Representations of Native American Heroes During the 1990s and the 2010s

By Sophia Divone (2021)

Introduction

At the 2016 RITA Awards, author Sarah M. Anderson won the Contemporary Romance category for The Nanny Plan (2015), a novella that explores the relationship between a billionaire and a Native American heroine (Romance Writers of America; GoodReads). While the novella received mostly positive reviews upon its release, the story was highly criticized by Courtney Milan, a former Director-at-Large for the Romance Writers of America, in a series of tweets in 2018. Milan argued that the novella contains problematic depictions of Indigenous characters, as it “was a book (written by a white author) where the heroine was Native and had a family history of alcoholism and poverty (because of course she did)” while “the hero was a white savior” (@CourtneyMilan, April 2, 2018). While Milan’s goal was to draw attention to broader trends of bias and racial prejudice in the romance fiction industry, her tweets shed light on the stereotyped representations of Native heroes and heroines that have persisted in U.S. contemporary romance fiction. Furthermore, she criticized Anderson’s decision to perpetuate stereotypes about Indigenous people, as this once again placed the narrative of Native characters in the hands of a non-Native author.

While Anderson’s The Nanny Plan contains an Indigenous heroine and white hero, a larger body of romance fiction novels feature relationships between white heroines and Native or mixed-race heroes. This pairing between Native heroes and white heroines can be found in U.S. contemporary romance fiction novels published in the decades after the “post-1972 historical boom” and helped to popularize stories that “depict a love affair…between a European American character (usually the heroine) and a full- or half-blood Native American” (Avery 2018; Wardrop, 61). Accordingly, popular romance fiction novels from the early-to-mid 1990s often typecast Native American heroes as sex symbols who are objects of the white heroine’s desire (Van Lent, 211; Bird, 68). Moving into the 21st century and, more specifically, into the 2010s, there appeared to be a shift from the stereotyped portrayals of Native men seen in the late twentieth century to more realistic portrayals of protagonists in both contemporary and historical contexts. While there is little scholarship on representations of Native heroes in romance fiction from the 2010s, communities of authors and readers on personal blogs and sites like Book Riot and Smart Bitches, Trashy Books have published articles featuring culturally sensitive, historically accurate romance novels with Native heroes in order to increase awareness of these books within the subgenre (Avery 2018; Smart Bitches, Trashy Books).

In this paper, I will examine the differing representations of Native American heroes in romance fiction novels from the early-to-mid 1990s and the 2010s. While existing scholarship draws parallels between negative representations of Native protagonists in seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth century literature and romance novels from the 1990s, there does not appear to be literature that evaluates recent depictions of Native heroes or that explores changes in the characterization of Native heroes in the subgenre. Through this comparison, I will explore the transition from essentialized portrayals of Indigenous heroes in commercially successful works from the 1990s to more authentic depictions of Native men in works from the 2010s. While Native heroes in romance novels published during the early-to-mid 1990s were usually one-dimensional characters who perpetuated historical stereotypes, Indigenous protagonists in romance fiction novels from the 2010s tend to be more diverse and dynamic. This shift in characterization may be attributable to the presence of more Native, or #OwnVoices, authors in the romance fiction industry.

Representations of Native American Heroes in the Early-to-Mid 1990s

Although it is difficult to pinpoint the first romance novel published within the Native American subgenre, these novels appeared to gain popularity during the 1980s and attained commercial success by the early-to-mid 1990s (Carr 2021; Lessard, 15). By the 1990s, several tropes emerged within the genre that engendered formulaic characterizations of Native heroes. While completing an informal survey of Native American romance novels published in 1990, Professor Peter Beidler discovered that each Indigenous protagonist was “almost exclusively [a] young, strong, virile, handsome ‘warrior’” who implemented his “Indian skills of fighting and tracking, and his superior knowledge of the terrain to save [the heroine] from dangers” (Beidler, 100). Here, Beidler captures three characteristics inherent to the late twentieth century Native hero, being his exotic appearance, his strong connection to nature, and his nobility of character. In tandem, these characteristics led to the creation of one-dimensional protagonists who embodied historical stereotypes of Native American men.

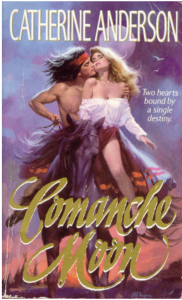

One of the defining characteristics of the Native American protagonist in late twentieth century romance fiction novels is his physical appearance, and this is one of the ways that he is fetishized and objectified in the subgenre. Scholar Peter Van Lent noted that the majority of these characters have “glistening, coppery skin and long, raven-black hair… and usually wear little more than a breechclout” (Van Lent, 214). This characterization seems to hold true when looking across commercially successful Native American romance fiction novels from the 1990s. In fact, the search query “Native American Romance Books” on Goodreads yields a series of popular titles from the late twentieth century, including Catherine Anderson’s Comanche Moon (1991) and Comanche Heart (1991), Madeleine Baker’s First Love, Wild Love (1989), and Sandra Bishop’s Beloved Savage (1990), which each depict a muscle-bound hero with tanned or darkened skin and flowing black hair (Native American Romance Books).

The cover art featured on Anderson’s Comanche Moon aligns closely with Van Lent’s characterization of the twentieth century Native hero, and her description of the male protagonist in the novel paints a similar picture, as he is depicted as having “chest and arms [of] burnished copper” and is purported to look “more like an artist’s carving than a flesh-and-blood man” (Anderson, 111). Here, the Native protagonist is not only defined by his dark skin, muscular body, and exotic appearance relative to the female protagonist, but he is also objectified. Referring to the male protagonist’s body as that of an “artist’s carving” transforms him into an idealized representation of a man, making him “an exotic, exciting, and, moreover, appropriate love-object for [the] white heroine” (Burley, 80). In effect, this narrow depiction of Indigenous protagonists as young, attractive, and exotic played a key role in creating the formulaic hero that defined the Native American subgenre during the early-to-mid 1990s.

This representation of Indigenous protagonists was likely derived from existing stereotypes about Native American men. Across popular literature from the nineteenth century, historical accounts, and even neoclassical sculpture, Native men are characterized by their physical prowess, rugged masculinity, and tendency to be nude or partially-nude (Bird, 66; Van Lent, 217). The late twentieth century romance fiction hero described by Van Lent and Beidler closely resembles this archetype, as he is virile, physically dominant, and often wears little clothing. While we cannot make generalizations across all novels in the Native American subgenre, there is evidence that historical stereotypes surrounding Indigenous men’s appearance and sexuality influenced the characterization of heroes during the early-to-mid 1990s. This may help to explain the formulaic depictions of Indigenous heroes, as their characterization seems to be grounded, at least in part, in historical stereotypes.

Beyond his physical appearance, the Indigenous hero from the early-to-mid 1990s romance fiction novel is characterized by his strong and seemingly innate connection with nature. We can see this stereotype play out in Anderson’s Comanche Moon, where the male protagonist is able to calm a rogue stallion by “speaking softly in Comanche” and “touch[ing] his lips to the stallion’s muzzle, breathing in, then out” so that “the horse inhaled, tasted, and the fear seemed to leave him” (Anderson, 104-105). After this encounter, the female protagonist concludes that “man and beast were one in a way she had never experienced, had never dreamed could be” (Anderson, 104-105). A similar scene occurs in Colleen Faulkner’s novel Forever His (1993), as the hero is able to “catch a fish without a hook or line” which he considers to be an inherently “‘Indian thing’” (Wardrop, 70). This association between Indigenous men and the natural world is exemplified in a quote from a Romance Times Magazine Spotlight article, where the author opines that “the Native American romance emphasizes instinct, creativity, freedom, and the longing to escape from the strictures of society to return to nature” (Waite 2014). While this quote emphasizes a perceived connection between Indigenous characters and nature, it also plays into a larger theme of romanticizing Native American life and culture, particularly in a historical context. By associating Native heroes with the natural world, there is an implication that these characters hailed from a simpler time that was removed from civilization (Van Lent, 211). Often, this simpler time was represented by a “traditional setting” situated in the past (Van Lent, 214). This romanticization of Native American heroes and culture reinforces the narrative of an “appealing version of the past” and perpetuates the historical misconception that times were in fact simpler in the past, which is clearly divorced from the reality of American history during the nineteenth century (Burley, 89). Using Beidler’s informal survey of Native American romance fiction novels from 1990, we can corroborate the assertion that late twentieth century Indigenous heroes were usually depicted in the past. According to the survey, fifteen out of the seventeen books studied were set during the nineteenth century, while only two of the books took place before or after the nineteenth century (Beidler, 98). While this study only evaluated a cross-section of Native American romance fiction novels and therefore cannot be applied to the subgenre as a whole, it provides evidence that Native heroes were more commonly represented in historical settings during the early 1990s. Accordingly, a common thread across Native American heroes from late twentieth century romance novels is their close relationship with the natural world and existence in a traditional setting that is usually removed from civilization. By depicting these heroes in historical settings, many of these novels perpetuate a romanticized, historically inaccurate version of the past.

The final trait that characterizes the early-to-mid 1990s Native hero is his nobility of character. This representation of the Native hero expands upon the Noble Savage trope where a hero is considered to be morally pure and noble because of his close relationship with nature instead of civilization (Van Lent, 211). In this case, the Indigenous hero serves as a foil to the white male characters in the novel, who are often depicted as greedy or immoral (Beidler, 100). While it is not clear whether this relationship between the Native male protagonist and secondary male characters is common across all late twentieth century Native American romance fiction novels, there is evidence of this dynamic in the novels of commercially successful authors like Madeline Baker and Cassie Edwards. In Baker’s Forbidden Fires (1990), the Native American protagonist Rafe is portrayed as “strong, handsome, smart, and kind” while his foil Abner is a predatory and jealous villain who attempts to bring about Rafe’s downfall (Beidler, 102). In Edward’s novel Savage Dream (1991), the male protagonist Shadow is similarly depicted as “responsible, diplomatic, and noble” because he is willing to compromise with the white plantation owners featured in the story (Beidler, 112). In addition to serving as a foil to the white characters in the novel, the hero is often differentiated from other men in his tribe who are inclined to “raid, pillage, and fight among themselves when not listening to [the hero’s] wise advice” (Bird, 70). Therefore, the protagonist is not only placed on a pedestal above the white male characters in the novel, but a distinction is made between his behavior and the behavior of other Indigenous characters in the story. Similar to the physically attractive Native protagonist, the noble Native protagonist represents an idealized man who is depicted as morally superior to the other male characters in the novel.

Overall, the Native hero featured in late twentieth century romance novels is defined by his physical appeal, his connection with the natural world, and his noble character. There is evidence that this characterization is based on historical stereotypes about Indigenous men’s physical appearance, sexuality, and behavior. Accordingly, these characters tend to be one-dimensional and are often idealized and objectified.

Changes in the Characterization of Native American Heroes in the 2010s

As we transition into the twenty-first century and, more specifically, into the 2010s, there is evidence of more diverse representations of Native American heroes in contemporary, historical, dystopian, and science-fiction settings (Avery 2018; Beautifully Bookish Bethany; Carr 2021; O’Brien 2019; Smart Bitches, Trashy Books). These stories tend to offer more realistic portrayals of Indigenous characters and often feature narratives about the characters’ “identity, heritage and community” (Carr 2021). Because of this, it is far more difficult to find commonalities across Native heroes in romance fiction novels from 2010s. While some common traits do exist, as the male protagonists in the novels that I researched focus on young adult characters, most of the similarities end there. For example, while Robin Covington’s novel Sacred Son (2018), Pamela Clare’s Tempting Fate (2017), and Silver James’s Claiming the Cowgirl’s Baby (2017), all feature young adult heroes, the heroes differ significantly in their lifestyles, goals, and socioeconomic backgrounds (Clare; Covington; James). In Covington’s Sacred Son, the protagonist Judah lives on a reservation and is focused on regaining custody of his son, meanwhile Kaden, the hero in James’s Claiming the Cowgirl’s Baby, is a ranch hand and the son of a billionaire. Despite these apparent differences in characterizations, this evidence is anecdotal, and a more thorough survey of the literature is necessary to determine if other commonalities exist across Native American romance fiction novels from the 2010s.

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort among bloggers and readers on sites like Book Riot, Smart Bitches, Trashy Books, and GoodReads to promote romance fiction novels that feature Native American protagonists who are not defined by stereotypes. In a 2019 post on Smart Bitches, Trashy Books entitled “The Rec League: Native American Romance,” a user asked for recommendations of romance novels written by Native authors. This post was met with over fifty comments suggesting novels featuring First Nation protagonists that were primarily written by Native authors. In a similar vein, Beautifully Bookish Bethany, a book youtuber with over 11,000 subscribers, recently started a virtual book club with the goal of highlighting First Nation romance novels that do not reinforce stereotypical narratives about Indigenous people (Beautifully Bookish Bethany). Her first video garnered over 900 views and has a relatively high level of engagement from viewers in the comment section, which further demonstrates an interest among bloggers and romance fiction readers in promoting stories with diverse, authentic portrayals of Native heroes and heroines.

As demand for representative depictions of Native American heroes from certain authors, bloggers, and readers increases, it is important to evaluate the factors that are driving this shift in in characterization of Native protagonists. A potential reason behind this change is the presence of more Native American, or #OwnVoices, authors in the romance fiction industry. In general, #OwnVoices authors are able to craft more nuanced, representative characters because they possess the “authority that comes with writing from lived experience” as these “author[s] share an identity with the character” (Blue Crow Publishing).

In an interview on the program Native America Calling, three #OwnVoices authors discussed the status of Native American narratives in the romance fiction industry and the ways that they combat embedded cultural stereotypes in the genre (Blackbird et al.). One of the featured authors, Malea Powell, described how her frustration with stereotypical representations of Indigenous people in romance fiction, including common tropes from the late twentieth century, provided an impetus for her to publish novels where members of her community are accurately represented (Blackbird et al.). Similarly, author Maggie Blackbird discussed how her knowledge about Christian churches on Native reservations inspired her to write a novel featuring gay protagonists (Blackbird et al.). Through this story, she had the opportunity to explore the challenges of reconciling First Nation and Catholic values, while simultaneously exploring the impact of this cultural clash on her characters’ sexual identities. Blackbird also discussed her efforts to capture the day-to-day lives of members of her community in her writing in order to demystify misconceptions about modern-day Indigenous people. Author Malea Powell agreed with this sentiment, adding that she wanted to include regular, middle-class characters in her novels as a means to combat stereotypes that categorize Native heroes as “uber warriors” or mythical people (Blackbird et al.). Meanwhile, historical romance writer Evangeline Parsons Yazzie emphasized the importance of conducting research through formal and informal networks while writing historical fiction. Despite belonging to the Navajo Nation, she did not feel comfortable writing male Navajo characters without consulting men from her community. She believed that since she “did not marry a Navajo…[she] did not know what a Navajo man would say to a Navajo woman,” which prompted her to consult “two of [her] Navajo male friends” to capture the language that they would use when courting a Navajo woman (Parsons Yazzie). In each of these instances, the authors drew from personal experience and extensive research to capture cultural nuances in their writing and create authentic, dynamic male characters. While Powell’s, Blackbird’s, and Parsons Yazzie’s efforts represent microcosmic changes in the romance fiction industry, the inclusion of more #OwnVoices writers could accelerate progress towards accurately representing the experiences of Native American men in the subgenre.

Conclusion

Native American romance novels published during the early-to-mid 1990s present stereotyped and fetishized portrayals of Native heroes centered around the hero’s appearance and sexuality, his connection with nature, and his noble character. These traits are rooted in stereotypes and perpetuate historically inaccurate ideas about Native American men and the cultural values and traditions of different Native American tribes. As we transition into the twenty-first century and the 2010s, there are an increasing number of novels within the subgenre that contain accurate, authentic depictions of Native protagonists. Given the advent of the #OwnVoices movement and the growing focus on exploring cultural identity and heritage in contemporary fiction, there is evidence that the subgenre is moving in a positive direction in an effort to avoid the stereotypical representations of Native heroes seen at the end of the twentieth century. That being said, the conflict between Sarah Anderson and Courtney Milan demonstrates the importance of holding authors accountable and educating them when they misrepresent the identity or lived experience of a Native person in their work.

Bibliography

Anderson, Catherine. Comanche Moon. HarperCollins Publishers, 1993.

Avery, Jessica. “Native American Romance Novels by Native Authors.” Book Riot, January 4,2018, https://bookriot.com/native-american-romance-novels/.

Baker, Madeline. First Love, Wild Love. Dorchester Publishing, 1996.

Beautifully Bookish Bethany. “ANNOUNCING The Indigenous Romance Readalong! | March-August 2021.” Youtube Video. February 23, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtnwMPkrA30

Beidler, Peter G. “The Contemporary Indian Romance: A Review Essay.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 15, no. 4 (January 1991): 97-126.

Bird, S. Elizabeth. “Gendered Construction of the American Indian in Popular Media.” Journal of Communication 49, no. 3 (September 1999): 61-83.

Bishop, Sandra. Beloved Savage. Zebra Books, 1998.

Blackbird, Maggie, Malea Powell, and Karen Kay. “Native romance novels.” Interview by Monica Braine. Native America Calling, Oct. 10, 2019. Audio. https://nativeamericacalling.com/Thursday-october-10-2019-native-romance-novels/.

Burley, Stephanie Carol. “Hearts of Darkness: The Racial Politics of Popular Romance.” PhD diss., University of Maryland, College Park, 2003.

Carr, Susanna. “Contemporary Native American Romances.” http://susannacarr.com/contemporary-native-american-romances/

“First Nations Love: Best Native American Leads in Contemporary Romance.” GoodReads. https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/71390.First_Nations_Love_Best_Native_American_Leads_in_Contemporary_Romance_

Lessard, Victoria. “Marketing Desire: The ‘Normative/Other’ Male Body and the ‘Pure’ White Female Body on the Cover Art of Cassie Edwards’ Savage Dream (1990), Savage Persuasion (1991), and Savage Mists (1992).” Master’s thesis, McGill University, 2017.

Milan, Courtney (@courtneymilan). “This was a book (written by a white author) where the heroine was Native…,” Twitter, April 2, 2018. https://twitter.com/courtneymilan/status/980874007137234944

“The Nanny Plan.” GoodReads. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23452705-the-nanny-plan

“Native American Romance Books.” GoodReads. https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/7107.Best_Native_American_Romance

O’Brien, Kelley. “7 Native American Romance Novels That Are Too Beautiful for Words.” Women.com. April 4, 2019. https://www.women.com/kelleyobrien/lists/native-american-romance-novels-040419

Parsons Yazzie, Evangeline. “Book of the Month: ‘Her Captive, Her Love’ by EvangelineParsons Yazzie.” Interview by Tara Gatewood. Native America Calling, July 25, 2019. Audio. https://soundcloud.com/native-america-calling/07-25-19book-of-the-month-her-captive-her-love-by-evangeline-parsons-yazzie.

“Past RITA Winners.” Romance Writers of America. https://www.rwa.org/Online/Awards/RITA/ Past_RITA_Winners.aspx

“The Rec League: Native American Romance.” Smart Bitches, Trashy Books. https://smartbitchestrashybooks.com/2019/01/the-rec-league-native-american-romance/#comments

Van Lent, Peter. “‘Her Beautiful Savage’: The Current Sexual Image of the Native American Male.” In Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture, edited by S. Elizabeth Bird, 211-227. New York, NY: Westview Press, 1996.

Waite, Olivia. “I Is For American Indians, Native Americans, First Nations, Indigenous Peoples, Etc.,” April 10, 2014, https://www.oliviawaite.com/blog/2014/04/a-is-for-american-indians.

Wardrop, Stephanie. “Last of the Red Hot Mohicans: Miscegenation in the Popular American Romance.” MELUS 22, no. 2 (Summer 1997): 61-74.

“What does #OwnVoices mean?”. Blue Crow Publishing, March 30, 2018. https://bluecrowpublishing.com/2018/03/30/what-does-ownvoices-mean/