Diversifying the Romance Genre: “Disabled” Romance

By Abby Artmann (2016)

Since the publication of the first romance novel, Pamela, the tradition of the romance genre has been the portrayal of heterosexual, white couples (Fletcher, 2007). However, recent concerns about diversity within the romance genre have caused an increase in comments, blog posts, and studies on the representation of disabled romance within the genre. Since the inception of the romance genre in the 1970’s, the voices and stories of the disabled community have been left out. Through a limited study of online comments through blogs, studies conducted on disability and romance, and articles from authors and disabled readers, this paper argues that the disabled community became more vocal on the underrepresentation and misrepresentation of disabled romance over the last fifteen years and that these concerns are still a problem in the diversity of the romance genre today.

Many novels have been categorized and published as disabled romance within the past decade and a half. A list of books labeled as “disabled” on Goodreads contains 1,434 books. (Goodreads, 2016) However, starting in the early 2000’s, comments from romance readers through blog posts describe a dissatisfaction with these book’s representations of disability. Popular All About Romance blog posted a list in 1996 as an inclusive tribute to the disabled community’s participation in the romance genre. Despite the title, the list was disbanded and reorganized in 1999 into two sub lists, one was entitled: “Less than beautiful” and featured heroes or heroines that did not meet the standards of beauty for their time, and the other consisted of characters with specific physical or mental disabilities. Additionally, in a brief survey of fifty of the top romance blogs from Blogrank, only three blogs, six percent, mentioned disabled, in any capacity, in a major post. During this same time frame, a post from another blog, At the Back Fence in 2001 began to discuss this underrepresentation of disability within romance by pointing out that not all types of disabilities were being depicted within the genre, and that there are few heroines with disability. Most of the time, it is the hero who is disabled (LLB, 2001). A recent survey of seven hundred and eighty-three disabled romances concurs with her observation, showing over seventy-eight percent of the books depicting a hero with a disability. When momentum from these discussions about disabled romance began building, what was the response from the romance community? [ALA]

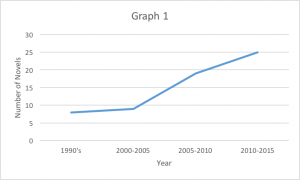

As the disabled community became more vocal during the late nineties and two thousands, there was a steady rise in the number of romances published under disabled. This observation was achieved through surveying the publication dates of sixty bestselling, disabled romances in five year increments for the past twenty years.

After the concerns around the representation of disability in romance were brought forward, graph 1 shows the response from authors and the romance genre and depicts a consistent increase in the amount of books that address this issue. However, do these books accurately depict the challenges facing the disabled community or are the voices of disabled romance readers still struggling to be recognized and heard?[ALA]

According to a study from the Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability in 2012, there is still a disconnect between author’s depictions of disability in romantic relationships, and the true experiences of people living with disabilities. Lead researcher on this study, Emily Baldys, describes how disabled characters in literature are manipulated within the story to become able-bodied through the healing power of heterosexual love. Baldys argues that these narratives strive to contain and control the disability and eventually “fix” it in order for a moving love story to thrive. She moves on from this point to state that these stories form an unconscious association between able-bodiedness and heterosexual love in the minds of romance readers. (Emily Baldys, 2012) Baldys is not alone in her conclusions on the way that disability is often portrayed. A woman suffering from a wheelchair-confining neuromuscular disorder depicts her own disappointment in the representation of disability in a recent post on popular romance blog, Dear Author. She describes herself as an avid romance reader and yet, is only able to recommend a handful of books that she feels encompass the genre of disabled romance. (Guest Reviewer, May 2012) Her report was followed up by a separate comment that describes disability as a “hole in the genre” (Gwen Hayes, 2012) Another post in 2013 from blog At the Back Fence, critiques the portrayal of disability within the romance genre by observing that authors still portray heroes or heroines with minor disabilities that are not reflective of the challenges faced by the disabled community. (Jackie C Horne 2013). Fantasy reviewer from RT book reviews, Natalie Luhrs, addresses this disparity in real life situations of disability and literary representations by stating that she would like to see more protagonists with a disability “more profound than an inconveniently placed birthmark or a limp”. She goes on to say that she would love to see a novel that studies the challenges that people with disabilities encounter while forming relationships and having enriching sex lives (Natalie Luhrs, 2012).[ALA]

Despite the progress in the volume of disabled romance stories, researcher Ria Cheyne concurs with Baldys’s conclusions on the disconnect between real life disability and literary representation of disability and states the the conversation has only just begun. In her article, Disability Studies Reads the Romance, Cheyne looks at Mary Balogh’s the Slightly series (published 2003-04) and, from the same author, the Simply series (published 2005-08). Her argument centers around how people conceptualize disability through literary characters and talks on how much potential the romance industry has to overturn damaging stereotypes surrounding disability. Cheyne points out that the romance industry, as one of the most popular literary genres, has a tremendous opportunity in the portrayal of disability and has the opportunity to present disabled characters in a powerful way that challenges negative attitudes and perceptions that surround disabilities. (Ria Cheyne, 2013) [ALA]

Cheyne’s study ushers in a different perspective on the power that literary representations have for progressive thinking. Her article describing the power that authors have in the ways they present characters highlights the importance of continuing to diversify the romance genre in the area of disability. With these studies, comments, reviews and perspectives in mind, the findings of this paper conclude that there a deficit between portrayals of disabled romance and real-life disabled romance was recognized in the early two thousands and that this disconnect and the overall representation of disabled romance remains as a problem in the diversification of the romance genre. [ALA]

Sources Cited

Natalie Luhrs, December 3, 2012, blog post, “Expanding the Boundaries of Romance”, Pretty Terrible, http://www.pretty-terrible.com/2012/12/03/expanding-the-boundaries-of-romance/

Emily M. Baldys, “Disabled Sexuality Incorporated: the compulsions of popular romance”, Journal of literary and cultural disabilities, 6.2 (July 2012): 125, accessed April 17, 2016, doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.lib.duke.edu/10.3828/jlcds.2012.12.

“Goodreads”, last modified 2016, https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/9459.SCARS_ARE_SEXY_Books_with_imperfect_disfigured_disabled_heroes

Lisa Fletcher, “Historical Romance Fiction: Heterosexuality and Performativity” (Farnham: Ashgate, 2007), 1-9.

Jackie C. Horne, “Critiquing the Portrayal of Disability in Romance.” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 6.2 (2012): 125–141

Ria Cheyne. “Disability Studies Reads the Romance.” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 7, no. 1 (2013): 37-52. https://muse.jhu.edu/ (accessed April 18, 2016).