I’ll translate the “PANACEA,” which, if enter into google, gets defined as “a solution or remedy for all difficulties or diseases.” Let us ponder this. First of all, the hotel is abandoned, supposedly (again, what option do you have but to trust my German?) to be renovated:

time. Not knowing German is a blessing in cases like this, because the place has been renamed to something I’ll translate the “PANACEA,” which, if enter into google, gets defined as “a solution or remedy for all difficulties or diseases.” Let us ponder this. First of all, the hotel is abandoned, supposedly (again, what option do you have but to trust my German?) to be renovated: The vacancy of the place, prevents me from any kind of contact with living human beings, but maybe the person who forced Chekhov to leave because his coughing was ANNOYING PEOPLE finds himself trapped in here, haunting the halls, tormented by remorse. Maybe something like widowed Olga in “The Grasshopper” (попрыгунья), who learned too late how famous her husband was.

The vacancy of the place, prevents me from any kind of contact with living human beings, but maybe the person who forced Chekhov to leave because his coughing was ANNOYING PEOPLE finds himself trapped in here, haunting the halls, tormented by remorse. Maybe something like widowed Olga in “The Grasshopper” (попрыгунья), who learned too late how famous her husband was.

there, that much is true. For an extremely short time. And they get credit for it.

there, that much is true. For an extremely short time. And they get credit for it. Just repeating here: “LIVED” (and then, for those concerned with precision, I actually checked this one on line, and yes, that’s what it says). Which is quite beautiful to ponder. And it was out this window that his soul flew, filling the square outside it and still living today. Which now bears his name, recognizable despite the weird German spelling:

Just repeating here: “LIVED” (and then, for those concerned with precision, I actually checked this one on line, and yes, that’s what it says). Which is quite beautiful to ponder. And it was out this window that his soul flew, filling the square outside it and still living today. Which now bears his name, recognizable despite the weird German spelling:

Soon there was a monument (more on this later, too), and then an actual Chekhov museum, the Chekhov Salon, and then a bronze seagull just outside his window.

Soon there was a monument (more on this later, too), and then an actual Chekhov museum, the Chekhov Salon, and then a bronze seagull just outside his window.

which I had the opportunity to learn tromping around town means “monument” and already knowing the story about it being melted down). To fill the empty place, someone made a crazy Chekhov bronze, complete with characters from his stories (look below for this one). And there’s an amazing story about ANOTHER Chekhov monument brought from SAKHALIN ISLAND here by one of the truly devoted Chekhov fans like those I have encountered on this journey, which I will tell about in the next blog post, for it is a story of heroism and martyrdom. For now, more about the museum. Somehow I thought this Tschechow Salon would be just an ordinary Literary museum with lots of writers in it, all balanced evenly, but actually this is a CHEKHOV place–with ancillary writers strewn around–Stephen Crane, some guy named Heidigger, others, too. But no doubt about it, this is his place, just one room–like him, modest, not showy, but full of content and quality. Some people planted cherry trees out front (from Taganrog, I think, so there’s a circle of birth to death, but also life being lived by the trees and by all the people walking through, and even stopping here, like me). Everything here is in German, so my brain is jumbled with it all, but the story is familiar–you can follow it in the photos displayed here, and of course because you know a lot of the story already, and supplement it by bumbling through the German inscriptions for cognates, of which there are disappointingly few. There is quite the political history here (German-Russian-Soviet-post-Soviet relations, with a conscious effort to focus on the cultural ties, which of course is also Chekhovian). It wasn’t so clear to me before in other places, but i can feel it now–that this place exists because of so many readers who appreciated Chekhov and honored him, and put in the effort to make this salon in his memory. And I am one of them too. Here is where the tears well up, because, OK, it’s Germany, he was away from home, like me, and ill, dying as everyone knew, though he carried on as though not, and all of this we behold here, the museum with its contents. And he did die here, which is why there is so much Chekhov in this town now. Otherwise, Badenweiler would have carried on its history and gone for Stephen Crane or someone more local instead. And I would never have visited. This town was for healing, though, which is what brought him here, and maybe me too. And his spirit, which flew out the window just catty-cornered to the museum, lives here.

which I had the opportunity to learn tromping around town means “monument” and already knowing the story about it being melted down). To fill the empty place, someone made a crazy Chekhov bronze, complete with characters from his stories (look below for this one). And there’s an amazing story about ANOTHER Chekhov monument brought from SAKHALIN ISLAND here by one of the truly devoted Chekhov fans like those I have encountered on this journey, which I will tell about in the next blog post, for it is a story of heroism and martyrdom. For now, more about the museum. Somehow I thought this Tschechow Salon would be just an ordinary Literary museum with lots of writers in it, all balanced evenly, but actually this is a CHEKHOV place–with ancillary writers strewn around–Stephen Crane, some guy named Heidigger, others, too. But no doubt about it, this is his place, just one room–like him, modest, not showy, but full of content and quality. Some people planted cherry trees out front (from Taganrog, I think, so there’s a circle of birth to death, but also life being lived by the trees and by all the people walking through, and even stopping here, like me). Everything here is in German, so my brain is jumbled with it all, but the story is familiar–you can follow it in the photos displayed here, and of course because you know a lot of the story already, and supplement it by bumbling through the German inscriptions for cognates, of which there are disappointingly few. There is quite the political history here (German-Russian-Soviet-post-Soviet relations, with a conscious effort to focus on the cultural ties, which of course is also Chekhovian). It wasn’t so clear to me before in other places, but i can feel it now–that this place exists because of so many readers who appreciated Chekhov and honored him, and put in the effort to make this salon in his memory. And I am one of them too. Here is where the tears well up, because, OK, it’s Germany, he was away from home, like me, and ill, dying as everyone knew, though he carried on as though not, and all of this we behold here, the museum with its contents. And he did die here, which is why there is so much Chekhov in this town now. Otherwise, Badenweiler would have carried on its history and gone for Stephen Crane or someone more local instead. And I would never have visited. This town was for healing, though, which is what brought him here, and maybe me too. And his spirit, which flew out the window just catty-cornered to the museum, lives here.

The internet is better here too. This afternoon I made an inquiry at the front desk, something quite banal about a towel, but in the process I realized I could ask about Chekhov’s room. So I flashed the blog, which brought on an administrator (the inquiry, not the blog). It turns out that she is Russian, and not only Russian, but a former MGU Philosophy professor, and we immediately tumble into Russian. After solving my banal towel problem we babble on about many Russian matters, from Chekhov to tragic world events, and she informs me that Chekhov left here because it was boring (as he wrote in a letter. If this blog were more scholarly I’d quote the letter here and maybe I will, later). In any case, this hotel was also renovated, but it has real people in it, mixed in with the ghosts. And here, as in all the Chekhov places, there are bits of him in the air–which is very very good for breathing, I have had some time to learn. There’s even an INHALATORIUM in town,

The internet is better here too. This afternoon I made an inquiry at the front desk, something quite banal about a towel, but in the process I realized I could ask about Chekhov’s room. So I flashed the blog, which brought on an administrator (the inquiry, not the blog). It turns out that she is Russian, and not only Russian, but a former MGU Philosophy professor, and we immediately tumble into Russian. After solving my banal towel problem we babble on about many Russian matters, from Chekhov to tragic world events, and she informs me that Chekhov left here because it was boring (as he wrote in a letter. If this blog were more scholarly I’d quote the letter here and maybe I will, later). In any case, this hotel was also renovated, but it has real people in it, mixed in with the ghosts. And here, as in all the Chekhov places, there are bits of him in the air–which is very very good for breathing, I have had some time to learn. There’s even an INHALATORIUM in town,

tudent at Moscow State University. And it was about a block away from Bolshoi Golovin St. (formerly Sobolev Street), the brothel district which served as the setting for his famous

tudent at Moscow State University. And it was about a block away from Bolshoi Golovin St. (formerly Sobolev Street), the brothel district which served as the setting for his famous story “An Attack of Nerves.” I tracked down several of these addresses, and looked around online, and it soon became clear that these paths were well trodden, and in fact there have been other, similar blog quests. When I popped into Dom Knigi one day and came upon a book that detailed every Chekhov address in Moscow, with a description of what he did while living there, I realized that my quest was evolving into something different. And the buildings all started to look alike anyway.

story “An Attack of Nerves.” I tracked down several of these addresses, and looked around online, and it soon became clear that these paths were well trodden, and in fact there have been other, similar blog quests. When I popped into Dom Knigi one day and came upon a book that detailed every Chekhov address in Moscow, with a description of what he did while living there, I realized that my quest was evolving into something different. And the buildings all started to look alike anyway. Russian literature scholars Sergei Kibalnik and Vladimir Kataev, who gave me some great leads. Soon it became clear th

Russian literature scholars Sergei Kibalnik and Vladimir Kataev, who gave me some great leads. Soon it became clear th at this would be a journey as much from person to person as from place to place. In every Siberian city I visited (except for Khabarovsk), I was hosted by generous colleagues–none of whom I had even met before–who showed me the very best their Chekhov or Dostoevsky place has to offer. And then helped me on my way. So the trip was not about places at all. It was about people.

at this would be a journey as much from person to person as from place to place. In every Siberian city I visited (except for Khabarovsk), I was hosted by generous colleagues–none of whom I had even met before–who showed me the very best their Chekhov or Dostoevsky place has to offer. And then helped me on my way. So the trip was not about places at all. It was about people.

is a kind of maximalistic impulse at work, a desire to go deep into the book and retrieve every nuance, meaning, and reference that connects the text with the world. And that world includes us readers.

is a kind of maximalistic impulse at work, a desire to go deep into the book and retrieve every nuance, meaning, and reference that connects the text with the world. And that world includes us readers.

Regrettably, I missed Shaman Gabyshev’s visit to Ulan-Ude by a few days, though we did breathe the same air. Despite the vast differences of time (over three centuries) and creed (he is most decidedly not an Old Believer), I was struck by some similarities between his mission and that of one of our blog heroes, Avvakum of Tobolsk. (I don’t think I mentioned this, but Avvakum was ultimately burned at the stake in 1682).

Regrettably, I missed Shaman Gabyshev’s visit to Ulan-Ude by a few days, though we did breathe the same air. Despite the vast differences of time (over three centuries) and creed (he is most decidedly not an Old Believer), I was struck by some similarities between his mission and that of one of our blog heroes, Avvakum of Tobolsk. (I don’t think I mentioned this, but Avvakum was ultimately burned at the stake in 1682). monolithic, absolute power, his clear-eyed sense of mission, the extraordinary might of the individual against a corrupt state – we saw it all with the archpriest. This is how change happens in Russia, and even when change doesn’t happen, this is how we get glimpses into the often invisible forces of spirit that lurk beneath the transient concerns of the moment. We will loop back to Ulan-Ude’s shamanism in a few minutes.

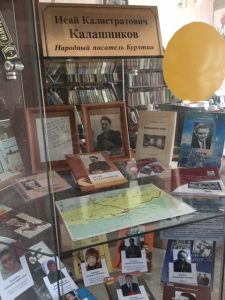

monolithic, absolute power, his clear-eyed sense of mission, the extraordinary might of the individual against a corrupt state – we saw it all with the archpriest. This is how change happens in Russia, and even when change doesn’t happen, this is how we get glimpses into the often invisible forces of spirit that lurk beneath the transient concerns of the moment. We will loop back to Ulan-Ude’s shamanism in a few minutes. Chekhov brought me to Ulan-Ude. He occupies a quiet corner in what Ulan-Ude calls its Arbat – a pleasant pedestrian district down the street from the more formal, official city center with its Lenin statue, government buildings, and theatrical square. After crossing Lake Baikal on June 14, 1890, Chekhov traveled southeast for about 100 kilometers, until he reached this city, which was then called Verkhne-Udinsk. Ulan-Ude is the capital of the Republic of Buryatia.

Chekhov brought me to Ulan-Ude. He occupies a quiet corner in what Ulan-Ude calls its Arbat – a pleasant pedestrian district down the street from the more formal, official city center with its Lenin statue, government buildings, and theatrical square. After crossing Lake Baikal on June 14, 1890, Chekhov traveled southeast for about 100 kilometers, until he reached this city, which was then called Verkhne-Udinsk. Ulan-Ude is the capital of the Republic of Buryatia.

bizarre Lenin head (yes, just the head) dominating its central square.

bizarre Lenin head (yes, just the head) dominating its central square.

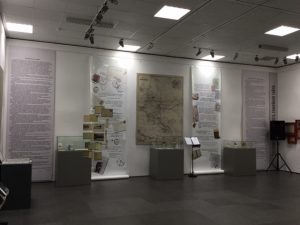

Speaking of tsars, just up the street, at the city’s historical and ethnographic museum, you can see original items belonging to another powerful individual, the blue submarine (or bathysphere) suit that Vladimir Putin wore when he came out here and dive-boated into Baikal in connection with a scientific exhibition. The cute nerpa banner conveys the message that this was a mission to save the environment. The museum is worth a visit even over and above this presidential sighting, as it gives a sense of the area’s diverse history;

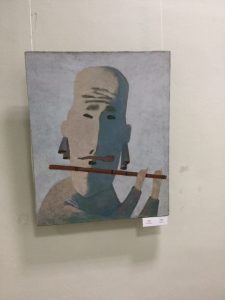

Speaking of tsars, just up the street, at the city’s historical and ethnographic museum, you can see original items belonging to another powerful individual, the blue submarine (or bathysphere) suit that Vladimir Putin wore when he came out here and dive-boated into Baikal in connection with a scientific exhibition. The cute nerpa banner conveys the message that this was a mission to save the environment. The museum is worth a visit even over and above this presidential sighting, as it gives a sense of the area’s diverse history;  Old Russian believers built settlements here as they were chased out of European Russia; Buryat communities maintained their way of life, herding animals, living in yurts, and practicing their unique religion with its shamanistic rituals. Buddhism in its Tibetan form coexisted with the native shamanistic religion. And of course there was Russian Orthodoxy, seasoned with official Soviet atheism in the 20th century. Among the works on exhibit by Bato Dashitsyrenov in the city’s art museum are extraordinary depictions of shamans in action.

Old Russian believers built settlements here as they were chased out of European Russia; Buryat communities maintained their way of life, herding animals, living in yurts, and practicing their unique religion with its shamanistic rituals. Buddhism in its Tibetan form coexisted with the native shamanistic religion. And of course there was Russian Orthodoxy, seasoned with official Soviet atheism in the 20th century. Among the works on exhibit by Bato Dashitsyrenov in the city’s art museum are extraordinary depictions of shamans in action.

explaining this monument; it might have something to do with the creation of the world, or a sort of scheme or hierarchy of life, but I will spare you that. It may be some comfort for you to know that I visited this exhibit with two different people, the museum’s director and an art scholar, and their explanations for most of the art on exhibit significantly differed among themselves. I loved this, and was convinced by both interpretations (in addition to my own secret ones, which I will spare you).

explaining this monument; it might have something to do with the creation of the world, or a sort of scheme or hierarchy of life, but I will spare you that. It may be some comfort for you to know that I visited this exhibit with two different people, the museum’s director and an art scholar, and their explanations for most of the art on exhibit significantly differed among themselves. I loved this, and was convinced by both interpretations (in addition to my own secret ones, which I will spare you).

I honestly don’t know who these two horsemen are, but they face the train station from behind, overlooking the most horrifying set of stairs I have ever seen–the innocently named “viaduct” that takes the weary traveler from the train station to her hotel, which google maps claims is an easy walk. You do not start at the top; rather, you had to climb four flights of steps to reach the top, from the train platform (carrying your luggage, which you will soon feel as an unnecessary burden, like all things of this world). The stairs seem to end right above that white car. But in fact, you cross that bridge to your left, and there

I honestly don’t know who these two horsemen are, but they face the train station from behind, overlooking the most horrifying set of stairs I have ever seen–the innocently named “viaduct” that takes the weary traveler from the train station to her hotel, which google maps claims is an easy walk. You do not start at the top; rather, you had to climb four flights of steps to reach the top, from the train platform (carrying your luggage, which you will soon feel as an unnecessary burden, like all things of this world). The stairs seem to end right above that white car. But in fact, you cross that bridge to your left, and there

at the wheel – and you may be lucky enough to see some more horses, these just wandering around, unfenced. This is my ultimate conception of freedom. My excitement was such that Alexander turned off the road and we kind of chased them for a while. (Special thanks to Sasha for doing this, and for being such a careful, expert driver who prefers the right, the correct, lane). These horses led us to lunch.

at the wheel – and you may be lucky enough to see some more horses, these just wandering around, unfenced. This is my ultimate conception of freedom. My excitement was such that Alexander turned off the road and we kind of chased them for a while. (Special thanks to Sasha for doing this, and for being such a careful, expert driver who prefers the right, the correct, lane). These horses led us to lunch.

Of the dishes on hand, I had only ever tried the buuza, but in its Mongolian variant, at that. There was a kind of Asian custard, like ice cream but not cold or sweet. My favorite was the sheep liver, but the entrail sausages tucked into sheep intestine were also a savory, once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Of the dishes on hand, I had only ever tried the buuza, but in its Mongolian variant, at that. There was a kind of Asian custard, like ice cream but not cold or sweet. My favorite was the sheep liver, but the entrail sausages tucked into sheep intestine were also a savory, once-in-a-lifetime experience.

The central temple enshrines the 12th Pandito Hambo Lama of the Ivolginsky Datsan, Dashi-Dorzho Itigelov, a revered spiritual leader whose body miraculously does not decay.

The central temple enshrines the 12th Pandito Hambo Lama of the Ivolginsky Datsan, Dashi-Dorzho Itigelov, a revered spiritual leader whose body miraculously does not decay.

The building stands, though it is no longer a hotel. At the time Chekhov could not have known that some 130 years later, just a bit down and across the street, a fine coffee shop, the White Crow (Belaya Vorona) would overjoy and refresh a weary Chekhov acolyte from far away.

The building stands, though it is no longer a hotel. At the time Chekhov could not have known that some 130 years later, just a bit down and across the street, a fine coffee shop, the White Crow (Belaya Vorona) would overjoy and refresh a weary Chekhov acolyte from far away.

It takes some effort, walking through these rooms, to recall the suffering hidden behind the walls of these islands of civilization: the families’ separation from their loved ones back home, and their knowledge that their cause of political reform had failed. Not to mention that their punishment included laboring in Siberian mines and other unpleasant activities…

It takes some effort, walking through these rooms, to recall the suffering hidden behind the walls of these islands of civilization: the families’ separation from their loved ones back home, and their knowledge that their cause of political reform had failed. Not to mention that their punishment included laboring in Siberian mines and other unpleasant activities…

One convenient feature of Irkutsk is its many Beeline shops. Here one can receive free psychotherapy in exchange for letting the specialists admire, I mean play with, I mean use, your passport to solve your cell- phone problems.

One convenient feature of Irkutsk is its many Beeline shops. Here one can receive free psychotherapy in exchange for letting the specialists admire, I mean play with, I mean use, your passport to solve your cell- phone problems.

This particular Chekhov offers quite a contrast to his barefooted Tomsk version. Which is OK; there are many Chekhovs, and many ways of viewing (and reading) him. Let Krasnoyarsk have this Chekhov. And since Chekhov is my role model, let me, too, stand up straighter, flip my scarf to one side and make a half-turn into the wind.

This particular Chekhov offers quite a contrast to his barefooted Tomsk version. Which is OK; there are many Chekhovs, and many ways of viewing (and reading) him. Let Krasnoyarsk have this Chekhov. And since Chekhov is my role model, let me, too, stand up straighter, flip my scarf to one side and make a half-turn into the wind.