Are highly rated Environmental, Social, and Governance (“ESG”) firms more transparent about their risk exposures stemming from their activities abroad? Does investing in more highly rated ESG firms, i.e., those that are alleged to be more socially responsible, imply contributing to more socially responsible actions abroad? And does investing in such firms insulate one from the financial fallout of a major geopolitical shock? In a recent study, we use the Russian invasion of Ukraine to reveal the usefulness (or lack thereof) of ESG ratings for assessing firms’ socially responsible behaviors abroad.

Trillions of dollars in capital are allocated to highly-rated ESG firms, and the billion-dollar ESG ratings industry provides numerous ESG subcomponent and summary scores to support the capital allocation decisions of professional and retail investors alike. What are these ESG ratings supposed to measure? MSCI states that its ESG scores measure a firm’s “management of financially relevant ESG risks and opportunities,” while Refinitiv measures a firm’s “ESG performance, commitment, and effectiveness.” Moreover, some academics and practitioners have perpetuated claims that investing in highly rated ESG firms leads to both superior returns and lower risk. In short, ESG investing is alleged to be the best of both worlds: doing well while doing good. But how well do these claims hold up when it really matters?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24th and the subsequent Western public outrage, sanctions, and corporate exodus together represent an adverse outcome stemming from firms’ operations in a country with a blatant disregard for human rights, high levels of corruption, poor corporate governance, and a severe neglect for the environment. Even before accounting for the atrocities committed by Russia in Ukraine and Russia’s breach of the international rules-based economic order, the World Bank consistently ranked Russia very poorly on its six worldwide governance indicators, while Russia is perceived as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, ranking as the 44th most corrupt country out of the 180 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

Using a wide variety of sources, including firms’ pre- and post-invasion filings, Factiva news searches, and the Yale Russian Business Retreat list, we cast a comprehensive net to identify European Stoxx 600 firms with Russian exposure. We collect data on the materiality of their Russia-related exposures, the extent of their pre-invasion Russia-related disclosures, as well as their post-invasion corporate responses and financial performance, and we merge these data with ESG ratings from Refinitiv, MSCI, and five other large ratings providers. The map in Figure 1 summarizes the average Stoxx 600 firm’s Russian exposure for each country included in the Stoxx 600 index. The graphic suggests that the extent of Russian exposure, as measured by the percentage of Russian sales, assets, net income, or employees, is roughly proportional to a country’s geographic proximity to Russia, with firms headquartered in Finland, Poland, Austria, Denmark, and Italy facing the largest average exposure.

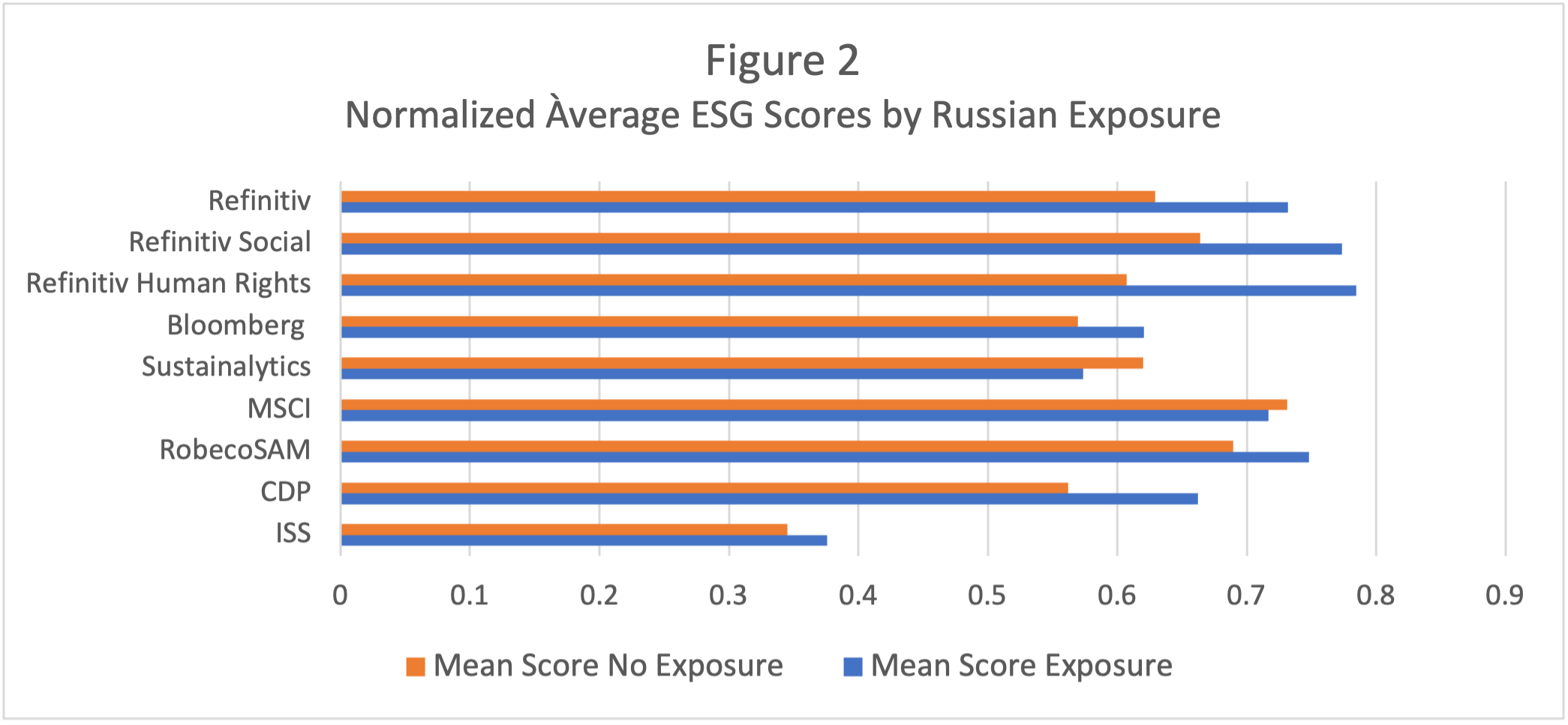

Even before the atrocities and war crimes committed in Ukraine, Russia was known for its corruption, poor corporate governance, environmental unfriendliness, and human rights violations. Our first set of analyses therefore investigates whether highly-rated ESG firms were less likely to be operating in Russia prior to the invasion, and whether highly-rated ESG firms with operations in Russia were more likely to be transparent about their activities in this geopolitically risky zone. Neither turns out to be the case. Figure 2 shows that none of the ratings agencies assigned meaningfully lower ESG scores to firms with Russian exposures, while 5 out of the 7 ratings providers assigned higher scores to firms with Russian exposures. Strikingly, given Russia’s dire track record on human rights, Refinitiv assigned Social and Human Right scores that were 15% and 30% higher, respectively, to Stoxx 600 firms operating in Russia relative to peer firms that avoided such activities. These results hold up in regression analyses that control for a host of financial variables, and country and industry fixed effects. After controlling for such factors, we additionally find that highly-rated ESG firms were not more transparent about their Russian operations in pre-invasion annual and sustainability reports. Relying on companies’ voluntary disclosures related to their activities abroad, particularly in countries that are corrupt, abusive of human rights, or that otherwise embody significant ESG and geopolitical risks, may leave investors underinformed and ultimately financially exposed. Furthermore, in the absence of adequate corporate disclosures, our findings indicate that high ESG scores do not serve as a substitute source of information related to such risks.

In our second set of analyses, we focus on the corporate exodus from Russia. From the massacre in Bucha, to the indiscriminate shelling of civilian buildings, and the deportation of Ukrainian nationals, Russia’s actions in Ukraine demonstrate an utter disregard for human dignity and international law. Are highly-rated ESG firms, those alleged to behave in a more socially responsible manner, more likely, or quicker, to suspend or divest their Russian operations in response to the invasion? Using duration analysis and logistic regressions, we find that, across all 7 ratings providers, highly rated ESG firms were neither more likely, nor quicker, to suspend or divest their Russian operations. Instead, larger, more profitable firms, and those with higher pre-invasion cash holdings were quickest to divest or suspend their Russian operations. In short, our results suggest that decisions as to whether, and how quickly, to divest or suspend Russian operations are largely driven by financial variables. More highly-rated ESG firms were neither more likely, nor quicker, to distance themselves from Russia despite the tremendous ESG and human rights implications associated with continued business operations in Russia.

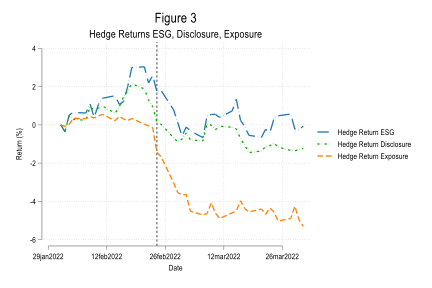

Taken together, our results indicate that, in the context of Stoxx 600 firms with activities in Russia, the “doing good” part of investing in highly-rated ESG firms certainly did not hold up. Were investors in such firms at least better protected against the stock market turmoil surrounding the invasion? Did investors in highly rated ESG firms at least do “well”? Figure 3 shows the cumulative hedge returns of three portfolios over the period February 1st to March 31st, 2022. The first portfolio (blue and long-dash-dotted line) takes long positions in firms with top quartile ESG ratings and short positions in firms in the bottom quartile of ESG ratings. The second portfolio (green and short-dash-dotted line) takes long positions in firms with more meaningful disclosures about their pre-invasion Russian activities and short positions in those firms that are less transparent, while the third portfolio (orange and dashed-line) takes long positions in firms identified as having Russian sales or assets and short positions in firms without any Russian operations. As is evident from the graph, around the date of the Russian invasion on February 24th, Stoxx 600 firms identified as having Russian operations significantly underperformed their counterparts without Russian operations. Investors in highly-rated ESG firms were not insulated from the stock market fallout, and investors in more transparent firms faced additional losses relative to those having invested in less transparent firms. In regression analyses that control for a host of market-based measures of risk and other financial variables, we find that a one-standard deviation increase in Refinitiv ESG, Russia-related disclosures, and Russian exposure, is respectively associated with an additional 20%, 19%, and 32% decrease over the mean Stoxx 600 firm return of -7.5% from February 24th to the week after the invasion. Evidently, investors in highly rated ESG firms did not do “well,” while those investing in more transparent firms suffered greater losses than those investing in firms that were less forthcoming about their Russian operations.

The corporate exodus from Russia is crippling the Russian economy, and it significantly affects Putin’s ability to fund his war efforts. But in a context where socially responsible behaviors could really have made an impact, ESG failed to deliver; highly-rated ESG firms were neither more likely to exhibit more socially responsible behaviors abroad, nor were they more likely to be transparent about their operations in a rogue country. Our results have several practical implications beyond the Russian-Ukraine context. First, ESG risks stemming from firms’ operations abroad are becoming ubiquitous. For example, China’s actions in the Indo-Pacific region have raised alarms in corporate board rooms; Volkswagen is facing considerable pressure surrounding human rights violations in Xinjiang; and many other firms are facing moral decisions about whether to be associated with Qatar’s World Cup, or Saudi-Arabia’s “sportswashing” in the context of the LIV golf league. Second, ESG risks stemming from firms’ international operations are financially material considerations for (responsible) investors, but ESG ratings agencies have failed to adequately weigh and incorporate such considerations into their scoring systems despite country-level measures of human rights violations and corruption being freely and readily available from authoritative sources such as the World Bank. Third, just one day before the invasion, the EU introduced the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (“CSDD”). The CSDD aims to increase transparency and mitigate adverse human rights and climate impacts in firms’ value chains. The directive will impact all large EU firms, as well as non-EU companies that are active in the EU. Our findings that highly-rated European firms with Russian exposure were not more transparent about their Russian activities and that investors in firms with Russian exposure faced substantial losses indicate that such regulation may be beneficial not only to socially responsible investors, but also to those who are solely focused on financial risks and returns. Regulators outside of Europe – e.g., the Securities and Exchange Commission in the U.S. – would therefore be wise to take note and to consider whether existing disclosure requirements related to companies’ activities abroad are sufficiently informative for investors.

Daniyal Ahmed is a Manager at PwC.

Elizabeth Demers is a Professor of Financial Accounting at the University of Waterloo School of Accounting and Finance.

Jurian Hendrikse is a PhD candidate at the Tilburg School of Economics and Management.

Philip Joos is a Professor of Accounting at the Tilburg School of Economics and Management and TIAS School for Business and Society.

Baruch Lev is the Philip Bardes Professor Emeritus of Accounting and Finance at NYU Stern.

This post is adapted from their paper, “Are ESG Ratings Informative About Companies’ Socially Responsible Behaviors Abroad? Evidence from the Russian Invasion of Ukraine,” available on SSRN.