At a side event on oceans at COP 22 Dr. Kyle Van Houtan, Duke alum and current director of science at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, claimed, “the oceans are the lungs of the planet and the heart of the climate change”. While this seems like a bold statement especially somewhere like the COP, if we consider the huge role that oceans play in all of our lives we see that the importance of oceans cannot be overstated. Oceans:

- cover 71% of the earth

- contain 96% of the living space on earth

- are home to 80% of earths living organisms

- provide the biggest source of wild or domestic protein in the world

- create almost half the oxygen we breathe

- carry 90% of world trade

- hold an estimated 80% of the worlds mineral resources

Despite the importance of oceans, until last year they had not received much attention within COP. Although they are often discussed indirectly in topics such as adaptation, mitigation, disaster displacement, fisheries and the blue economy, the Paris Agreement is the first of the UNFCCC agreements in which oceans have been acknowledged. Last year at COP 21, Oceans Inc. reported on the over 70 events dedicated to oceans documenting their increased prominence, and throughout COP 21 several countries lent support to the ‘Because the Ocean’ Declaration which aims to create a special report on oceans through the IPCC, continue this work at the UN Ocean SDG Conference in Fiji in June 2017, and elaborate on an ocean action plan under the UNFCCC.

Major Ways Ocean Affects Climate

Although so many ocean processes and events are crucial to climate health, the most critical phenomenon at this time are ocean warming, ocean acidification and deoxygenation.

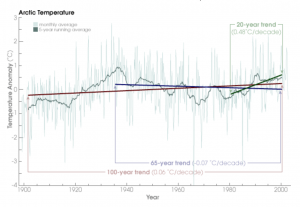

Ocean Warming

The oceans have shielded the world from rapid climate change by absorbing 1/3 of the carbon we produce and 93% of excess heat from global warming. The top 10 feet of the ocean hold as much heat as our entire atmosphere, but picking up this slack has not been without consequence and it is unclear how long the oceans can maintain this rate of absorption. As oceans warm, ice melts faster intensifying sea level rise and ocean circulation patterns slow down as there is less cold water being submerged which also affects upwelling. These are just a few of the possible negative implications of warming oceans, but the increased heat in the ocean has profound affects for a plethora of biological, chemical and physical ocean processes.

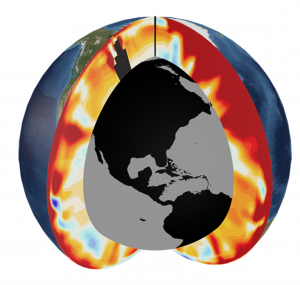

This image shows upper ocean warming over the past decade with red indicating a warming anomaly and blue indicating a cooling anomaly. (Source: Timo Bremer/LLNL)

Ocean Acidification

A related but separate issue facing the oceans is acidification. As the oceans take up an increasing amount of carbon, the chemical make-up of the water changes and the ocean moves from an alkaline environment to an acidic one. This can be fatally detrimental to much of the marine life that lives there particularly corals and organisms that have an exoskeleton or shell. Although these creatures are most directly affected, this will have implications for entire food webs, including for humans who rely on oceans as an important protein source. The potential harmful ramifications of acidification have been acknowledged by many around the world, including the Plymouth Marine Lab who made this short animation bringing to light the effects of acidification, and can already be seen at home in the US in the Arctic.

Deoxygenation

Another major effect climate change can have on oceans is the level of oxygen in the water. Warmer temperatures reduce oxygen solubility, but surface run off and ocean acidification can also play a role in deoxygenizing the ocean. Declining oxygen concentrations in the water will put stress on organisms that require oxygen to live as, according to National Geographic, low-oxygen areas have expanded by more than 1.7 million square miles in the last 50 years. If deoxygenation continues it will limit where species can live or if they will survive, which could negatively affect fisheries and the populations that rely on them.

Ocean art on display in the Green Zone at COP 22

Oceans at COP 22

While oceans perhaps weren’t as prominent at COP 22 as they were at COP21, there were several side events dedicated to awareness of oceans, and Prince Albert of Monaco and Princess Lalla of Morocco hosted, along with several other influential figures, Ocean Actions Day. During COP 22, the Ocean Action partners released the Strategic Action Roadmap on Oceans and Climate: 2016 to 2021, which provides comprehensive policy recommendations concerning oceans for the next five years. The roadmap specifically addresses the role of oceans in regulating climate, mitigation, adaptation, displacement, financing, and capacity development.

While these are great steps forward in the process of inclusion of oceans in the UNFCCC, as of now, there is still some discrepancy in who is giving attention to oceans. More than 2/3 of NDC’s include the ocean in some sense, but 14 countries that have coasts don’t include them. Many Annex 1 countries specifically, including the US, don’t address oceans even though they are coastal nations. Despite this, the momentum for addressing oceans in the climate negotiations continues to grow among states, NGO’s, academia and even within religious sectors. As Dr. Nigel Crawhill, representative of the Indigenous Peoples of Africa and the International Network of Buddhists, said in a panel on human abuse of the oceans, “sometimes we can become paralyzed by the complexity of the ocean problem, but in Buddhism the moment of enlightenment is only in the present, only now can we understand the capacity for ourselves to act.” Let us hope as we move forward as individuals, countries, and with each successive COP we continue to act on this important oceans agenda.

Sources:

Laffoley, D and Baxter J.M. Explaining Ocean Warming: Causes, Scale, Effects and Consequences. IUCN. September 2016.

AMAP Arctic Ocean Acidification Assessment: Summary for Policy-makers. This document presents the Executive Summary of the 2013 Arctic Ocean Acidification (AOA) Assessment. 2013.

Hot, Sour and Breathless- Ocean Under Stress. Report to UNFCCC in Durban, South Africa. 2010. http://usa.oceana.org/sites/default/files/ocean_under_stress_low_res.pdf

Welch, Craig. Oceans Are Losing Oxygen and Becoming More Hostile to Life. National Geographic. March 13, 2015.