Harlequin Enterprises in Japan and its Venture into the Manga Market

By Lexi Kadis (2018)

Introduction

Did you know that Harlequin romance is big in Japan? Not only are Harlequin’s Japanese translations popular, but so are the manga adaptations of its novels. Since setting up shop in Japan in 1979, Harlequin Enterprises has seen relative success in the romance novel market, so the company decided to enter the manga market in Japan in 1998. In the mid-2000s, the Japanese comic adaptations of Harlequin novels were made available in America in the English language. This report chronicles the history of Harlequin in Japan and its venture into the romance manga market. In addition, the report follows the cross-cultural translation and adaptation process that the Harlequin novels and comics underwent in both Japan and the United States.

History of Harlequin Enterprises in Japan

Harlequin Enterprises began to express interest in the Japanese market in the late 1970s (Grescoe 115). After Harlequin’s joint venture proposal for translated romance novels was rejected by Japanese publishers, the company decided to enter the market on its own (Grescoe 115). In 1984, Rei Tanaka, the managing director for the company’s Japanese operations in the early 1980s, noted that “a great deal of time and money was spent in conducting market research in Japan prior to the decision to launch” (41). Following two years of market research, which included a sample of 1,000 women who read Harlequins in Japanese, the company was convinced that foreign romances would thrive in the Japanese marketplace (Grescoe 115). Consequently, the subsidiary Harlequin Japan, also called Harlequin K.K., was launched in 1979 (Mulhern 51). In its annual report from 1980, the company indicated that the Japanese market was “expected to rival the USA in size” (quoted in Jensen 33). Harlequin Enterprises had high hopes for its Japanese office.

However, Harlequin romance novels were not an overnight success in Japan. As Tanaka noted, “market penetration does not happen overnight, especially when the product is not in sync with cultural values” (41). Eva Wirten, a scholar in communications studies, describes Harlequin’s cross-cultural translating process as “transediting” because translators must edit the novels to adhere to cultural norms (233). The company was forced to make changes to its novels in terms of English wording and cover art in order to appeal to Japanese readers (Grescoe 117). For example, translators had to remove English colloquialisms like “I’m over the moon with you!” that had no Japanese equivalent, and illustrators had to change cover art that showed a man and woman kissing because such images were not socially acceptable (Grescoe 117). Wirten explains how Harlequin’s international offices functioned independently from the headquarters in Canada: “they decide what books to publish, then they edit, translate, and print—all to ensure maximum adaptability to the particulars of their respective markets” (233). After making concessions to specific cultural tastes, Harlequin novels began to gain some traction in Japan.

Almost five years after its launch, Harlequin Japan had become a relatively successful publisher of Japanese translations. By 1984, the company was considered to be “well established” in the Japanese romance fiction market (Tanaka 41). According to the New York Times, the company achieved such success by “working with a Japanese distributor and then dealing directly with wholesalers and bookstores” (Chira 3001). By the late 1980s, Harlequin Japan was publishing a prolific number of translated novels. In 1987, they released thirteen romance series that contained 405 titles, which made up 40 percent of all British and American fiction that was published in Japanese that year (Mulhern 51). In 1986, the Chicago Tribune described the “raging industry” that had consumed Japan: “It has nothing to do with microchips or compact cars. It has to do with the literature of love. Yes, folks, the Japanese have contracted ‘Harlequin romance fever’” (Spencer). By the end of the decade, Harlequin had proven that its brand of romance and translation was a hit in Japan.

Despite the apparent popularity of its translated romance novels, sales in Japan failed to meet the company’s initial expectations. In 1996, the Canadian Business magazine noted that though Harlequin had made “substantial inroads into the Japanese market,” the sales of its Japanese-language novels lagged behind the sales of its translations in other countries: “The [Japanese] numbers are disappointing by Harlequin’s exacting standards” (McGugan 107). Back in 1984, Tanaka had predicted that the readings habits of the Japanese would pose a problem for the company: “Traditionally, reading books has been viewed as more of an academic pursuit…the young Japanese woman exhibits very different reading tastes…Magazines and manga are very popular” (42). Almost fifteen years after Tanaka made this observation, the company decided to try its hand in the manga publishing business.

Entering the Manga Market: Japan and the United States

Harlequin Japan wanted to tap into the highly successful manga market. Japanese comics, known as manga, are one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Japan (Ito, “History of Manga” 473). The comics are drawn by hand using pencils, erasers, pens, and brushes (Ito, “Japanese Ladies’” 68). Genres of manga are categorized according to the age and gender of the intended readership (Ito, “Japanese Ladies’” 69). Kinko Ito, who is a leading expert on Japanese popular culture and comics, describes the manga industry as a “huge and lucrative business” in Japan (“History of Manga” 456). Manga sales comprise 25 percent of the publications in Japan (Ito, “Japanese Ladies’” 68). In 2010, Stephen Miles, executive vice-president for Harlequin Japan, remarked that, “If you go into a bookstore in Japan…half the store is comics,” so the move into manga was a logical business venture (Cameron 24). Thus, as the company faced a growing lack of interest in traditional novels, it turned to the comic format (Bodsworth).

In particular, Harlequin chose to enter a niche market of manga called Japanese ladies’ comics. This genre emerged in the 1980s for a target audience of women in their twenties and thirties (Ogi 780). After 1985, the number of ladies’ comics magazines began to increase, and there were forty-eight magazines being published by 1991 (Ogi 780). These magazines were released bi-weekly, monthly, or bi-monthly (Ito, “Japanese Ladies’” 70). According to Ito, the early years of ladies’ comics were characterized by “freedom of sexual expression” (“History of Manga” 472). Ito argues that ladies’ comics were popular because the heroines had an agency that Japanese women lacked in their daily lives:

Japan is indeed is still a man’s paradise where men dominate the society, except in the domestic sphere, and in many areas of Japanese everyday life, women are often bystanders and cheerleaders rather than major players. In Redi Komi [Ladies’ Comics] stories, however, women are the heroines…The Redi Komi heroines are the major and active players who think, act, and live lives. Even though many heroines somehow make mistakes, they do learn from them, come up with solutions, and grow as human beings. Here is the fantastic world of the Japanese ladies’ comics where anyone can enjoy the vicarious experience as a heroine at any time and anywhere. (“Japanese Ladies’” 84)

Ladies’ comics appealed to women in Japan for one of the same reasons that romance novels appealed to women in America: the recurring theme of female empowerment (Krentz 5). Consequently, when Harlequin began to explore possible manga adaptations of its novels in the late 1990s, the genre of ladies’ comics was a match with the American romance novel in terms of thematic content and target audience.

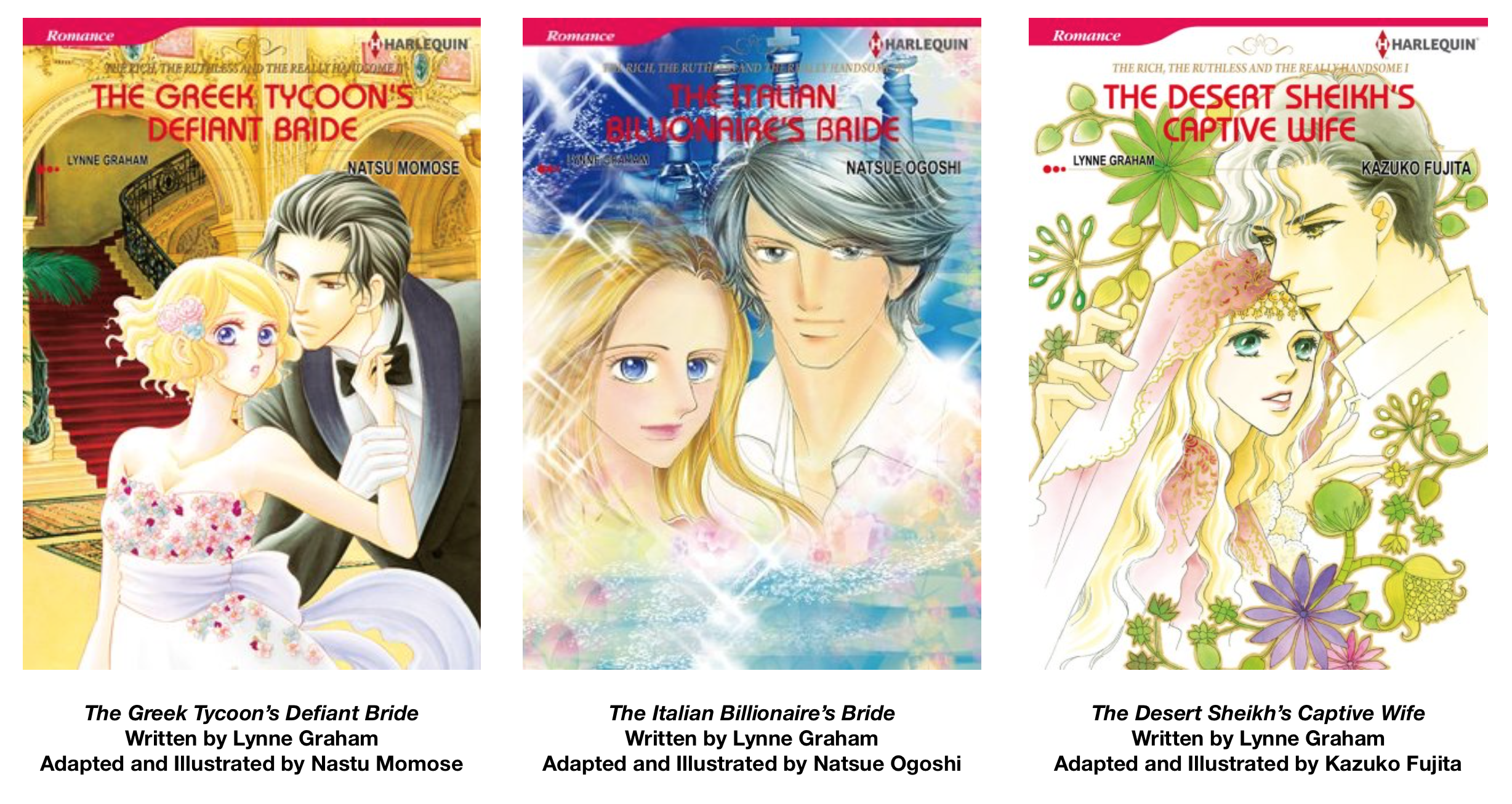

The company officially launched manga adaptations of its novels in 1998. Harlequin’s first comic was released by Ozora Publishing House, a Japanese manga publisher, in July 1998 (Ito, “Japanese Ladies’” 44). As part of its partnership with Harlequin, Ozora Publishing was responsible for contracting local artists to illustrate the translated Harlequin novels (Cameron 24). The adaptation of a Harlequin novel is a multi-step process. First, manga artists choose the stories that they will illustrate from a pool of Harlequin novels that have already been translated into Japanese; then, they create rough character sketches and a working summary for the comic (Harlequin’s Overseas Team). Designing the complete comic can take anywhere from three weeks to four months (Harlequin’s Overseas Team). Harlequin may choose to adapt an author’s series, but employ different artists for each book (see figure below). Kazuko Fujita, the illustrator for Lynne Graham’s The Desert Sheikh’s Captive Wife, compared her drawings with the other artists to ensure some amount of visual uniformity: “I exchanged my illustrations of the characters with the artists who made the other two books in the miniseries so that we could try to draw the characters in a similar way” (Harlequin’s Overseas Team). By employing a variety of artists, Harlequin comics are able to better suit the aesthetic tastes of different readers.

Image citations are listed in the bibliography under the illustrator’s name.

It is important to note that Harlequin authors have no input over the adaptation process. Lynne Graham, author of The Desert Sheikh’s Captive Wife (2008), indicated that she had “no role whatsoever in the adaptation,” but added that she was “very fond of the Japanese comic” which she found to be “full of drama and very emotive” (Graham E-mail). Similarly, Carole Devine, whose novel The Billionaire’s Secret Baby (1995) was adapted by Masako Ogimaru, wrote that, “Although [she] had no input in the Japanese illustrated version of The Billionaire’s Secret Baby, [she] was very pleased with the result” (Devine E-mail). While some authors expressed satisfaction with the comic adaptations despite their lack of input, others were unhappy with the final product. For example, Sandra Marton, author of Blackwolf’s Redemption (2010), was skeptical of how a “full-length novel can be rendered in comic-book fashion” (Marton E-mail). Annie West, who wrote The Sheikh’s Ransomed Bride (2007), noticed discrepancies between her book and the manga adaptation:

My memory of the Japanese edition of Belle and Rafiq’s story is that it did seem to follow the original plot and that a lot of effort went into showing the glamour of the exotic kingdom. I did find it interesting that in the beginning Belle had her hands locked in wooden stocks rather than iron manacles, as in the story, but perhaps that was to add the feeling of this being a foreign place. (West E-mail)

West noted how the illustrator made changes to the plot and setting, highlighting how the changes further exoticized the environment. Ultimately, these authors’ responses reveal how the manga adaptation process adds yet another layer of translation to this cross-cultural product.

While Harlequin developed and tested its comics in the Japanese market, manga were becoming more popular in the United States. Sales of manga printed in the graphic-novel format began increasing in America in the early 2000s (Schwartz and Rubinstein-Ávila 41). In 2003, manga sales in the United States were estimated to be about $100 million (Reid). Publishers Weekly noted that “Manga continues to be one of the hottest categories in bookstores” in 2003 (MacDonald). In December 2004, Publishers Weekly claimed that manga had made it in the United States: “Manga is the biggest comics publishing story of the year—and also last year…No one is calling manga a fad anymore” (Staff). In 2006, Time magazine noted that women and girls comprised 60 percent of the new wave of manga readers in the United States (Masters). By the mid-2000s, manga madness had swept across America.

Harlequin comics, which featured Caucasian characters and European settings (see figure below), were well-suited for an American audience. As Ito notes, the heroines in Japanese ladies’ comics have “Miss America features—curly hair, large and round eyes with thick eye lashes (which often take about 1/3 space of the entire face!), well-shaped sexy eye brows, long nose, thin and cute lips” (“Japanese Ladies’” 71). The American market is not tolerant of foreign cultural products, so manga with “less ‘Japaneseness’” are better for transnational publication (Wong 37, 39). Thus, the character art in Harlequin’s comics was expected to appeal to American readers’ aesthetic tastes.

Sample images of Harlequin manga published in English (Pierce 2015).

Harlequin decided to take advantage of the emerging manga market in the United States. In 2005, the company entered into a licensing agreement with Dark Horse Comics to release English-versions of its comics in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia (Harlequin Enterprises Ltd). Dark Horse was responsible for translating, packaging, and distributing the Harlequin manga (Macdonald). However, Harlequin established its own manga imprint “Pink Ginger Blossom” in 2006 (Mays). Harlequin took over distribution while Dark Horse continued to translate and package the comics (Mays). Since 2006, the company has continued to release its manga adaptations in the United States.

Harlequin has also explored various digital platforms for the release of its comics in Japan and the United States. The company partnered with SoftBank Creative, the third largest mobile company in Japan, to make its comics available via mobile phone applications in Japan in 2007 (Cameron 24, “Media Release”). The Canadian Business magazine noted that, “The transfer of manga illustrations is fairly data-intensive, but because the mobile Internet is so advanced in Japan, comics can be read easily on a cellphone,” adding that, “Japanese characters make it possible to read more text on a small screen than other languages” (Cameron 24). Two years after making its manga digital in Japan, the company announced the mobile digital distribution of Harlequin comics in America through AT&T and Verizon, two American mobile service providers; its manga were also made available for Amazon’s Kindle platform in 2009 (“Media Release”). Later in 2011, the comics were released on Barnes & Noble’s Nook (Kozlowski). In tandem with the e-book revolution, Harlequin’s latest efforts have been to increase the digital availability of its manga in both Japan and the United States.

Conclusion

Since entering Japan in 1979, Harlequin has been forced to acknowledge the challenges of cross-cultural translation and adaptation. By the time that a reader in the United States picks up a Harlequin comic, the product has undergone transnational editing multiple times. First, the English novel is translated and edited into Japanese. Then, the Japanese novel is adapted into a manga. Finally, the Japanese manga is translated and edited back into English. Thus, the final product is the result of a multi-step “transediting” and adapting process. This report is the first to trace the history of this process from the 1980s to now; however, it should be noted that the report only covers the story of Harlequin in Japan through English sources, so the Japanese side of the story is yet to be told. As a cross-cultural product, Harlequin manga represent a unique case in translation and adaptation, and should therefore be the object of study for future research.

Bibliography

Bodsworth, Charles. “How Mills and Boon turned to manga comics.” BBC News Magazine, (April 12, 2004). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/3614229.stm.

Cameron, Laura. “Comical Romance is Big in Japan.” Canadian Business 83, no. 4 (Mar, 2010): 24. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/864296869?accountid=10598.

Chira, Susan. “Can U.S. Good Succeed in Japan?” New York Times (New York City, NY), April 7, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/04/07/business/can-us-goods-succeed-in-japan.html.

Devine, Carol. E-mail message to author. April 10, 2018.

Fujita, Kazuko. “The Rich, the Ruthless and the Really Handsome. Vol: 3.” Digital image. Anime Planet. 2011. Accessed March 23, 2018. https://www.anime-planet.com/manga/the-rich-the-ruthless-and-the-really-handsome.

Graham, Lynne. E-mail message to author. April 4, 2018.

—. E-mail message to author. April 5, 2018.

Grescoe, Paul. The Merchants of Venus: Inside Harlequin and the Empire of Romance. Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 1996.

Harlequin Enterprises Ltd. “Dark Horse Comics to Publish Harlequin Novels in Manga Format.” Canada NewsWire, (June 01, 2005). https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/453253248?accountid=10598.

Harlequin’s Overseas Team and Harlequin Japan. “Harlequin Books Like You’ve Never Seen Them Before.” Harlequin Blog, (November 23, 2013), https://harlequinblog.com/2013/11/harlequin-books-like-youve-never-seen-them-before/.

Ito, Kinko. “A History of Manga in the Context of Japanese Culture and Society.” Journal of Popular Culture 38, no. 3 (February, 2005): 456-475. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/195368472?accountid=10598.

—. ““The World of Japanese Ladies’ Comics: From Romantic Fantasy to Lustful Perversion.” Journal of Popular Culture 36, no. 1 (Summer, 2002): 68-85. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/195363920?accountid=10598.

Jensen, Margaret Ann. Love’s $weet Return: The Harlequin Story. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1984.

Kozlowski, Michael. “Digital Manga and Harlequin Bring Manga to the Barnes and Noble e-Readers.” GoodEReader, (August 19, 2011). https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/digital-manga-and-harlequin-bring-manga-to-the-barnes-and-noble-e-readers.

Krentz, Jayne Ann. Introduction to Dangerous Men & Adventurous Women: Romance Writers on the Appeal of the Romance, 1-9. Edited by Jayne Ann Krentz. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1992.

Macdonald, Christopher. “Harlequin Manga from Dark Horse.” Anime News Network, (June 2, 2005). https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2005-06-02/harlequin-manga-from-dark-horse.

MacDonald, Heidi. “Manga Sales Just Keep Rising.” Publishers Weekly 250, no. 11 (March 17, 2003). https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/print/20030317/22095-manga-sales-just-keep-rising.html.

Marton, Sandra. E-mail message to author. April 4, 2018.

Masters, Coco. “America is Drawn to Manga.” Time, August 10, 2006, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1223355-1,00.html.

Mays, Jonathan. “Harlequin Re-Launches Manga Line.” Anime News Network, (June 16, 2016). https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2006-06-16/harlequin-re-launches-manga-line.

McGugan, Ian. “Strangers in a Strange Land.” Canadian Business 69, no. 7 (June, 1996): 107-108. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/221335821?accountid=10598.

“Media Release: Harlequin Enterprises Limited.” MediaNet Press Release Wire. Last modified November 21, 2009. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/455268856?accountid=10598.

Momose, Natsu. “The Greek Tycoon’s Defiant Bride.” Digital image. EbookRenta. Accessed March 23, 2018. https://www.ebookrenta.com/renta/sc/frm/item/46833/.

Mortimer, Carole. E-mail message to author. April 4, 2018.

Mulhern, Chieko Irie. “Japanese Harlequin Romances as Transcultural Woman’s Fiction.” The Journal of Asian Studies 48, no. 1 (February, 1989): 50-68. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/230407343?accountid=10598.

Ogi, Fusami. “Female Subjectivity and Shoujo (Girls) Manga (Japanese Comics): Shoujo in Ladies’ Comics and Young Ladies’ Comics.” Journal of Popular Culture 36, no. 4 (Spring, 2003): 780-803. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/195365415?accountid=10598.

Ogoshi, Natsue. “The Italian Billionaire’s Bride.” Digital image. Goodreads. Accessed March 23, 2018. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/18898845-the-italian-billionaire-s-bride.

Pierce, Melinda. “Sweep Me Off My Feet!” Digital image. Women Write About Comics. April 3, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2018. http://womenwriteaboutcomics.com/2015/04/03/sweep-me-off-my-feet-next-gen-romance-comics-we-need-better/.

Reid, Calvin. “U.S. Manga Sales Pegged at $100 Million.” Publishers Weekly 251, no. 6 (February 9, 2004). https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/print/20040209/40959-u-s-manga-sales-pegged-at-100-million.html.

Schwartz, Adam and Eliane Rubinstein-Ávila. “Understanding the Manga Hype: Uncovering the Multimodality of Comic-Book Literacies.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 50, no. 1 (September 2006): 40-49. Accessed March 22, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.50.1.5.

Spencer, Jim. “Japanese Fall For Romances.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), Sept. 15, 1986. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1986-09-15/features/8603090005_1_study-of-japanese-literature-deep-throat-sales-of-romance-novels.

Staff. “Manga Bonanza.” Publishers Weekly 251, no. 49 (December 6, 2004). https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/print/20041206/28019-manga-bonanza.html.

Tanaka, Rei. “Harlequin: Romancing the Japanese Market.” Journal of Japanese Trade & Industry, no. 5 (1984): 41-43. https://www.jef.or.jp/journal/pdf/view_8409.pdf.

West, Annie. E-mail message to author. April 5, 2018.

Wirten, Eva H. “‘they Seek it here, they Seek it there, they Seek it Everywhere’: Looking for the “Global” Book.” Canadian Journal of Communication 23, no. 2 (Spring, 1998): 233. https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/219575960?accountid=10598.

Wong, Wendy Siuyi. “Globalizing Manga: From Japan to Hong Kong and Beyond.” Mechademia 1 (2006): 23-45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41510876.