Brielle Tobin and Barbara Lynn Weaver

Health and Socioeconomic Disparities of Food Deserts

Food insecurity exists when communities experience inconsistent access to adequate food due to lack of money and other resources. While especially relevant in today’s social climate, food insecurity in and of itself it not a new issue. Historically, there have always been parties who don’t know where or when their next meal will happen, such as early hunter gatherers. However, despite the time elapsed since we transitioned from a nomadic lifestyle, one in six Americans still experience food insecurity, either lacking funds to provide food or lacking access to food (Hartman). The latter can be described using the term food deserts, which are defined as “households being more than a mile from a supermarket with no access to a vehicle” (Chinni). The most recent societal transition from urban life to suburban life has exacerbated food insecurity as wealthy families move out of cities, and grocery stores move with them. For families with cars, this spread of resources doesn’t create a problem, but for families without transportation, the distance to the grocery store, and therefore access to food, can become impassable.

In areas such as Durham, North Carolina, where a history of redlining defines and restricts economic opportunities for all households within specific areas, families must rely on supermarkets and grocery stores that cater to low-income budgets for nutritious meals (Michaels). Redlined districts were originally based on racial division, and those within the districts were and still are deliberately denied loans based simply on the area in which they live. As a result, private transportation is often a luxury that only those of higher socioeconomic status, or those living in higher graded districts, can achieve. Grocery stores that carry the healthiest food are also oftentimes the most expensive. Consequently, chains such as Whole Foods are focused in areas of higher wealth, like suburbs, where families that can afford cars and gas can also afford the more expensive goods. The need for transportation and mobility to reach nutritious food is then the first barrier between a well-rounded dinner for four and items off the four for four menu at a fast food restaurant.

As demonstrated by redlining, low income populations facing discrimination are almost always populations of minorities. These populations are more likely to be living in areas affected by food deserts. For example, the United States Department of Agriculture states that, “the percent of the population that is non-Hispanic Black is over twice as large in urban food deserts than in other urban areas” (Dutko). A history of oppression coupled with increasing economic disparities creates areas of poverty in which food deserts appear. This causation is evident in the specific locations of grocery stores, as stated in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine: “Studies have found that wealthy districts have three times as many supermarkets as poor ones do, that white neighborhoods contain an average of four times as many supermarkets as predominantly black ones do” (Morland). Distinction between white and/or wealthy neighborhoods and lower income communities with minorities is not a new phenomenon; however, the issue of food security is a pertinent and daily battle in which every person regardless of wealth or race must participate.

Discrimination in terms of supermarket placement is not solely found in densely populated cities, as food deserts outside of urban areas also present immense obstacles for rural communities. For instance, the subject of food sovereignty is prioritized in numerous Native American communities. An exemplification of this issue is the Oglala Lakota people of South Dakota’s Pine River Reservation who rely on 95 percent of their goods to be shipped in from outside of the Nation (Elliot). The dependency caused by this food desert restricts the lives of those within the community and prevents communities from maintaining their independence. The experiences of people living within urban and rural food deserts establishes the pressing matter of food deserts as an environmental justice issue. Withdrawing access to goods from specific communities based on race and income rejects the rights for all to lead safe and healthy lives, and stresses the increasing importance of providing equal opportunities for adequate food.

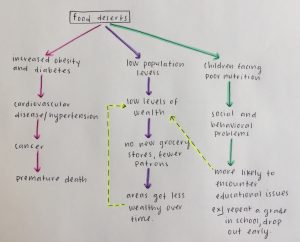

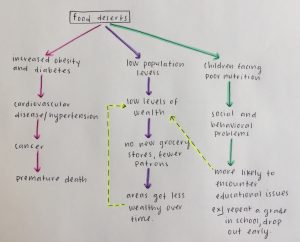

Food deserts are indicators of more than just socioeconomic injustice; they indicate public health and safety concerns for those living within their borders. Residents with a chronic lack of access to adequate food resources are shown to have higher rates of diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (Corapi). Families who cannot afford grocery stores will purchase food from the ever-available and affordable fast food restaurants, causing higher than usual rates of chronic illnesses to develop in the population. Along with medical bills that may exceed what a family is capable of paying, these chronic illnesses can cause diet-related cancers and even premature death. These severe consequences of living in a food desert represent the potential for a life expectancy far shorter than counterparts living near a grocery store. For example, adults diagnosed with diabetes can anticipate a life 15 years shorter than otherwise would have been allotted to them (Gallagher). In this case, consistent access to healthy food is truly a life or death situation.

Image 1: Diagram of the Impacts of Food Deserts by Barbara Lynn Weaver

Along with experiencing shorter than average life expectancy, families living within the bounds of food deserts are also subjected to decreasing wealth as time passes. By their very nature, food deserts are located in areas of low population and low income, but as time progresses, these two characteristics are exacerbated. As wealth abandons a neighborhood, businesses follow. This means that all too often, when new stores do open, they choose areas of relative wealth and prosperity. Without new businesses to bring economic attention to a neighborhood, that neighborhood will get less wealthy over time. This trend of decreasing wealth represents a positive feedback loop, in which low initial wealth causes even lower wealth to develop within a population. Additionally, food deserts have long term impacts on the economic success of the children raised within them. Children facing poor nutrition or chronic illness are statistically more susceptible to encountering social and behavioral problems in school (Child Hunger). Such problems can hinder educational advancements, causing children to incur administrative discipline or academic probation. Living in a food desert can stand between educational, and therefore economic, success or failure.

While causes of food deserts are systemic and their impacts often cyclical, many solutions are emerging that attempt to address multiple aspects of the harm caused by food deserts. A favorable program promising the eventual erasure of food deserts originates from the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The goal of the USDA’s Community Food Projects Competitive Grant Program is to increase access to local nutritious food by working with producers and consumers to promote independence, create long-term solutions, and construct programs that are beneficial for the whole community (CFP). Another solution is the opening of community-owned food cooperatives. In areas such as Greensboro, North Carolina, communities previously living within food deserts are given a sense of responsibility when shopping at their co-op grocery store because not only are they improving their own health, but they are also showing the value of communities that mobilize and make democratic decisions to benefit one another (Johnson). However, a point often overlooked is that increasing access to supermarkets and grocery stores does not necessarily change behavior. According to a pilot study in Philadelphia, members of a community in which access was expanded did not show an increase in the consumption of fruits or vegetables (Cummins). To further decrease the harm of food deserts, new initiatives need to be created to address the connected between community awareness and individual action.

Examining the causes, impacts, and solutions of resource insecurity found inside food deserts reveals the complexity of the problem and the importance of environmental justice. Historical events like redlining, which separate people of socioeconomic status, are inextricably linked to the creation of food deserts. Food deserts in turn lower the wealth and health of affected communities, leading to increasing public health concerns and propagating the cycle of poverty. Programs that acknowledge the issue, and bring it into the public sphere, are key to combating food deserts. Grocery stores alone cannot solve food deserts, and it is vital that the culture of fast food and convenience be examined in relation to socioeconomic disparities. Environmental justice, behavioral change, and exposure to adequate food have the potential to bring the development and expansion of food deserts under control when used in combination.

Works Cited

“Child Hunger in America.” Feeding America. Web. Fed 28, 2017. http://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/impact-of-hunger/child-hunger/?referrer=http://www.sustainableamerica.org/blog/what-is-food-insecurity/

Chinni, Dante. “The Socio-Economic Significance of Food Deserts.” PBS. June 29, 2011. Web. Feb. 29, 2017. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/the-socio-economic-significance-of-food-deserts/

“Community Food Projects (CFP) Competitive Grants Program.” National Institute of Food and Agriculture in partnership with the USDA. Web. Feb 27, 2017. https://nifa.usda.gov/funding-opportunity/community-food-projects-cfp-competitive-grants-program

Corapi, Sarah. “Why it takes more than a grocery store to eliminate a ‘food desert’” PBS. Feb 3, 2014. Web. Feb 27, 2017.http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/takes-grocery-store-eliminate-food-desert/

Cummins*, Steven, Ellen Flint, and Stephen A. Matthews. “New Neighborhood Grocery Store Increased Awareness Of Food Access But Did Not Alter Dietary Habits Or Obesity.”Health Affairs. N.p., 01 Feb. 2014. Web. 03 Mar. 2017. <http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/33/2/283.abstract>.

Elliot, Scott. “Tribal Communities Strive to Regain Food Sovereignty.” National Institute of Food and Agriculture in partnership with the USDA. Nov 17, 2015. Web. Mar 2, 2017. http://blogs.usda.gov/2015/11/17/tribal-communities-strive-to-regain-food-sovereignty/#more-61940

Gallagher, Mari. “The Chicago Food Desert Progress Report.” Mari Gallagher Research and Consulting Group. June 2009. Web. March 1, 2017. http://marigallagher.com/site_media/dynamic/project_files/ChicagoFoodDesProg2009.pdf

Hartman, Brian. “Food Insecurity: 1 in 6 Americans Struggles to Buy Food.” abc News. Sept. 8, 2011. Web. Feb. 28, 2017. http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/headlines/2011/09/food-insecurity-1-in-6-americans-struggles-to-buy-food/

Johnson, Cat. “New North Carolina Coop to Turn a Food Desert into a Food Oasis.”Shareable. 9 Feb. 2015. Web. 03 Mar. 2017. http://www.shareable.net/blog/new-north-carolina-coop-to-turn-a-food-desert-into-a-food-oasis

Morland, K., Wing, S., et al. “Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine. January 2002, vol. 22(1): p. 23-29. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11777675 (3/05/11)

Paula Dutko, Michele Ver Ploeg, Tracey Farrigan. “Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts.” Economic Research Service, USDA. Aug. 2012. Web. Feb. 27, 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/err140/30940_err140.pdf

Will Michaels, Frank Stasio. “Mapping Inequality: How Redlining is Still Affecting Inner Cities.” WUNC, North Carolina Public Radio. Jun 26, 2014. Web. Mar 2, 2017. http://wunc.org/post/mapping-inequality-how-redlining-still-affecting-inner-cities#stream/0

ir connection to the earth.

ir connection to the earth.