Where, indeed, if the prison you see in Tobolsk is one built after Dostoevsky passed through, can you find his traces there? And what was that about Chekhov’s Sakhalin Island? For this we need a guide. Our guide on this journey, proud city citizen Arkady Grigorievich Elfimov, will tie many of our story’s threads together. But first, we must take a detour.

Men of Action

Let us circle around to what is turning into a theme of our journey: the way human beings–especially mighty individuals–carve out a space for civilization, and make their mark on history, in the vast Siberian expanses. Arkady Grigorievich is one in a long line of such individuals. Another is the legendary Cossack ataman Ermak, who dominates the Tobolsk historyscape. After some drama with the resident Tatar population in the sixteenth century, Ermak conquered, let’s just say, Siberia, for Ivan the Terrible, and a city began to grow here.

Speaking of Ivan the Terrible, you may recall the story from Uglich about little prince Dmitry’s martyrdom. When the Uglich townspeople took revenge against Ivan the Terrible’s asassins (or innocent government employees, depending on who tells the tale), the tsar punished them by exiling their bell to Tobolsk. Here is its bell tower in the Tobolsk Kremlin:

Natalya, who escorted me around the Kremlin, adheres to the

bizarre accident version– scornfully dismissed by my minder in Uglich–according to which little Dmitry was stricken by an epileptic fit and fell upon his dagger, slitting his own throat. In any case, the bell was arrested and, with some effort, for it was heavy, exiled here for a few centuries.

As for Ermak, here he stands in the botanical garden and park, Ermakovo Pole, that Arkady Grigorievich (this blog post’s hero, I remind you) founded.

Here he is too in Vasily Surikov’s magnificent 1895 painting, “The Conquest of Siberia by Ermak” (1895), which hangs–as I have recently confirmed in the flesh–in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Before setting paint to canvas, Surikov visited this high cliff (now in Ermakovo Pole) overlooking the Irtysh River plain to survey the landscape. Here is how the scene looks to

which hangs–as I have recently confirmed in the flesh–in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Before setting paint to canvas, Surikov visited this high cliff (now in Ermakovo Pole) overlooking the Irtysh River plain to survey the landscape. Here is how the scene looks to day, I mean last week, and how it might have looked when Surikov (himself standing just behind you, or, if you are stuck in a blog, and on a real computer, not your #$%& device, to your left) planned the details of his painting. Many spirits fill the air here–not just those of Ermak and Surikov, but also those of the Tatars who roamed the land before them, and the spirits of us earthlings who have been lucky enough to visit, even though we have already left.

day, I mean last week, and how it might have looked when Surikov (himself standing just behind you, or, if you are stuck in a blog, and on a real computer, not your #$%& device, to your left) planned the details of his painting. Many spirits fill the air here–not just those of Ermak and Surikov, but also those of the Tatars who roamed the land before them, and the spirits of us earthlings who have been lucky enough to visit, even though we have already left.

Some of these spirits live in a young grove of lipa (linden or lime) trees being planted in Ermakovo Pole. Each tree bears a little tag with the name of the person who planted it. Here, among many others, is a tree planted by the Siberian writer Valentin Rasputin. To my surprise and delight, I stray upon the tree planted by Vladimir Nikolaevich Zakharov, another of our blog’s main heroes and recent past president of the International Dostoevsky Society.

And lest there be any suspense, I am granted the honor of planting one myself.

By the way, speaking of Surikov, himself a very strong person and painter of monstrous great canvases, I was able to visit his home a couple of days ago (or a week into the future, if you are trapped in blog space) in Krasnoyarsk. The house still stands. Squint and you’ll see his statue here, center left.

Inside the home are some of Surikov’s studies for the great canvases, photos, and personal objects, including his traveling painter’s case. Just for your reference, on our journey Krasnoyarsk comes after Tobolsk, Tiumen, Omsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk, and Novokuznetsk. Time and space are being crossed with great rapidity.

The Archpriest Avvkum

But back to Tobolsk, where other great men await their turn. Take the archpriest Avvakum, poster child for the great Russian schism and most famous of the Old Believers.  Exiled to Siberia for dissenting with the Nikon reforms in the 17th century, Avvakum alit, among other places, in Tobolsk, along with his defiant flock, and held the old faith here with terrifying fervor. His church still stands (to your right, again, if you are using a normal grown-up device). My students grumble when I assign them Avvakum’s extraordinary autobiography, but I persevere. The mission of education sometimes entails plunging into very strange and distant territory (in time, space, and in the darkest depths of the human mind). Civilization tames these forces. Maintaining our feeble grasp on civilization, not to mention our personal convictions, is a continual struggle. In any case I have been excited to find, along my pathway through Siberia, reinforcement for my own passions in encounters with elite Siberian colleagues who have written articles and books on Avvakum. Of them later… meanwhile, and forever, the Old Believer Avvakum holds up his two fingers (foregrounded here) to this very day in permanent reproach to those who would turn Russia from the true path by insisting, among other things, that three fingers be used when crossing oneself. This astonishing little statue of Avvakum stands in Arkady Grigorievich’s study–which we will soon visit.

Exiled to Siberia for dissenting with the Nikon reforms in the 17th century, Avvakum alit, among other places, in Tobolsk, along with his defiant flock, and held the old faith here with terrifying fervor. His church still stands (to your right, again, if you are using a normal grown-up device). My students grumble when I assign them Avvakum’s extraordinary autobiography, but I persevere. The mission of education sometimes entails plunging into very strange and distant territory (in time, space, and in the darkest depths of the human mind). Civilization tames these forces. Maintaining our feeble grasp on civilization, not to mention our personal convictions, is a continual struggle. In any case I have been excited to find, along my pathway through Siberia, reinforcement for my own passions in encounters with elite Siberian colleagues who have written articles and books on Avvakum. Of them later… meanwhile, and forever, the Old Believer Avvakum holds up his two fingers (foregrounded here) to this very day in permanent reproach to those who would turn Russia from the true path by insisting, among other things, that three fingers be used when crossing oneself. This astonishing little statue of Avvakum stands in Arkady Grigorievich’s study–which we will soon visit.

And while we’re on the subject of larger than life figures, let us not neglect the great Russian scientist Dmitry Mendeleev!! Pre-meds take note. He was born here in Tobolsk 1834. Who among us has not based our knowledge of chemistry (admittedly weaker in some of us than in others) on his famous periodic table of the elements? My visit to Ermakovo Pole fortuitously coincided with the dedication of a brand-new monument to Mendeleev, erected here to celebrate this year’s 150th anniversary of the periodic table. Present for the ceremony was a throng of Russian academicians. Here Arkady Grigorievich dedicates the monument. Be patient; by the end of this post you will know him well.

The Last Tsar

Not so long ago we were in Ekaterinburg, where we saw the Church on the Blood built in memory of the last Romanovs, who were murdered there. Tobolsk plays its part in that grim drama. Nicholas II, Alexandra, their children, and their faithful retainers, were brought here from St. Petersburg during the revolutionary disturbances there–for their protection? confinement? punishment? control? It is not clear. They spent the last months of their life in a home here that has been quite recently renovated and, just last year, opened as a museum.

The Romanov Museum in Tobolsk is the last house where they lived that is still standing. The museum was planned, researched, organized, and opened with great care, and it needs to go on your list if you are coming to Tobolsk. It is located in the lower town (here seen from the Kremlin walls).

A diorama shows the configuration of the house and yard.

The museum staff and volunteers have assembled authentic items, photographs, and period furnishings to convey the feel of what it must have been life for the family to live here during this stormy period when (fortunately) they did not yet know their fate.

The muzeishchiki, including the director, a tall young priest, guard these facts, . The museum is tasteful, factual, respectful, devoid of hysterics, and devastating.

In the museum it would be easy to miss a small list, posted on a side wall, of the people who made the decision to assassinate the family. The top name on the list Lenin, then comes Sverdlov. I get a twitch, having just seen this corner in Tobolsk, where Sverdlov Street crosses Sverdlov Alley. Not to mention I have just spend 4 days in the city of Sverdlovsk, now (as before) Ekaterinburg, but still the oblast of Sverdlovsk. These names and places and people are mixing together in a disturbing way. And it is history, before your eyes, and muddled in your brain, as it can be when you visit a place and see a completely different landscape than what they saw during their time, but yet it is the same one, and you are a part of it.

![]()

Their domestic chapel was recreated, as were other rooms in the house, based on photographs taken during the Romanovs’ time here.

Above you see the last known photo of the Tsarevich Alexis, and, on the right, Nicholas II’s study.

I repeat, visit this museum.

But What about Chekhov, and What About Dostoevsky?

OK! Let us visit Arkady Grigorievich’s study. Former mayor of Tobolsk, current central force in the Tobolsk Revival Foundation, metsenat (your new word for the day: philanthropist), collector, patron of the arts, and publisher, Arkady is a man of action and a man of taste. He commissioned the monuments you see in this post, for example, and conjured up the botanical garden. What brought me to Tobolsk, though, is his activity as a publisher and proud citizen of Siberia. Here in his study you will see the full set of his almanac, Tobolsk and All of Siberia:

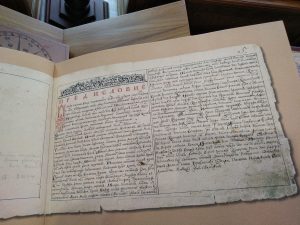

In addition to the almanac, we will recall, Arkady publishes special editions of great works associated with Siberia, among them the boxed set of Dostoevsky’s Gospel, which I saw at Vladimir Nikolaevich’s home in Moscow a couple of weeks ago, and duly reported on. There are too many such editions for us to share now, for we are in a tearing hurry, but just one will give a taste of the riches stored here. Behold a large manuscript atlas, reproduced on specially produced paper with scientifically recreated ink, full size, just as it looked when it was fresh, over three hundred years ago, and just lying here for you to look at, and even touch.

Speaking of publishing, Arkady has taken me to a meeting with representatives of the Tobolsk literature-journalism-and culture world (the Pedagogical Institute, the Library Museum on Red (or Beautiful) Square, the Romanov Museum, and of course Arkady Grigorievich), where I witness (and even am invited to participate in) a roundtable about the history of journalism in Tobolsk, and about plans to celebrate a key anniversary of the city’s major newspaper. I am impressed with the intellectual level of this conversation, and with the respect that everyone bears for their city’s (and Siberia’s) history and culture, not to mention its long history as a center of periodical publiction in Siberia (a land which, we could remind ourselves, once extended as far east as the eastern border of Alaska).

After the meeting, and a brief interview with me tacked on, we take a commemorative photo, and I get to sit on the Hero’s Bench. It turns out, that the event (I guess unsurprisingly) was reported in the Tobolsk press: https://tobolsk.ru/news/126/57027/

Carol, you are driving us nuts! What about Chekhov and Dostoevsky?

OK, all right.

Back in Arkady’s study, I feel we are hot on the trail. Indeed, a collection of commemorative medals hanging on the wall catches my eye. Among them leaps out one of the two great men whom I am pursuing.

Make a half turn, and there he is himself just below eye level.

Yes, Dostoevsky was, and is, in Tobolsk. He is here in Arkady’s office, at least two of him.

And what have we here? The Gospel box from Moscow! I mean, from Tobolsk, I mean IN Tobolsk. The Decembrist wives must be nearby….

We step out of the office. Arkady seats me in his car and takes me on a short drive.

We leave small things behind.

On a square near the Kremlin we see him. He is the same, but much bigger, taller and solider than you, above eye level, solid, stern, made to endure, made to provoke thoughts, made to slow you down and so that you can ponder important matters. Dostoevsky took this spot in 2010, with Arkady’s help, and he will stay here for a long, long time to come.

But that is not all. we splash through a couple of muddy alleyways, where you might hear a stray dog or two barking, and where an official-looking woman in uniform might run out at you, waving her arms and shouting something. And here stands an active place of incarceration, one that is in a considerably less attractive state than the renovated and cleaned prison museum complex that we have just visited. It is unmarked, dark, concealed behind clean things. I do not think it is on any tourist map. But there it stands. This is the one. Your mind fills with images of what it might have looked and felt like on that cold January day when Dostoevsky was brought here in fetters, not knowing what was to be his future fate. And then, what it would have been like for him when the Decembrist wives (who, as you learn from some other source) voluntarily followed their condemned husbands into indefinite Siberian exile) bribed the guards to let the come visit Dostoevsky and his Petrashevsky group companions, and gave them their copies of the Gospel (let me remind you, this very one), with a secret stash of money sewn into the binding.

But that is not all. we splash through a couple of muddy alleyways, where you might hear a stray dog or two barking, and where an official-looking woman in uniform might run out at you, waving her arms and shouting something. And here stands an active place of incarceration, one that is in a considerably less attractive state than the renovated and cleaned prison museum complex that we have just visited. It is unmarked, dark, concealed behind clean things. I do not think it is on any tourist map. But there it stands. This is the one. Your mind fills with images of what it might have looked and felt like on that cold January day when Dostoevsky was brought here in fetters, not knowing what was to be his future fate. And then, what it would have been like for him when the Decembrist wives (who, as you learn from some other source) voluntarily followed their condemned husbands into indefinite Siberian exile) bribed the guards to let the come visit Dostoevsky and his Petrashevsky group companions, and gave them their copies of the Gospel (let me remind you, this very one), with a secret stash of money sewn into the binding.

Pondering this, and overlaying the sight of this building onto what I know in my head about history and about Dostoevsky, and what has brewed inside for so many years from my reading of his works, reminds me that the words we read bear weight; they are not frivolous, or made up (and this applies to fiction as well as to history.

OK, but what about Chekhov?

What’s the matter with you–wasn’t this enough? And here I am almost ready to go home and think things over for a few years, before resuming my journey.

Time and patience, Tolstoy’s Kutuzov reminds us.

Stay tuned, and all your wishes will come true.

Leave a Reply