A Sign of the Times: Forced Compromises from Publishers and the Sacrifices of Lesbian Pulp Fiction Authors

By Alexia Jackson (2022)

Introduction

After the creation of paperbacks, the publishing industry began producing high quantities of new novels and selling them for cheap. Among these new novels were lesbian pulps characterized by their “erotic sensationalism,” tragic endings, and raunchy covers.[1] The majority of lesbian pulp fiction novels were similar in plot and style because publishers followed a “formula” that guaranteed they would sell.[2] Over 500 of them were produced between 1950 and 1965; Barbara Grier, the creator of Naiad Press (the first publishing company dedicated to lesbian novels), referred to this timeframe as the “golden age.” [3] In this paper, I will argue that rampant homophobia in the 1950s resulted in censorship from both publishers and the government, which forced lesbian pulp fiction authors to compromise on the content and covers of their novels. To prove this argument, I will first address why publishers chose to influence novels’ content and subsequently identify the three main types of compromises that authors made. Then I will discuss what motivated authors to make these compromises and how this process impacted them. All claims in this paper will be substantiated by author testimonies in which they retrospectively reflect on their experiences with publishers.

Protecting Profits Against Censorship and Homophobia

Due to the prevailing societal perception of queerness as deviant in the 1950s, there were overwhelming expectations for individuals to adhere to normative standards of sexuality.[4] The United States government perpetuated these homophobic notions when they banned media that included homosexual content through the passage of the obscenity laws of the 1950s.[5] The government enforced these laws through the postal office.[6] Many notable publishers, such as Fawcett Publications, shipped large quantities of books together.[7] Given that the U.S government was inspecting packages, it was risky for publishers to include novels with homophobic content in their shipments. The publisher of Spring Fire confirmed this when speaking to author Vin Packer about these risks: “If your book appears to proselytize for homosexuality, all the books sent with it to distributors are returned.” The publisher also made it clear to Packer that they did not care about “anybody’s sexual preference;” instead, they sought to ensure the “success of the line”.[8] Thus, rather than challenge these laws and risk their entire shipment, publishers adhered to them.

Publishers passed inspections by forcing authors to follow specific content requirements, limiting authors’ “creative” expression.[9] More specifically, authors were forced to compromise on the endings of their novels. Packer’s publisher told her that the lesbian couple in her book could not have a “happy ending” and suggested that the protagonist would have to denounce homosexuality as a sin.[10] However, Vin Packer was far from the only author forced to end her books tragically. A publisher at Scott Meredith Literacy Agency told Marion Zimmer Bradley, the author of I am Lesbian, that by the end of her novel, “the lesbian must discover men and/ or come to an unhappy end” and [reaffirm] heterosexuality”.[11] These tragic conclusions allowed publishers to argue that they were warning against the dangers of homosexual behavior and hence denouncing such content.[12] Since publishers were not presenting lesbian relationships positively, they could avoid the obscenity laws and ensure that their books were easily distributed, thus securing their profits.

Another reason publishers forced authors to alter their endings was to avoid displeasing the heterosexual masses. March Hastings explained that since “same-sex affection” was not acceptable in “mainstream” society, editors at Beacon forced authors to “tack on an ending of misery, punishment, sadness” to their novels. She expanded that these tragic endings were a result of “commercial influences” within the publishing industry and that the requirement was made “loud and distinct” to authors.[13] Ann Bannon, also known as the “Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction”,[14] also attested that the endings of her novels fell victim to the expectations of the heterosexual public. She disclosed that her novels’ endings were the by-products of the “biases” and “flaws” of the 1950s.[15] Publishers feared their profits would suffer if heterosexual readers thought they supported the deviant behavior of lesbians. Hence, they forced authors to alter their endings by denying their characters happiness.

Profiting Off of Straight Men

During the 1950s, the general public became increasingly interested in homosexuality after “lesbian and gay communities” grew in major cities, and studies claiming that “homosexual activity was widespread in the American population” emerged.[16] Publishers monetized this new interest by altering novels’ cover art and including erotic content catered toward straight men. A cover artist explained that during the golden age, the publishers did not care if the cover art was an accurate representation of the book’s plot. He recalls one editor telling him not to stress over the plot, reassuring him that they would instead change the plot to match the cover. Editors wanted him to focus on showcasing perfect breasts and “[making] ‘em round.”[17] In the publishing of lesbian pulp fiction novels, the experience of this cover artist would be considered the industry norm. When designing the cover art, publishers intended to appeal to “a straight male readership” by following a “formula” of women with “full round breast[s],” “narrow waist[s],” and “round hips.” This formula resulted in covers having a highly enticing and standardized look.[18] Covers that emphasized the female body and disregarded novels’ plots are clear examples of publishers capitalizing on straight men’s fetishization of lesbianism.

While reflecting on the publishing process of her novels, Marion Zimmer Bradley, the author of I am a Lesbian, confirmed that the industry focused on the straight male audience. She explained that editorial changes fed into the desires of “the drooling male,” also known as “the on-handed reader”.[19] Additionally, Ann Bannon, a famous pulp fiction author, echoes a similar sentiment to Bradley, explaining that she had no control over her covers. They were “clearly intended to appeal to the large male readership and not the lesbian constituency.” She explained that publishers utilized a “clever representation of the female gender” to provide “an incentive” to straight men to “buy the book.”[20] Publishers made it clear to authors that even if lesbian relationships were central to these novels’ plots, lesbians were not the prioritized audience. Instead, publishers centered heterosexual men in their publishing process and consequently forced lesbian pulp authors to compromise on the cover art of their novels.

Publishers believed that indulging the desires of straight men would guarantee the success of lesbian pulp fiction novels. Provided that lesbians accounted for a mere six percent of the total population in the 1950s,[21] publishers knew they needed to appeal to a broader audience in order to sell large quantities of these novels. Ann Bannon attests that lesbian pulp authors “cared intensely about the effect the cover designs would have on the readership.” Still, the editors focused “on something more practical: how to move their inventory.”[22] When Spring Fire was republished in 2004, the author, Vin Packer, remembered a similar sentiment from her publisher. She recalls her publisher told her they needed “to jazz up the title and wrap it in a sexy cover” because, at the end of the day, “this [was] a business.”[23] Packer’s publisher made it clear that these novels needed to be profitable and to do so, they needed to have visual appeal. At this point, lesbian relationships were only acceptable when they appealed to men’s desires and were profitable.

Retaliating Against Representation Through Cover Art

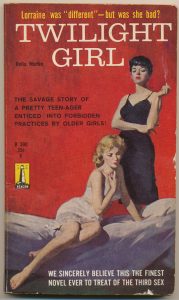

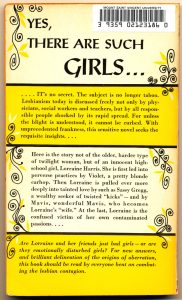

The covers of these novels were not only designed to appeal to men but also were meant to discredit the authenticity of these books. Books that appealed to lesbian readers with “more honest” plots were typically accompanied by covers that “moralized” against these stories.[24] A key example of this phenomenon is Twilight Girl by Della Martin. The cover features two women with small waists and accentuated breasts wearing silky nightgowns with lace. The more masculine-presenting character is looked down upon, the more feminine one dressed in all white.[25] However, this novel’s reviews and back cover text tell a more complex story beyond these women’s sex appeal. The back cover begins with an assertion that “the subject [lesbianism] is no longer taboo” and claims that this novel has “unprecedented frankness” with “requisite insights.”[26] According to a review by Barbra Grier, the novel followed through on these promises describing it as an “unusually intuitive book.”[27] The story achieved this authenticity by “[raising] important questions about the nature of what it is to be a lesbian.”[28]

The stark contrast between the seductive nature of novels’ covers and the quality of lesbian representation in the plots confirms the disconnect between the authors’ intent and the publishers. This disconnect is confirmed by Bannon when she explained that the industry was disingenuous with novels’ cover art while authors simultaneously attempted to offer readers honest representation.[29] Unfortunately, the climate of the 1950s discouraged this type of representation, so authors compromised and accepted what they were offered. A different author, Vin Packer, explained that she agreed to these types of compromises because authors were “informed by the times.”[30]

Lesbian Pulp Fiction Authors’ Motivations

Pulp fiction authors agreed to publishers’ changes for various reasons, including money, representation, and acceptance. Monetary incentives and literary success were common factors that influenced authors. Marion Zimmer Bradley explained that “if she hoped to get paid, she had to stick to” her publishers’ plot. She revealed that she put up with this because she was “young,” “starry-eyed about writing,” and couldn’t afford groceries.[31] Many popular authors faced income insecurity, which led them to comply with the industry’s publishing rules. Their lack of wealth minimized their power and left them vulnerable to publishers’ demands.

Another reason that authors agreed to publishers’ demands is because of their desire to express their sexual identity and increase lesbian representation in the industry. Many of the popular authors “were women who used the conventions of the lesbian paperback to express their own lesbian identities.”[32] These women wanted better representation for both themselves and other lesbians. Author Ann Bannon explained that lesbians felt “uniquely alone” in the fifties without anyone to relate to. She attests that lesbian pulps weren’t always the “perfect reflection” of the lesbian community, but they did allow lesbians to start “[connecting] with others.”[33] The author of Spring Fire, Vin Packer, also recognized the importance of representation in the 1950s. She explained that the publishing process forced lesbians to make compromises, but they did what was necessary to “[begin] recording [their] history.”[34] Lesbian pulp fiction authors ensured that lesbians’ experiences were represented in the media regardless of the public’s prejudice. The authors’ sacrifices to achieve representation did not go unnoticed by the lesbian community. Packer recalls that “fan mail came from women all over the United States.”[35]

Some authors accepted publishers’ changes because they hoped that their novels would lead to society accepting lesbian relationships. Carol Hales, the author of I am Lesbian, told a lesbian magazine called The Ladder that she “agreed to give the publisher overt sex scenes IF” she could push her agenda. Hales wanted her readers “to gain understanding and tolerance for Lesbians.”[36] Another pulp author who had similar goals was Paula Christian, who told an LGBTQ newsletter that she was “trying to reach [her] family with” her novels in hopes of them coming to “understand” and “accept” her. Unlike other authors, Christian claimed her “intended market was the straight populations.” She wanted to persuade them “to stop discriminating against” lesbians.[37] Christian said she was successful in this goal, considering that men “who had little or no conception of Lesbianism” reached out to her after reading her novels. Heterosexual men told her they now understood lesbians and thought they should have the “right to live their lives without interference.”[38]

Conclusion

The widespread homophobic sentiment of the 1950s led to publishers requiring lesbian authors to alter the content and covers of their books significantly. These compromises robbed the lesbian community of happy endings and accurate media representation. Irrespective of this discrimination, these authors still managed to make money, create representation for lesbians, and change the minds of some of their readers.

Appendix

Martin’s Twilight Girl Original Cover (1961)

Endnotes

[1] Anastasia Jones, “Lesbian Pulp Novels, 1935-1965,” Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library (blog), February 23, 2009, https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/article/lesbian-pulp-novels-1935-1965.

[2] Yvonne Keller, “‘Was It Right to Love Her Brother’s Wife so Passionately?’: Lesbian Pulp Novels and U.S. Lesbian Identity, 1950-1965,” American Quarterly 57, no. 2 (2005): 395, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068271.

[3] Ibid., 388.

[4] George Cotkin, “‘Carol’ and What It Was Really Like to Be a Lesbian in the 1950s,” Time, December 10, 2015, https://time.com/4141709/feast-of-excess-excerpt-carol/.

[5] Elizabeth Glazer, “When Obscenity Discriminates,” Northwestern University Law Review 102, no. 3 (2008): 1400, https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/107.

[6] Ibid., 1398.

[7] M.E. Kerr, “The Writing Life,” Lambda Book Report 7, no. 5 (December 12, 1998), https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A54140576/CPI?u=duke_perkins&sid=summon&xid=708c5f13.

[8] Vin Packer, Spring Fire (San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2004), vi.

[9] Allyson Miller, “Postwar Masculine Identity in Ann Bannon’s I Am a Woman,” University of Missouri Columbia, (January 2009): 48, https://doi.org/10.32469/10355/6476.

[10] Packer, Spring Fire, vi; Nicola Luksic, “Authors Look Back at the Heyday of Lesbian Pulp” (includes an interview with Marijane Meaker), Xtra Magazine, August 3, 2005, https://xtramagazine.com/culture/authors-look-back-at-the-heyday-of-lesbian-pulp-23687.

[11] Eric Garber, “Those Wonderful Lesbian Pulps: A Roundtable Discussion,” San Francisco Bay Area Gay and Lesbian Historical Society Newsletter 4, no. 4 (1989): 4, https://find.library.duke.edu/trln/UNCb9243805.

[12] Jay Zimet, Strange Sisters: The Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969 (Viking Studio, 1999), 22.

[13] Katherine Forrest, Lesbian Pulp Fiction: The Sexually Intrepid World of Lesbian Paperback Novels 1950-1965 (San Francisco, CA: Cleis Press, 2005) xiv, https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C1860248.

[14] Miller, “Post War Masculine Identity,” xviii.

[15] Ann Bannon, foreword to: Strange Sisters: The Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969, by Jay Zimet (Viking Studio, 1999), 21.

[16] Kathryn Campbell, “‘Deviance, Inversion and Unnatural Love:’ Lesbians in Canadian Media, 1950-1970,” Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender,Culture & Social Justice 23, no. 1 (October 1, 1998): 128, https://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/view/1699.

[17] Lee Server, Over My Dead Body: The Sensational Age of the American Paperback, 1945-1955 (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994), 64.

[18] Miller, “Post War Masculine Identity,” 6.

[19] Garber, “Those Wonderful Lesbian Pulps,” 4.

[20] Bannon, Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 9,12.

[21] Cotkin, “‘Be a Lesbian in the 1950s.”

[22] Bannon, Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 10.

[23] Packer, Spring Fire, vi.

[24] Forrest, Lesbian Pulp Fiction, xvi.

[25] Della Martin, Twilight Girl (Universal Publishing and Distributing Corp, 1961).

[26] Ibid.

[27] Barbara Grier, “Lesbiana,” Ladder, August 1961, https://archive.org/details/sim_ladder_1961-08_5_11/page/22/mode/2up.

[28] Forrest, Lesbian Pulp Fiction, xiv.

[29] Bannon, Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 14.

[30] Packer, Spring Fire, vi.

[31] Katherine Forrest, “Interview with Ann Bannon,” Lambda Literary, February 1, 2002, https://lambdaliterary.org/2002/02/interview-with-ann-bannon/.

[32] Garber, “Those Wonderful Lesbian Pulps,” 4.

[33] Bannon, Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 15.

[34] Packer, Spring Fire, vi.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “I am a Lesbian,” Ladder, January 1959, https://archive.org/details/sim_ladder_1959-01_3_4.

[37] Garber, “Those Wonderful Lesbian Pulps,” 4.

[38] “I am a Lesbian,” Ladder.

Bibliography

Campbell, Kathryn. “‘Deviance, Inversion and Unnatural Love:’ Lesbians in Canadian Media, 1950-1970.” Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice 23, no. 1 (October 1, 1998): 128. https://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/view/1699.

Cotkin, George. “‘Carol’ and What It Was Really Like to Be a Lesbian in the 1950s.” Time, December 10, 2015. https://time.com/4141709/feast-of-excess-excerpt-carol/.

Bannon, Ann. Foreword to: Strange Sisters: The Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969, by Jay Zimet. Viking Studio, 1999.

Forrest, Katherine. Lesbian Pulp Fiction: The Sexually Intrepid World of Lesbian Paperback Novels 1950-1965. San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2005. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C1860248.

Garber, Eric. “Those Wonderful Lesbian Pulps: A Rountable Discussion.” San Francisco Bay Area Gay and Lesbian Historical Society Newsletter 4, no. 4 (1989): 4. https://find.library.duke.edu/trln/UNCb9243805.

Glazer, Elizabeth. “When Obscenity Discriminates.” Northwestern University Law Review 102, no. 3 (2008): 1398,1400. https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/107.

Grier, Barbara. “Lesbiana.” Ladder, August 1961. https://archive.org/details/sim_ladder_1961-08_5_11/page/22/mode/2up.

Jones, Anastasia. “Lesbian Pulp Novels, 1935-1965.” Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library (blog), February 23, 2009. https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/article/lesbian-pulp-novels-1935-1965.

Keller, Yvonne. “‘Was It Right to Love Her Brother’s Wife so Passionately?’: Lesbian Pulp Novels and U.S. Lesbian Identity, 1950-1965.” American Quarterly 57, no. 2 (June 2005): 388,395. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068271.

Kerr, M.E. “The Writing Life.” Lambda Book Report 7, no. 5 (December 12, 1998). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A54140576/CPI?u=duke_perkins&sid=summon&xid=708c5f13.

Ladder. “I am a Lesbian.” Ladder, January 1959. https://archive.org/details/sim_ladder_1959-01_3_4.

Luksic, Nicola. “Authors Look Back at the Heyday of Lesbian Pula” (includes an interview with Jarijan Meaker). Xtra Magazine, August 3, 2005. https://xtramagazine.com/culture/authors-look-back-at-the-heyday-of-lesbian-pulp-23687.

Martin, Della. Twilight Girl. Universal Publishing and Distributing Corp, 1961.

Miller, Allyson. “Postwar Masculine Identity in Ann Bannon’s I Am a Woman.” University of Missouri Columbia, (January 2009): xviii,6,48. https://doi.org/10.32469/10355/6476.

Packer, Vin. Spring Fire. San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2004.

Server, Lee. Over My Dead Body: The Sensational Age of the American Paperback, 1945-1955. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994.

Zimet, Jaye. Strange Sisters: The Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969. Viking Studio, 1999.

For Further Reading