The thing about exile is that it is far away.

Dostoevsky was sent to Semipalatinsk as a common soldier after his release from the Omsk fortress on March 2, 1854. The city is now called “Semey,” and it is now in Kazakhstan. Find Omsk in the map (under the “A” in “Russian Federation”) and slide down to the southeast until you see the second little red airplane. Like Omsk and other key locations on our journey, Semipalatinsk is on the Irtysh River.

Outside Dostoevsky circles, Semipalatinsk is best-known as a nuclear weapons testing facility, and the location of the first Soviet nuclear bomb test in 1949. For us Dostoevsky fanatics, though, its key attraction is its Dostoevsky Museum (https://www.fedordostoevsky.ru/museums/semipalatinsk/. In normal circumstances (whatever that means), this would put the town squarely on my itinerary. But not only do you need to veer wildly off the main route (whatever that is); you also have to get a visa to enter Kazakhstan. I am not proud of this, but I chickened out.

Instead, I decide to follow a love story.

This means a significant detour from the Trans-Siberian, also, I might say, not for the chicken-hearted, to the city of Novokuznetsk (formerly Stalinsk, and before that, Kuznetsk). A nice straight line would take me from Novosibirsk to Krasnoyarsk. But down to Novokuznetsk it is quite the zig-zag: a night train from Novosibirsk, a few hours in Novokuznetsk, and then back on the next night train to Novosibirsk. Seems arduous, but compared with Dostoevsky’s travel from Semipalatinsk to Kuznetsk by dusty horse carriage, it’s nothing.

Your train arrives at 6:00 am. Too early for breakfast. You’ve figured, OK, let’s get oriented and find the museum, then we can sit and have some coffee nearby for a couple of hours before our date with the muzeishchiki after the museum opens at 11:00.

There’s plenty of time, so why not walk? A half-hour on the hoof down a long, chilly, gray avenue makes it clear that Novokuznetsk is larger in reality than it seemed to be on the map. So you subject your cell phone to a vicious beating, and then set to learning about public transit. It’s not that hard, really.

Personally, I love transit systems that include conductors who take coins and can answer questions.

Eventually, after a very long spell of gazing out the window at the broad gray avenues of Novokuznetsk (a landscape ominously devoid of eating establishments), I am deposited near this church. Turn your back to it and look across the street:

Progress! Now for that coffee, a muffin, a dose of wi-fi, the New York Times on my iPad, a nice little dip into the WC….

HA HA HA HA HA HA HA HA!

There are some industrial facilities, a couple of storage lots, a bit of what could be called traffic at 7:30 a.m. (trucks, and and a couple of guys walking on the side of the road in weathered work clothes, carrying what appear to be lunch bags). A car or two. The barking of invisible dogs.

It dawns on me that there will not be coffee, or food. Nor will there be even a place to sit down, for it is muddy on Dostoevsky Street. I try not to think about what I must look like to the natives, train-disheveled, bespectacled, bewildered, scowling at my cell phone.

One good thing; my (OK, all right, our) navigation is good:

Looks pretty closed up–after all, it is 8:00 on a Saturday morning. Three hours to opening. I could kind of lean on the wall for a couple of those hours, I guess. Or do a Dmitry Karamazov.

I choose the latter. Right about where you see my big-city gray bag hanging on the palings, I make my move. A person of my age and dignity level really shouldn’t be clambering, but after some huffing and puffing and a couple of snags, it works. I’m in!

I dust myself off, neaten things up on my person, prowl the yard, and reconnoiter.

Footsteps…

A man walks through the gate. It was not locked.

It is Alexander Evgenievich. Alexander Evgenievich is the night guard. He does not shoot me. Instead he gently walks me into the (unlocked) door of the museum and introduces me to Olga, who is sitting quietly there behind the reception desk. He says to Olga, “feed her.”

Olga doesn’t seem to notice my bedraggled state, nor the fact that I have just broken into the Dostoevsky Museum. She takes me by the hand and walks me to her cozy house down the street. Oladi, fresh ham, vegetables, and hot tea magically appear. I have fallen down the rabbit hole. Time, which 15 minutes ago was a terrible burden, opens up infinite possibilities at the place Russia does best: the kitchen table.

Once calm has been restored, and we have shared life experiences, and I have savored this sublime breakfast, Olga walks me back to the Museum.

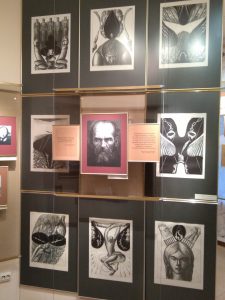

There she hands me over tenderly to the museum’s Deputy Director for Research Elena Dmitrievna Truk han, who takes me through a couple of special exhibits in the main building. One of these displays artifacts and photographs of theatrical productions of Dostoevsky’s work done here by visiting directors. I am lucky to catch the exhibit, which is to be taken down TODAY. Even better, I meet the photographer, Vladimir Semyonovich Pilipenko, a kind and very alert observer who has traveled all over Russia taking pictures. He’s not about to stop today. Indeed, Vladimir Semyonovich’s photos will soon appear in a report about our day together with Elena Dmitrievna at the museum. http://dom-dostoevskogo.ru/novosti/vizit-prezidenta-mezhdunarodnogo-obshhestva-dostoevskogo.html

han, who takes me through a couple of special exhibits in the main building. One of these displays artifacts and photographs of theatrical productions of Dostoevsky’s work done here by visiting directors. I am lucky to catch the exhibit, which is to be taken down TODAY. Even better, I meet the photographer, Vladimir Semyonovich Pilipenko, a kind and very alert observer who has traveled all over Russia taking pictures. He’s not about to stop today. Indeed, Vladimir Semyonovich’s photos will soon appear in a report about our day together with Elena Dmitrievna at the museum. http://dom-dostoevskogo.ru/novosti/vizit-prezidenta-mezhdunarodnogo-obshhestva-dostoevskogo.html

The other exhibit is a charming collection of children’s art inspired by the great children’s writer and poet Kornei Chukovsky.

The children have done collages and paper sculptures of Chukovsky characters. Here, as elsewhere on my travels, I’m deeply impressed with the Russian emphasis on arts education, and with the ways museums are reaching out to children, not just as places where they can learn about famous people, places and events, but where they can interact with history and literature, and, importantly, create art themselves.

Yes, science is important. Art is equally important, and you need it for your soul.

Dostoevsky made three trips to (pre Novo-) Kuznetsk, spending a total of 22 days here, all in pursuit, and finally conquest, of Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, whom he married in Kuznetsk in February of 1857. He had met her previously in Semipalatinsk, before her husband was transferred here. Then her husband died here….

Dostoevsky made three trips to (pre Novo-) Kuznetsk, spending a total of 22 days here, all in pursuit, and finally conquest, of Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, whom he married in Kuznetsk in February of 1857. He had met her previously in Semipalatinsk, before her husband was transferred here. Then her husband died here….

1st visit: 2 days in June 1856: during this first visit to Kuznetsk, Dostoevsky learned that he had a rival for her hand (Nikolai Vergunov);

2nd visit: 5 days in November 1856: having received his promotion to the rank of ensign (praporshchik)– he came to make an official proposal of marriage to Maria Dmitrevna;

3d visit: 15 days in January-February 1857: during this visit he married Maria Dmitrievna in the Odigitrievskaya Church, and spent the first days of his married life before returning with her and her son to Semipalatinsk.

Just down Dostoevsky Street from the museum’s main building, you can visit the house of the tailor Dmitriev, where Maria and her first husband Alexander Isaev rented a room. Wonder what she would have thought if she could have known her house was going to be on Dostoevsky Street? Wonder if anyone thought of naming it Maria Dmitrievna Street?

After posing this question, I received a fascinating answer from Elena Dmitrievna. Turns out, since the house technically did not belong to Dostoevsky, for years officials refused to allow a museum to be opened here. Only with the devoted efforts of local enthusiasts, with the support of the Dostoevsky Museum in Moscow, not to mention the sheer force of historical memory, did the museum finally open in 1980. The curious can read the full story here:

«Додумались» (в плохом смысле) чиновники, работающие в культуре. Очень долгое время они не давали открыть музей Достоевского в Новокузнецке, всячески препятствовали этому, называя дом не «Домиком Достоевского», как зовут сейчас его жители Новокузнецка, а Домом Исаевой, Домом портного Дмитриева. Их аргумент был «железным» и непробиваемым: «Не в каждом доме, где у писателя случился роман, надо открывать музеи».

Такой узкий краеведческий подход к событию (без культурного и литературного контекста) сделал своё грустное дело: открыть музей в Новокузнецке удалось только в 1980 году – то есть спустя 130 лет (!!!) после событий в Кузнецке. Вообще удивительно, как это удалось сделать! Если бы не помощь руководства музея Достоевского в Москве, если бы не местные энтузиасты-краеведы Новокузнецка, если бы не человеческая память, этого бы вовсе не случилось. И тогда еще одно место, связанное с жизнью Достоевского в Сибири, навсегда было утрачено.

Anyway, the house–the museum–is beautiful.

Elena takes me through the house. It is not an ordinary museum; rather it offers a kind of adventure, a  three-dimensional experience or even performance that loops in the story of Dostoevsky’s courtship of Maria with the larger story of the way his time with her influenced his writing. Novokuznetsk is a Dostoevsky city because of Maria’s story. Elena tells me this story, leading me from room to room. Vladimir Semyonovich is with us.

three-dimensional experience or even performance that loops in the story of Dostoevsky’s courtship of Maria with the larger story of the way his time with her influenced his writing. Novokuznetsk is a Dostoevsky city because of Maria’s story. Elena tells me this story, leading me from room to room. Vladimir Semyonovich is with us.

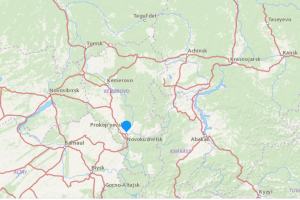

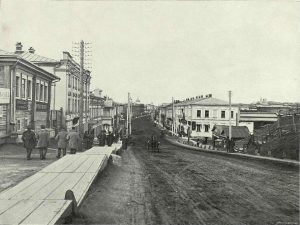

The diorama shows what Kuznetsk looked like when Maria lived here. The different rooms each offer a

part of her story, display documents and artifacts related to her relationship with Dostoevsky, and offer connections to his works. Here, for example, are copies of documents registering witnesses to their wedding ceremony, and Dostoevsky’s own scrawled lists of wedding expenses he had to cover. Elena is an active scholar herself, and works in archives to fill out the pictures relating to these years. For example, she found a document recording that Maria Dmitrievna had served as godmother of a baby (of the local citizen Petr Sapozhnikov) during her time in Kuznetsk. And, it turns out (as other scholars discovered), Maria Dmitrievna served as godmother to another child in that family AFTER her marriage. So the question stands; did Maria Dmitrievna and her husband (?!) make another visit to Kuznetsk?! The research continues.

The displays remind us of the ways Dostoevsky drew upon Maria Dmitrievna’s personality when creating characters such as Crime and Punishment‘s Katerina Ivanovna Marmeladova, and even Nastasia Filippovna of The Idiot. I take a quiet minute to ponder what it is, anyway, that writers do with life experience… Back in the museum, Dostoevsky’s famous meditation on the impossibilty of shedding the ego–written by his wife’s deathbed–“Masha is lying on the table,” is exhibited here on the wall.

.

.

One emerges from the museum full of impressions and thoughts about what life was like for Maria, and about why this person, time, and place were so formative for Dostoevsky’s life and works.

Elena then walks me around Novokuznetsk, to buildings that were standing during Dostoevsky’s time,

and to the town’s major attraction, the hilltop fortress, which in addition to its historical value, offers a beautiful view over Novokuznetsk:

We visit a newly renovated church (glimpsed in the photo above), and a newly built chapel by the train station.

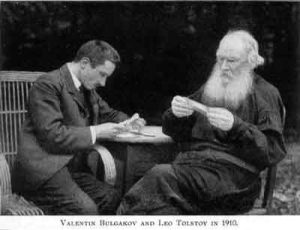

Tolstoy fans will appreciate the fact that Valentin Bulgakov, the writer’s secretary during the last year of his life, was from Kuznetsk. The name is familiar to anyone who saw the recent movie about Tolstoy’s last year, The Last Station, which draws on Bulgakov’s memoirs. On a longer visit I’d definitely visit the district school where Bulgakov’s father served as inspector–now a branch of the Novokuznetsk Ethnography Museum. Elena shows me the monument to him and Tolstoy: “Teacher and Student” (Учитель и ученик).

But let us not get distracted. Check out the Novokuznetsk Dostoevsky Museum’s website and many activities, including a virtual tour of an earlier iteration of the museum. And recently specialists in 3D graphics have produced a new virtual visit to the museum’s permanent exhibit, “A Guide to Novokuznetsk”: read about it here: http://www.dom-dostoevskogo.ru/novosti/3d-dostoevskij.html

Here’s the actual tour: http://vrkuzbass.ru/muz/nvkz/fmd/

And more! Check them out:

http://eng.md.spb.ru/dostoevskij/drugie_muzei_pisatelya/kuzneck/

https://www.fedordostoevsky.ru/museums/novokuznetsk/

http://dom-dostoevskogo.ru/muzei_dostoevsk/index.html

Take my word for it, Novokuznetsk has a lot to offer, and not just to Dostoevsky fanatics like me.

I am nurtured, mind, body and soul. But I cannot stay….there is a train to catch.

What I found extraordinary in the museum was the abundance of individual stories that it manages to tell, even as it presents the Gulag’s physical geography, its facts, dates, and statistics. Behind each fact and number lies a human tragedy, families torn apart, individuals tortured and murdered, children orphaned. One scary exhibit is a document (one of many) listing quotas of arrests that were assigned to each region. We know this; people were arrested not necessarily for any particular crime, but to meet NKVD quotas. During the height of the Terror, those administrators whose job it was to arrest, interrogate, and sentence people feared for their own lives. In one document a local official writes to Stalin asking for his quota to be raised by a few hundred or thousand–I don’t remember–in the hopes that his zeal in rooting out enemies will spare him from being arrested and shot himself. In Stalin’s handwriting, the official’s request is “approved.” And as a result, several hundred more people were arrested and executed–and probably, in due time, the desperate man who wrote this particular appeal.

What I found extraordinary in the museum was the abundance of individual stories that it manages to tell, even as it presents the Gulag’s physical geography, its facts, dates, and statistics. Behind each fact and number lies a human tragedy, families torn apart, individuals tortured and murdered, children orphaned. One scary exhibit is a document (one of many) listing quotas of arrests that were assigned to each region. We know this; people were arrested not necessarily for any particular crime, but to meet NKVD quotas. During the height of the Terror, those administrators whose job it was to arrest, interrogate, and sentence people feared for their own lives. In one document a local official writes to Stalin asking for his quota to be raised by a few hundred or thousand–I don’t remember–in the hopes that his zeal in rooting out enemies will spare him from being arrested and shot himself. In Stalin’s handwriting, the official’s request is “approved.” And as a result, several hundred more people were arrested and executed–and probably, in due time, the desperate man who wrote this particular appeal.

The Tom River

The Tom River

After wind, rain, icy dunkings and soakings, chills, and a cold, it is only natural that Chekhov would be grumpy upon his arrival in Tomsk. He liked the dinners at the Slavyansky Bazaar (BTW he used to eat at the Slavyansky Bazaar in Moscow too), but not much else, and basically holed up in his hotel room. Chekhov’s bad mood and the few words he said about Tomsk would prove formative to the city’s self-image forever after. Words carry weight whose impact can never be predicted.

After wind, rain, icy dunkings and soakings, chills, and a cold, it is only natural that Chekhov would be grumpy upon his arrival in Tomsk. He liked the dinners at the Slavyansky Bazaar (BTW he used to eat at the Slavyansky Bazaar in Moscow too), but not much else, and basically holed up in his hotel room. Chekhov’s bad mood and the few words he said about Tomsk would prove formative to the city’s self-image forever after. Words carry weight whose impact can never be predicted.

fare? Take a stroll near Shooters in Durham some random Saturday night at 2:00 am (uh, or whenever), and a whole throng of future elite, educated white-collar professionals might look and sound no better than these ditch-hugging Tomsk lushes. And, when you factor in the lurking corporate elements in this picture, my hometown Durham would be running neck and neck with something way worse than Chekhov’s momentarily glimpsed Tomsk.

fare? Take a stroll near Shooters in Durham some random Saturday night at 2:00 am (uh, or whenever), and a whole throng of future elite, educated white-collar professionals might look and sound no better than these ditch-hugging Tomsk lushes. And, when you factor in the lurking corporate elements in this picture, my hometown Durham would be running neck and neck with something way worse than Chekhov’s momentarily glimpsed Tomsk. the townspeople took up a collection and installed a statue by sculptor Leontii Usov on the river embankment, offering an inebriated local’s point of view on the transient visitor, entitled, “Anton Pavlovich Chekhov in Tomsk, seen by the eyes of a drunk peasant lying in a ditch and never having read the story “Kashtanka” (Антон Павлович Чехов в Томске глазами пьяного мужика, лежащего в канаве и не читавшего «Каштанку”. The peasant’s viewing position on the ground and his impaired vision have distorted the great writer’s body proportions. It is a nice touch that the Chekhov statue stands within

the townspeople took up a collection and installed a statue by sculptor Leontii Usov on the river embankment, offering an inebriated local’s point of view on the transient visitor, entitled, “Anton Pavlovich Chekhov in Tomsk, seen by the eyes of a drunk peasant lying in a ditch and never having read the story “Kashtanka” (Антон Павлович Чехов в Томске глазами пьяного мужика, лежащего в канаве и не читавшего «Каштанку”. The peasant’s viewing position on the ground and his impaired vision have distorted the great writer’s body proportions. It is a nice touch that the Chekhov statue stands within

to steal my Galereya Hotel keychain, (an act which, to my shame, I had considered). Just behind the Chekhov statue–which has become one of Tomsk’s most famous

to steal my Galereya Hotel keychain, (an act which, to my shame, I had considered). Just behind the Chekhov statue–which has become one of Tomsk’s most famous

,

,

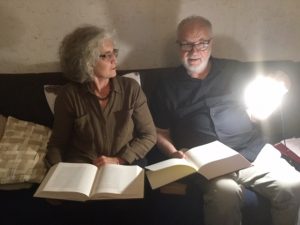

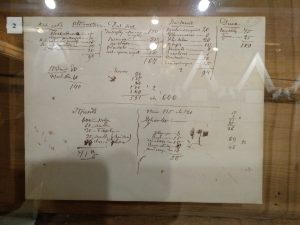

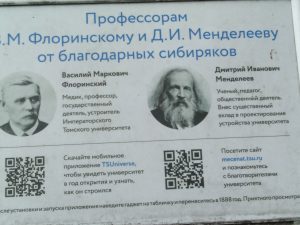

That the project is based in Tomsk sets it apart from most of the authoritative scholarly editions of Russian writers, which are generally done in Moscow and St. Petersburg by researchers based in central archives. Here two professors, Department Chair Vitaly Kiselev and Zhukovsky editor Olga Lebedeva, pose with some of the volumes. Spending time with them, and with Elena and Tanya, who share in their pride in this wonderful project, is starting to inspire me to work harder in my own scholarly explorations. You can take joy in this work. A supportive environment, with people who are happy when you succeed at something, can sustain you during those long hours spent alone in the basement of the library, or wherever you are with your headphones on, and it makes you a part of this dedicated scholarly family–which extends way beyond the walls of your cramped little box, and even the ever-more tightly-guarded borders of your country.

That the project is based in Tomsk sets it apart from most of the authoritative scholarly editions of Russian writers, which are generally done in Moscow and St. Petersburg by researchers based in central archives. Here two professors, Department Chair Vitaly Kiselev and Zhukovsky editor Olga Lebedeva, pose with some of the volumes. Spending time with them, and with Elena and Tanya, who share in their pride in this wonderful project, is starting to inspire me to work harder in my own scholarly explorations. You can take joy in this work. A supportive environment, with people who are happy when you succeed at something, can sustain you during those long hours spent alone in the basement of the library, or wherever you are with your headphones on, and it makes you a part of this dedicated scholarly family–which extends way beyond the walls of your cramped little box, and even the ever-more tightly-guarded borders of your country. One very charming and human thing is the cabinet here in the university courtyard, that students can leave books in that other students can pick up, if they need them. We have these in various neighborhoods in the US, usually for children. It’s nice to see it at the center of this very public place. And this may be the time to say that in my conversations with Russian colleagues during this trip, they almost universally express surprise at our system of paid higher education. Shouldn’t university education be free, they ask. Why should our young people, the future of the planet, be saddled with debt that some of them will spend their entire lives paying back, just to get an education that will enable them to become thoughtful, ethical citizens and fulfilled adults?

One very charming and human thing is the cabinet here in the university courtyard, that students can leave books in that other students can pick up, if they need them. We have these in various neighborhoods in the US, usually for children. It’s nice to see it at the center of this very public place. And this may be the time to say that in my conversations with Russian colleagues during this trip, they almost universally express surprise at our system of paid higher education. Shouldn’t university education be free, they ask. Why should our young people, the future of the planet, be saddled with debt that some of them will spend their entire lives paying back, just to get an education that will enable them to become thoughtful, ethical citizens and fulfilled adults?

,

,

Museum Director Victor Vaynerman kindly offers to shackle me using fetters matching those that Dostoevsky wore during his years in the Omsk Fortress. My smirk is not meant to be disrespectful; it expresses a nervous reaction to the prospect of being shackled here for the next four years. Prisoners wore cuffs under their shackles to protect their ankles from injury.

Museum Director Victor Vaynerman kindly offers to shackle me using fetters matching those that Dostoevsky wore during his years in the Omsk Fortress. My smirk is not meant to be disrespectful; it expresses a nervous reaction to the prospect of being shackled here for the next four years. Prisoners wore cuffs under their shackles to protect their ankles from injury.

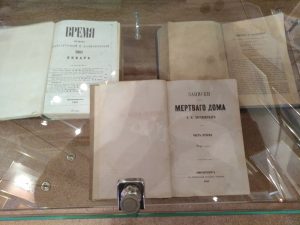

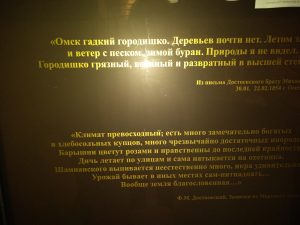

In the first, a letter Dostoevsky wrote to his brother Mikhail upon his release from the fortress in 1854. He pans Omsk:

In the first, a letter Dostoevsky wrote to his brother Mikhail upon his release from the fortress in 1854. He pans Omsk:

What I was picturing as a nice little chat with a dozen or so Dostoevsky enthusiasts turned out to be a sort of big Q&A in a lecture room with upwards of seventy students. When I walked in the room, accompanied by dean and faculty, all of them leapt to their feet. Which teleported me instantly back to Kazan, where I had learned about this custom in Russian classrooms and dreamed of experiencing it at Duke. No one in the room was crinkling fast-food wrappers or sipping at anything, either….What an alert group! We mostly talked about what attracts western readers to Dostoevsky (and Russian literature), about issues of language and translation, and about what (and whether) people read anything anymore. One student noted that it is common to see Omsk as the formative experience underlying all of his masterpieces. I am on board with that. Another handed me their required reading list for the English literature program, which requires them to read ever as much as our Duke students do–and remember, they are reading a lot of it in English…

What I was picturing as a nice little chat with a dozen or so Dostoevsky enthusiasts turned out to be a sort of big Q&A in a lecture room with upwards of seventy students. When I walked in the room, accompanied by dean and faculty, all of them leapt to their feet. Which teleported me instantly back to Kazan, where I had learned about this custom in Russian classrooms and dreamed of experiencing it at Duke. No one in the room was crinkling fast-food wrappers or sipping at anything, either….What an alert group! We mostly talked about what attracts western readers to Dostoevsky (and Russian literature), about issues of language and translation, and about what (and whether) people read anything anymore. One student noted that it is common to see Omsk as the formative experience underlying all of his masterpieces. I am on board with that. Another handed me their required reading list for the English literature program, which requires them to read ever as much as our Duke students do–and remember, they are reading a lot of it in English…

bizarre accident version– scornfully dismissed by my minder in Uglich–according to which little Dmitry was stricken by an epileptic fit and fell upon his dagger, slitting his own throat. In any case, the bell was arrested and, with some effort, for it was heavy, exiled here for a few centuries.

bizarre accident version– scornfully dismissed by my minder in Uglich–according to which little Dmitry was stricken by an epileptic fit and fell upon his dagger, slitting his own throat. In any case, the bell was arrested and, with some effort, for it was heavy, exiled here for a few centuries.

which hangs–as I have recently confirmed in the flesh–in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Before setting paint to canvas, Surikov visited this high cliff (now in Ermakovo Pole) overlooking the Irtysh River plain to survey the landscape. Here is how the scene looks to

which hangs–as I have recently confirmed in the flesh–in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Before setting paint to canvas, Surikov visited this high cliff (now in Ermakovo Pole) overlooking the Irtysh River plain to survey the landscape. Here is how the scene looks to day, I mean last week, and how it might have looked when Surikov (himself standing just behind you, or, if you are stuck in a blog, and on a real computer, not your #$%& device, to your left) planned the details of his painting. Many spirits fill the air here–not just those of Ermak and Surikov, but also those of the Tatars who roamed the land before them, and the spirits of us earthlings who have been lucky enough to visit, even though we have already left.

day, I mean last week, and how it might have looked when Surikov (himself standing just behind you, or, if you are stuck in a blog, and on a real computer, not your #$%& device, to your left) planned the details of his painting. Many spirits fill the air here–not just those of Ermak and Surikov, but also those of the Tatars who roamed the land before them, and the spirits of us earthlings who have been lucky enough to visit, even though we have already left.

Exiled to Siberia for dissenting with the Nikon reforms in the 17th century, Avvakum alit, among other places, in Tobolsk, along with his defiant flock, and held the old faith here with terrifying fervor. His church still stands (to your right, again, if you are using a normal grown-up device). My students grumble when I assign them Avvakum’s extraordinary autobiography, but I persevere. The mission of education sometimes entails plunging into very strange and distant territory (in time, space, and in the darkest depths of the human mind). Civilization tames these forces. Maintaining our feeble grasp on civilization, not to mention our personal convictions, is a continual struggle. In any case I have been excited to find, along my pathway through Siberia, reinforcement for my own passions in encounters with elite Siberian colleagues who have written articles and books on Avvakum. Of them later… meanwhile, and forever, the Old Believer Avvakum holds up his two fingers (foregrounded here) to this very day in permanent reproach to those who would turn Russia from the true path by insisting, among other things, that three fingers be used when crossing oneself. This astonishing little statue of Avvakum stands in Arkady Grigorievich’s study–which we will soon visit.

Exiled to Siberia for dissenting with the Nikon reforms in the 17th century, Avvakum alit, among other places, in Tobolsk, along with his defiant flock, and held the old faith here with terrifying fervor. His church still stands (to your right, again, if you are using a normal grown-up device). My students grumble when I assign them Avvakum’s extraordinary autobiography, but I persevere. The mission of education sometimes entails plunging into very strange and distant territory (in time, space, and in the darkest depths of the human mind). Civilization tames these forces. Maintaining our feeble grasp on civilization, not to mention our personal convictions, is a continual struggle. In any case I have been excited to find, along my pathway through Siberia, reinforcement for my own passions in encounters with elite Siberian colleagues who have written articles and books on Avvakum. Of them later… meanwhile, and forever, the Old Believer Avvakum holds up his two fingers (foregrounded here) to this very day in permanent reproach to those who would turn Russia from the true path by insisting, among other things, that three fingers be used when crossing oneself. This astonishing little statue of Avvakum stands in Arkady Grigorievich’s study–which we will soon visit.

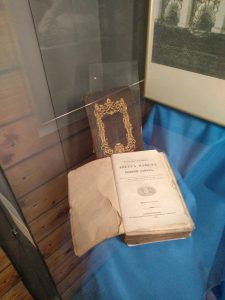

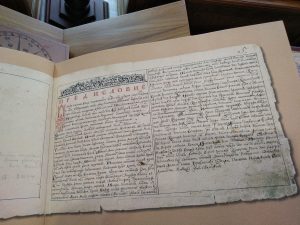

But that is not all. we splash through a couple of muddy alleyways, where you might hear a stray dog or two barking, and where an official-looking woman in uniform might run out at you, waving her arms and shouting something. And here stands an active place of incarceration, one that is in a considerably less attractive state than the renovated and cleaned prison museum complex that we have just visited. It is unmarked, dark, concealed behind clean things. I do not think it is on any tourist map. But there it stands. This is the one. Your mind fills with images of what it might have looked and felt like on that cold January day when Dostoevsky was brought here in fetters, not knowing what was to be his future fate. And then, what it would have been like for him when the Decembrist wives (who, as you learn from some other source) voluntarily followed their condemned husbands into indefinite Siberian exile) bribed the guards to let the come visit Dostoevsky and his Petrashevsky group companions, and gave them their copies of the Gospel (let me remind you, this very one), with a secret stash of money sewn into the binding.

But that is not all. we splash through a couple of muddy alleyways, where you might hear a stray dog or two barking, and where an official-looking woman in uniform might run out at you, waving her arms and shouting something. And here stands an active place of incarceration, one that is in a considerably less attractive state than the renovated and cleaned prison museum complex that we have just visited. It is unmarked, dark, concealed behind clean things. I do not think it is on any tourist map. But there it stands. This is the one. Your mind fills with images of what it might have looked and felt like on that cold January day when Dostoevsky was brought here in fetters, not knowing what was to be his future fate. And then, what it would have been like for him when the Decembrist wives (who, as you learn from some other source) voluntarily followed their condemned husbands into indefinite Siberian exile) bribed the guards to let the come visit Dostoevsky and his Petrashevsky group companions, and gave them their copies of the Gospel (let me remind you, this very one), with a secret stash of money sewn into the binding.