The Fashionable Approach: Glamorous Romances’ Relationship with Vogue Magazine in the 1950s

By Dylan Tuchman (2023)

Introduction

Glamorous Romances was a line of romance comic books created by Ace Magazines in 1949 and published until 1956, when the publisher ceased operations (Grand Comics Database). Before its demise, the company attempted to remedy its financial problems by marketing itself as a fashion-focused brand through its cover art (Nolan 2015, p. 86). In this paper, I will discuss how women’s fashion in the comic’s stories was similar to the trends displayed by Vogue magazine at the time. Furthermore, I will argue that the depictions of clothing and accessories worn by the female and male protagonists in Glamorous Romances mimic the trend patterns featured in Vogue, suggesting a possible inspiration by the illustrators. I begin by discussing the origins of Glamorous Romances and how fashion influenced their brand. I then transition into discussing women of the 1950s and the impact of Vogue. Next, I discuss three editions of Glamorous Romances — no. 56 (Dec. 1951), no.63 (Aug. 1952), and no. 75 (June 1954) — and compare them to Vogue editions published prior to the comic’s release dates.

About Glamorous Romances

From the late 1940s to the early 1970s, romance comics were a staple item for women of all ages (Nolan 2015, p. 12). As the craze roared, many companies transitioned to producing more comics in the romance genre. However, Ace Magazines was the only publisher at the time to discontinue other genres of pulps to focus more on romance titles (Nolan 2015, p. 62). By 1949, Ace had introduced nine titles, and Glamorous Romances was one of the first three released (Nolan 2015, p. 62). Although initially successful, Ace began to struggle as readers saw the art as repetitive and the stories as predictable (Nolan 2015, p .182). Each protagonist and her suitor looked the same across editions, making the stories less endearing as the love stories grew stale. In 1954, the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) created the Comics Code Authority to regulate and censor content in comic books. The CMAA enforced strict rules for what could be said in comics and promoted values about the nuclear family (Nolan 2015, p .12). Only nine publishers, including Ace, survived the post-Code period (Nolan 2015, p. 172).

Although Ace was originally a second-tier comic book publisher, it catapulted itself upward with romance titles. However, the new rules set forth by CMAA meant that Ace’s once relatable, promiscuous, middle-class protagonists could no longer tell their stories. While in 1951, Glamorous Romances featured protagonists who embodied the views of a typical American woman, by 1952, the comics shifted toward telling the story of the dream girl: the daughter every parent covets, the wife every husband desires. In 1954, the protagonist was no longer accessible to the reader: she was an idealized woman who was too close to perfect to be authentic. Ace’s success as a nine-title publisher plummeted soon after when six of its nine titles were canceled (Nolan 2015, p. 85). To keep itself afloat, Ace sought a new marketing strategy: cover art. Ace learned to distinguish its brand by appealing to the fashion sense of the young girls who searched for these comics. Their covers now featured pulp-style paintings of beautiful women with makeup and accessories (Nolan 2015, p. 86). Glamorous Romances learned to distinguish itself from other best-sellers by focusing on the day’s fashion trends.

1950s Women and Vogue

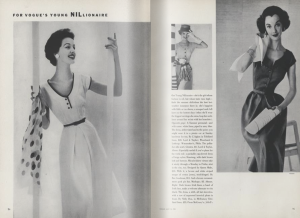

Many women in the 1950s sought out the beauty ideal prevalent in their culture (Englis et al. 1994, p. 50). Beauty was seen as a product of physical appearance and the services and activities required to achieve it (Nolan 2015, p. 86). Vogue magazine was a fashion titan, serving as a guide to achieving standard beauty (Crane 1999, p. 545). The magazine catered to all aspects of this ideal for white women, with sections on what dresses, shoes, coats, and makeup to wear, along with advertisements for cars, beauty products, travel, and overall good living. In the 1950s, Vogue documented a white upper-middle-class world (Crane 1999, p. 545). Many editions of the magazine included a section referencing “The Young NILlionaire:” a woman whose “fortune is nil, but whose taste runs high” (Vogue May 15 1952). The magazine attempted to provide a reader with fashion tips and advice to become the woman she always wanted to be. Photographs were taken in easily identifiable yet attractive settings, like fashionable cities or generic beaches. The camera was placed at eye level while the woman looked into the distance (Crane 1999, p. 545). Placing her eye-to-eye in locations that anyone could go to despite their financial situation created a recipe for an it-girl who was just the right amount out of reach (Crane 1999, p. 546). The tactic of having the model look away reveals an aspirational quality: she is simply enjoying her everyday life, and we, the viewer, are witnessing it up close. The women in Vogue in the 1950s still maintained a level of innocence that made them suitable, subservient wives. The magazine did not include nude legs, thighs, or breasts. Even though the clothing worn by the women in Vogue often suggested a sense of wealth, the actual photographic elements in the magazine allowed the average American to relate to the woman pictured.

1951

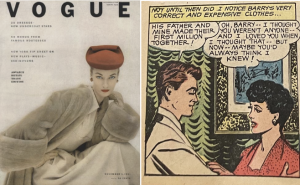

In 1951, the color was red. At least, it was, according to Vogue. Every cover of the magazine published in the year 1951 featured the color. If it was not seen in the model’s clothing, it was in her bold red lip. If it was not her bold red lip, it was the color of the text. Red swallowed the pages of the October 15 and November 1 editions: covers, models, featured art, and scrapbooks. Mrs. Exeter, a character created by Vogue who epitomized elegance and sophistication, had a column of her fashion ideas featuring a cinched waist, buttons, and a collar. She sported a form-fitting dress that could fit stylishly under a coat on a windy day. Perhaps a hat, a fur, and gloves could spice up the outfit further, with a nice pair of oversized earrings to further symbolize wealth when your hair was pinned (Vogue Nov 1 1951). Another page titled “From the August Paris Collections – Vogue Pattern Exclusive” featured the same looks as Mrs. Exeter’s: cinched waists, buttons, hats, and large earrings (Vogue October 15 1951). On the page “What to Wear to What,” a woman wore a large red cape with flowers of red and pink around her neck (Vogue November 1 1951). An article discussing carpets had the headline “New Scheme: Black, White, and Reds. New Red: Cotton Carpet” (Vogue October 15 1951).

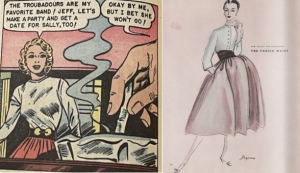

Glamorous Romances seemed to embrace red as the year’s color as well, with each of the protagonists in the December 1951 edition wearing it as their primary color. Rhonda Dale, the first woman we read about from “Everything but a Heart,” met her primary love interest in a red ruffled shirt, red leather pants, a bold red lip, and large red earrings. Upon meeting her second love interest, Rhonda was in a long red dress, cinched at the waist, with a small red jacket to cover her shoulders and a new pair of large red earrings. When Rhonda realized who her true love was, she was in a long red dress with a white collar (Nodel). The next protagonist was June Gersham from “I Played the Wrong Game.” June met her first love interest in a long red dress with buttons, a collar, and a black hat, and her second in a red off-the-shoulder dress cinched at the waist (Streeter). In “Grounds for Matrimony,” Eleanor met her love interest in a blue dress, which prompted him to say, “Why, she’s like something out of the funny papers! Her clothes must have been buried in an attic” (Giusto). However, when Eleanor changed into the same outfit as June, a long red dress cinched at the waist with a collar, her future husband realized he made a mistake. The woman was beautiful, after all. Although Adair Perry in “Eyes Only for Him” wore white as her primary color, her hair was red. As a nurse, all of her outfits had a red trim, making her hair color pop on the page (Streeter).

Rhonda, June, Eleanor, and Adair were not just beautiful: they had experiences similar to the average American middle-class woman in the 1950s. Rhonda said she had “a good job, but [she] spent every cent [she] made on beauty, clothes, and trips” (Nodel). Keeping Rhonda’s job vague made it easier for a reader to find her relatable, as women readers from different backgrounds could see themselves in her character if they found themselves spending more and more money on material goods. June was a recent high school graduate who took journalism and printing in school. She described herself as not being part of “the kind of people who could belong to a country club,” however she wanted to be (Streeter). June’s character appealed to a younger audience who just graduated high school and now searched for love. Eleanor was eighteen and experienced conflict with her mother (Giusto). She longed to be independent but ultimately fell into the arms of a loving husband. Adair was an orphan of seven years turned nurse who found love with the successful doctor who helped her through her darkest time (Streeter). The age gap between Eleanor and Adair showed how Glamorous Romances tried to find something for each reader to identify with. Nevertheless, each protagonist’s beauty became their getaway car to a new world, bringing a man to her like a magnet, who held the key to the life she always wanted. By the end of the story, she moved up the societal ladder and found her prince charming: and she just happened to be wearing red.

1952

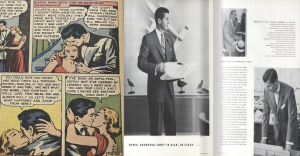

In 1952, red was certainly not displaced by Vogue but was given a sidekick: blue. The woman pictured on the cover of the June 1, 1952, edition was in a blue dress, cinched at the waist with a blue belt: however, she still featured the prominent red lip. May 15, 1952’s covergirl sported a red lip, red scarf, and dark blue romper, bringing out her blue eyes. Blue, the color of serenity, showed a movement toward spontaneity. A woman in blue is calm: she waited for a successful man to fall in her lap. The pop of red still symbolized the hunt for love: it may not be at the forefront of the woman’s mind, but she was always looking. The magazine featured a column entitled “Recommended for Week Ends: Shades of Blue” with suggestions for men’s clothing (Vogue June 1 1952). On the “Trial by Beauty” page, a woman applied a blue “liquid color” to her eyelids alongside a friend who applied a red one. In the magazine, blue was never featured without red (Vogue June 1 1952). Another article in the magazine included the section “News: Charcoal Gray in Silk, in Linen …” which featured different men in gray suits (Vogue June 1 1952). A page with different drawings showed the “New Policy for Separates: the Fascia Wait,” which was a thicker belt to bring your waist in even more (Vogue May 15 1952).

In August of 1952, Glamorous Romances’ first protagonist Lois Shelton wore a red dress with a blue cape and blue earrings. When they met, her male suitor wore a dark gray suit with a red bowtie. After the duo overcame their difficulties, the story ended with Lois in a long blue dress with a cinched waist and a collar and her love interest wearing a red coat over his gray suit (Streeter). In “Dangerous Encounters” Gayle Cartwright worked for her successful father, Jim. Gayle spent the duration of her story in a red collared coat with gold buttons over a long blue dress with a cinched waist courtesy of a blue belt. Her suitor wore a smooth gray overcoat and a blue tie (Rice). In “Round Trip to Romance,” Margie began her story in a green dress, dreaming of a better life for herself. Eventually, she met her male suitor in a light blue top with a fascia waist before a red skirt. Finally, she found her happy ending in a red dress with a white collar and buttons; her male suitor wore a dark gray overcoat (Walsh & Beck). “Second-Hand Glamour” featured Penny, who initially wore a long red collared dress with a hat and gold earrings before changing into the same outfit in blue when meeting her suitor. At the end of their story, Penny wore an elegant red dress with ruched straps, and her suitor wore a light gray jacket (Kirkpatrick).

Lois and Gayle had similar qualities but were born into privileged lifestyles. Lois was only sixteen when a famous advertiser noticed her, and she became a prominent model (Streeter). Gayle was a well-known actress from Long Island who was constantly around men that wanted a role in her program (Rice). Margie and Penny were more similar to the protagonists from 1951, whose beauty is overshadowed by circumstance. Margie had a wonderful singing voice, but her talent was silenced by her parents’ belief that singing was not a serious profession (Walsh & Beck). Penny was a gorgeous young woman from a low-income family who experienced a desire for beautiful and expensive clothes to the point that it “was almost an obsession” (Kirkpatrick). 1952 foreshadowed the beginning of Glamorous Romances’ movement toward protagonists who resembled a fantasy rather than a reality. While Margie and Penny are seen as more typical American girls, Lois and Gayle are the girls everyone dreams of being.

1954

1954 marked a shift away from color into universal aspects of beauty one could purchase: accessories, hairstyles, and makeup. In 1953, the women of Vogue became more unattainable: cover girls were no longer placed in front of blank white backgrounds (Vogue 1953). Instead, they were seen in exotic locations or placed next to other models, making it harder for the average woman to see herself in the women pictured. 1954 followed this trend, pushing the women of Vogue further from the grasp of middle-class Americans. While the blue-red color palette remained in place, readers also met green and pink. On the cover of the March 1, 1954, issue, both women featured a bold red lip in front of a light red background. One woman wore a pink dress with a green glove, a floral hat, and large earrings. The other wore a blue dress with a white glove, a sizeable, beaded bracelet, a floral hat, and earrings. The women were dressed almost identically, but the colors in their outfits differed. One woman stared directly at you, while the other looked at the woman next to her (Vogue March 1 1954). The viewer is meant to feel like an outsider: two women in matching outfits seemed to gossip about you as you looked on. Yet, the lack of a common covergirl, and a standard color palette, indicated a shift toward a new fashion trend: accessories. This idea was emphasized by the cover’s subheading, which stated, “American Fashion: Accessories in Action” (Vogue March 1 1954).

While the women seemed more exclusive, the products advertised were more attainable as they required more minor adjustments than changing the entire color palette of your wardrobe. The magazine told you to buy a new hat; buy this dress; buy this lip gloss (Vogue April 1 1954). The color red or blue was no longer the golden key to being desired. The April 1, 1954, edition further highlighted the shift away from prioritizing color in outfits. The cover featured a close-up shot of a woman with blue eyes, blue eyeshadow, and a bright red lip. Her outfit was not included; her accessories were not included; her hair was not even included. The focus of the cover was the woman’s makeup: makeup allowed a woman to accentuate the features she already had instead of starting from scratch. The leading fashion trends were floppy hats, stocking/t-shirt dresses, and updos. Prints were in; distinct colors were out (Vogue April 1 1954).

By the seventy-fifth edition of Glamorous Romances, published in June 1954, the publishing company expanded its color palette as well. In the earlier editions of the 1950s, close-ups of a woman’s face still included a glimpse of her outfit. Although it may have been the peaking of her collar or the top of her torso, her outfit was always visible. In 1954, close-ups began to exclude outfits, focusing on the woman’s face and expression. While the end panel for each protagonist still did feature the woman in red, the protagonist’s outfit choices throughout the story were much more variable. Marla, the first protagonist, began her story in a red dress but changed into a green bathing suit and a green patterned overcoat. Certain panels focused entirely on her accessories, excluding her face (Nodel & Rizzi). Carol Dean in “Guilty in His Eyes” wore a long green dress with long white gloves in her opening scenes. She eventually wore a maroon hat and a matching dress before ending her story in an elegant red gown (Hartley). Rosemary, the third woman, wore a green dress with a rose headband, neck scarf, and glasses (“My Sister Stood Between Us”). When she finally gave in to love, she was in a red hat, matching red dress, and blue earrings. Kay started in a red ball gown with puffy shoulders and a bonnet with red roses and ends it in the same outfit (Winter). Throughout her story, the reader can see images of her costumes, including a massive diamond ring, a glass slipper, rose earrings, and makeup products.

The four protagonists in this edition had privileged lives that few people could relate to. Marla was a famous young model who believed she was the company’s “best advertisement”; Carol was a prominent singer on her way to fame; Rosemary worked at a hospital alongside handsome doctors; Kay was a stand-in for a movie star in the play Cinderella. The difference in their professions showed that Glamorous Romances was still trying to relate to their readers but in a new way: the publishers wanted their fans to read the comics and see a glamorized version of themselves. By giving their protagonists professions associated with fame or spectacular achievement, Glamorous Romances allowed its readers to see their fantasies and dreams in the protagonists instead of seeing someone relatable to them. The comic books transitioned from a source that helped people make sense of their lives to one of escapism into an idealized version of your life.

Conclusion

Although it is unclear if the illustrators of Glamorous Romances were directly inspired by Vogue, there is an extraordinarily analogous relationship in the similarities between the fashion trends portrayed in the magazine and the comics. When Vogue deemed red the color, so did Glamorous Romances. When there were inklings that blue was becoming the color, Glamorous Romances was ready with their panel. When accessories became the focus, Glamorous Romances included a new kind of shot. Since Glamorous Romances was looking to distinguish itself and used the angle of fashion to do so, it is plausible that Ace used Vogue, the leading women’s fashion magazine, as an inspiration. When the protagonist received her “happily ever after,” she was in the day’s most fashionable clothing, promoting the idea that an idealized lifestyle was not only contingent on finding that prince charming but achieving the standard beauty ideal.

Bibliography

Crane, Diana. “Gender and Hegemony in Fashion Magazines: Women’s Interpretations of Fashion Photographs.” The Sociological Quarterly 40, no. 4 (1999): 541–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4121253.

Englis, Basil G., Michael R. Solomon, and Richard D. Ashmore. “Beauty Before the Eyes of Beholders: The Cultural Encoding of Beauty Types in Magazine Advertising and Music Television.” Journal of Advertising 23, no. 2 (1994): 49–64. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4188927.

Giusto, Frank. Glamorous Romances: “Grounds for Matrimony.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1951.

Glamorous Romances: “My Sister Stood Between Us.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1954.

Grand Comics Database. “Glamorous Romances.” Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.comics.org/series/11756/.

Hartley, Al. Glamorous Romances: “Guilty In His Eyes.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1954.

Kirkpatrick, Alice. Glamorous Romances: “Second-Hand Glamour.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1952.

Nodel, Norman. Glamorous Romances: “Everything but a Heart.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1951.

Nodel, Norman, and Mario Rizzi. Glamorous Romances: “Shamed Before Him.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1954.

Nolan, Michelle. Love on the Racks: A History of American Romance Comics. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2015.

Streeter, Lin. Glamorous Romances: “Eyes Only For Him.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1951.

Streeter, Lin. Glamorous Romances: “I Played the Wrong Game.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1951.

Streeter, Lin. Glamorous Romances: “Not Free to Love.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1952.

Rice, Kenneth. Glamorous Romances: “Dangerous Encounter.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1952.

Vogue. October 15 1951. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://archive.vogue.com/issue/19511001.

Vogue. November 1 1951. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://archive.vogue.com/issue/19511101.

Vogue. May 15 1952. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://archive.vogue.com/issue/19520515.

Vogue. June 1 1952. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://archive.vogue.com/issue/19520601.

Vogue. 1953. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://archive.vogue.com/issues/1953.

Vogue. March 1 1954. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://archive.vogue.com/issue/19540301.

Vogue. April 1 1954. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://archive.vogue.com/issue/19540401.

Walsh, Bill, and Dick Beck. Glamorous Romances: “Round Trip to Romance.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1952.

Winter, Chuck A. Glamorous Romances: “Don’t Break My Heart Again.” Springfield: Ace Magazines, 1954.