It is not Omsk’s fault that many of us know it only because Dostoevsky spent the darkest four years of his life here. And we discover, on our visit here, that there is a lot more to Omsk than the prison fortress (which in fact no longer even exists). We’ll get to that.

But first, let us track Dostoevsky’s steps. Sorry–it’s really clear in the photo I took. The regular line is to prison (heading right) and the dotted line is from. Omsk is kind of 1/4 of the way from the right. Tobolsk is up from there and left, where the angle is. Tobolsk would be on the hypotenuse, if oblique triangles had them.

Having passed through the transit prison at Tobolsk in early January 1859, where, you will recall, he received his Bible from the Decembrist wives Alexandra Muravyova, Natalya Fonvizina (left), and Polina Annenkova (right),

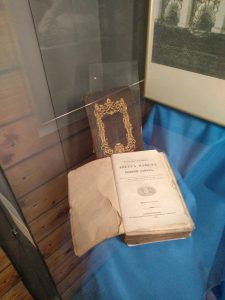

he arrived in Omsk on January 23. You should visit the Omsk Dostoevsky Literary Museum to get a sense of what life was like for him there. Along the way, you can learn about new generations of Siberian writers who, we’d like to think, studied him. This bible on display is a copy of the 1823 edition that Dostoevsky kept with him through his years in prison and for the rest of his life, and that Arkady Grigorievich published over 150 years later in Tobolsk.

Check out this extraordinary website on the subject: F. M. Dostoevsky: Anthology of Life and Works: https://www.fedordostoevsky.ru/biography/evangelie.

While you’re in there, please browse around. We are not in a hurry.

The Museum occupies the former headquarters of the Omsk Fortress commandants–poetic justice, I’d say.

Dostoevsky himself, of course, occupied grimmer quarters.

Upon his arrival in Omsk they did some paperwork, and then he had half his his head shaved and was issued his prison uniform. None of the photos of Dostoevsky date from this period, of course, so it’s worthwhile trying to picture what he looked like with his head shaven and wearing this coat and shackles.

Museum Director Victor Vaynerman kindly offers to shackle me using fetters matching those that Dostoevsky wore during his years in the Omsk Fortress. My smirk is not meant to be disrespectful; it expresses a nervous reaction to the prospect of being shackled here for the next four years. Prisoners wore cuffs under their shackles to protect their ankles from injury.

Museum Director Victor Vaynerman kindly offers to shackle me using fetters matching those that Dostoevsky wore during his years in the Omsk Fortress. My smirk is not meant to be disrespectful; it expresses a nervous reaction to the prospect of being shackled here for the next four years. Prisoners wore cuffs under their shackles to protect their ankles from injury.

At the museum, you get a chance to compare your height to Dostoevsky’s; he is a couple of inches taller than me.

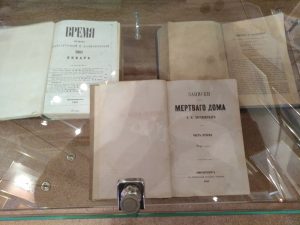

The museum displays first editions of Dostoevsky’s writing related to his time in Omsk, first and foremost, of course, his Notes from the House of the Dead, which if you haven’t read it, you must turn off your computer and go read it now. Spend a couple of weeks with the book, then come back and rejoin me here in Omsk.

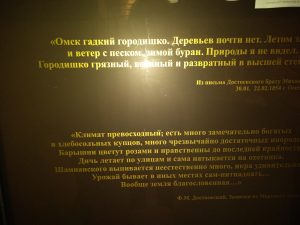

One of the museum’s walls features a clever display juxtaposing two quotes.  In the first, a letter Dostoevsky wrote to his brother Mikhail upon his release from the fortress in 1854. He pans Omsk:

In the first, a letter Dostoevsky wrote to his brother Mikhail upon his release from the fortress in 1854. He pans Omsk:

“Omsk is a disgusting excuse for a town. It is practically devoid of trees. In the summer––heat and dusty wind; in the winter, blizzards. I did not see nature. The town is filthy, military, and depraved to the highest degree.”

Омск гадкий городишка. Деревьев почти нет. Летом зной и ветер с песком, зимой буран. Природы я не видел. Городишка грязный, военный и развратный в высшей степени.

The other quote comes from the ecstatic ode to Siberia that opens Notes from the House of the Dead:

The climate is superb, wealthy and hospitable merchants abound, and there are many exceedingly well-off outsiders. The young ladies blossom like roses and are virtuous to the utmost degree. Wild game flies along the streets and heads straight for the hunter. An unnatural amount of champagne is drunk. The caviar is astonishing. In some locations the harvest is beyond belief.

Климат превосходный; есть много замечательно богатых и хлебосольных купцов; много чрезвычайно достаточных иногородцев. Барышни цветут розами и нравственны до последней крайности. Дичь летает по улицам и сама натыкается на охотника. Шампанского выпивается неестественно много. Икра удивительная. Урожай бывает в иных местах сам-пятнадцать…

It jumps out at me every time I read House of the Dead. Come on, now, isn’t there anything to say in the middle? Oh wait, this is Dostoevsky. And of course the book, and all his writing, seeks ways to find this abundance in the dark prison of our earthly existence.

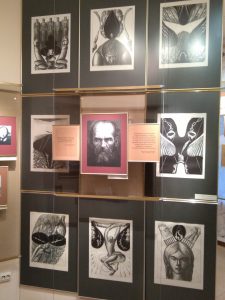

These illustrations to House of the Dead by Leonid Lamm should look familiar to those of us who spend time in Duke’s Nasher Art Museum, where we have a remarkable collection of this very series. Come on, Nasher, time to bring them up out of the basement!

During my visit the museum offered a special exhibit of miniatures (including “micro-miniatures”) relating to Dostoevsky’s work by a artist named A.I. Konenko. Miniature fanatics like me could spend a lot of time here, scrutinizing the icon in its case (1/4 inch high), portraits in shells, the print in the books and letters, and the bug with its fetters.

OK, enough playing around. Let’s go to prison.

The Omsk Prison Fortress

I am in fun company on this walk. Sergei teaches Russian literature, and, ahem, has written an entire book about the archpriest Avvakum. Students take note. Cool people like Avvakum. Nastya, Sergei’s former student, now works at this charming cultural center in Omsk, and she knows (and loves) everything there is to know (and love) about the town. Spend a couple of hours with her, and you will want to move here and stay in Omsk for the rest of your life.

The prison building itself and its walls fell into ruin (perhaps here, too, poetic justice), but the location is marked.

The site itself tells a story. You enter a parklike square, where a vertical row of logs (hinting at the prison wall) channels your attention toward a remarkable monument. Here along with you is Dostoevsky entering the prison, bearing his burden (crowned by a tiny 21-st-century flock of pigeons, or let’s call them doves, bearing some enigmatic message of hope). Note that Dostoevsky here stands at ground level. You do have to look up, but you can look him in the eye, though it feels intrusive.

You plunge into silence, pondering the nature of the man’s burden and its relationship to yours.

Then you proceed thoughtfully to the excavation site. Long ago, a big apartment building was constructed here, demolishing the prison’s brick and wood. Beyond a doubt, some grains of dust that Dostoevsky touched remain here, and maybe you even breathed them in, but for us, they are inscrutable.

And I allow myself, briefly, to wonder why I am here.

There’s an ad hoc feel to the House of the Dead illustrations posted at the excavation site, which only adds to their power.

As Dostoevsky’s narrator writes in House of the Dead, periodicallyprisoners were taken out of the prison stockade to the nearby church for services:

Walk a bit down the street from past the church, and you find yourself on a completely different kind of square, with a triumphal monument to the writer towering over it. Indeed,

Freedom, a new life, resurrection from the dead….what a glorious moment! Свобода, новая жизнь, воскресенье из мертвых… Экая славная минута!

exclaims the newly freed Dostoevsky’s narrator Goryanchikov at the end of the book. Did I already tell you to go read it?

Having taken a few moments to experience the moment to its fullest, you proceed on to the main part of the compound, which was separate from the prison area. Here the officers and administrators carried out those ostensibly banal functions that we don’t stop to ponder often enough, since they so closely resemble those that we carry out in our own lives, upon which our careers depend. Though of course some of the officials, say, the notoriously brutal Major Krivtsov, showed their sadistic side once they stepped out of their offices, that does not necessarily let the rest of us off the hook. Kenan Institute, do with this little outburst what you will.

I am told that this grating is original to Dostoevsky’s time. The door itself certainly gives off that feel too. He would have passed by many of these buildings when he was taken out to work. And the hospital that he describes so vividly is still standing, as well as the fortress headquarters.

What we really need to see, though, is the bank of the Irtysh River, for it has become a kind of focal point for our (and our writers’) meditations upon human existence. Most recently we spent time on its banks with Chekhov. And very shortly we will rejoin him there.

For now, in Omsk, Dostoevsky takes Raskolnikov to the riverbank in the epilogue of Crime and Punishment and directs his attention to the opposite shore, with its timeless Old Testament landscape of sheep and Kirgiz yurts. The scene in your mind will look quite different from what you see here in Omsk in the summer of 2019.

Everything here in the real world (whatever that is) feels up close. The buildings of the fortress square are right behind you, and beyond them the roar of traffic, dogs barking, the chatter of people strolling on the square.

Raskolnikov, who is on an alabaster kiln work detail, goes out to the shore by the work shed, sits on some logs piled there, and stares out onto the broad, desolate river.

He heard a song from the distant opposite shore. In the endless steppe, bathed in sunlight, could be seen the black spots of nomads’ yurts. Over there was freedom, and different people lived, completely different from those here, there it seemed that time itself had come to a halt, as though the age of Abraham and his flock had never passed. Raskolnikov sat there, looked out without moving, not shifting his gaze; his thoughts passed into dreams, into contemplation; he though of nothing, but a kind of longing disturbed and tormented him.

.С высокого берега открывалась широкая окрестность. С дальнего другого берега чуть слышно доносилась песня. Там, в облитой солнцем необозримой степи, чуть приметными точками чернелись кочевые юрты. Там была свобода и жили другие люди, совсем не похожие на здешних, там как бы самое время остановилось, точно не прошли еще века Авраама и стад его. Раскольников сидел, смотрел неподвижно, не отрываясь; мысль его переходила в грезы, в созерцание; он ни о чем не думал, но какая-то тоска волновала его и мучила.

Sonya appears suddenly beside him and stretches out her hand…and you can remember the rest.

Как это случилось, он и сам не знал, но вдруг что-то как бы подхватило его и как бы бросило к ее ногам. Он плакал и обнимал ее колени. В первое мгновение она ужасно испугалась, и всё лицо ее помертвело. Она вскочила с места и, задрожав, смотрела на него. Но тотчас же, в тот же миг она всё поняла. В глазах ее засветилось бесконечное счастье; она поняла, и для нее уже не было сомнения, что он любит, бесконечно любит ее и что настала же наконец эта минута…

Feel free to take a little break here.

All the information that helps situate us on the Irtysh river bank in Omsk does not come by chance. It is carefully preserved, researched, published, and taught by generations of muzeishchiki, scholars, citizens, and teachers. Among them are Sergei Demchenkov and Professor Oksana Issers, Dean of the Department of Philology and Media Communications at, ahem, **F.M. DOSTOEVSKY** Omsk State University, who invite me to an informal meeting with students.

What I was picturing as a nice little chat with a dozen or so Dostoevsky enthusiasts turned out to be a sort of big Q&A in a lecture room with upwards of seventy students. When I walked in the room, accompanied by dean and faculty, all of them leapt to their feet. Which teleported me instantly back to Kazan, where I had learned about this custom in Russian classrooms and dreamed of experiencing it at Duke. No one in the room was crinkling fast-food wrappers or sipping at anything, either….What an alert group! We mostly talked about what attracts western readers to Dostoevsky (and Russian literature), about issues of language and translation, and about what (and whether) people read anything anymore. One student noted that it is common to see Omsk as the formative experience underlying all of his masterpieces. I am on board with that. Another handed me their required reading list for the English literature program, which requires them to read ever as much as our Duke students do–and remember, they are reading a lot of it in English…

What I was picturing as a nice little chat with a dozen or so Dostoevsky enthusiasts turned out to be a sort of big Q&A in a lecture room with upwards of seventy students. When I walked in the room, accompanied by dean and faculty, all of them leapt to their feet. Which teleported me instantly back to Kazan, where I had learned about this custom in Russian classrooms and dreamed of experiencing it at Duke. No one in the room was crinkling fast-food wrappers or sipping at anything, either….What an alert group! We mostly talked about what attracts western readers to Dostoevsky (and Russian literature), about issues of language and translation, and about what (and whether) people read anything anymore. One student noted that it is common to see Omsk as the formative experience underlying all of his masterpieces. I am on board with that. Another handed me their required reading list for the English literature program, which requires them to read ever as much as our Duke students do–and remember, they are reading a lot of it in English…

After our conversation, they stood up and clapped! The dean told me that they are not forced to do so. And I had the unprecedented and exciting experience of being asked to be photographed with several clusters of students.

Then there were a couple of TV interviews (one for Omsk city, I think, and another for the student TV program).

Here are some of the news reports:

https://www.omskinform.ru/news/133712

https://www.omsk.kp.ru/online/news/3600105/

http://kvnews.ru/news-feed/v-omske-pobyvala-prezident-mezhdunarodnogo-obshchestva-dostoevskogo

https://omsk.sm-news.ru/omsk-posetila-amerikanskij-professor-izuchayushhij-dostoevskogo-4224/

https://russkiymir.ru/news/262052/

http://www.pulslive.com/news/puls-goroda/luchshe-chekhova-tolko-dostoevskiy.html

It all went to my head and I attempted to snap a selfie in front of the Omsk Department, call it, snapping board mirror.

The sad results of this attempt brought me down to earth.

Now Go Freshen Up

Omsk itself, as we started to say before we took our walk around Dostoevsky’s prison places, is well worth a visit. Its downtown, which has undergone active renovations, features quirky art, attractive little courtyards, and a goodly share of shout-outs to notable people. One such Omsk artist is the artist Mikhail Vrubel, who stands with back turned, mysteriously, to the viewer. Nearby we can visit a newly opened museum (seen here in pink) dedicated to white Russian civil war general Admiral Kolchak, who fought the Bolsheviks. Kolchak has enthusiastic fans here in the city, and we will soon visit Krasnoyars, the location of his ultimate defeat and execution. Also, looking like little cameos up on the drama theater facade, we have a welcome sighting of our old friends Chekhov and Tolstoy.

An early governor’s beloved, and mourned young wife Marinka, invites you to sit next to her on a bench and appreciate her short time on earth. We cannot be sad for her; we are happy to be alive.

At some point, you must go home, I mean to your hotel, which, though called the “Railroad Hotel,” took a 1/2 hour to reach by a predatory taxi driver, who approached you at the front side of the Omsk railway station and neglected to tell you that you could have exited the station at the back and just gone down a set of stairs to the entrance. 500 rubles. On the one hand, down the tubes, on the other, a valuable lesson. And really, who is to blame? You also learn, with a jab of regret, that your hotel is right next door to the DOSTOEVSKY HOSTEL,

Your regret is somewhat tempered by the presence of a cluster of thuggish-looking young men idling at the Dostoevsky Hostel’s entrance. Dusk (and, as it turns out, a raging thunderstorm, with rivers of mud, not to mention overindulgence in reading Dostoevsky) brings out fears that you normally keep securely repressed. Improbably, an angel in half-boots and an umbrella appears out of nowhere and gently leads you down the street in the dark. And you slink home to your safe little railroad hotel next door, where at least they know your name, and have taken your money.

Put transient things out of your mind. Dean Issers has arranged for me to meet a former Duma deputy from Omsk, who has made a practice of taking yearly CAR trips in Chekhov’s footsteps to the Island of Sakhalin. Tomorrow I will meet this man, Sergei Vorobchukov, and he will take me for a wild Chekhov drive.

Homework: sleep well.

Leave a Reply