Do friends provide good financial advice that helps inexperienced investors earn a higher return in the market? Or do friends provide bad advice that leads to excessive investments in individual stocks and asset bubbles? In a new study, we provide evidence that new investors copy the portfolios of their friends and that the advice was, on average, good. Investors with worse portfolios tended to give worse advice, whereas good investors gave good advice. In short, instead of going to an investment advisor, you can rely on your friends for advice, but make sure your friends are good investors first!

While there is considerable evidence that social connections influence participation, we do not know as much about the quality of our friends’ advice. Do friends spread information about the general benefits of participating in risky assets? Social connections would then increase stock market participation and reduce the costs of non-participation, an extensively studied mistake. Alternatively, maybe our friends spread information about individual assets? In this case, the quality of advice becomes paramount: bad advice could facilitate investments into specific assets or asset classes like cryptocurrencies or `meme’-stocks, leading to investment mistakes at the individual level and potential asset bubbles at the macro-level. Alternatively, good advice could reduce idiosyncratic risk and improve portfolio quality, for example, by spreading information about investments in mutual funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

Understanding How Peer Effects Operate

We study data from a referral campaign from an online brokerage in Germany, allowing us to observe peer relationships and the portfolio composition of a sample of investors. The peer relationship consists of individuals who recommend (Recommender) their bank and brokerage to an acquaintance (Follower). This dataset allows us to circumvent two major challenges in studying peer effects. The first challenge is that social ties generally are unobservable, which forces other researchers to rely on assumptions about the nature of peer relationships, for example, by grouping individuals based on working environment, family ties, or geography. The second challenge is that we need detailed portfolio composition to evaluate the performance of the resultant portfolio and investment outcomes. As such, much of the existent literature has focused on participation in risky assets or specific investments. We link Recommenders and Followers to detailed data on portfolio composition and study how the Recommender’s portfolios affect the Follower’s portfolio.

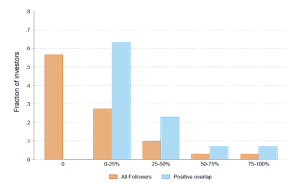

Figure 1: Overlap between Followers and Recommenders.

Figure 1: Overlap between Followers and Recommenders.

Notes: The figure shows the distribution of the number of investors by the average share of peer-determined securities in their accounts. The portfolio for the Recommender is lagged one month relative to the Follower.

For each Follower-Recommender pair, we construct a measure of the overlap in their portfolio. The overlap is simply the percentage of assets of the Follower shared with the Recommender. The average overlap share is approximately 20 percent but varies considerably among Recommender-Follower pairs. Figure 1 shows that for Followers with a positive overlap share, 30 percent share between 75 and 100 percent of their portfolio with their Recommender, indicating that the peer is the primary source of information about which assets to invest in within this group. The investors in our sample have access to over 900,000 different assets, meaning that the probability that individual investors end up with the same portfolio by chance is minuscule, even when we condition on shared factors such as demographics, investor traits, or geography. We conducted several placebo tests to alleviate concerns that the overlap share does not occur by chance or by an unobserved factor.

This first set of results helps us understand how peer effects operate. One possibility is that social connections spread information about the general benefits of participating in risky assets. Social connections would then increase stock market participation at the extensive margin and reduce the costs of non-participation. If this were the case, we would not observe such a large overlap in portfolios between Recommenders and Followers. Instead, our results indicate that investors learn about specific assets from their social connections.

Personal connections help spread valuable information

We now turn toward the question of the quality of the advice. Since social connections spread information about individual assets, the quality of advice becomes paramount. Bad advice may facilitate investments in specific assets or risky asset classes such as cryptocurrencies or meme stocks, leading to investment mistakes at the individual level and potential asset bubbles at the macro-level. On the other hand, good advice could help by reducing idiosyncratic risk and improving the overall quality of investors’ portfolios by spreading information about investments in low-cost mutual funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

We first document that Followers hold more diversified portfolios than the average new investor. When we look at Followers with a non-zero portfolio overlap, we find that they build portfolios with a lower return loss. The return loss measures the average return the investor foregoes by choosing their portfolio instead of a position that combines the benchmark index with cash to achieve the same risk level. When we dig further into what drives the lower return loss, we find that Followers tilt their portfolios further towards equities, have a higher portfolio beta, and a lower diversification loss than other investors.

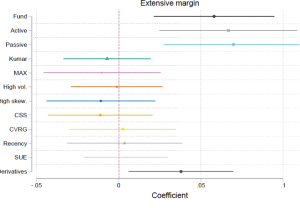

Why do the Follower-Recommender pairs end up with better portfolios? The lower diversification loss of Followers is rooted in their investment strategies. Figure 2 plots the coefficient on a Follower-dummy from regressions on participation in specific asset classes, showing how Followers differ in their asset class participation from a general sample of new investors during the same period. Followers are about five percentage points more likely to invest in funds than other new investors, even after controlling for a wide range of individual and location-specific characteristics, a sizeable effect. We then examine investment in lottery stocks, attention stocks, derivatives, and structured retail products. Such securities are arguably detrimental to portfolio quality and are empirically associated with higher return losses in our sample. In addition, Bing Han, David Hirshleifer, and Johan Walden study the transmission of ideas where senders are more likely to report their successes and argue that high skewness or lottery-like stocks are more likely to transmit to other investors. We show that Followers are equally likely to invest in lottery stocks as the general sample on the extensive and intensive margin. Finally, Followers are more likely than average to invest in high-risk derivatives and structured retail products.

Figure 2: Asset type participation for Followers compared to other new investors

Notes: The figure compares investments in specific asset classes for Follower and the general sample. The figure plots the coefficient on Follower along with 95 percent confidence intervals. Control variables include a dummy for male, income proxy, academic title, age, and age squared, as well as controls for having our bank as the main bank and a dummy equal to one if the account is a joint account.

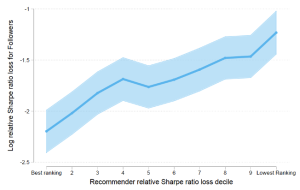

Strong Correlation in Portfolio Quality Between Follower and Recommender

Does it matter who your friends are? Our answer is yes. We show a strong correlation in portfolio quality between Followers and Recommenders. We sort Recommenders into deciles of log Relative Sharpe ratio loss and then compare the portfolio quality for Followers across deciles, showing a strong linear relationship between Recommender rank and Follower portfolio quality. Figure 3 shows an almost linear relationship between Recommender rank and the value for the Follower. The mechanism underlying this result is that the Follower is likelier to invest in funds if the Recommender invests in funds. Since investing in funds is correlated with higher portfolio quality, this leads to a higher quality portfolio for both Followers and Recommenders. The implication is that it matters who gives the advice, especially since it tends to concern specific assets. If your friend is a good investor, following their advice will likely benefit your portfolio quality. However, there is also scope for bad advice to spread through social networks. The quality of the investors providing advice is paramount.

Figure 3: Follower portfolio quality conditional on Recommender portfolio quality

Notes: The figure plots the Log Relative Sharpe Ratio Loss for Followers against their Recommender rank decile. 95% confidence intervals are provided.

Welfare Implications Depend on Learning Versus Copying

Distinguishing between learning and pure imitation is important for understanding the welfare effect of peer effects. Is the peer effect we uncover simply the result of pure imitation, or is there a transfer of knowledge and learning? With the (large) caveat that it is difficult to distinguish learning from imitation, we argue that our findings suggest that learning takes place. With learning, Recommenders act as money doctors and improve financial outcomes by helping Followers make more informed decisions about their financial investments. With (mindless) imitation, Followers simply copy the portfolio without regard to their preferences. The welfare implications of mindless imitation would also be unclear, as the preferences of Recommenders and Followers may differ. What is right for the Recommenders may not be right for the Follower. Given that Followers tilt their portfolios towards passive funds to a greater extent than lottery or attention stocks, it seems unlikely that Followers copy their peers solely to generate social utility.

Conclusion

In sum, we provide new evidence that social connections help spread information about individual assets. Our results suggest that social connections can propagate good and bad investment behavior, depending on the quality of advice. We conclude that in our setting, the “good” investment advice of the peers outweighs the “bad” investment spillovers and leads to higher quality portfolios for the followers.

Olga Balakina is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics and Business Economics at Aarhus University.

Claes Bäckman is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics and Business Econmics at Aarhus University.

Andreas Hackethal is a Professor of Finance at Goethe University.

Tobin Hanspal is an Assistant Professor of Finance at WU Vienna University of Economics and Business.

Dominique Lammer is Head of Corporate Strategy, Marketing, and Digital Transformation and the Chief Digital Officer at DZ Privatbank.

This post is adapted from their paper, “Good Peers, Good Apples? Peer Effects in Portfolio Quality,” available on SSRN.