Let me ask: How are you feeling today?

“My chemicals are out of wack.”

“My last two brain cells are dying.”

“I am literally, seriously, clinically depressed.”

Among the culture of younger Americans, the language of the brain (of neuroscience) has permeated common parlance. Awareness of mental health disorders and acceptance of psychiatric methods has strengthened the powers of Psychology and Neuroscience as disciplines, epistemologies, and ways of life. At the same time, their concepts have become bloated and swollen, entering daily language in a way never imagined by the academic-scientific-medical communities that generated them. Clinical diagnoses became household references to habits or attitudes (“My OCD is acting up”; “Am I having a stroke?”; “What a psycho!”) and models of humanity based on the biological brain have proliferated. Am I really a human or am I simply the product of neurotransmitters passing through different membranes? Am I facing a spiritual crisis or are my chemicals simply imbalanced? These models challenge our “traditional” view of ourselves—the human as a mind or soul separate from the body.

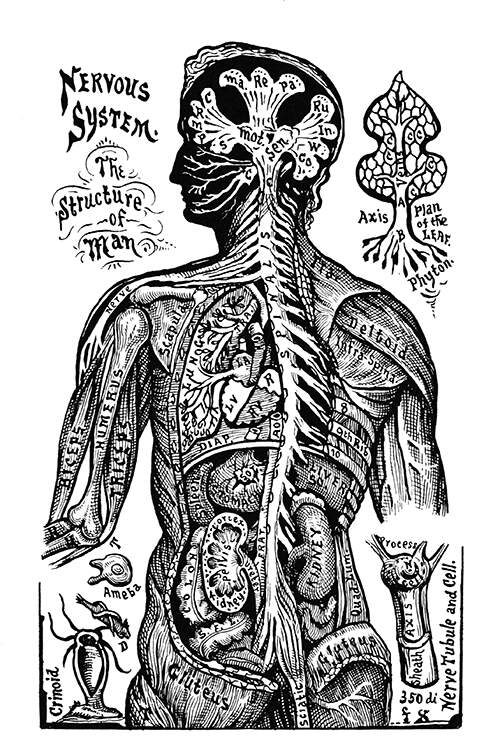

It is easy to think of this as a contemporary issue, a new frontier in theories of the self. In truth, however, humans (at least in the Western-European tradition) have had some sense of the physical nature of the mind for some time. Our mind-body dichotomy has ancient (very ancient) roots but can be derived from multiple sources. One is the thinking of Descartes, who split us into these two hermetically sealed realms (mind or body) and saw the pineal gland as the seat of the soul. As time has gone on, however, different models have come to challenge this. With a rising neuro-humanity model, a new assumption grows: The human is essentially the biological (the mind as wholly material).

Have we crossed a new threshold? Has neuroscience (neuroscience as in the study of the nervous system as a material object, specifically an object producing human experience and consciousness) finally overtaken the humanistic and spiritual traditions of the world? In popular culture, it may well appear that all our greatest problems are on the verge of being solved by chemical means.

This question moves too quickly, however, because it forgets an important part of history. Neuroscience (in the broadest sense) is not new. Neuroscientific models of humanity have impressed upon the Western philosophical and literary imaginations for centuries, with questions regarding the relevance of the brain to models of human experience being re-evaluated regularly.

One place this is evident is 19th century American poetry.

Let’s take a look at the history of this phenomenon I am describing. In academic terms, it is known as the “neural subject,” an assumed theory of self in which we (humans, subjects) are defined primarily through our underlying neural structures. This assumption holds that we are each defined and can be understood as amalgamations of neurons and electrical pulses—we are our brains. Human experience, therefore, consists of sensations mediated through nervous impulses, not sympathies or godly interventions.

An example: What would happen if I put your brain in another body? Most of us (assuming the nerves are not damaged) would say that your consciousness will be resurrected within this new body. Your brain is the seat of your Being and, although one would feel strange in a new body, you would retain your personality and character (the essence of myself). Your immaterial soul and your inherently human spirit are not considered important (or to even exist). This is what we mean by the neural subject.

One can see how this presents problems for discussions regarding the self and what it means to be human. If I can be defined by my brain (and its chemicals), perhaps I simply don’t have a soul. If everything in human consciousness (mystical experience, love, despair, etc.) are all reducible to chemical signals, my relation both to myself and to these emotions changes radically. If I can induce mystical experience with chemicals, then mysticism is bunk; if love is a set of electrical pulses that could be replicated with careful enough technology, love is meaningless; if despair is a symptom of poor brain functioning, the simple solution is to chemically enhance the brain. While these ideas can be challenged despite the neural subject, they are generally not ungrounded. (Even if one disagrees about love being meaningless, one could reasonably concede the point that love is generated through brain activity.) And, when they are unchallenged, they can become assumed parts of our cultural beliefs and drive new emotions. Every now and then we (those who accept the neural subject) each experience a small shock of (neuro)existential dread— “Are all my actions the products of meaningless chemicals bouncing into one another!?”—until we massage, or shove, our concerns away.

Is the neural subject a new idea? In some sense: Yes. Many previous popular models of “what it means to be human” hinged on a psychological or spiritual basis; much of the 20th century was particularly defined by the psychoanalytic model of the subject. Founded through Freud’s work in the late 19th century, Western culture (especially academia) began imagining and focusing on the individual as having a structure of id/ego/superego and being defined by psychic tendencies laid out during one’s formative years. This is a psychological model that thinks of the subject in relation to the structure of their consciousness/mind (not their physical composition). Other popular models of self are humanistic, spiritual, historical, or genetic. Before psychoanalytic theory, however, was the influence of neurology in the 19th century. Here is when models of the self turned sharply towards neurons and the brain for inspiration without the aid of contemporary neuroscientific techniques.

Though theories on the relation of the brain to consciousness have likely existed since the first head injury (it would be suspect, even in 3000 BCE, for a person to change personality after a blow to the head), the formalization of this thinking in the West is first seen in Thomas Willis’ Pathology of the Brain, published in 1667. That is long before fMRI scans existed. From this inception point, this seed, one can trace an expansion of neural subject “prototypes.”

What the 19th century brought was an explosion—a great ballooning in awareness and acceptance—of the neural mechanisms underlying our consciousness. Keep in mind this is some 100 years before the formalization of neuroscience as a discipline in 1963. We can understand that, although the mechanisms of brain function were poorly understood, there was a grasping of the profound idea that human experience is intimately tied to electrical signals (as opposed to spirits or emotions or even neurotransmitters, which had yet to be discovered).

Neurology was well known throughout America, especially circa 1840, where performances and public spectacles using electricity (such as Mesmerism—ie. hypnosis) were widely popular. These performances drew on theories regarding “animal magnetism” and other electrical forces that supposedly directed human actions and experience. Practitioners (magicians or scientists?) would stun audiences by hypnotizing select volunteers into trances, forgetfulness, or convulsions using magnetic objects or their hands.

For several decades, the practice and/or study of neurology was a democratic one that rejected elite control; Mesmerism and neurology were “rogue” sciences that did not function through published journals or certification or accredited education. The field was open to amateurs and doctorates alike till its consolidation began in the postbellum period with scientists, like George Miller Beard, emphasizing medical expertise, biological perspectives, and empirical methods to legitimize the field. This is more akin to our version of Neuroscience (as a field) that requires high levels of education, peer review, and a host of other qualifications before publishing work and that tends towards a biomedical(ized) view of human experience.

Returning to mid-to-late 1800’s America, the reactions to this popular neurology were widespread. Nathaniel Hawthorne advised his daughter against medicine to prevent migraines, as it might contaminate her soul (and prevent entry to heaven) [i]; Edgar Allen Poe and others rejected the idea that physical nerves were proof against God or the spiritual. Overall, however, this popularity allowed the physiology of nerves to become public knowledge and for the language of nerves/brains/electricity to become commonplace.

What Poe and others saw in this 19th-century neurological approach was a potential rejection of the purely material subject. In this imagination, Electricity was not codified as a simple physical phenomenon, but in multiple dimensions as “a material fluid, spiritual medium, [and] a disembodied force” where “its metaphoric and symbolic use to represent the human potential to harness the natural world” became clearer [ii]. Electricity could both connect people to each other and the universe while also retaining “its power and its potential to disconnect [us] from the world and from the larger community” [iii]. This force “seemed to bridge the spiritual and the material, the natural and the technological… It seemed to be imponderable—lacking in weight and mass and everything else that would seem to distinguish matter—yet it also seemed to pervade all matter” [iv].

While the 19th century may accept physical construction of the body to be a limitation on the mind, the use of electricity as a medium and force that worked between material and spirit allowed electricity to become an image of how the physical body transcends into spiritual existence, an explanation for how it is that spirit is tied and interchanged with matter.

Now, onto the poems.

Let’s see what the metaphysician herself, the esteemed Emily Dickinson, can show us. We’ll look at a set of poems written between 1862 and 1865. Her command over philosophy and theology through poetry is generally astounding, so what does Dickinson have to say about the brain, about electricity?

Starting with… Nerves!

If your Nerve, deny you—

Go above your Nerve—

He can lean against the Grave,

If he fear to swerve—

That’s a steady posture—

Never any bend

Held of those Brass arms—

Best Giant made—

If your Soul seesaw—

Lift the Flesh door—

The Poltroon wants Oxygen—

Nothing more—

This poem is punctuated, to say the least—dashes extending out and keeping her phrases hermetically sealed. Yet, Dickinson asks us to read the phrases together. How can a nerve deny us? How presumptuous of my constituent parts to deny their sovereign the right to dominate! But, unfortunately, we are reminded that our constituent parts are not our own—their matter exists separate from our Will. If our nerve (our courage, our ability, our strength, our intellect, our romance) is to fail us, we must… breathe! I’m reminded of “Keep Calm and Breathe” here but our poet isn’t so jocular about the matter. She is detailing the basis of our emotional and spiritual states. All the volumes of philosophy, all the doctrine and dogma regarding the soul, all the rituals meant to help protect our religion are meaningless without breathing (more directly, without Oxygen).

Hear her contempt! And shouldn’t we also feel the same? All our sensitive feelings, our deepest spiritual convictions, our strongest affections are all dependent upon the continual mechanism of the in-out-in-out of the Oxygen-Carbon Dioxide system. We can hear some Platonic sneering at the flesh; that poltroon of a nervous system wants Oxygen—Nothing more—and is willing to throw all our metaphysics and religion to the dust if we don’t supply it: A real hostage situation!

The original question still stands, however, but Dickinson isn’t much help. If our nerves fail us… simply go above them. Go above? Above my nerves? I presume she means to go to another nerve, given that nerves are of a “steady posture,” more willing to go to “the Grave” than to swerve. To rewire a neuron or synapse is much more costly than to simply pare it, which is partly why so many of our synapses are pruned when we are children—they just take up too much space—and Oxygen.

If that’s what we need to know about the nerves, Dr. Dickinson, what about the brain?

The Brain, within its Groove

Runs evenly—and true—

But let a Splinter swerve—

‘Twere easier for You—

To put a Current back—

When Floods have slit the Hills—

And scooped a Turnpike for Themselves—

And trodden out the Mills—

Hm… I know some brains that don’t run evenly or true, but I’ll drop the matter for now. Dickinson is referring to the Ideal brain, I assume.

Grooves—technically referred to as sulci—are the great distinction of our folded brain. Within the groove (within the normal path, the known route, the established road), the brain runs evenly—constantly, without disruption, smoothly—and true—accurately, straight-forwardly, faithful-to-reality. Hark—a Splinter! Who knows where it has come from: from within or without, the splinter has diverted our course—to the helm, we are swerving! And so, our brain suddenly shifts directions and directionality, reality is uneven, our processing is unfaithful. (Was it ever faithful?) Our perception is warped, twisted—taken for a loop.

And, according to the good doctor, don’t attempt to put it back. It would be easier to put hills and mills back together after being wrought by a flood. The landscape of the mind has been scooped, a current (electrical, intellectual, spiritual) has left an indelible mark in consciousness. No medicine can take a splinter out of the mind!

Well… I will certainly be wary of any splinters entering my mind. (Or, maybe the fun is in the flood?) Regardless, my seasonal depression is returning this Winter and I need Dr. Dickinson’s remedies.

I’ve dropped my Brain — My Soul is numb —

The Veins that used to run

Stop palsied — ’tis Paralysis

Done perfecter on stone

Vitality is Carved and cool.

My nerve in Marble lies —

A Breathing Woman

Yesterday — Endowed with Paradise.

Not dumb — I had a sort that moved —

A Sense that smote and stirred —

Instincts for Dance — a caper part —

An Aptitude for Bird —

Who wrought Carrara in me

And chiselled all my tune

Were it a Witchcraft — were it Death —

I’ve still a chance to strain

To Being, somewhere — Motion — Breath —

Though Centuries beyond,

And every limit a Decade —

I’ll shiver, satisfied.

I’ve dropped my brain and can’t get up: A clear case of depression—the soul is numb. The strength of the connection between the two is obvious: drop a brain (take a bad fall, catch a bout of depression, or have degenerating brain tissue) and you will have a numb soul.

Paralysis with blocked veins is a simple diagnosis: ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. But, could this not also be depression? I have dropped my brain (my poor serotonin levels—fallen); how shall I pick it up again? (Why, try an SSRI!)

(The doctor says we are sticking to stroke, but I say the depression connection is significant.)

Dickinson’s poetry draws together the strings attached to this terrible disease: the physical basis (veins) and the spiritual effect (numbness). Despite being a breathing woman, our patient is now reduced to a carved (physically existent) yet cool reality; our brains (and accompanying nervous systems) are not merely ways of controlling our body—they are the path to Paradise (with a capital P!). The body and its electrical signals in their active engagement with the world are the basis of Paradise, which we only realize once we have lost their ability.

But fear not, our patient is not dumb (she retains intellect, speech—no signs of aphasia). Despite what caused the malady, Witchcraft or Death (Witchcraft in a scientific age?!), the soul within (nerves still intact) can still strain, can still dream to Be—to have motion and to breathe—the two fundamentals of animal life. Though time has slowed to a crawl, each year a decade and each decade a century, if she can move and breathe just once more she can shiver (and die?) satisfied.

The brain is intimately tied to our soul, interwoven with our physical and emotional abilities. Drop the brain and you drop your soul, in a certain sense; my depression can be physically manifested (a new development in the theological mindset).

If my soul is physically dependent, however, I can’t help but feel trapped. There is no meaning, it seems, to the soul, or good will, or faith if my emotions and reality are simply the constructs of an organic mass of neurotransmitters. Let’s hear what Dr. Dickinson has to say:

This is a Blossom of the Brain —

A small — italic Seed

Lodged by Design or Happening

The Spirit fructified —

Shy as the Wind of his Chambers

Swift as a Freshet’s Tongue

So of the Flower of the Soul

Its process is unknown.

When it is found, a few rejoice

The Wise convey it Home

Carefully cherishing the spot

If other Flower become.

When it is lost, that Day shall be

The Funeral of God,

Upon his Breast, a closing Soul

The Flower of our Lord.

The Brain and its Ideas are a Blossom. They can be lodged by design (Creation) or happening (Evolution)—either way, it is the spirit fructified. (What a delicious sentiment!) The flower of the soul, both the product and the substance of the neural matter, is hidden to us.

When we find this flower—the brain—a few will rejoice; the wise recognize it as Home: Home is where my brain is! Cherish the blossom (pink and effulgent), don’t deny it; the day we lose the Brain will be the day we mourn the death of God. The closing of the soul of God coincides with the loss of our souls, the spirit of our minds.

The Brain as the Flower of God and God as the Seed born within the mind. (Unfortunately, the Brain does not smell like other flowers—I still raise my nose at formaldehyde.) In this way, God is born from our mind and, through God, the brain is born. This symbiosis of sorts reveals the delicate interplay between the physical and the metaphysical—we can be neuroscientists (like the good Dr. Dickinson) and spiritualists!

The real question, however, is how the brain mediates between the physical substance and the spiritual plane. In this sense, we have to look at the fundamental assumption of the neural subject: that human action, emotion, and thought are driven by electrical pulses (in our 21st-century world, we recognize neurotransmitters as the signaling mechanism).

Then, what does Dr. Dickinson have to say about the power of electricity?

The Lightning playeth — all the while —

But when He singeth — then —

Ourselves are conscious He exist —

And we approach Him — stern —

With Insulators — and a Glove —

Whose short — sepulchral Bass

Alarms us — tho’ His Yellow feet

May pass — and counterpass —

Upon the Ropes — above our Head —

Continual — with the News —

Nor We so much as check our speech —

Nor stop to cross Ourselves —

Lightning (electricity in its grandest outfit) is always playing—note the personification. Only when he sings (BOOM! Thunder shocks us) do we realize He (capital H—similar to God) exists. And, being as silly as we humans are, we take the task of approaching this god. We do so sternly—seriously, carefully, unimaginatively—using our empirical method, with insulation and gloves to protect us. No one dares to work on electricity without insulation.

Though his sepulchral—heavenly, sky-born—Bass shocks us (Thunder, Thunder, Thunder!), Lightning’s feet move swiftly and silently (pass, counterpass, pass) upon the Ropes (ropes, ties, bonds… nerves?). Lightning flashes in the sky above us without our knowledge but also above us in our brains, firing and freezing between neurons regularly, so as to match the “News”; all the new information we absorb from the external world must be decoded and recoded and encoded with a million small zaps. In fact, this electricity fires so quickly we have no time to check our speech or ask for divine protection before He moves from one neuron to the next to the next to the next…

For us in the modern day, we wouldn’t see the yellow feet of Lord Lightning passing within our minds. Instead, we imagine the colorful play of neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine). Chemicals don’t constitute a medium, but appear as contained units; perhaps this language of individualized molecules (as opposed to the stream of electricity) contributes to our modern despiritualized view of the nervous system. Neurotransmitters are clumsy and physical and easy to visualize; we build models of neurotransmitters, learn their chemical qualities, and synthesize agonists and antagonists to shift the tides of neurochemical war. Electricity, however, remains mysterious, invisible, and ineffable—Divine.

Neurotransmitters, however, are not wholly divorced from Lord Lightning. They function by regulating the generation of electrical current; electron transfer is key to neurochemical functioning. There remains a connection, thereby, to electricity—a force of Nature beyond ourselves. This same force that circulates and moves through our skulls exists in the clouds (the heavens), coming down in large bolts to burn the earth and in our technology, creating a web of instant communication across the globe. We owe electricity a great deal for tying our world together: our brains, our screens, and our skies.

And, of course, our souls.

Let’s review the conclusions from our neuro-poetic dissection. While it is common-place to refer to the Brain and its components as existing only in a material field today, the 19th century found vitality and agency and divinity within the function and energy and beauty of the nervous system. What we see as electricity (or, more technically, neurochemical signaling) was for them a sign and material process of phasing between the physical, mental, and spiritual. Electricity cannot be contained or confined and exists beyond the physical plane; if we learned to respect it as they did, perhaps our own vision of the neural subject wouldn’t be so terribly material but might be able to transcend the body through the body.

____________________________________________________________________

Endnotes:

[i]. Murison, 42

[ii]. Gilmore, 6

[iii]. Gilmore, 7

[iv]. Gilmore, 7

Bibliography:

- Dickinson, Emily. “The Brain, within it’s Groove.” The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by R. W. Franklin, Belknap Press, 1999, pp. 254.

- Dickinson, Emily. “If your Nerve, deny you—.” The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by R. W. Franklin, Belknap Press, 1999, pp. 147.

- Dickinson, Emily. “The Lightning playeth—all the while—.” The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by R. W. Franklin, Belknap Press, 1999, pp. 267-268.

- Dickinson, Emily. “This is a Blossom of the Brain—.” The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by R. W. Franklin, Belknap Press, 1999, pp. 449.

- Dickinson, Emily. “I’ve dropped my brain—My Soul is numb—.” The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by R. W. Franklin, Belknap Press, 1999, pp. 440.

- Gilmore, Paul. Aesthetic Materialism: Electricity and American Romanticism. Stanford University Press, 2009.

- Mills, Bruce. Poe, Fuller, and the Mesmeric Arts : Transition States in the American Renaissance. University of Missouri Press, 2006.

- Murison, Justine. “‘The Paradise of Non-Experts’: The Neuroscientific Turn of the 1840s United States.” The Neuroscientific Turn: Transdisciplinarity in the Age of the Brain, edited by Melissa M. Littlefield and Jenell M. Johnson, University of Michigan Press, 2012, pp. 28-48.

- Smith, Matthew Wilson. “Introduction.” The Nervous Stage: Nineteenth-century Neuroscience and the Birth of Modern Theatre. Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 1-16.

- Smith, Matthew Wilson. “The Emptying of Gesture.” The Nervous Stage: Nineteenth-century Neuroscience and the Birth of Modern Theatre. Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 1-16.

- Smith, Matthew Wilson. “Conclusion.” The Nervous Stage: Nineteenth-century Neuroscience and the Birth of Modern Theatre. Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 1-16.

- Smith, Matthew Wilson. “The Emptying of Gesture.” The Nervous Stage: Nineteenth-century Neuroscience and the Birth of Modern Theatre. Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 1-16.