Toxic Masculinity in Anna Todd’s After Series

By Elizabeth Loschiavo (2019)

Introduction

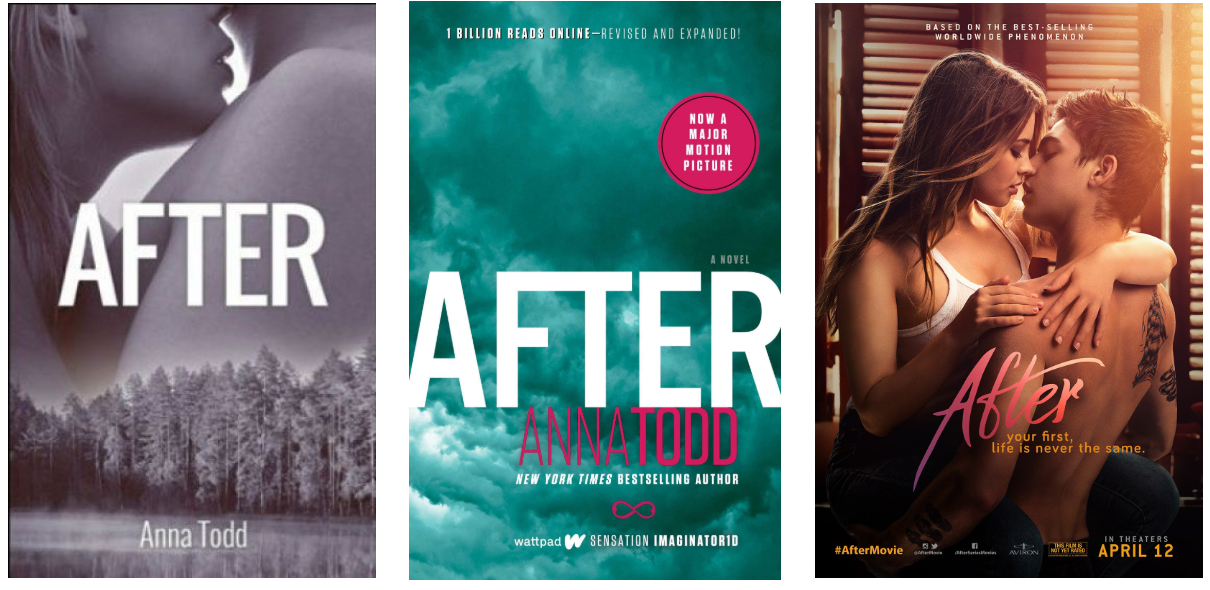

Anna Todd’s After series is the most recent example of a growing phenomenon in the publishing industry: converting online stories into print bestsellers. First published on Wattpad (a free online reading site that allows amateur authors to self-publish their works chapter-by-chapter) as One Direction fanfiction in 2013, the story has become an utter sensation, garnering over 1.5 billion reads on Wattpad and selling over 10 million print copies worldwide (Simon & Schuster 2019a). A film adaption premiered just last week on April 12. While After’s success suggests the online to print phenomenon is a positive force in the publishing industry, it also demonstrates the opposite by promoting unhealthy conceptions of masculinity. In this essay, I will first discuss After’s story – how it came to be the success it is today – in order to contextualize my analysis. I will then compare After to E.L. James’s hit novel, Fifty Shades of Grey, which underwent a similar virtual to print transformation, and reveal how both series feature dangerous notions of gender and relationships.

From Wattpad to Print

Before Anna Todd authored After, she was an avid reader of fanfiction herself (Todd 2013). She enjoyed reading “imagines” – micro-fan fiction in which the reader is the heroine “imagining” her life with the famous hero – written in the Instagram captions of popular One Direction fan accounts until she moved to Wattpad in 2012 after observing many of those Instagram authors make the switch (Malone Kircher 2015). For a while Todd remained only a reader, spending several hours a day reading fictional stories about one of her favorite bands (Alter 2014). One day in 2013, however, frustrated that none of her favorite authors had posted new material, she decided to try her own hand at writing (Bosker 2018). She tapped out the first chapter of After on her phone and posted it to Wattpad on April 11, 2013 (Todd 2013). A steamy, tumultuous tale of love between womanizing bad boy and One Direction member Harry Styles and virginal, innocent Tessa Young, After was inspired by the flurry of One Direction “punk edits,” which were Photoshopped images of band members with brightly-colored hair, tattoos, and multiple piercings, being circulated at the time (Kois 2015).

Regardless of which aspect of After – its sexiness, its famous hero, its “opposites attract” dynamic, or some combination thereof – appealed most to readers, her readership soon skyrocketed. In mere months, it had garnered over a million reads and thousands of comments which, though not uncommon for current Wattpad fanfictions, was extremely unusual at the time. After’s “blockbuster” status drew the attention of Wattpad employees who in the fall of 2013 reached out to Todd offering to represent her in selling the story’s rights, and soon she visited New York publishing houses with them acting as her agent (Bosker 2018; Kois 2015; Odell 2014). In May 2014, she signed a mid-six-figure, four-book deal with Gallery Books, an imprint of publishing giant Simon & Schuster (S&S) that included world and audio rights and, interestingly, left After freely available to read on Wattpad (though S&S did not publicize why they agreed to do so). In the same month, Todd also secured a deal with United Talent Agency that allowed them to represent film and television rights for the novel – rights which were then acquired five months later by Paramount Pictures (Reid 2014).

After’s massive following was what initially grabbed S&S’s attention. The publishers were excited by the prospect of the novel’s “built-in [online] audience” – Todd’s dedicated Wattpad fanbase – cultivated in part by her exchanges with them (Contrera 2014). When Todd began writing After and its sequels, After 2 and After 3, she did not proofread, outline, or plan anything. Rather, she gained inspiration real-time, drawing on readers’ comments and predictions about the previous chapters to shape the next ones (Bosker 2018). As the novel flourished online and Todd became something of a microcelebrity, such exchanges facilitated a rapport with her fans, dubbed “Afternators” (Kois 2015). Not only could Todd draw inspiration from her readers’ declarations of love for a certain scene or their expressions of frustration over the actions of a particular character, but she could also respond to them. These authentic fan-author interactions attracted S&S to her work and became a key factor in the transformation of her story to print.

S&S was also interested in After’s compelling storyline. According to S&S’s Adam Wilson, Todd’s current agent, the series’ highly addictive plot and numerous cliffhangers increased its marketability (Odell 2014). S&S believed these qualities would encourage readers to binge read, consuming After and its sequels in rapid succession. This expectation is reflected in the speed with which they published the entire series. In October 2014, Gallery Books released its first print run of After—80,000 copies, an unusually large amount.[1] Just one month later came After’s first sequel, renamed After We Collided, and its second and third sequels, renamed After We Fell and After Ever Happy, arrived in December 2014 and February 2015, respectively (Simon & Schuster 2019a). Commenting on the series’ quick publishing cycle, Wilson stated in 2014 that S&S had “learned to publish quickly when it comes to self-published authors,” alluding to the publishing house’s understanding of the importance of binge-ability for self-published works as well as its desire to capitalize on that aspect (Reid 2014).

Regarding After’s transition from Wattpad to print specifically, editors cut the extensive novel down to a hefty 592 pages, fixed grammar and spelling mistakes, excised side characters, added more sex scenes, and removed the fan-related aspects of the fiction, changing characters’ names (Harry Styles became Hardin Scott, for example) and even one of the hero’s tattoos to avoid copyright infringement (Ramdarshan Bold 2018, 117-136; Simon & Schuster 2019). S&S repeated this process with the other books in the series as well.

S&S also marked the book as “New Adult” romance and aimed for “college-age readers” because of the explicit sex scenes (Simon & Schuster 2019a), but Todd’s Twitter mentions show teens have “embraced the story” too (Kois 2015). Many of the users bestowing Todd praise are young women, which makes sense considering the fact that 40% of Wattpad’s demographic (and After’s original readership) is between 13 and 18 years old (Kois 2015).

This difference in intended and actual audience highlights an important aspect of S&S’s strategy: to increase After’s readership beyond its “built-in” one on Wattpad, from middle and high schoolers to college students. Though S&S targeted an older demographic, it also did not shy away from After’s origins. The series’ book covers identify Todd by her Wattpad nom de plume “Imaginator1D” and call her a “Wattpad Sensation” (Alter 2014).

The “New Fifty Shades”

Since its print publication, the After series has often been compared to E.L. James’ staggeringly popular Fifty Shades of Grey (Odell 2014). Both series have similar themes of emotional turmoil and trauma, and many parallels exist between the heroes, Christian and Hardin, and the heroines, Ana and Tessa. For example, both Christian and Hardin faced maltreatment as children and face recurrent nightmares because of it. Similarly, Ana and Tessa are both bookish college virgins pursuing careers in the publishing industry (Todd 2013). In fact, Todd was actually influenced by the Fifty Shades trilogy and has said that it “totally changed [her] reading life” (Odell 2014). Another comparison often drawn between the two series stems from their transformations from self-published fan fiction to print and film. Fifty Shades was first released in 2011 on Fanfiction.net (a self-publishing site similar to Wattpad but exclusively for fan-related works) as Twilight fan fiction (Thompson 2017). Much like After did, it soon “ballooned,” and then mainstream publishers and movie studios took note (Malone Kircher 2015). While their journeys differ in that After got its start on Wattpad, not Fanfiction.net, both Todd’s and James’s stories are similar in both content and trajectory.

The similarities between After and Fifty Shades also extend to their respective criticisms. Besides complaints of “bad and unrealistic” prose, both series have also faced severe backlash from feminists for their respective portrayals of Hardin and Christian (Faircloth 2014). Both leading men are overtly possessive, vindictive, and emotionally abusive. When Hardin and Christian perceive Tessa and Ana interacting with other males, even platonically, they become suspicious and domineering, interfering in the heroines’ healthy friendships. Moreover, Hardin and Christian are unable to express their feelings or insecurities, so they lash out at Tessa and Ana when something goes wrong, becoming spiteful and self-destructive. Finally, while neither Hardin nor Christian hit their partners in either series, their actions are clearly abusive. Every time they make a mistake they manipulate Tessa and Ana into forgiving them, gaslighting the women into questioning why they were upset in the first place or blaming their faults on their immense, uncontrollable love for the heroines.

These traits paint a grave picture of what healthy masculinity and relationships look like. While Hardin and Christian’s inability to effectively share their emotions are in line with the “strong, silent” type often portrayed in romance novels, this quality acts as a detriment to their own psyches and relationships. Not only does it prevent Hardin and Christian from dealing with their traumatic pasts, but it also facilitates their anger issues and vindictive tendencies. Furthermore, it prevents positive communication with Tessa and Ana, thus weakening the foundation of both relationships. Hardin and Christian’s jealousy is also extremely harmful. The two men treat Tessa and Ana as objects that belong solely to them—literally, in Christian’s case—with little regard to the heroines’ feelings on the matter. Ana might sign the contract to become Christian’s submissive and Tessa may cosign the lease to her and Hardin’s shared apartment, but those signatures in no way sign away their right to have friendships with Jose and Landon.

By revering Hardin as a hero and his relationship with Tessa as an epic love story, the series validates disrespectful behavior and paints Hardin’s volatility as a sign of his overwhelming love for the heroine. When considering the ages of those consuming After, the implications of this portrayal become all the more important. A young 13-year-old girl might not understand the difference between a healthy relationship and that which After details and mistakenly identify it for one. Now that the novel has been made a film, it becomes much easier for girls to internalize other problematic aspects of the story as well. In a recent post on The Mary Sue, an inclusive, feminist site for “geek girls,” one blogger called the film trailer “problematic” because it implied Hardin had “irrevocably changed” Tessa simply by being her first sexual partner (Gardner 2018). Though these sorts of objections are not new to the romance genre by any means, After’s fame and influence, especially among teens and young adults, makes it necessary to analyze the kinds of messages it conveys.

Conclusion

Though Anna Todd’s After series has garnered immense success across mediums—self-published online fanfiction, print novel, and now Hollywood feature—its transformation has not been wholly beneficial for the publishing industry or society at large. Like its twin, E.L. James’s Fifty Shades trilogy, After promotes harmful conceptions of “healthy” relationships and masculinity. Rather than display Hardin’s possessive and vindictive behavior for what it is—emotional abuse—the After series makes light of his rash tendencies. Not only does this portrayal mimic cliché representations of other heroes in the romance genre, but it also contributes to stunted notions of men’s emotionality. Most importantly, it irresponsibly conveys to young, primarily female audiences that they deserve a romance like “#Hessa’s”—one without mutual respect, consideration, or boundaries.

[1] While professionals disagree on what constitutes a “good” print run, Dana Isaacson, a former Senior Editor at Penguin Random House for thirteen years, denotes a 25,000-copy run of commercial trade paperbacks as the benchmark to meet (Isaacson 2018).

Bibliography

Alter, Alexandra. 2014. “Fantasizing on the Famous.” New York Times, October 21. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/22/business/media/harry-styles-of-one-direction-stars-in-anna-todds-novel.html.

Bosker, Bianca. 2018. “The One Direction Fan-Fiction Novel that Became a Literary Sensation.” The Atlantic, December.

Contrera, Jessica. 2014. “From ‘Fifty Shades’ to ‘After’: Why Publishers Want Fan Fiction to Go Mainstream.” The Washington Post, October 25. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1616306758.

Faircloth, Kelly. 2014. Book is Supposedly New 50 Shades, but is really just Sloppy Fanfic. Jezebel.

Gardner, Kate. “Can we Please make Movies Out of Better Fanfiction than After and Fifty Shades?” accessed March 7, 2019, https://www.themarysue.com/after-movie-fanfiction/.

Isaacson, Dana. “Numbers that Matter in Book Publishing.” Career Authors., last modified -02-26T09:55:58+00:00, accessed April 23, 2019, https://careerauthors.com/print-run-numbers/.

Kois, Dan. “How One Direction Superfan Anna Todd Went from Waffle House Waitress to Next-Big-Author with Erotic Fan-Fic Series ‘After’.” accessed March 7, 2019, https://www.billboard.com/articles/magazine/6634431/anna-todd-after-one-direction-fan-fiction-book-deal-movie-rights-profile.

Malone Kircher, Madison. “This Woman Wrote One Direction Fanfic on Her Phone and Ended Up with a Major Book Deal.” accessed March 7, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/anna-todd-earns-book-and-movie-deals-for-one-direction-fan-fiction-2015-7.

Odell, Amy. “This 25-Year-Old Turned Her One Direction Obsession into a Six-Figure Paycheck.” Cosmopolitan.

Ramdarshan Bold, Melanie. 2018. “The Return of the Social Author: Negotiating Authority and Influence on Wattpad.” Convergence 24 (2): 117-136. doi:10.1177/1354856516654459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516654459.

Reid, Calvin. 2014. “S&S Acquires Anna Todd’s ‘After’ Series from Wattpad.” Publishers Weekly Online, May 27.

Simon & Schuster. “After | Book by Anna Todd | Official Publisher Page | Simon & Schuster.” accessed March 7, 2019, https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/After/Anna-Todd/The-After-Series/9781476792484.

———. “Anna Todd | Official Publisher Page | Simon & Schuster.” accessed March 7, 2019, https://www.simonandschuster.com/authors/Anna-Todd/474410587.

Thompson Derek. 2017. “Fifty Shades of Grey, the Viral Myth, and the Truth about how Things Get Popular.” In Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction: Penguin Press. https://medium.com/@penguinpress/ever-wonder-how-fifty-shades-of-grey-became-such-a-phenomenon-6aab6657b819.

Todd, Anna. “After – Anna Todd – Wattpad.” accessed March 7, 2019, https://www.wattpad.com/story/5095707-after.