There was a tree in Cairo whose name was “Kléber’s tree.” The tree was in the garden of the Shepheard’s Hotel, the presumed place of the French occupying army general Jean-Baptiste Kléber’s assassination in 1800. Then, there is a tree called “tree of the Virgin Mary” in al-Matariyya district, or simply the “Tree of the Virgin” as the Greeks call it; some believe that under this tree (or rather, under its ancient ancestor) Christ’s family found shade. There are so many tree-places in Cairo.

“Kléber’s tree.” Source: [Le Caire. Arbre dit “de Kléber”, dans le jardin de l’hôtel Shepheard’s] : [photographie négative], Gallica, BnF.

We have not yet discussed the ecology of Cairo. This city has always been the city of trees, gardens, lakes, and canals, with significant urban agriculture and horticulture. Successive waves of Muslim elites established pleasure spaces and organized forestry, plantations, including imported species of trees and flowers. The British occupiers also entertained large-scale greenery projects. Originally planned for public health, shade, and personal pleasure, the rich and mixed flora and fauna have been a remarkable feature of even twenty-first-century Cairo.

A lonely acacia in the 1870s in the Opera Square. Source: “[Photographies sur les transformations urbaines du Caire entre 1849 et 1946],” Gallica, BnF.

Khedive Ismail imported the banyan trees of India to his and his mother’s palaces in the 1860s. Today both Egyptians and foreigners are fascinated by these ecological invaders in central Cairo (around Garden city and Zamalek; some in Azbakiyya). Ismail was a lover of gardens and, apart from remaking the chic public garden of Azbakiyya, he planted a number of private and other public gardens. He thus also maintained an army of European and Egyptian gardeners in the 1860s-1870s. The shortage of wood in Egypt was also balanced by many types of imported timber trees.

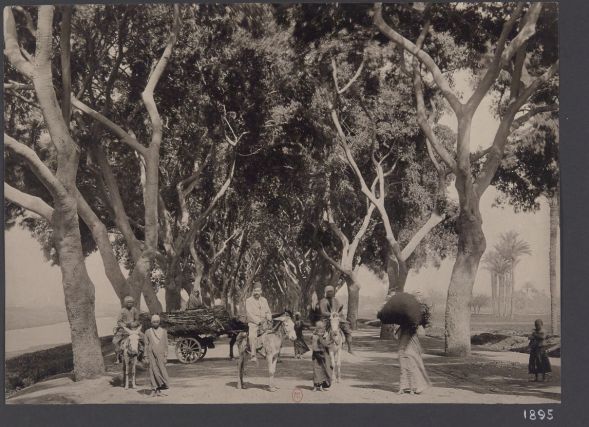

Trees in Gezira, 1895. Source: “[Photographies sur les transformations urbaines du Caire entre 1849 et 1946],” Gallica, BnF.

Yet the trees of Cairo are not only the elite trees of the pasha or capitalist flora. The date palms and acacia trees have been the native trees to Egypt and remained so. There is not much research on the transformation of various urban horticultural spaces in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The trees of Birkat al-Fil, detail. Source: “[Photographies sur les transformations urbaines du Caire entre 1849 et 1946],” Gallica, BnF.

Finally, while the rich and poor planted trees and gardens waves of urbanization have been also destroying these important health and psychological spaces. Have just a look in the avenue of Shubra !

The main avenue of Shubra, 1895 and 1947. Source: “[Photographies sur les transformations urbaines du Caire entre 1849 et 1946],” Gallica, BnF.

Bibliography:

Georg August Schweinfurth, Sur la flore des anciens jardins arabes d’Ėgypte (Imprimerie Nouvelle J. Barbier, 1888).

Edmond Pauty et al. « Les jardins du Caire à l’époque Ottomane. » Comité De Conservation Des Monuments De L’Art Arabe 1933, no. 37 (1940): 401-14.

Doris Behrens-Abouseif, Azbakiyya and its Environments from Azbak to Ismail, 1476–1879 (Cairo, 1985).

Alix Wilkinson, “Gardens in Cairo.” Garden History 38, no. 1 (2010): 124-49.

Adam Mestyan, “Power and Music in Cairo: Azbakiyya.” Urban History 40, no. 4 (2013): 681–704; idem, Arab Patriotism (PUP, 2017), Chapter Three.

Khaled Fahmy, In Quest of Justice: Islamic Law and Forensic Medicine in Modern Egypt. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), Chapter Three.

(A.M.)

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.