Chance? Coincidence? Angels fluttering about? Or maybe some larger plan? This journey is taking me from Moscow to, as we note with increasing confidence, Sakhalin. At first I was timid about admitting this, suspecting I would chicken out en route and then have to deal with the shame of explaining to you why. But gradually Chekhov’s Island of Sakhalin, and the island of Sakhalin itself, has become not only a real plan but also a very strong theme, and a vehicle for the workings of fate. Let us return temporarily to Moscow to pick up the threads.

In Moscow, in July, before setting out, I spent a pleasant evening with Vladimir and Olga Zakharov. As has tended to happen at important times, we began with with my little electronic valet, who had decided not to put through any calls between us, necessitating some unnecessary circling through mud puddles. Even the combined efforts of the immediate past and the present presidents of the International Dostoevsky Society proved futile to bring it to heel.

So we put the device in time out and turned our thoughts to profound matters.

I recommend this strategy in all troublesome situations.

With some effort, Vladimir lifted a weighty box from a bookshelf and lowered it, with a gentle thud, onto a chair. The box was designed to look like a prison cell, complete with barred windows and a metal lock.

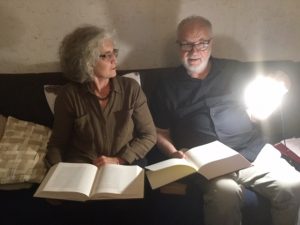

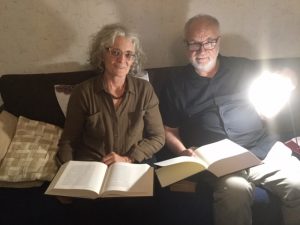

It is dark in the photo. It should look dark.

The doors open out, revealing another box, labeled “Евангелие” (Gospel), which itself opens out (I am not going to use the matryoshka metaphor here).

Inside are nestled two large volumes, one a facsimile edition of the Gospel (1923 edition) that, famously, the Decembrist wives (Muravyova, Annenkova and Fonvizina) gave to Dostoevsky during his stopover at the transit prison in Tobolsk. The other book contains a set of commentaries and supporting materials by scholars, including from Vladimipr’s team in Kаrelia, and of course Vladimir himself.

In addition to tracking references to the Gospel texts in Dostoevsky’s works, scholars examined the text using infrared technology to reveal marks that the writer had made in the margins, which are invisible to the naked eye.

I have been around the course a few times, but have never seen anything like this, in the quality of the actual physical thing, as well as of the scholarship within, a brilliant example of what our Russian colleagues call “tekstologia.”

For awhile, we fell out of ordinary time.

There is a story here, of course. It is not only the story of how Sonya Marmeladova read the story of Lazarus to Raskolnikov under the light of single candle; it is not only the story of how the great novels Dostoevsky wrote after his experience of hard-labor prison and exile emerged from his reading of this book; it is also the story of how this actual edition came into being. Vladimir tells me that this is just one of many projects relating to Siberian history and culture, sponsored by the Tobolsk Revival Foundation (фонд “Возрождение Тобольска”). He mentions that a recent project relates to Chekhov’s The Island of Sakhalin. I’m not sure how to take this information (can it really be true, even? Maybe my still-foreign Russian language has deceived me), nor how to envision such a thing in material form, if it does exist. And so it is determined that I will go to Tobolsk.

Nothing took Chekhov here. And Dostoevsky was brought against his will. He arrived in the town, then the capital of Siberia and a major transit point, January of 1850. Here convicts were sorted and distributed to their ultimate places of imprisonment and exile, and from here, Dostoevsky would be sent onward to Omsk–where we will take you in due time.

TOBOLSK

You may recall a story about what it was like to travel on the all-night train with the Vakhta to Tobolsk. About the stunning beauty of this town, and its rich history, I hope there will be time for me to emote later. But for now, after a quick couple of looks at the historic Tobolsk Kremlin (one out my window…)

we might stop in the prison museum opposite “Red [Beautiful] Square.” The prison was completed actually after Dostoevsky passed through Tobolsk, so these pictures probably belong in someone else’s blog. But in Siberia we must take note of the history of prison and exile, which rises before us at every stop.

I have to say, it’s an impressive complex that one could easily see as a public building of a completely different sort, a school for example. Among the rooms on display are a workshop, with an array of tools and tables, various rooms where prisoners of different faiths could worship, clean, well-maintained corridors, and what seemed to my unpracticed eye to be not completely unpleasant prison cells. There is a large, colorful chapel with a choir loft accessible to the prison corridor. Everything the heart could desire.

I had a crazy thought that this was not all that different from various dormitories I’ve been in during my lifetime. I’d like to live here! Peace and quiet, no unwanted telemarketing calls, no bills to pay, hours and hours for reading….With some force, I managed to picture what it would have been like here with the full sensual spectrum–not just the visual images of a neatly painted and varnished museum complex, but the sounds, feel, and smells, of a functioning prison in Imperial Russia, and yet more, during the Great Terror of the 1930s. Sounds: shouts and screams; feel: the lash, fetters, blows; and smells: recall that the cells were packed with unwashed and ill human bodies (or worse, harbored one isolated prisoner), and that the plumbing in its entirety consisted in a bucket in the corner. Would it be possible to make a museum that conveyed this complete picture?

History, here, there is. In the hallways are posted photos and displays with information about these more unsavory aspects of prison life, and, importantly, the stories of individual prisoners. Here as everyplace else I’ve visited, are given the dates of people’s lifetimes, ending in the year 1937, endless rows of them. And each person has a story.

Outside, you see individual prison exercise yards installed during the Soviet period, which allowed prisoners to be kept isolated from their fellow sufferers even during their short hour outside.

And on the river-side brick wall is posted a plaque to the memory of countless victims of the repressions, who were shot dead right here in this yard.

By the way, you can stay in a hostel in the prison complex, which I would have done if I had known about it:

All these thoughts about prison have distracted me from my quest. Dostoevsky did not see these sights that I am seeing; he passed here before this prison was built. What IS his place in the geography of Tobolsk? This I learn later, as will you.

Leave a Reply