It’s exciting when a quiet place you’ve just visited becomes a world news headline. The other day, the New York Times reported on a shaman’s visit to Ulan-Ude. The shaman, Aleksandr Gabyshev, was walking westward across Russia; his ultimate goal – to reach Moscow and exorcise Putin’s demons. He says: “In him there is much evil, and he himself embodies the powers of evil, so an exorcism must be done.” The shaman has been arrested by the “dark forces” of the State, and now finds himself exiled in Yakutsk facing threat of forced treatment in a psychiatric institution (a time-honored tactic that lingers from the Soviet period). But his visit sparked anti-government protests in Ulan-Ude. Read the story here, then we will proceed:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/09/world/europe/shaman-putin-dissent.html

Regrettably, I missed Shaman Gabyshev’s visit to Ulan-Ude by a few days, though we did breathe the same air. Despite the vast differences of time (over three centuries) and creed (he is most decidedly not an Old Believer), I was struck by some similarities between his mission and that of one of our blog heroes, Avvakum of Tobolsk. (I don’t think I mentioned this, but Avvakum was ultimately burned at the stake in 1682).

Regrettably, I missed Shaman Gabyshev’s visit to Ulan-Ude by a few days, though we did breathe the same air. Despite the vast differences of time (over three centuries) and creed (he is most decidedly not an Old Believer), I was struck by some similarities between his mission and that of one of our blog heroes, Avvakum of Tobolsk. (I don’t think I mentioned this, but Avvakum was ultimately burned at the stake in 1682).

Higher forces are at work, demons are threatening Russia; a lone man stands up in the depths of Siberia, looks evil in the eye, and speaks his truth. Others heed the call and before you know it, crowds gather in the streets. Thе man is prophet, poet, holy fool; he is shaman. Mr. Gabyshev’s suicidal challenge to  monolithic, absolute power, his clear-eyed sense of mission, the extraordinary might of the individual against a corrupt state – we saw it all with the archpriest. This is how change happens in Russia, and even when change doesn’t happen, this is how we get glimpses into the often invisible forces of spirit that lurk beneath the transient concerns of the moment. We will loop back to Ulan-Ude’s shamanism in a few minutes.

monolithic, absolute power, his clear-eyed sense of mission, the extraordinary might of the individual against a corrupt state – we saw it all with the archpriest. This is how change happens in Russia, and even when change doesn’t happen, this is how we get glimpses into the often invisible forces of spirit that lurk beneath the transient concerns of the moment. We will loop back to Ulan-Ude’s shamanism in a few minutes.

Chekhov brought me to Ulan-Ude. He occupies a quiet corner in what Ulan-Ude calls its Arbat – a pleasant pedestrian district down the street from the more formal, official city center with its Lenin statue, government buildings, and theatrical square. After crossing Lake Baikal on June 14, 1890, Chekhov traveled southeast for about 100 kilometers, until he reached this city, which was then called Verkhne-Udinsk. Ulan-Ude is the capital of the Republic of Buryatia.

Chekhov brought me to Ulan-Ude. He occupies a quiet corner in what Ulan-Ude calls its Arbat – a pleasant pedestrian district down the street from the more formal, official city center with its Lenin statue, government buildings, and theatrical square. After crossing Lake Baikal on June 14, 1890, Chekhov traveled southeast for about 100 kilometers, until he reached this city, which was then called Verkhne-Udinsk. Ulan-Ude is the capital of the Republic of Buryatia.A companion on a walk through town, an anonymous philologist from Buryat State University, shows me the hotel where Chekhov stayed.

and kindly helps orient me in Buryat cuisine.

Ulan-Ude’s physical center teems with reminders of its Soviet history: its imposing Memorial to the Great Fatherland War, streets named after the same Soviet leaders we saw in our other Siberian towns, a town square featuring and a truly  bizarre Lenin head (yes, just the head) dominating its central square.

bizarre Lenin head (yes, just the head) dominating its central square.

The thing is huge, and for some reason in the evening was illuminated with an eerie green light. In Ulan-Ude I found myself in a new world that yet is completely familiar. Here we recognize the layers of history – the trappings of 21st-century political and economic system resting uneasily in the Soviet architecture, monuments testifying to the ravages of war, the brute power of dictators, the clashes between empire and periphery, and, moving backward to a time whose buildings are lost, the quiet spirits of the place who continue to fill the air with their truth.

Speaking of tsars, just up the street, at the city’s historical and ethnographic museum, you can see original items belonging to another powerful individual, the blue submarine (or bathysphere) suit that Vladimir Putin wore when he came out here and dive-boated into Baikal in connection with a scientific exhibition. The cute nerpa banner conveys the message that this was a mission to save the environment. The museum is worth a visit even over and above this presidential sighting, as it gives a sense of the area’s diverse history;

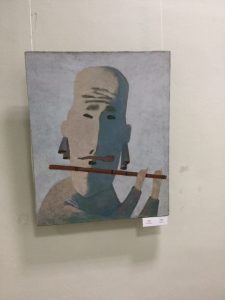

Speaking of tsars, just up the street, at the city’s historical and ethnographic museum, you can see original items belonging to another powerful individual, the blue submarine (or bathysphere) suit that Vladimir Putin wore when he came out here and dive-boated into Baikal in connection with a scientific exhibition. The cute nerpa banner conveys the message that this was a mission to save the environment. The museum is worth a visit even over and above this presidential sighting, as it gives a sense of the area’s diverse history;  Old Russian believers built settlements here as they were chased out of European Russia; Buryat communities maintained their way of life, herding animals, living in yurts, and practicing their unique religion with its shamanistic rituals. Buddhism in its Tibetan form coexisted with the native shamanistic religion. And of course there was Russian Orthodoxy, seasoned with official Soviet atheism in the 20th century. Among the works on exhibit by Bato Dashitsyrenov in the city’s art museum are extraordinary depictions of shamans in action.

Old Russian believers built settlements here as they were chased out of European Russia; Buryat communities maintained their way of life, herding animals, living in yurts, and practicing their unique religion with its shamanistic rituals. Buddhism in its Tibetan form coexisted with the native shamanistic religion. And of course there was Russian Orthodoxy, seasoned with official Soviet atheism in the 20th century. Among the works on exhibit by Bato Dashitsyrenov in the city’s art museum are extraordinary depictions of shamans in action.

The artist also proposed a monument that in my opinion would be a fitting addition, or replacement to the public square, possibly near a Tomsk Chekhov clone. I would take a stab at  explaining this monument; it might have something to do with the creation of the world, or a sort of scheme or hierarchy of life, but I will spare you that. It may be some comfort for you to know that I visited this exhibit with two different people, the museum’s director and an art scholar, and their explanations for most of the art on exhibit significantly differed among themselves. I loved this, and was convinced by both interpretations (in addition to my own secret ones, which I will spare you).

explaining this monument; it might have something to do with the creation of the world, or a sort of scheme or hierarchy of life, but I will spare you that. It may be some comfort for you to know that I visited this exhibit with two different people, the museum’s director and an art scholar, and their explanations for most of the art on exhibit significantly differed among themselves. I loved this, and was convinced by both interpretations (in addition to my own secret ones, which I will spare you).

I can’t help it, I just love this artist. Check out “See no Evil” and a couple of other masterpieces, basically, I’d say, about the human condition:

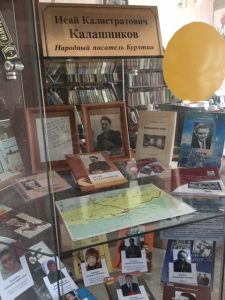

My host throughout my visit to Ulan-Ude is Professor Svetlana Imikhelova of Buryat State University. Svetlana orients me geographically, and takes me to the city library, where I learn about the area’s vibrant literary tradition and support for the arts. I am most curious to learn about a famous novel by Isai Kalashnikov, about the life of a Mongolian boy called Temujin, who grew up to be Genghis Khan.

Svetlana then entrusts me to the care of the director of Ulan-Ude’s art museum, where, indeed, I encountered, in addition to Dashitsyrenov’s amazing art, many other wonderful works as well, by nineteenth-century works by such famous Russian artists as Repin, Levitan,

Chekhov alert!

Repin, and Kuindji.

Now I just want to say that Ulan-Ude and its environs are an excellent locale for horse-spotting. You will certainly recall Dashitsyrenov’s frolicing horse from Tomsk, I mean, from Ulan-Ude.

I am told that Japanese prisoners of war worked on the equestrian topping for the city’s Theater of Opera and Ballet, which recalls the one above Moscow’s Bolshoi Theater, though here there are fewer horses.

You (or rather, your inner fantasy child) can take a ride on this pony who stands near the Great Fatherland War monument.

I honestly don’t know who these two horsemen are, but they face the train station from behind, overlooking the most horrifying set of stairs I have ever seen–the innocently named “viaduct” that takes the weary traveler from the train station to her hotel, which google maps claims is an easy walk. You do not start at the top; rather, you had to climb four flights of steps to reach the top, from the train platform (carrying your luggage, which you will soon feel as an unnecessary burden, like all things of this world). The stairs seem to end right above that white car. But in fact, you cross that bridge to your left, and there

I honestly don’t know who these two horsemen are, but they face the train station from behind, overlooking the most horrifying set of stairs I have ever seen–the innocently named “viaduct” that takes the weary traveler from the train station to her hotel, which google maps claims is an easy walk. You do not start at the top; rather, you had to climb four flights of steps to reach the top, from the train platform (carrying your luggage, which you will soon feel as an unnecessary burden, like all things of this world). The stairs seem to end right above that white car. But in fact, you cross that bridge to your left, and there

there are another twenty (or so, it seems) flights down to street level. Then you walk up a long slow hill, cursing your cell phone with what is left of your voice, until eventually you reach the hotel. Somehow I feel that the equestrian statues there were a kind of warning about this, but cryptic.

Focus.

Travel outside of town with Svetlana –with her son Alexander at the wheel – and you may be lucky enough to see some more horses, these just wandering around, unfenced. This is my ultimate conception of freedom. My excitement was such that Alexander turned off the road and we kind of chased them for a while. (Special thanks to Sasha for doing this, and for being such a careful, expert driver who prefers the right, the correct, lane). These horses led us to lunch.

at the wheel – and you may be lucky enough to see some more horses, these just wandering around, unfenced. This is my ultimate conception of freedom. My excitement was such that Alexander turned off the road and we kind of chased them for a while. (Special thanks to Sasha for doing this, and for being such a careful, expert driver who prefers the right, the correct, lane). These horses led us to lunch.

Of the dishes on hand, I had only ever tried the buuza, but in its Mongolian variant, at that. There was a kind of Asian custard, like ice cream but not cold or sweet. My favorite was the sheep liver, but the entrail sausages tucked into sheep intestine were also a savory, once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Of the dishes on hand, I had only ever tried the buuza, but in its Mongolian variant, at that. There was a kind of Asian custard, like ice cream but not cold or sweet. My favorite was the sheep liver, but the entrail sausages tucked into sheep intestine were also a savory, once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Horses and lunch were a mere coda to the centerpiece of my entire visit to Ulan-Ude: a trip to the famous Ivolginsk Datsan outside of town. If you are not lucky enough to have Sasha drive you, you can come on Bus # 108. If you know something about Tibetan Buddhism, this number will have special meaning for you.

You walk clockwise around the periphery of the datsan complex, circling the prayer drums and twirling them as you go.  The central temple enshrines the 12th Pandito Hambo Lama of the Ivolginsky Datsan, Dashi-Dorzho Itigelov, a revered spiritual leader whose body miraculously does not decay.

The central temple enshrines the 12th Pandito Hambo Lama of the Ivolginsky Datsan, Dashi-Dorzho Itigelov, a revered spiritual leader whose body miraculously does not decay.

Learn details of the story here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d9ETr7_GtHw&fbclid=IwAR219J3a-R9WIbWkpjEN0dIu1txARjWitYIwnojKw_kiGFIsAylQrnfgT50

His spirit fills the air here, and even as you make your wish and prayer for the future, you know that it is already fulfilled here and now.

I have also left some of my spirit here, and in Ulan-Ude, and everywhere else I have visited on this journey.

Leave a Reply