In the West, the white female body simultaneously symbolizes promiscuity and purity, Liberty and docility. It is the body at the foreground of the women’s suffrage movement (due to middle class white women’s exclusion of other bodies) and in the background of Fortune-500 companies. It is equality in the books and inequality in the real world. It is my body and it isn’t my body.

Half-Western European, half-Cuban, I am sexualized as a white female with “Latin spice”. I have smiled shyly at burly strangers on airplanes when they have offered to lift my carry-on suitcase into the overhead bin. I have kept my cool as men have asked me to “prove” I have a Spanish accent. I have heard my peers question both my merit and my ethnicity when they told friends of mine that I only got into Duke because I am a Hispanic female. I experience the world as a female first, a Hispanic second, and a ~transcendent human being~ third, while my male peers experience it in the reverse order.

Representations of the white female body are inescapable. I went to four museums this week, and each represented the female body in a slightly different way. The Museum of Sex offered mostly heterosexual portrayals of nineteenth-century pornography, animal sex, and a history of sexual objects, all of which related the (mostly white) female body-as-sex-object to another sexual object or a male sexual partner. The first floor of the museum, a “sex shop” that almost exclusively sold embellishments to the female body-as-sex-object, was no better.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I saw three distinct portrayals of nude white female bodies that I will describe below.

- The Demure Enchantress

In Henri Lehmann’s Study of a Female Nude, a white woman bends over her partially covered legs to conceal her nude body, revealing the curvature of her back and one of her breasts while gazing directly at the spectator. The female body is portrayed as an object of shame, to be hidden as much as possible, but it shames only her; the spectator and the artist can enjoy it as a sexual object. It is difficult to glean much from her facial expression other than her outward gaze because she covers most of her face with her arm. Lehmann has deprived her of internality by shielding her expression and rendering her as a subject vulnerable to the spectator’s gaze.

Fun fact: Lehmann described the subject of this painting in a letter to his mistress as one of the “four most beautiful girls you could have as a model in Rome.” Thanks for your input, Lehmann. We don’t really care what you think.

- The Hairy Venus

Gustave Courbet’s The Woman in the Waves invokes Cabanel’s Birth of Venus and adds a little bit of armpit hair, subverting the image of the hairless nubile woman and representing the subject of the painting as more “human” than other nude subjects I have seen. Courbet’s attention to detail in his portrayal of the white female body is another refreshing departure from the way white females used to be painted.

Fun fact: Keeping one’s body hair might be an act of feminist resistance and power for some (white) women, but not all of them. Check out this article about what shaving means for women of color.

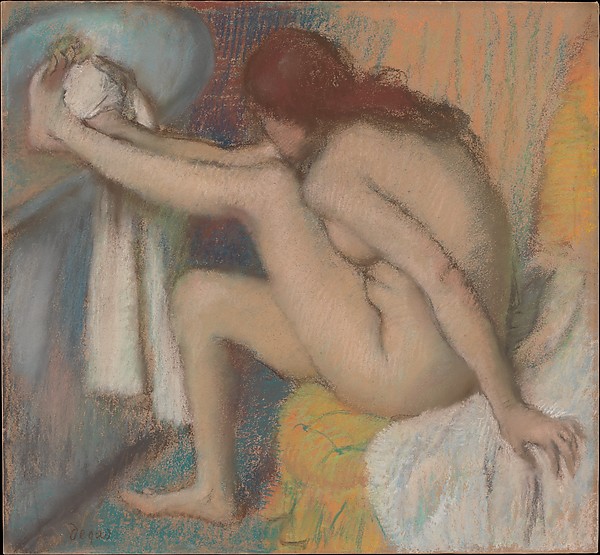

- The Apathetic Bather

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, Edgar Degas represented nude female women in their performance of daily activities, like bathing. The comparison between Degas’s Woman Drying Her Foot and the nude representations I’ve already mentioned is just laughable—the female body is not made to symbolize anything except what it is, at least on the surface.

Fun fact: Degas produced a series of brothel scenes in the 1870s that portrayed the female workers as apathetic and the male clients as unsure of themselves, returning some of the power that male dominance has taken away to the sex workers.

In his book Ways of Seeing, John Berger says that “To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself.” I couldn’t agree more with his analysis in the context of Western art. Degas embraces the physicality of the white female body while maintaining the humanity of his subjects. His sketches show a deep attention to the study of the characters his paintings and sculptures portray. In his nude studies of some of his sculptures, he stripped his subjects down to better understand them, not to simplify them as sexual objects. While Lehmann and Courbet appropriate the white female body for their art, Degas appreciates the white female body and explores it in motion.