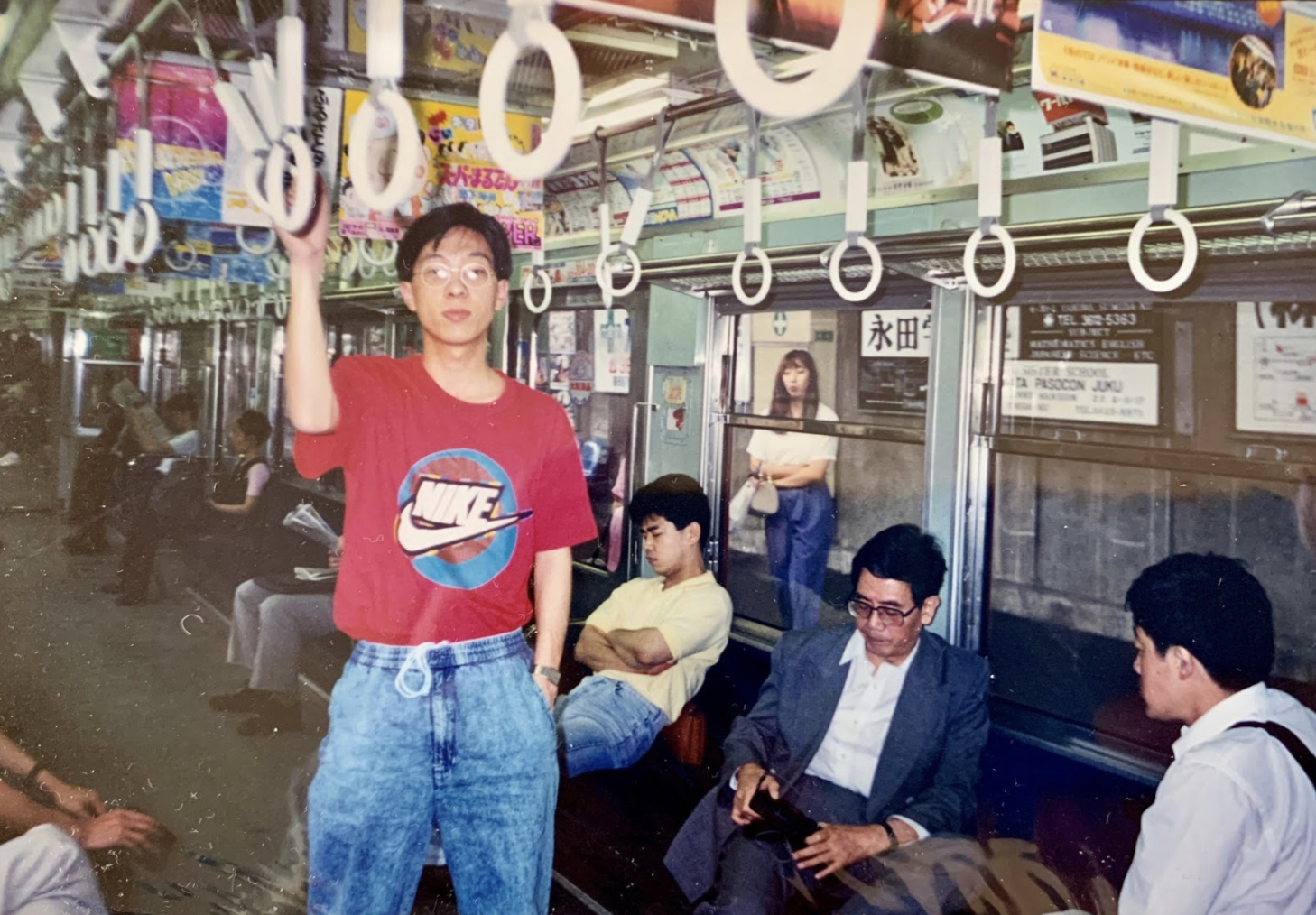

The year was 1990. Wang Lian had a date with Bao Liqiong.

He lived in downtown Shanghai; she lived in the suburbs. There was only one train connecting the two places and the last one left at 7 PM.

Unfortunately for him, it was already 7 PM when he leapt over the station gate. Alas, the passion of a man aged 23 years is outweighed only by his stupidity! Wang Lian ran alongside the moving train like a dog next to a speeding bike, eyes locked onto the nearest passenger car with its door still open. He jumps into the arms of the ticket collector, who stumbles back in shock and screams, “Do you fear no death?!”

This was not the last time Wang Lian pulled such a stunt. The second time he tried, however, an astute train conductor grabbed him by the waist and did not release Wang Lian from his bear-hug until the train had disappeared into the distance. The train conductor charged Wang Lian with a fine of 1 RMB. This was a rather dismaying situation for both parties, as Wang Lian had only a single hundred-RMB bill on him. The grumbling train conductor returned to the peeved Wang Lian no less than 99 RMB in cobbled change.

Bao Liqiong’s mother, Li Jun, adamantly disapproved of our young couple’s love. Li Jun liked men who were academic. Wang Lian was good with people. Li Jun liked men who were talented. Wang Lian was hard-working. Li Jun liked men who were handsome and strong. Wang Lian was charismatic and as lean as a bean sprout. In short, Wang Lian fulfilled none of her requirements for a son-in-law.

Without her mother’s approval, Liqiong felt like their relationship was a shameful secret, a clandestine operation to be kept in the shadows. By the time she was 23, Bao Liqiong was sick of the sneaky dates and parental pressure. She yearned to live life unrestricted.

The year was 1992. Liqiong’s younger sister, Yinhui, smuggled out a bag of clothes for her and urged her to chase her own happy bliss. The same night, our young couple bought a ticket to Beijing where Wang Lian’s grandfather lived. Liqiong didn’t tell a soul.

No one in her workplace was able to contact her. In a panicked frenzy, her parents reported to the police that she was missing. It was only after Yinhui called about her company’s threats to fire her did Liqiong finally return to Shanghai. She had been gone for a little over a week. After receiving a slap on the wrist, Liqiong was forgiven by her boss on account of her youth and the folly that naturally comes with it. As for her parents, they finally accepted our young couple’s relationship.

Wang Lian and Bao Liqiong eventually had a daughter who now regularly talks to her computer screen as she drafts monthly articles for The Wellian Magazine.

My mom will tell you that running away to Beijing was never really about my dad at all—it was about freedom. Her whole life until that point had been determined by somebody else. As a child, she had wanted to remain at the middle school she was already attending, but my grandmother didn’t let her; in high school, she had decided that she wanted to pursue a teaching career, but my grandmother didn’t let her; and now, she wanted to date my dad, but once again my grandmother didn’t let her.

Adding frustration onto repression was the fact that her home life was merely a microcosm of her larger society. Born in 1969, she grew up during the tail-end of Mao Zedong’s regime where personal liberties were still heavily curtailed. There was no freedom of thought: she was taught that any opinions deviating from those of authority figures were unequivocally wrong. And everything was assigned by the government: the district she lived in, the college she attended, the first company she worked for.

But my mom’s youth represented a generational turning point. After Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, China implemented a series of socioeconomic reforms that began opening up the cultural horizon to Western influence. For the first time, my mom was exposed to the possibility of living a life where she could think, say, and do anything she wanted. Suddenly, her life felt utterly inauthentic. What was the outside world really like? Questioning whether anything she knew was real at all, she resolved to find out for herself. She left China in 1997 for the same reasons she ran away to Beijing in 1992: to reclaim her agency.

Most of their friends actually advised my parents to stay in China. Financially, they were doing quite well. My dad worked as a night auditor at Shangri-La, a luxury hotel, and made 5000 RMB a month when the average wage was only 100. My mom worked as a businesswoman at an international trading company. They got married in 1992, and by their early 20s, they had already owned a house in downtown Shanghai worth 10 million RMB (or 1.5 million USD) today.

My family’s current net worth is only a fraction of what it could have been had my parents stayed in China. When my parents came to North America, they willingly gave it all up to pursue an ideal—not safety, not security, but freedom for freedom’s sake. I think that this alone is very telling of the privilege they had. Moreover, my paternal grandparents were already in the United States when my parents arrived. This meant that they immediately had a place to stay, even without income.

Their privilege does not erase the struggles they faced as immigrants. My parents had to re-do their undergraduate studies because their first Bachelor’s degree wasn’t good enough for American employers. They were ignored and ridiculed for being foreign, making the most mundane errands a difficult task. Reading the mail, communicating with teachers, and understanding the process for official applications all fell onto my shoulders ever since I was a third-grade kid. The language barrier was a constant source of shame—even now, my dad is embarrassed by his English despite having been fluent for decades. Starting over in a new country set my parents back by a generation.

Nonetheless, I think it’s critical to recognize that my parents had more than just the clothes on their back. They had connections that provided them with baseline security and expanded opportunities—an advantage that many Asian immigrants do not have.

The model minority myth heralds Asian Americans as the most economically successful racial group in the US because we have the highest median income. But this median is misleading, as it completely conceals the fact that income inequality among Asian Americans is also greater than that of any other race in the US. For example, American Progress reports that Taiwainese women make a median of $70,000 per year, whereas Vietnamese women make only $36,500. The startling socioeconomic disparity is reflected in levels of education, too. Data from 2015 shows that 71% of all Asians aged 25 and older have obtained a degree greater than a high school diploma, but only 42% of Laotians have done the same.

The recent shooting in Atlanta testifies to the difference in class privilege among Asian Americans: Sueling Wang, the chief executive of the company that operates Gold Spa, owns two properties worth a million each while Suncha Kim and Yong Ae Yue, two of the eight who died, worked multiple jobs to support their families.

The disparity exists on a much finer level as well. Suncha Kim and Yong Ae Yue worked multiple jobs, but my mother has never worked more than five days a week. When the Toronto Transit Commission hired my father as a bus driver, his income alone was enough to afford a comfortable life; so my mother quit her job to become a stay-at-home mom, and I grew up having her next to me for every waking (and sleeping) moment. Randy Park, whose mother Hyun Jung Grant spent days and nights working brutally long hours, didn’t have that same luxury. It would be wrong of me to say that my family’s experience is anywhere near comparable to theirs.

The shooter, a self-proclaimed addict who visited massage parlors for sex, told police that he was trying to eliminate sexual temptation. Within the surrounding discourse, the Atlanta victims have therefore come to broadly represent Asian-American sex workers. The collective grief and trauma caused by this event makes it easy people like me to self-identify with this group, especially since we are acutely aware of the reality that we all look the same to the average American.

But the difference is that we, as Duke students, are guaranteed a piece of paper worth $76,300 in annual median income a mere two years after graduation. In all likelihood, we won’t be stuck working a minimum-wage job. We won’t be forced into commercial sexual exploitation. Upon deeper reflection, it should become clear that we probably won’t ever find ourselves in a situation similar to theirs. Class privilege, to a certain extent, protects us from the worst.

This is why I cringe when Duke students point to the Atlanta victims and say without context, “It could have been me.” Of course, some Duke students do genuinely relate. Their voices are the ones that should be amplified. But given my background, any suggestion that it could have been me would only reinforce the harmful assumption that Asian Americans are a monolith. I would be undermining the gravity of another community’s circumstances and co-opting their narrative. At best, I would be naive; at worst, I would be oppressive. It is critical that I recognize what the overwhelming diversity within the Asian American community implies: there are aspects of our “collective trauma” that I don’t actually share.

Still, I am subject to the same bigotry and violence that led to the Atlanta shooting precisely because I am an Asian American woman.

The racialization of Asians in America inextricably merges race, class, and gender into one identity. This is not mere conjecture—this is a policy-driven phenomenon. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 is well known; what’s less known is the fact that the law barred the entry of Chinese laborers only. Merchants, students, teachers, and other specified groups of upper-class men were exempt from the ban so that the US could maintain its lucrative trade relationship with China. Furthermore, the act made no mention of women. It was commonly believed that all Chinese women were destined to become prostitutes, so lawmakers assumed that they killed two birds with one stone when they banned prostitutes from entering the US in 1875.

Now here’s the problem: how were immigration agents supposed to differentiate between Chinese laborers and non-laborers? The first piece of evidence was the section 6 certificate. These documents, issued by the Chinese government, indicated that a particular individual belonged to an exempt class. However, it quickly became the norm for immigration agents to suspect that Chinese “aliens” carried fraudulent documentation.

Immigration agents then turned to physical traits as markers of class. They were obsessed with detailing extensive descriptions of Chinese bodies in order to determine whether an individual was a laborer or not. Scars, marks, and calluses were all valid reasons for a Chinese man to be refused entry. The instructions received by the agents for these inspections were so meticulous that they spanned four single-spaced pages. Yet, their superiors often complained that the descriptions were too vague to be useful, as “[Chinese laborers] look much alike.” In 1891, US Congress even suggested that photographs were pointless because “a photograph of a Chinaman is something uncertain; even with both before you, that is, the photograph and the Chinaman, you sometimes find it very hard to tell whether a certain photograph belongs to a certain Chinaman or not.”

Given these difficulties, the ultimate instruction they received from Washington was starkly similar to the prevailing attitude about the determination of race. Government officials advised simply, “You’ll know it when you see it.”

I suppose the Atlanta shooter thought he “knew it when he saw it.” Ironically, it turns out that none of his victims were actually sex workers. He just assumed they were. This is the virulent legacy of anti-Asian policy from over a century ago that has festered in the American imagination ever since its inception.

The American conception of race was designed for class privilege to moderate the oppression of Asian Americans. Thus, identifying nuances in the Asian-American experience is equally important as recognizing similarities. Understanding the enforcement of not only anti-Asian racism but all racism in America is the preliminary step to destroying it.

I write this in hopeful mourning.

Bibliography:

- Bleiweis, Robin. “The Economic Status of Asian American and Pacific Islander Women.” Center for American Progress, 4 Mar. 2021, www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2021/03/04/496703/economic-status-asian-american-pacific-islander-women/.

- Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas, et al. “8 Dead in Atlanta Spa Shootings, With Fears of Anti-Asian Bias.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 26 Mar. 2021, www.nytimes.com/live/2021/03/17/us/shooting-atlanta-acworth.

- Calavita, Kitty. “The Paradoxes of Race, Class, Identity, and ‘Passing’: Enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Acts, 1882-1910.” Law & Social Inquiry, vol. 25, no. 1, 2000, pp. 1–40. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/829016. Accessed 12 Apr. 2021.

- Ellefson, Lindsey, and Rosemary Rossi. “There’s No Evidence Atlanta Spa Victims Were Sex Workers – So Why Is That Part of the Narrative?” TheWrap, TheWrap, 23 Mar. 2021, www.thewrap.com/atlanta-spa-victims-sex-workers-stereotypes/.

- Gao, George. “In China, 1980 Marked a Generational Turning Point.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 27 July 2020, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/11/12/in-china-1980-marked-a-generational-turning-point/.

- History.com Staff. “Chinese Exclusion Act.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 24 Aug. 2018, www.history.com/topics/immigration/chinese-exclusion-act-1882.

- Knoll, Corina, et al. “2 Immigrant Paths: One Led to Wealth, the Other Ended in Death in Atlanta.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 24 Mar. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/us/atlanta-shooting-spa-owners.html.

- Kochhar, Rakesh, and Anthony Cilluffo. “Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians.” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 21 Aug. 2020, www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/.

- “Laotians: Data on Asian Americans.” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 6 Apr. 2021, www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/asian-americans-laotians-in-the-u-s/.

- “Value of a Duke University Degree.” Niche, www.niche.com/colleges/duke-university/after-college/.