By Elaine Cox (2018)

Gay romance, which has often gone by the name Male/Male (M/M) due to its fan fiction origins (Brooks et. al), is a subgenre of romance consisting of stories focused on the romantic relationship between two men. While these stories have a wide range of sexual contact included, some people today expect gay romances to be more erotic than their heterosexual counterparts (Suede). This post will trace the history of erotic stories that preceded gay romance, and the eroticization of the gay subgenre since its inception.

Terminology

Before continuing, it’s necessary to define what erotica and similar terms mean in the context of mainstream romance fiction, or romance stories published by major publishing houses. Bestselling romance author Sylvia Day outlines the difference between many of these terms on her website.

According to Day, “Porn” is produced to induce orgasm in the consumer. “Erotica” refers to novels that focus on how character’s “sexual journey” influences their development as people. These novels do not necessarily have to develop a romantic relationship or provide characters with a Happy Ever After: two intrinsic parts of a romantic novel. The blog All About Romance corroborates this fact, explaining how erotic novels are sometimes incorrectly packaged as romance (Marble). An “erotic romance,” however, focuses on the development of a romantic relationship through sex, while “sexy romance” works contain explicit sex scenes, such as oral or penetrative sex, that aren’t inherent to the development of the relationship (Day). Ergo, sex doesn’t inherently make a piece of work erotic; it is erotic when the story itself is dependent on sex.

Censoring Queer Relationships

To understand the emergence and eroticization of gay romance in recent years, it is important to trace mainstream publishing’s portrayal of gay romantic relationships through the years. While the gay romance subgenre wasn’t introduced in mainstream publishing until 2009 (Whalen 4), gay relationships have been portrayed in published works since the 1950s and ‘60s. American censorship laws limited their portrayal in the decades prior (Bronski 679).

From 1873 (Rosenfield 28) up into the 1950s and ‘60s, the US government censored published materials for “obscene content” (Bronski 679) under the Comstock Act (Rosenfield 28). Vague terminology allowed for a wide range of “sexually explicit” materials to be banned, including scientific works on contraception and sexual education, as well as pornographic materials (Horowitz 30). It also included materials with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) content of any kind (Bronski 679). So while heterosexual sex on the page was banned, so were same-sex couples holding hands.

World War II brought big changes to the queer community. Draft boards began screening for homosexuals to expedite discharges for soldiers suspected of sodomy (Benes). The nature of questions asked during screenings made some men realize their sexual orientation (Stryker 11), and many enlisted had their first sexual experiences while serving (Benes). During WWII, soldiers dishonorably discharged for homosexuality were dumped into big port cities (Stryker 11). Scores of these discharged soldiers opted to stay in these locations. One writer for the popular magazine Rolling Stone suggests they did so to avoid social ostracization back home, leading to “large and visible gay communities [in places like] San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York” (Benes).

It was at this time that some queer characters in fiction began to become somewhat visible (Hugh 626), but mainstream romance was still years away from accepting gay romantic relationships.

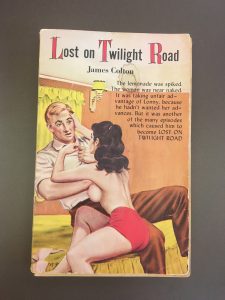

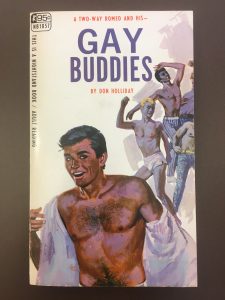

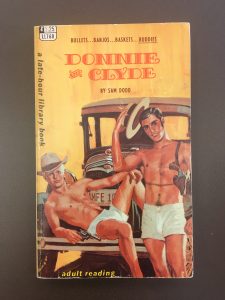

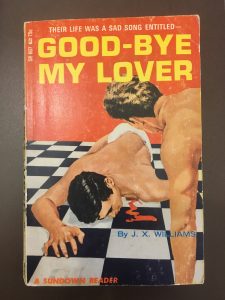

Queer Pulp Fiction To Queer Literary Fiction

The 1950s and ‘60s brought multiple U.S. Supreme Court rulings to change the longstanding censorship laws (“Gay American Pulps”). Following these legal victories, authors began producing a type of novels known as queer pulp fiction (“Gay American Pulps”). These cheaply produced novels depicted gay or lesbian relationships (Bronski 677). Laura Micham, Duke University librarian and archivist, who worked extensively with many of these books, explains that queer pulps were written in a 9 to 5 desk-job setting, with authors focused on quantity rather than quality. Publishers controlled everything about these books, from cover art to content, with authors unaware of changes made (Micham). The image below exemplifies how little the authors knew about their published works. It shows an email correspondence from an author of the queer pulp Goodbye My Lover admitting he never added an orgy scene, among others, to his work.

It’s important to note that I have not used “romance” to describe queer pulp fiction. As outlined by the Romance Writers of America, a romance novel is defined as a novel with “a central love story and an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending” (“About the Romance Genre”). Queer pulps often had central relationships, but the endings were anything but happy. The vast majority of these books had tragic endings for homosexual characters (Bibler 127), and any of these novels featuring ‘bisexual’ characters ended with them being in a heterosexual relationship or death (Stryker 32).

To the queer commuity, however, these novels offered their only representation for many years (Grimaldi). It was also a window for the general population to view gay relationships, and what they saw was highly erotic (Micham). While University of Missouri associate professor Elisa Glick notes that this “golden age” of queer pulps was mostly lesbian (Glick 124), University of Arizona professor Susan Stryker notes this era was one of bisexual themes rather than being explicitly gay (Stryker 45).

By the mid-sixties, these novels had become essentially “porn” (Stryker 45). There was little plot or development, and stood to only provide orgasm to the reader. This also coincided with a substantial increase in novels dealing explicitly with gay desire instead of lesbian (Stryker 107). These gay pulps were often more sexually explicit than their lesbian counterparts (Micham), demonstrating how gay male relationships were eroticzed before the gay romance subgenre was introduced.

The ‘70s and ‘80s brought the publication of queer literature, novels focused on the queer experience, outside of gay pulps. The Stonewall Book Awards recognizing “exceptional merit releating to the gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgender experience” gave its first award in 1971 (“Stonewall Book Awards”), and Lambda Literary Awards followed suit years later in 1989 (“A Brief History of Lambda Literary”). However, Lambda did not recognize any romance awards until 14 years later, in 2003 (Cerna), demonstrating the gap before LGBTQ romance fiction was recognized even within the LGBTQ literary sphere.

This era also brought the first happy endings for gay couples. E.M Forester’s (1879-1970) novel Maurice, posthumously published by Hodder Arnold in 1971, catapulted the gay romantic experience into the popular sphere (Brookes 45), only a year before The Flame and the Flower, published by Avon in 1972, opened the romance genre to explicit sex (Faircloth).

In fact, gay writers in the ‘70s struggled to depict their own relationships. If they spent too much time in their literary works on sex, they reinforced existing notions that homosexuals were obsessed with sex (Bergman 181). When they left homosexual sex unrepresented, they implied that it was shameful (Bergman 181). Newspapers focused on the gay sex instead of the literary content of gay fiction (Hugh 627), and the majority of gay fiction in the ‘70s still depicted men with lots of partners (Hugh 635).

The Emergence of Gay Romance

The 2000s brought the beginnings of gay and M/M romance. While these terms are often used

interchangably by people in the industry, best-selling gay romance author Damon Suede asserts they are distinctly different (Suede). Gay romances are the couterparts to heterosexual romance; offering just as much potential depth and development as traditional heterosexual romance (Suede). Suede suggests that M/M romances are the erotic, often underdeveloped romance stories that “come out of teenage fan fiction” (Suede). These slash fan fiction stories depict two same-sex fictional characters written into a romantic, and often sexual, relationship (Brooks et. al). Though erotic in content, the fictional M/M pairings consistantly got happy endings: a necessary requirement for the romance genre (Grimaldi).

Despite the differences between gay and M/M romance, the emergence of both subgenres bennefitted greatly from the rise of digital self-publishing in the early 2000s. Authors had more freedom to explore same-sex relationships without the restrictions of a publishing house (Whalen 9). Original gay romance pieces appeared (Whalen 7) as well as M/M fan fiction. Digital self-publishing also allowed for easy access to readers, allowing for an audience without distributors (Whalen 9).

Many of these self-published works found eager readers, leading mainstream publishers to pick up the genre (Whalen 6). The first was Running Press with two novels in 2009, and these books were notably soft-core erotica (Whalen 4-5). Soft-core simply indicates the sex acts in these books are more suggestive than explicit, and the sex itself is less aggressive. For example, soft-core penetrative sex may describe the foreplay explicitly, but use suggestive terms to describe the lovemaking, whereas hard-core would describe the entire encounter explicitly. As the dependence of a character’s development on their sexual journey defines erotica, the presentation of the sex matters less than how it impacts the development. Thus, the romance industry saw even the first mainstream gay romances as relying on sex enough to merit an erotica label.

Erotic romances were becoming commonplace themselves at the time of gay romance’s emergence. Ellora’s Cave, a notable erotic romance publisher, began in 2000 (Roach 80). This publisher had a gay and lesbian line of erotic romances, “Spectrum” (Reid), and the first books in this line began in 2005 (“Ellora’s Cave: Spectrum”). Thus, an erotic romance publisher was quicker to embrace gay romance than mainstream publishers.

Erotic romance entered the mainstream with Fifty Shades of Grey by Vintage Books in 2011 (Roach 81). The commercial success of Fifty Shades caused erotic romance and erotic novels to see a spike in sales (Costanza), and publishers took notice (Rosman). The success of the Fifty Shades series encouraged sales even years later: erotic romances saw a steady, double-digit increase in sales growth from 2014 to at least 2016 (“A Profitable Affair”).

The sudden mainstream success of erotic romance happened just two years after gay romance made its mainstream debut in 2009. So almost immediately after its appearance, gay romance had the ability to be explicitly erotic

The Eroticism and Erotic Content of the Gay Subgenre

In 2017, author and blogger Hans M Hirschi looked at Amazon’s romance offerings. From the numbers he presents, nearly one third of romantic novels offered are categorized as erotica, approximately 32% (Hirschi). Yet nearly half within the lesbian/gay literature and fiction subcategory are categorized as erotica (Hirschi). Thus, lesbian/gay literature has 18% more of its offerings subcategorized as erotica than general romance.

Until 2013, there wasn’t even a gay & lesbian category on Amazon. In an interview, Damon Suede recounts the categorization before his intervention:

“Amazon ranked all gay romance… as erotica. …And I was furious about it… I went and found a woman named Jessica Poore… and she said I’ll have it fixed by tomorrow… Until that moment, there were literally [gay] YA novels with no intimate contact at all, not even hands brushing, categorized as erotica” (Suede).

Even just a few years ago, the genre was eroticized more than heterosexual romances. So though Suede began our chat by noting that heat levels, a scale ranging from sweet to spicy to indicate how explicit a text is, for gay romances were “all of the above” (Suede), he was quick to note how this subgenre is primarily eroticized because of the same-sex relationships. He says people today “absolutely” expect M/M romance to be more erotic than heterosexual romances (Suede).

These attitudes aren’t limited to romances, however. Many non-LGBTQ people view LGBTQ relationships as “hypersexual” (Bolling). The definition of hypersexual is “dysfunctional preoccupation with sexual fantasy, often in combination with the obsessive pursuit of casual or non-intimate sex; pornography; [or] compulsive masturbation” (Weiss). Thus, some non-LGBTQ persons believe LGBTQ persons to want sex to the point of deviancy.

Suede expands on the eroticization of the genre admitting, “taboo sells,” and citing a specific period that contributed to people’s perceptions of gay romance:

“[2013 to 2016 was this time] when people were like ‘Yeah, yeah, I’m going to write a gay romance and there’s going to be fisting- and urine- and bestiality’ all this stuff. It wasn’t a LGBTQ romance- they were just breaking down taboo…. I do think that because of that… of how LGBTQ people are portrayed [as sexual] in mass culture and the fact that this stuff sells, there’s a persistent perception in the romance community that it’s dirty, it’s inherently dirty” (Suede).

Despite gay romances offering a variety of heat levels, a subset of gay erotic romance novels have shaped some people’s perceptions, causing them to view the subgenre as “inherently” erotic.

Speaking to the actual erotic content of gay romance, sex attitude research shows that only 4/10 gay men will have anal sex, and yet a substantial number of gay romances feature this act (Hirschi). Another article notes how the subgenre often disrespects gay male relationships and sex (Brownworth), noting how terminology is used incorrectly, and how gay romances often fetishize homosexual relationships (Brownworth). According to these critics, the content of gay romances isn’t always reflective of real homosexual relationships.

Conclusion

Gay romance as a mainstream subgenre has only existed for around a decade, but the portrayal of gay romantic relationships existed prior. US government censorship of materials with LGBTQ content through the Comstock Act prevented portrayals of gay relationships for decades until the 1950s and ‘60s. Queer pulp fiction then portrayed the first gay relationships in mainstream media, most often as hyper-sexualized stereotypes of gay male relationships. The gay fiction of the ‘70s and ‘80s marked the beginning of queer literary fiction, but still often portrayed gay characters as sexually promiscuous.

With the rise of slash fiction and digital self-publishing in the 2000s, the mainstream emergence of M/M and gay romance finally occurred. These romances have a range of heat levels, yet some readers still view them as inherently erotic, and the depictions of homosexual relationships have been critiqued for inaccuracy. Even with mainstream publishing’s acceptance of the gay romance subgenre, the “erotic” brand still clings to it.

Bibliography

“About the Romance Genre.” Romance Writers of America. Accessed 22 Feb 2018. https://www.rwa.org/p/cm/ld/fid=578.

Benes, Ross. “How Exclusion From the Military Strengthened Gay Identity in America.” Rolling Stone. 3 Oct 2016. Accessed 1 Apr 2018. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/how-exclusion-from-the-military-strengthened-gay-identity-in-america-w441663.

Bergman, David. The Violet Hour: The Violet Quill and the Making of Gay Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Bibler, Michael P. “The Cold War Closet” in The Cambridge Companion to American Gay and Lesbian Literature, edited by Scott Herring. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Bolling, Jessa Reid. “LGBTQ community struggles with institutional, societal sexual stereotypes.” The Crimson White. 22 Feb 2018. Accessed 5 Mar 2018. http://www.cw.ua.edu/article/2018/02/n-lgbtq-community-sexual-stereotypes.

“A Brief History of Lambda Literary.” Lambda Literary. Accessed 3 Mar 2018.

https://www.lambdaliterary.org/lambda-literary-foundation/llf-history/.

Bronski, Michael. “Gay Male and Lesbian Pulp Fiction and Mass Culture” in The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature, edited by E. L. McCallum and Mikko Tuhkanen. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Brookes, Les. Gay Male Fiction Since Stonewall: Ideology, Conflict, and Aesthetics. New York: Routledge, 2009. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2015.1092910.

Brooks, Emily, Alex Buben, and Fender Lauture. “M/M Romance.” Unsuitable. Accessed 22 Feb 2018. https://sites.duke.edu/unsuitable/malemale-romance/.

Brownworth, Victoria. “The Fetishizing of Queer Sexuality. A Response.” Lambda Literary. 19 Aug 2010. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. https://www.lambdaliterary.org/features/oped/08/19/the-fetishizing-of-queer-sexuality-a-response/.

Cerna, Antonio Gonzalez. “15th Annual Lambda Literary Awards.” Lambda Literary. 9 Jul 2003. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. http://www.lambdaliterary.org/winners-finalists/07/09/lambda-literary-awards-2002/.

Costanza, Justine Ashley. “Ellora’s Cave CEO Talks ‘Fifty Shades of Gray’ And the Rise Of Erotic Romance.” International Business Times. 20 Aug 2012. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. http://www.ibtimes.com/elloras-cave-ceo-talks-fifty-shades-grey-and-rise-erotic-romance-751033.

Day, Sylvia “What is Erotic Romance.” Sylvia Day. 2005. Accessed 1 Apr 2018. http://www.sylviaday.com/extras/erotic-romance/.

“Ellora’s Cave: Spectrum.” FictionDB. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. https://www.fictiondb.com/series/elloras-cave-spectrum~20740.htm. c

Faircloth, Kelly. “The Sweet, Savage Sexual Revolution That Set the Romance Novel Free.” Jezebel. 12 Jun 2015. Accessed 1 Mar 2018 https://pictorial.jezebel.com/the-sweet-savage-sexual-revolution-that-set-the-romanc-1789687801.

“Gay American Pulps and Gay Male Mysteries & Police Stories.” Duke University Libraries. 10 Oct 2017. Accessed 1 Apr 2018. https://guides.library.duke.edu/queerpulps/gaypulps.

Glick, Elisa. Materializing Queer Desire: Oscar Wilde to Andy Warhol. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009.

Grimaldi, Christine. “Reader, He Married Him: LGBTQ Romance’s Search for Happily-Ever-After.” Slate: Outward. 8 Oct 2018, accessed 22 Feb 2018. http://www.slate.com/blogs/outward/2015/10/08/lgbtq_romance_how_the_genre_is_expanding_happily_ever_afters_to_all_queer.html.

Hirschi, Hans M. “Do gay male authors look down on M/M romance and their readers? #mmromance #LGBT # amwriting #amreading.” Hans M Hirschi. 12 May 2017. Accessed 5 Mar 2018. http://www.hirschi.se/blog/mm-romance-v-gay-fiction/.

Horowitz, Helen. Attitudes toward Sex in Antebellum America: A Brief History with Documents. New York: PALGRAVE MACMILLAN, 2006.

Hugh, Stevens. “Contemporary Gay and Lesbian Fiction in English” in The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature, edited by E. L. McCallum and Mikko Tuhkanen. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014

Marble, Anne. “Not Everything Erotic is Romantic.” All About Romance. 8 Jan 2009. Accessed 19 Apr 2018.

Micham, Laura, interview by Elaine Cox, 16 Feb 2018.

“A Profitable Affair: Opportunities for Publishers in the Romance Book Market.” Nielsen. 7 May 2016. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2016/a-profitable-affair-opportunities-for-publishers-in-the-romance-book-market.html.

Reid, Calvin. “Patty Marks: Sex, Romance, and Erotic Bestsellers.” Publishers Weekly. 24 Mar 2013. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/57460-patty-marks-sex-romance-and-erotic-bestsellers.html.

Roach, Catherine M. Happily Ever After: The Romance Story in Popular Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016.

Rosman, Katherine. “Books Women Read When No One Can See the Cover.” The Wall Street Journal. 14 Mar 2012. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304450004577279622389208292/

Rosenfield, Michael. The Age of Independence: Interracial Unions, Same-sex Unions, and the Changing American Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Stryker, Susan. Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback. Hong Kong: Chronicle Books, 2001.

“Stonewall Book Awards.” GLBTRT: A Round Table of the American Library Association. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. http://www.ala.org/rt/glbtrt/award/stonewall.

Suede, Damon, interview by Elaine Cox, 24 Mar 2018.

Weiss, Robert. “Hypersexuality: Symptoms of Sexual Addiction.” PsychCentral. Accessed 1 Apr 2018. https://psychcentral.com/lib/hypersexuality-symptoms-of-sexual-addiction/.

Whalen, Kacey. “A consumption of gay men: navigating the shifting boundaries of m/m romantic readership.” College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 228. Accessed 3 Mar 2018. http://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/228.