Georgette Heyer and Barbara Cartland

by Nicola Morris (2020)

Introduction

Georgette Heyer, an author of historical Regency romances stated she “would rather by far that a common thief broke in and stole all the silver” than have to read a novel from Barbara Cartland’s A Saga of Hearts trilogy, which Heyer claimed Cartland had plagiarized from her own novels (Heyer, 8). In May of 1950, after being informed of the potential plagiarism by a fan, Heyer wrote a series of letters to her literary agent, L.P Moore, detailing the accusation and her feeling towards it.

Based on Georgette Heyer’s letters to her literary agent, I argue in this paper that Heyer’s biggest grievance of Barbara Cartland’s plagiarism was her unauthorized borrowing of Regency-era phrases and names without a deep understanding or extensive research into the period. Additionally, a comparison of the novels support’s Heyer’s claim of plagiarisms in Cartland’s Knave of Hearts.

Georgette Heyer

Georgette Heyer began writing novels at the age of seventeen, publishing her first novel only two years later at the age of nineteen (“Georgette Heyer, Historical Novelist”). During her fifty-year career, beginning in 1921 and ending in 1974, Heyer wrote over fifty novels, the majority of which were historical romances, set in Regency England in the early 1800’s (“Georgette Heyer”). Heyer led a very private life, “shunning all publicity, maintaining that readers would find all they needed to know about her in her books” (“Georgette Heyer”). Heyer’s novels were often cheerful, but unorthodox historical novels. Heyer “soak[ed] herself in the Regency period [and] became an expert on the history and manners of that time” (Arnold). Reviews of her novels often highlighted the authenticity in which she portrayed Regency England. A fan of Heyer wrote, “There is so much detailed descriptions of food, clothes, furnishings, transport…creating a picture of [the Regency period] (Arnold).

Barbara Cartland

Barbara Cartland received significantly more fame and acclaim during her seventy-five-year career. She published her first novel in 1925, and her novels continued to be published until 2011, even eleven years after her death. She wrote over 700 novels, all of which were “sweet” and most of which were historical romances (Bader). She received the Guinness World Record for publishing the most books in a single year (Bader). It is estimated that she sold over one billion copies of her novels throughout her career. She was often mentioned in The New York Times, Vogue and other popular magazines with high praise. Unlike Heyer, Cartland never shied away from fame or publicity, and was referred to as the “the flamboyant queen of the romantic novel” (Borders). Cartland prided herself on writing traditional (non-sexual) romance novels, in which virginity was often closely linked with morality. In a 1973 interview with The New York Times she explained, “my heroines are always virgins; they never go to bed without a ring on their fingers—not until page 118 at least” (“At 71”).

Heyer’s Letters Regarding Cartland’s Plagiarism

Georgette Heyer did not often speak of her own work. Her publishers frequently referred to her as shy and reserved (Kloester, 281). However, in May of 1950, a fan wrote to her regarding possible plagiarism, informing Heyer that there was an author, Barbara Cartland who was “immersing herself in some of your books and making good use of them” (Kloester, 281). This ignited Heyer to energetically defend her own work. Heyer wrote a series of letters to her literary agent, Lenard Parker Moore (referred to as L.P.) regarding the plagiarism, expressing her anger and providing evidence of her accusation. The letters, which were written from May 21 – 24, 1950, show Heyer’s wrath toward Cartland, and cite the theft of specific Regency names and phrases from her own novels.

Heyer focused her attention on three of Cartland’s novels A Hazard of Hearts, A Duel of Hearts, Knave of Hearts, part of A Saga of Hearts trilogy. Before writing her letter on May 21, 1950, she spent a “revolting” week reading and comparing the “quite- awful” trilogy (Heyer, 1). In the first two novels, Heyer found that there were many instances of names and phrases that were taken from her own novels. And from Knave of Heart, Cartland’s third novel in the trilogy, Heyer “had not read more than a page when [she] reached for pencil, paper, and three of [her] own novels” (Heyer, 2). Given her knowledge and expertise of the period, she identifies that the phrases are often used incorrectly, and that Cartland uses no other period phrases than the ones found in Heyer’s novels (Heyer, 1). Heyer found one specific expression from a privately printed book, lent to her by a descendant of a lieutenant. The expression had not been used elsewhere; therefore, Heyer did not believe Cartland would have had known this expression without plagiarizing it from Heyer’s novel (Heyer, 1).

Throughout the letters, Heyer expressed the different ways in which she wanted to approach the plagiarism. She writes to L.P. on May 21 that she had been advised by her husband to make a case and submit it to a copyright barrister (Heyer, 2). Within this same letter, she expressed her doubt of it ever going to court, bur confident that if it did, it would be clear that Cartland would be found guilty of plagiarism (Heyer, 2). On May 24, Heyer indicated her interest in collecting damages; with her reasons including Cartland’s wealthy husband as well as the fact that Heyer “wasted much time, caused much annoyance, and spent money on buying copies of her works” (Heyer, 8) Included with this letter to L.P. was a letter in which Heyer proposed to send to her lawyer for the “Counsel’s perusal” (Heyer, 8)

Heyer’s Greatest Grievance

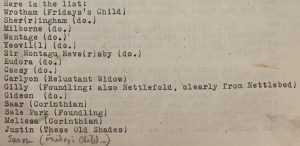

Heyer was enraged by Cartland’s plagiarism of Regency names and phrases without a full understanding of the time period. Heyer was an expert on the Regency period and did extensive research to depict an accurate portrayal of the time. In the May 24th letter to L.P., Heyer referenced her Regency notebook “which contains all of [her] phraseology, most of which the sources attached” (Heyer, 8). Unlike Heyer, who prided herself on her extensive research process, “Miss Cartland knows nothing whatsoever about the period. She has lifted certain things from me, that’s all” (Heyer, 2). Although Cartland’s trilogy was set in the Regency period, the dialogue and social practices of the novels are a mix of eighteen, nineteenth, and twentieth-century norms (Kloester, 194). Additionally, Heyer completed an in-depth analysis of Cartland’s novels in which she found over forty period phrases that were present in Heyer’s novels with citations (Kloester, 195). Heyer understood that these expression would be common among novels of the Regency genre, however, not only did Cartland often misuse regency phrases, but she did not use any period vocabulary that did not appear in Heyer’s novels (Kloester, 194). Throughout her letters to L.P., she expressed the most anger towards the lifting of Regency names and phrases as compared to the lifting of plot points. In her first letter to L.P., she provides a list of 16 “out-of-way” Christian names of which Cartland took from her novels (See Appendix). Heyer ends her letter from May 22 by writing, “I see no reason why I should permit her to cash in on either my ideas or research” (Heyer, 6).

Comparison of the Novels

While Heyer was angry about the plagiarism in all three of Cartland novels in A Saga of Hearts, her main concern centered on the third book, Knave of Heart, which contained the most frequent and egregious instances of plagiarism. The first two novels in Cartland’s trilogy bear little in common in terms of plot with Heyer’s novels. However, The Knave of Heart shared a series of common plot points and as well as a significant number of common names and phrases with Heyer’s Old Shades.

These Old Shades tells the story of Justin, the Duke of Avon, who is handsome, strong and mysterious. Justin comes in contact with an abused boy, Léon, who was running away from his brother and abuser. Justin takes pity on the boy and purchases him as his page (servant). Léon expresses his love and gratitude toward the Duke for taking him. Justin attends a party hosted by the Comte of Saint-Vire and soon realizes that Léon bears a strong resemblance to the Comte. Justin soon learns that Léon is actually a young lady, Léonie. It is later confirmed that Léonie is the true daughter of the Comte, and Léonie and the acting son of the Comte had been switched at birth for the Comte to prevent his younger brother from becoming his heir. The Duke takes Léonie to England and teaches her to become a lady and how to act in Parisian high society. The Comte, afraid that the truth may come out, kidnaps Léonie and brings her back to France. The Duke’s younger brother, Rupert helps Léonie escape and begins to express his feeling toward her. He attempts to convince her to leave the Duke by telling her that Justin is “Satan himself” (Heyer, 163). Léonie, overwhelmed with wrath, attacks him with a sword. After the Duke returns to France, Léonie hears rumors that she was born as the illegitimate child of the Comte and believes this status is ruining the Duke’s reputation. She runs away to the village in which she grew up. The Duke then realizes his feeling for Léonie, finds her, and proposes.

The hero of Cartland’s Knave of Heart is Sebastian, the Duke of Melcombe, who is a handsome, reckless, scandalous, and cynical. Early on, Sebastian is informed of his new status as the guardian of Ravella Shane, the daughter of his sister’s dear, but recently deceased, friends. After the death of both her parents, Ravella (and not her rebellious brother) becomes the heiress to her father’s fortune. Ravella is young, unconventional and rejects the ideas of becoming an heiress. Throughout the novel, Sebastian teaches Ravella how to behave like a true heiress. Ravella feels extreme gratitude and love toward the Duke. While living on Sebastian’s estate, Ravella develops a friendship with a young gardener named Adrian. Adrian soon develops feelings for Ravella and tries to convince her to leave the Duke’s estate. He calls the Duke “bad, wicked, and a man no decent woman would trust” (Cartland, 69) Overcome with anger, Ravella slashes Adrian with her riding-whip. Ravella continues to live on the Duke’s estate until she is told she is not the true heiress to the Shane fortune. Feeling unworthy, she runs away from the estate and is ultimately kidnapped and held as a prisoner. When the Duke learns of her disappearance he finds her, confesses his feeling and eventually proposes.

Common Elements

The short summaries of the novels show commonalities in major plot points. In both novels, a Duke is met with the opportunity to take care of a young girl. Both Ravella and Léonie are headstrong and need to be taught how to act in accordance with their upper-class status. Both girls feel love and gratitude toward their respective Dukes for taking them in. Both Ravella and Léonie fight men who try to undermine their Dukes. After learning about a change in their status as an heiress, both women shamefully run away. Both novels feature the Dukes discovering their feelings and running after, and proposing to the young women.

In the scenes of proposals, the similarities of the novels extend beyond the plot to the actual phrasing. In Knave of Heart, Ravella says in regard to Sebastian’s proposal, “I have never… in my most secret dreams…imagined that you might marry me, but I have thought perhaps … until you wearied me… I might come to you and be … your woman” (Cartland, 254). Cartland continues to describe how “Ravella’s faltering little voice died into silence for the first time since she has started speaking she raised her eyes to the Duke’s face and to her astonishment his eyes were blazing” (Cartland, 254). The Duke then said, “How dare you speak to me like that…how dare you compare yourself with those women” (Cartland, 254).

In These Old Shades, Léonie responds to Justin’s proposal by saying, “Monseigneur, I have never thought you would marry me … But if you wanted me, I thought perhaps you take me until I wearied you (Heyer, 350). There was then “a moment’s silence, then his Grace spoke so harshly that Léonie was startled.” Then Justin exclaims, “you are not to talk in that fashion, Léonie. You understand me” (Heyer, 350).

Conclusion

There is no record that solicitor’s letter that Heyer mentioned in her third to L.P. was ever sent or responded to. However, Heyer later wrote, “the horrible copies of my books [referring to Cartland’s novels] ceased abruptly” (Kloester, 285) Heyer’s interest in maintaining a private life allowed such a case of plagiarism to go unpublicized, despite the clarity of the plagiarism in both plot and writing. A review of Georgette Heyer’s letters to her literary agents indicated Heyer’s greatest issue with Cartland’s plagiarism. The lifting of Regency phrases and names was most egregious to Heyer who was a dedicated researcher of the time period.

Additionally, in 1976, The Knave of Heart was republished with a new title, The Innocent Heiress, and a nod to Heyer with the addition of “In the Tradition of Georgette Heyer” to the cover. There are two speculations as to why this acknowledgement was added to Cartland’s novel. The first would be to recognized the fundamental role that Heyer played in creating and developing the Regency genre, ands therefore absolving Cartland or any other author of the genre from accusations of plagiarism. The second explanation is a confession. While Cartland never spoke of the plagiarism, this change to her novel may have been a subtle admission of her own guilt. The title change, along with the acknowledgment of Heyer’s “Tradition” and the comparison of the novels provide significant evidence to support Heyer’s claim of plagiarism.

Appendix

Bibliography

Arnold, Peter, Rosalind Belben, Margaret B. Lodge, and Anne E. Limebear. “Miss Georgette Heyer’s Regency novels.” Times, October 3, 1970, 13. The Times Digital Archive.

Special to the New York Times. “At 71, Barbra Cartland is Still a Crusader” The New York Times, June 10, 1973.

Borders, William. “Barbara Cartland’s Touch of Royalty.” The New York Times, April 12, 1981.

Bader, Jenny Lyn. “WORD FOR WORD/ROMANCE NOVEL TITLES; How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Words.” The New York Times , May 28, 2000.

Cartland, Barbara. The Innocent Heiress. New York: Jove Publications, 1979.

“Georgette Heyer, Historical Novelist.” The Sun (1837-1994), Jul 06, 1974.

“Georgette Heyer Is Dead at 71; Wrote Regency England Novels.” The New York Times , July 6, 1974.

Heyer, Georgette. Papers, 1950-1952. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Heyer, Georgette. These Old Shades. London: William Heinemann, 1926.

Kloester, Jennifer. Georgette Heyer: Biography of a Bestseller. William Heinemann, 2011.

Kloester, Jennifer. “Georgette Heyer: writing the Regency: history in fiction from Regency Buck to Lady of Quality 1935-1972.” PhD thesis. The University of Melbourne, 2004.