A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of attending the Arctic Circle conference in Reykjavik, Iceland, an annual forum for governments, NGO’s, industry and scientists to converge on the most pressing Arctic issues facing the world. Although it feels far away for many of us, the melting of the Arctic may be one of the most defining events of our lives due to its far reaching consequences on rising sea level, rising ocean temperature, carbon release from melting permafrost, potential effects on global ocean circulation disrupting upwelling and fisheries and much more. As keynote speaker Ban Ki Moon warned, “when the Arctic suffers, the world feels the pain.”

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon stops by Arctic Circle Conference to address climate change in this delicate region

Few Arctic specific laws or policies currently exist as there was not much need to internationally govern what used to be a distant frozen mass, but as the ice melts and the Arctic opens up allowing an ever increasing number of actors access to it, there is a new need for these to be developed.

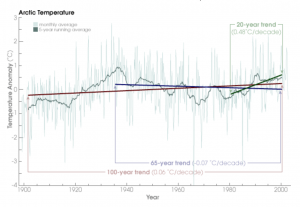

This process is occurring right now and repeatedly at Arctic Circle heads of state, NGOs and academics have referenced the Paris Agreement emphasizing how reducing global emissions to a 1.5 degree Celsius increase could help save the Arctic. The Arctic is warming at a much faster rate than most of the world, so a 2 degree global increase in warming could mean at least 5-6 degrees of warming in the Arctic, which would be devastating for the marine life and the ice.[1] Over the past 30 years alone, the Arctic has already warmed about 1.5 degrees C which is much more rapidly than the normal rate of melting, as highlighted in the NASA graphic below. This increased warming can be seen in every season of the year, not just summer, and NASA warns that this could have serious and far reaching affects not only for ice, ocean processes and sea level rise, but for land ice melt, coastal and island nations, as well as the chemical make-up of our atmosphere.[2]

Rates of Arctic temperature change over time (Source: NASA)

In light of these serious and well known potential consequences of warming in the Arctic and considering the attention given to the Paris Agreement at Arctic Circle, COP 22 (the self-proclaimed ‘COP of Action’) was a bit of a disappointment Arctic wise.

At Arctic Circle, Ban Ki-Moon called the Arctic ‘the ground zero for climate change’, yet at COP 22 there was very little mention of the Arctic whatsoever. This was especially disappointing after Arctic 21, a coalition of organizations focused on drawing attention to climate change in the Arctic, emerged last year in preparation for Paris.

Although this is disappointing, it was not altogether surprising. At the COP we see groups of likeminded countries coming together to form alliances over shared environmental conditions and values such as AOSIS or the Alliance of rainforest nations. The eight Arctic countries differ from these groups in that they are all fairly large wealthy developed countries, and for the most part, the Arctic is not their main priority at these meetings. This is particularly true for a country like the US, who have a plethora of other environmental goals and where the Arctic is a very small and physically removed portion of the country.

Eight Arctic Countries and land they have within the Arctic Circle (Source: Google)

With the emergence of an alliance of Arctic states being very unlikely at COP 22, where and when will the Arctic get its international representation? As of now, the Arctic Council is one of the only forum that gathers and addresses Arctic issues, but membership is limited to the eight Arctic countries and a few selected observers. For countries vying for Arctic Council observer status, a truly international climate meeting such as COP could have been an excellent doorway into addressing Arctic environmental issues at a broader scale.

In coming years as the ice melt continues to accelerate, it will be interesting to see if some of the smaller Arctic states not so heavily reliant on offshore oil, such as Iceland or Greenland, attempt to bring the Arctic into the spotlight at COP or try to merge Arctic interests with a group like AOSIS, or whether the issue will remain on the bench in the UNFCCC.

[1] A 5 Degree C Arctic in a 2 Degree C World: Challenges and Recommendations for Immediate Action. Briefing Paper for Arctic Science Ministerial. Sept 28, 2016.

[2] Ramanujan, Krishna. Dwindling Arctic Ice. NASA Earth Observatory. October 24, 2003. http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/ArcticIce/arctic_ice.php

Leave a Reply