No Lesbian Left Alive: Unhappy Endings, Pulp FIction, and the Golden Age of Lesbian Pulp through the History of Gold Medal Books, 1950-1965

by Nicole Lindbergh (2019)

The sixth decade of 20th century America was a world in black and white, defined by harsh political dichotomy. On the one hand, the 1950s was the decade where another generation of boys was shipped to stop communism in Korea, the Senate Subcommittee of Investigations ravaged Capitol Hill in its hunt for “communists and cocksuckers,” and the American family retreated to tight-lipped and straight-laced suburbia to enjoy a society that exploded with new consumer goods while the threat of nuclear annihilation hung over their heads (Cuordoleone 515). On the other, desegregation and postwar sexualization challenged and defied the American conscious, diversifying public spaces and prompting harsh censors. An era defined by “deep-set anxiety,” it could not have been a more dangerous time to be gay, communist, or otherwise ‘un-American’, and yet a reader could walk to their drugstore and purchase a novel about lesbian romance off the book rack of any grocery store for 25 cents (Keller 180). This paper seeks to explore this phenomenon through the history of Gold Medal Books, a line of paperback originals published by Fawcett Publications from 1949 to 1965 that specialized in raunchy, low-brow fiction, in which lesbianism was a prominent theme. All and all, between 1950 and 1965, two thousand lesbian-themed mass-market books escaped McCarthy-Era government censors to bookstores across America with enormous success, with the most popular pulps selling as many as five million copies in their first editions alone, initiating what contemporary LGBT scholars call the “Golden Age of Lesbian Pulp” (Stryker 61). This paper will prove that Gold Medal Books was significant in creating both a genre that exploited lesbianism while making formative queer content more accessible than ever before as well as an entirely new type of book that ignited a paperback revolution that challenged the American conscious’s understanding of sexuality. I will do this by analyzing the first two major lesbian-themed paperbacks of Gold Medal Books, testimonies from Gold Medal Books authors, and the covers of major Gold Medal work.

Meet the Fawcetts

Fawcett Publications inadvertently started the second wave of the paperback revolution and the mass-market lesbian pulp genre in the year 1950. Up until then, Fawcett Publications was a publishing house dedicated to pulp magazines; Fawcett got their start in 1939 with the success of their star series, Captain Billy’s Wiz Bang, the pulp magazine that would eventually become comic book series Shazam!, eventually, growing to dominate the pulp magazine market with women’s magazines geared towards marital health. Not satisfied with just periodicals, however, namesake Wilford Fawcett started to expand into books and hardcovers when a contracting spat with the publishing house’s distribution company, Signet, limited the amount of paperback reprints of original hardcovers Fawcett could produce, forcing them to rely on other houses for reprints (Zimet 19). Not to be deterred, editors at Fawcett with an ingenious contract loophole: if the house couldn’t produce reprints from hardcover, then publish its original books exclusively in paperback. This simple solution had an additional benefit. To protect the impressionable American public, the Senate Committee on Pornographic Materials reviewed and censored hardcovers to ensure their moral quality. Paperbacks were not subject to this harsh external review and free from censorship. After publishing two magazine pulps as paperback originals (PBOs) without complaint from Signet, Fawcett established a new line of PBOs that would focus on taking advantage of this exemption: Gold Medal Books.

This newly minted book publisher sent shockwaves both within the industry and throughout American society by ignoring conventional industry rules and publishing scandalizing content. Gold Medal’s paperback original brought their prices for books down to a mere 25 cents and undermined the traditional royalty structure of publishing houses, giving the entire royalty to authors instead of splitting 50/50 between author and agency (“Paperback Originals”). All of the sudden, a reader could access cheap, accessible, and unregulated entertainment “out of reach—briefly—from censors,” and writers could publish content without fear of censorship in a medium that, while scoffed at by other houses as low-brow, throwaway fiction, was incredibly accessible to new writers starting out in the industry (Nealon 748; Foote 170). As one historian puts it, the lesbian pulp genre was in this way the byproduct of the 1950s paperback revolution in which “hack writers of all stripes turned out tales of sex and violence in huge quantity, falling into a variety of subgenres—teen drug abuse, white slavery, murder mysteries—of which ‘lesbian lust’ was among the most successful” (Nealon 747). Gold Medal Books’ chief editor Ralph Diagh boasted to his dumbfounded colleagues that first four mystery pulps sold 9,020, 645 books in the first six months of publishing (“Paperback Originals”). Through the line had earned the jealousy and disdain of peer houses, Gold Medal Books was poised to take advantage of the lack of censorship and the growing postwar readership through its affordability and its writers’ willingness to engage in taboo subjects.

Building the First Lesbian Pulp

While novels about lesbians such as the infamous 1928 classic The Well of Loneliness existed before the trend, the breakout novel that jumpstarted the lesbian pulp genre was Women’s Barracks, published under Gold Medal Books in 1950 (Keller 388). When she wrote it, first-time writer Tereska Torres hadn’t set out to produce a genre-creating classic with her women in wartime narrative; Torres had “intended [it to be] more broadly as a novel about women in wartime, a piece that depicted life in World War II as she remembered it during her own career in the French Freedom Army: “the vulgarity, the love, the vice, the alcohol, amidst the bombardments, the death, the strained nerves” and also the homosexual relationships unchaperoned women enjoyed away from the company of men (Stryker 49; Independent 31). The story was adapted from Torres’ personal diary and featured six homosexual and bisexual women sequestered in the women’s barracks of a French camp. At her husband’s urging, she repurposed it into a novel. When Torres’ husband delivered her first manuscript to editors at Gold Medal, they drooled at the prospect of publishing more pulp with an entirely new shocking theme. The publishing house agreed to make Women’s Barracks its fifth PBO on two conditions: as long as Torres added a narrator whose heterosexual scrutiny and scathing internal monologue would clearly signal to readers the house’s disapproval at homosexuality, she could publish (Independent 31). No one expected it to become rapidly Gold Medal’s most successful PBO, selling 2.5 million copies in its first run alone, almost a quarter of the house’s sales for that year (Keller 389).

The cultural effect of Women’s Barracks was immediate and incredible, for all Americans, but especially lesbians. Leering from the painted cover of Torres’ novels, the woman-loving women of Women’s Barracks brought the word lesbian to the American mainstream like never before, even if Torres years later scoffed that only two of them were “real lesbians” and the rest were bisexual (Independent 31). The avenues for lesbian desire or even straight curiosity were purposefully non-existent in McCarthy-Era America. Libraries were inaccessible places for queer content. “Only professors, doctors, psychiatrists, and lawyers for the criminally insane could see [library books about gay people],” remembers one lesbian Judy Grahn, and many libraries carried only limited amounts of ‘questionable’ content (Keller 394). If a library did have homosexual-related content at all, it was locked behind a cage, where only people with a Christian reason could request it (Foote 176). Passet’s survey of five rural Midwestern communities’ library acquisition records pre-Stonewall revealed that queer literature in rural libraries especially was almost non-existent. Prior to 1920, five libraries had only four novels, and by the 1950s, they had acquired only 26 more, and the books they did acquire were “as closeted as the characters they described” (Passet 753; Passet 758). If a reader in the 1950s wanted to find lesbian romance, their only option suddenly had manifested on the drugstore bookracks across the country, for once unlocked and accessible for only 25 cents.

Making a Phenomenon a Genre

Together, Torres and Gold Medal had lit a match, but it took an avalanche of reprints and another Gold Medal Book to start a fire. Uncovering the formula for what made Women’s Barracks so successful was difficult for editors convinced by an aggressively heterosexual society that lesbians were a fringe, diseased group and not a viable market on its own. To their credit, “as far as the publishers were concerned, the identities of the readers were determined by the books they had bought previously and nothing else,” but the formula for a classic lesbian pulp was still elusive (Miller 51). After Torres’ debut novel survived a fierce Senate censorship scourging and entered another round of reprints in 1951, other publishing houses flooded drugstore bookracks with a wave of pulp-sized classic “cliterature” reprints, lesbian-themed novels that had evaded public censorship in their first editions by being marketed as high culture classics, designed to test the appetite of the American pulp consumer (Zimet 90).

The results of this test were conclusive. Avon and Bantam Books knew that Radcliffe Hall’s landmark 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness, Alphonse Daudet’s 1884 Sappho, Lilyan Brock’s 1935 Queer Patterns, and Gale Wilhelm’s 1935 We Too Are Drifting were all popular books—once repackaged with cover art in the same salacious, sexy style as Women’s Barrack to masquerade as pulp, these publishers learned how important the cover was to selling gay pulp to America (Stryker 52). The Well of Loneliness in its 1951 reprint sold more than 100,000 copies a year up until the 1960s, and Claire Morgan’s Bantam Books 1952 print The Price of Salt sold more than 500,000 in its first edition alone (Keller 400). If the windfall generated by Women’s Barracks had not convinced Fawcett editors to publish more lesbian pulp, this avalanche of repackaging gave the industry the confidence it needed to produce original content. Next, Gold Medal Books just needed a new author to write a new manuscript.

Gold Medal found their author in one Marijane Meaker, a young closeted lesbian. Having always dreamt of being an author and written several short stories, Meaker started out at Fawcett Publications as a reader for Gold Medal Books, working with the editors and authors to talk through stories in story-build meetings. At one of these meetings in 1951, Meaker happened to mention one of her own personal short stories about two girls in boarding school, and catching the attention of the precipitous Irish editor Dick Carroll. Informed by the wild success of Women’s Barracks, Carrol sat down the young Marijane and cut straight to the chase: did she know any lesbians or see any lesbianism in her life? “I said, ‘Sure,’” Meaker remembers, “a lot more of it at my sorority in college” (Server 205). The next question was more overt. How would she like to write about them? It was the break that Meaker had dreamt of, the opportunity to write about lesbians as a published author. The only catch to the deal was, as Carroll insisted, no happy endings. Lesbians had to go crazy, go straight, or die by the end, or the publishing house would be accused of degeneracy by the Senate Committee of Pornographic Materials, which Torres’ Women’s Barracks had only narrowly escaped after qualifying its portrayal of lesbians with a dour ending a year before (Server 205). Within one year, Meaker had published her first book, Spring Fire, under the masculine nomme de guerre Vin Packer about reluctant, masculine leaning lesbian Mitch and queen bee Leda’s college love affair, sending shockwaves through the industry. Unlike Women’s Barracks, where women unchaperoned and under duress turned to lesbianism to relieve wartime-related stress, Mitch and Leda’s casual college tryst occurred in everyday America.

Vin Packer’s Spring Fire turned the Women’s Barracks phenomenon into a genre. Shocking publishers across genre, Spring Fire published 1,463,917 copies in its first edition alone, raking in another huge windfall for the fledgling Gold Medal Books (Keller 389; Abate 271). Even this number is conservative; Publishers Weekly’s records only included sales at traditional bookstores, ignoring other paperback distribution networks like newsstands, grocery stories, and drug stores, which pre-Stonewall lesbian oral histories reveal were frequent sources for young lesbians to look for pulp (Keller 389). If Torres had sparked publisher curiosity about lesbian-themed pulp, Packer ignited a hunger for lesbian-themed paperback originals across a plethora of publishing houses, as Lion, Bantam, and Avon began publishing regular original content about lesbian relationships within months of Spring Fire’s run (Zimet 20).

Women’s Barracks was Fawcett’s first bestseller in the same way that My Sister, My Bride, another lesbian pulp, built Bantam books; Spring Fire, Women’s Barracks, and My Sister, My Bride firmly established lesbianism as a legitimate “sales tactic in an industry that marketed women’s sexuality in a number of forms. Lesbian sex would sell a crime novel, a southern gothic, a medical text and a novel specifically about a lesbian relationship” (Miller 50). Who they were selling that sex too mattered little to anyone at Gold Medal Books—it was assumed that straight men were reading it as softcore porn— until fan mail began pouring in. Meaker claimed in a 2011 interview that Spring Fire “was not aimed at any lesbian market [at the time] because there wasn’t any that we knew about…[Torres] wasn’t aiming [Women’s Barracks] at any market either—just telling her experiences the best she could.” In fact, Meaker recalls, “we were amazed, floored, by the mail that poured in. That was the first time anyone was aware of the gay audience out there,” inspiring her to write romance fiction for the audience of women who were just like her (Keller 380). Other writers of lesbian pulp inspired by Meaker’s own success, the majority of them men, did not feel the same duty. Thus a new dichotomy evolved surrounding lesbian pulp from Women’s Barracks on, creating a so-called “industry within an industry” as straight men created pornographic pulp for other straight men while an inner core of women and lesbian writers produced less exploitative fiction for other female readers. Keller separates the genre pulp from Women’s Barracks to 1965 as either “pro-lesbian pulp” or “virile adventures”. The former involve women’s stories of love and romance from women’s point of view, usually avoiding graphic sex and the obligatory male heterosexual character that ‘fixes’ the lesbians at the end; the latter allows the two to dominate the narrative, making the lesbian pulp more palatable to male voyeurism (390). Over the next fifteen years, over a hundred male writers would produce almost two thousand hack lesbian pulp novels; fifteen women would produce less than one hundred lesbian romances in the same genre (Stryker).

These trends were all firmly established with these first two Gold Medal pulps. With Women’s Barracks and Spring Fire, Fawcett editors established three main rules to publishing lesbian fiction. First, no lesbian that refuses to return to heterosexual normalcy could have a happy ending. Second, any lesbian pulp needed a cover with salacious cover art that firmly marks it as adult fiction and beckons the voyeuristic male gaze. Third, the reader was assumed to be a straight male, period, even if the avalanche of incoming lesbian fan-mail hinted otherwise. Lesbian-themed pulp could be defended as soft-core pornography or intellectual curiosity, but lesbian-pulp for the sake of lesbian readers was indefensible during Lavender Scare censors. In the span of two books, Gold Medal Books had created a genre and defined its rules; the remainder of this paper is dedicated to analyzing how writers and readers responded to these limitations within the publishing house and outside it.

The Cover: Beckoning Men and Branding Women

Gold Medal Books created a novel approach to book faces that completely shifted the role of covers in bookselling, particularly lesbian-themed bookselling. Decades before, the politics of choosing a cover for lesbian-themed books was designed to mask the lesbian content and dress it as literature. If an author could qualify their novel as “artistic rather than pornographic,” it could possibly survive the brutal government censor (Miller 41). Other editors took this strategy seriously. When Jonathan Cape published his second edition of The Well of Loneliness in the 1930s, he hiked the price and packaged the book in a plain, expensive cover to market the lesbian-themed romance as “high culture production, rather than obscenity” (Miller 42). Women’s Barracks’ knowing glances between undressed women rejected and reverted this trend. Suddenly, the lesbian pulp became a book defined by its cover, most remarkable for its distinctive, sensationalist cover art that “telegraph its lesbian content” through its exploitative depictions of scantily clad women and brand the book with overt titles and its overt cover text, despite the chagrin of the pulp writers themselves. As future Gold Medal Books author Ann Bannon later lamented, “authors were the last people consulted by the editors about pulp fiction covers, and probably for good reason” (Zimet 10). The brooding, scantily clad women that lounged across the cover bore little resemblance to the characters in the book, but the editors and later the readership themselves recognized their important markers.

While some lesbians sneered at the books for their attempts to tantalize straight men with their covers and blurbs, many women admitted to viewing the covers both seriously and ironically. These easily identifiable markers constituted “the closest thing to a Dewey decimal system for dykes” available in the 1950s and communicated to straight audiences and lesbian readers alike the pulps’ content. In this way, the leers of the cover’s women served as both an advertisement and gay North Star, beckoning the straight reader to delight in lesbian decadence and leading the gay reader to much needed representation (Keller 392). The carefully chosen covers were “the products of the publishers,” historian and pulp writer Lee Server writes, “[but] the cultural acceptance of pulp displaying more sex and exhibitionism than were featured in mainstream novel covers before—or since—is not just about capitalism, publisher’s bottom lines, and the postwar sexualization of the marketplace, but about the publishing industry’s ability to avoid the censorship that kept Hollywood, the ‘respectable press,’ television, and radio more sanitized’” (Keller 393). The pouting beauties on the front of pulp fiction covers then communicated important if problematic messages to the lesbian observer in particular. As lesbian pulp reader and future Gold Medal Books pulp writer Ann Bannon remembers,

“If there was a solitary woman on the cover, provocatively dressed, and the title conveyed her rejection by society or her self-loathing, it was a lesbian book. If there were two women on the cover, and they were touching each other, it was a lesbian book…and if a lone male, whether looking embarrassed, hostile, or sexually deprived, appeared with two women, you had probably struck gold. Perhaps even more than the cover illustrations, the titles were classic giveaways, my own included. Women in the Shadows, Odd Girl Out, and even worse, I Am a Woman in Love with a Woman: Must Society Reject Me? (We weren’t allowed to choose our titles, either.) But as bad as they were, the titles did signal the content” (Zimet 13).

Even though the covers embarrassed and humiliated, they were formative. As Miller succinctly summarizes, “one might hate the book, love the book, identify with it or against it, but in all these cases it fosters a lesbian identity and this is perhaps the danger of the mass-produced text” (Miller 55).

No Lesbian Left Alive: Readers and Weepers

Gold Medal Book’s impact on lesbians across the country cannot be overstated, as female readers balanced the risk of being caught with the incriminating pulp with their innate desire to see themselves represented in fiction. The cover alone branded each book as highly sexual gay content; the particular challenge of “surviving the smirk” as one lesbian pulp reader called it—avoiding friends and familiar faces on the way to the cash register—required both finesse and courage (Zimet 13). “No matter how embarrassed and ashamed I felt when I went to the cash register,” working-class NY black lesbian Donna Allegra remembered, “I needed [the pulps] the way I needed food and shelter for survival” (Keller 385). Another lesbian Ann Bannon expanded on this bone-deep need:

“The majority of the establishment was against you. The federal government made your identity illegal, the medical establishment told you that you were sick and you just weren’t trying hard enough to get well…what we had were the gay and lesbian bars and the pulps. Personal contact sustained people” (Johns 73).

The aggressive heteronormativity made lesbianism invisible outside of bars and pulp. By 1960, 95% of adults in North America had been or were currently married, and by 24, 65% of white women were married (Carter 594). Existing outside of marriage, even without being queer, was a potentially dangerous choice, as single persons risked being perceived as mentally sick and thus having concerned family members put them through ‘treatment’. A 1957 survey revealed that four out of every five Americans believed that a failure to get married reflected a moral failure, or at least that said person was sick and needed painful, punitive treatment (Carter 594).

Although the danger of visibility precluded the ability of women to form communities based around their reading and made pulp reading an inherently individual experience, lesbian readers formed relationships with authors they admired. Out of the 2000+ lesbian-themed pulps and 100+ writers from 1950 to 1965, only 15 of those authors were lesbian women, the others primarily straight men writing pornography; needless to say, the pulps written by lesbians were less exploitative of the female form and resonated more deeply with lesbian readers. Meaker’s Spring Fire had a particular impact on one reader in particular, a young lesbian named Ann Bannon. “I wasn’t 100 percent sure when I picked that book up off the drugstore counter, but it was clear from the cover art and the blurb what it was about…I wrote to [the author] through Gold Medal Books, and miraculously she wrote back” (Johns 73). Charmed by her fan letter, Meaker and Bannon struck an immediate report, prompting Meaker to connect the fledgling writer with her editor, Dick Carroll, that same “colorful Irishman…with a history of screenwriting and drinking” who had published her first novel (Foote 179; Server 205). Bannon eventually enjoyed remarkable success as the so-called “queen of lesbian pulp” for Beebo Brinker Chronicles, a series of seven pulps that followed the life of the butch lesbian Beebo. Ann Bannon confessed in 2011 that “not even in [her] wildest dreams” she imagined her pulps would have such a tremendous effect on lesbian readers. “I, like most of the others back then, was convinced that we were writing throwaway fiction.” Writing the pulps was her way of surviving her heterosexual marriage as a lesbian. “I learned to live a life between my ears,” she confessed in a 2011 interview. “I did a lot of living through the books” (John 73). For both writer and reader, the pulps were an important avenue for escape from a deeply homophobic society, one that allowed readers to experience the love they were denied.

The Point of the Pulps

For straight readers and lesbian readers alike, the lesbian pulp genre and the paperback revolution that Gold Medal Books had instigated with the publishing of Women’s Barracks revolutionized the way people considered homosexuality during the 1950s, namely by exposing people to the fact that it existed at all. Through straight voyeurism, especially in the pulps where the point of view was through conflicted lesbian heroines, lesbian romances turned the villainous and diseased homosexual archetype from McCarthy’s witch hunts into “an eroticized and safe incarnation of a threatening other” (Keller 177). More so, despite the genre’s exploitation of lesbianism, the pulps “put the word lesbian in mass circulation as never before” by taking lesbian prints out of the forced invisibility of the closeted American libraries and making the previously taboo existence of queer people accessible on bookshelves across the country, connecting separated lesbians to a greater sense of identity (Keller 387). In fact, the pulps were quickly becoming an essential component of the pre-Stonewall lesbian literary diet, so much that the young Joan Nestle, future lesbian author, deemed the pulps essential “survival literature” (Carter 585; Keller 386). Lesbian readers formed periodicals like The Ladder, a pro-lesbian publication designed to “alert” readers to lesbian media in publishing that ran from 1956 to 1972, just one example of the rising lesbian conscious called into being in part by this heightened visibility (Foote 175). Even when the Supreme Court’s weakening of obscenity laws depleted publishing interest in soft-core pulp pornography in favor of explicit pornographic magazines and film in 1965, ending the genre completely, these communities lived on and played significant roles in gay liberation in the Stonewall Era (Keller 392).

Thus, scholars debate whether the pulps through their homophobic and forcibly tragic endings and hypersexualization were an interesting if problematic phenomenon in the history of LGBTQ+ communities, or whether their ability to bring lesbianism to the American mainstream and connect disparate lesbians to a greater identity qualified them as worthy cultural heritage. I would argue that Gold Medal Books played an important role in lesbian liberation not because of what straight editors or the plethora of male writers added to the American bookshelf, but because of what lesbian readers and writers made of the sudden available space in the American conscious. Gold Medal Books, in its desire to exploit lesbian desire for a profit, inadvertently created a space for lesbians to produce a lesbian narrative that, even when constrained by the homophobia of its time, presented opportunities for queer women to express and enjoy themselves. In other words, disdaining pulps as low-brow pornography ignores the fact that they were “participants in a field of symbolic struggle defined not only by market conditions but by the struggle of social actors to invest a given book with cultural value” (Foote 171).

Bannon, Meaker, and Torres’ pulps were formative because they willed into existence a network of connections that fostered a communal lesbian identity. In other words, the pulps’ value as lesbian heritage lies “not in the streets they depict,” which were problematic at best, “but in the notional avenues of circulation they now embody” (Foote 182). Lesbian pulp and Gold Medal Books mattered because lesbians and straights together were reading them. In experiencing homophobia through the eyes of likeable heroines terrified by heteronormativity and the risk their sexuality presented to them, the pulps presented a narrative to straight readers that was sympathetic to queer struggles, challenging the conventional tropes of queer violence and queer degeneracy while seemingly obeying them. Conversely, by creating a common experience for lesbians across the country and allowing readers separated and isolated by geography the opportunity to see themselves in literature, the pulps fostered a universal lesbian identity that otherwise would not have existed in the pre-Stonewall Era. In this way, the lesbian pulp genre “represents a tradition that precedes and anticipates lesbian readers,” where conflicted female readers chose a book that at once allows them to forget and remember themselves as lesbian women (Foote 172). Scholars remain polarized over whether “the McCarthy era is a kind of cul-de-sac off the road to liberation” for its problematic portrayals or whether it constitutes an “on-ramp” to Stonewall (Nealon 745). In reality, the pulp genre was a ladder that allowed women readers to claw themselves out of the darkness through a manhole that Gold Medal Books accidentally opened, and when the tides of editorial interest shifted in 1965 and that manhole closed, readers punched through the door violently and would not be denied.

Appendix

Lesbian pulps were books if not defined by their covers, then severely restricted by them. Emphasizing women’s knowing glances and states of undress, publishers designed covers that appealed to straight male voyeurism. In this appendix are a select few of covers that Gold Medal Books published.

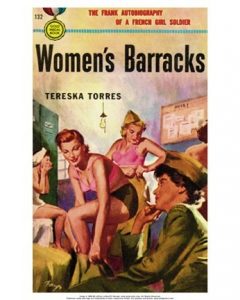

Women’s Barracks Original Cover (1951)

The first of Gold Medal Books’ lesbian pulps, Women’s Barracks started the trend of lesbian pulp covers’ salacious exploitation of the feminine form. On the book face, Ursula and the other women telegraph their lesbian desires through knowing glances while in states of undress while the book boasts a “frank autobiography.” An editor could market this blurb as merely the writer’s intent to carefully handle a sensitive subject, whereas the reader could reasonably assume that “frank” referred to the more explicit relations of the women in the text. Note the Gold Medal Book icon in the left-hand corner.

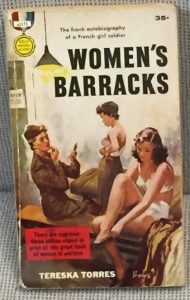

Women’s Barrack Second Edition (1951)

Responding to backlash from the Senate Committee on Pornographic Materials and conservatives across the country, the second edition of Women’s Barracks averted the eyes of the two leads and lessened the amount of undress the women on the cover.

Vin Packer’s Spring Fire (1952)

Leda and Mitch grace the cover of Spring Fire boasting matching pouts. Mitch, as the butch of the relationship, sports short hair and an assertive look; Leda, as the feminine and more reluctant partner, turns demurely to her left, sporting longer hair that marks her as the femme. Again, the cover boasts “frankly, honestly written” content, and the women’s state of undress signals lewd content.

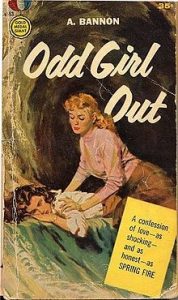

Ann Bannon’s Odd Girl Out (1957)

Bannon’s first novel Odd Girl Out features two women at odds even as they appear together. The aggressor leans over a seemingly unwilling woman, who stares blankly to communicate her passivity.

Ann Bannon’s I Am a Woman (1959)

Putting on full display a sultry pout and full cleavage, I Am a Woman emphasizes the lesbian content of the novel both textually with its brazen title that Bannon did not chose and its frustrated, rebelling cover subject.

Ann Bannon’s Women in the Shadows (1959)

Unlike I Am a Woman’s reliance on sexuality to telegraph its lesbian content, Women in the Shadows uses the public’s association of gay men and women with shadows, secrets, and dark spaces to attract readers looking for the pulps.

Works Cited

Abate, Michelle. “From Cold War Lesbian Pulp to Contemporary Young Adult Novels: Vin Packer’s Spring Fire, M.E. Kerr’s Deliver Us from Evie, and Marijane Meaker’s Fight against Fifties Homophobia.” Children’s Literature Association, 2007 . pg. 231-251.

Carter, Julian. “Gay Marriage and Pulp Fiction: Homonormativity, Disidentification, and Affect in Ann Bannon’s Lesbian Novels.” GLQ Duke University Press vol. 15, no. 4, 2009. Doi:10.1215/10642684-2009-003

Cuordileone, K. A. “”Politics in an Age of Anxiety”: Cold War Political Culture and the Crisis in American Masculinity, 1949-1960.” The Journal of American History, vol. 87, no. 2, 2000, pp. 515. ProQuest, https://login.proxy.lib.duke.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/docview/1518319148?accountid=10598.

Foote, Stephanie. “Pulps and the Making of Lesbian Print Culture.” Signs, vol. 31, no. 1, 2005. 169-190.

Johns, Merryn. “Pulp Pioneer: Ann Bannon reflects on writing lesbian fiction in the 1950s.” Curve, vol. 21, no. 2, 2011. pg. 72-73.

Keller, Yvonne (2005). Ab/normal Looking, Feminist Media Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, 2005. pg. 177-195. Doi:10/1080/14680770500112020

Miller, Meredith. Secret Agents and Public Victims: The Implied Lesbian Reader. Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 35, no. 1, 2001. ProQuest. Pg. 37.

Nealon, Christopher. “Invert-History: The Ambivalence of Lesbian Pulp Fiction.” New Literary History, vol. 31, no. 4 2000. pg. 745-764.

Passet, Joanne. Hidden in Plain Sight: Gay and Lesbian Books in Midwestern Public Libraries, 1900-1969. Library Trends, vol. 60 no. 4, 2012. pg. 749-764.

Radtke, Sarah and Maryanne Fisher. “An Examination of Evolutionary Themes in 1950s-1960s Lesbian Pulp Fiction.” Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology vol. 6, no. 4, 2012. pg. 453-468.

Server, Lee. Encyclopedia of Pulp Fiction Writers. New York: Facts on File. 2002.

Stryker, Susan (2001). Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback. Chronicle Books: Hong Kong.

“The reluctant queen of lesbian literature.” Independent [London, England]. 5 Feb. 2010, p 30. General OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A218227671/ITOF?u=duke_perkins&sid=ITOF&xid=11f83e17.