The disagreement is not ultimately rooted in Scripture, but in how different people see Scripture functioning in the life of the Church

Recently I listened to a sermon that, in part, covered the topic of whether women can serve as elders and have pastoral roles with authority over men in the Church. The pastor, whom I have a great deal of r espect for and who is a brilliant preacher and teacher, concluded that Scripture–and thus God–do not allow women in these capacities. I did not agree with this part of the sermon at all. I used to reluctantly hold the same position, because the Christian tradition in which I was raised saw the Bible verses against women speaking or teaching in the Church and concluded that that was simply how God designed the relationship of the two genders to each other. I knew plenty of women who were brilliant gifted teachers and leaders, but if God did not want them to exercise those gifts in the capacity of Church leadership, who was I to argue with God. However, during my first year of seminary, I had my own Damascus Road experience on the relationship between women and men, authority and gender roles. I came to believe that while, speaking generally, women and men do complement each other, there is not a God-ordained hierarchy in place that has husbands or men by way of their genders exercising authority or power over their wives or women, whether in the Church, marriage, or anywhere else; women and men are “co-regents” with equal authority called to be caretakers of the earth. And I am someone who does believe that Scripture is sacred and that God exercises God’s authority in great part through it; I came to my beliefs on this through wrestling with Scripture. (For a quick overview of how I approach Scripture and doing theology, click here.)

espect for and who is a brilliant preacher and teacher, concluded that Scripture–and thus God–do not allow women in these capacities. I did not agree with this part of the sermon at all. I used to reluctantly hold the same position, because the Christian tradition in which I was raised saw the Bible verses against women speaking or teaching in the Church and concluded that that was simply how God designed the relationship of the two genders to each other. I knew plenty of women who were brilliant gifted teachers and leaders, but if God did not want them to exercise those gifts in the capacity of Church leadership, who was I to argue with God. However, during my first year of seminary, I had my own Damascus Road experience on the relationship between women and men, authority and gender roles. I came to believe that while, speaking generally, women and men do complement each other, there is not a God-ordained hierarchy in place that has husbands or men by way of their genders exercising authority or power over their wives or women, whether in the Church, marriage, or anywhere else; women and men are “co-regents” with equal authority called to be caretakers of the earth. And I am someone who does believe that Scripture is sacred and that God exercises God’s authority in great part through it; I came to my beliefs on this through wrestling with Scripture. (For a quick overview of how I approach Scripture and doing theology, click here.)

The question that gets asked all of the time when Christians strongly disagree with one another on a theological issue arises here as well: how can two Christians read the same Scripture, the same words inked onto the page, and come to two completely opposite conclusions? In the case of women in pastoral leadership roles and the way Protestants argue about it (and, frankly, many other divisive issues as well), the difference is not in whether they are reading the same Bible, but rather in the often-unnoticed realm of how each actually believes Scripture functions and is appropriated in the life of the Church. Though it would arguably take volumes and volumes of books to thoroughly explain the difference, there is one way basic way to show the differences that captures a lot of what is likely happening. The place I saw this explicated well was in New Testament professor, Craig C. Hill’s book on reading Revelation, called In God’s Time: The Bible and the Future (Eerdmans, 2002, pp. 22-29). As I found them helpful, I will apply Hill’s categories and verbiage to the women-in-pastoral-leadership issue to show the difference.

In essence, many Christians that argue for what is called “male headship” over women use what Hill calls a “conforming” approach to Scripture, whereas some Christians who argue that there is no gender hierarchy in God’s economy have a “modeling” approach instead. Though this is admittedly a gross over-generalization, the “conforming” approach believes that the way Scripture works in the Church is that the Church is to read it, try to understand what it is saying, and then do/conform to what it says. As the Christian cliché goes, it is seen as life’s instruction manual for how to live, given by God. Or some may see it as like a rule book or a constitution. If the Scripture says you should not murder, you do not murder. If it says women should be silent in church and not have authority over a man, then it is saying so as a propositional truth about how church life should be structured. So you go with that no matter what the surrounding culture’s ethos or circumstances may be. One guiding principle that those with the conforming approach put forth is that in Scripture there are both timeless teachings and principles that exist alongside those that are culturally bounded and only meant for the time that the texts were first written; a key reading skill in this perspective is to learn to recognize the difference.

The problem with the conforming approach when examined is that it does not really work in the particulars. It can be difficult to simply embody the statement, “I just do what the Bible says,” because as Hill notes Scripture contains multiple perspectives within it on all sorts of topics (he gives the example of the Gospel of Mark dealing with the question of handwashing and concluding that all foods are clean for Christ-followers, whereas Matthew–written from a Jewish-Christian persuasion–concludes that such Christians do not have to worry about handwashing but are not free to abandon Jewish dietary restrictions, cf. Matt 15.1-20 and Mark 7.1-23 [p. 24]). What ends up happening then is that people take the verses they tend to already agree with and use those to explain away the ones they do not (everyone does this in any approach to reading Scripture; the key is to be aware that you do so and understand why). And the idea that there are universal principles embedded in Scripture that can clearly be separated from culturally-conditioned and culturally-bounded ones is not actually a way of reading Scripture that the Bible itself expresses or suggests. It does not say in parts, “What I am about to say here is for all places forever, but over here what I say is just for now.” For those arguing against women in pastoral teaching roles over men, they point to 1 Tim 2.9 where it says women should not have their hair braided or wear expensive clothes, gold, or pearls and say that relates to a cultural situation that is bounded to that time and a timeless principle should be looked at there. However, two verses later the text says women should not speak in church or have authority over a man and they say that is timeless and universal. The verses are right by each other and there are no marking transitions to suggest one is going from cultural to universal principles and situations and yet that is the leap these contemporary readers make. I would argue instead that it is not that there are universal teachings and then cultural ones that themselves have some universal principle embedded in them; it is ALL cultural.

The approach to reading and appropriating Scripture that I would argue is more faithful is one of “modeling.” Rather than coming to the text as if it were a timeless rule book or a script to be conformed to over and over, the modeling view sees Scripture as telling the story of God and his relationship to people showing the shape and character of God through time, at various points of revelation, and in various differing circumstances leading up to God’s self-revelation in the incarnation of Christ. Oddly, I have found that the easiest way to explain what the model approach means is from a quote that I heard in….a teen movie years ago (an Amanda Bynes one actually; OK, you can stop laughing now). The main character’s dad says to her, “Following in someone’s footsteps does not mean trying to relive their life; it means trying to be the kind of person they were.” The conforming approach often seems to be about trying to relive the first-century Church’s life, idealizing it, even though a majority of the letters in the NT exist as criticisms and corrections of those communities. The problem with is we are not in a 1st-century context with 1st-century assumptions trying to deal with 1st-century situations. The Bible is not a script to be enacted. Instead, the modeling approach suggests that in reading Scripture with all of its interesting, puzzling, and differing perspectives, we look for the kind of God shown there and the kind of human community God has called people into. For instances, in many places the Bible assumes slavery as a part of the world and in some contexts talks about better ways of living with it. However, to see such verses and to conclude that the God of Scripture is OK with slavery is to miss the overall character of God conveyed in the text and the trajectory of the overarching story toward freedom. This is the same with the way women are portrayed in Scripture.

Rather than reinvent the wheel, I will try to further my point about the equality of women and men in authority bestowed upon them by God by concluding here with a letter I wrote several years ago to a couple of friends. They did not believe that women should be ordained as pastors and suggested my arguing against them was an example of me going along with secular culture rather than Scripture; they were using arguments made by pastors like John Piper and Mark Driscoll. Here is my response, which in some places contains redundancies with what I wrote above, but should show an example of how the modeling perspective works on the women-in-church-leadership issue:

It is important to try to discern what God has called humanity to rather than making arguments rooted in secular ideology or what is considered acceptable in contemporary culture (Since I believe that sometime at the beginning of humanity something went wrong and God’s good creation got warped, I am generally leery of arguments that go from “is” to “ought,” meaning because things are a certain way means they ought to be that way.) As Christian people, I think the “logic” that we should operate under is one that is determined and constituted by the narrative of the God of Israel, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, as told in Scripture and passed down and interpreted by the Church. While this is not to say that secular perspectives or those brought to us by other faiths are not helpful in introducing questions and circumstances that we might not otherwise see or pay attention to, even in those things we have to weigh such encounters and questions against the God of Israel as revealed in Scripture and interpreted by the Israel and the Church (I know I am being a bit redundant, but I just want to be as clear as possible).

So, with all of that said, I agree that as Christians we need to ask what God desires for our lives and how we live them. The problem I have is that I do not think that what is reflected in complementarianism (the belief that women and men are different, the differences complement each other, AND men have authority over women in teaching and pastoring contexts in the Church and in marriage) and the perspectives of folks like Moore, Piper, Driscoll, and Grudem, is what God ultimately desires for humanity and I will argue that with Scripture as it gets read by the Church. I will say upfront that I do not think that everyone that is a complementarian is one because they are somehow a sexist, hate women, etc. (Of course there are those types of people out there, but most complementarians I know are not such people. They are people that love their spouses and really want to do what is right by God and be faithful to what God has said). I will also concede that the burden of proof in such a discussion is on folks with my perspective since the interpretations that the Church has largely had throughout its history have affirmed more patriarchal perspectives. The Church has been wrong about plenty of things in its history (think endorsements of slavery or using state power to execute people for theological heresy), so longevity of a held belief does not in itself make it right. In my mind, this simply means it needs to be taken seriously and disproved rather than assumed up front carte blanche to be wrong.

In dealing with this question, I think it is important to start by considering how Scripture actually works to understand or determine anything for Christians. It is not as simple as simply finding one, two, or several passages that say something and then simply applying such things literally. The Church has never operated this way with Scripture. People that think they just do what the Bible says in some literalistic sense are actually not doing what they think they are doing. For instance, Scripture does not specifically condemn slavery, yet most Christians in the world would say that the trajectory of the message of Scripture and the God to whom Scripture points is against human slavery. Or when people see verses about how women should wear headcoverings or not braid their hair or wear jewelry, most Christians dismiss such texts as cultural outworkings of some “universal” truths (Ironically these passages occur right next to passages telling women to be silent in churches and yet some folks say the jewelry and braid admonitions are cultural and the silence thing is a universal event though the text does not suggest any such transition; all the things happening there are occurring within a culture. So, that said, yes, there are verses that talk about women being silent or being submissive to their husbands and how Onesimus should return to his slavemaster in Philemon, but that does not mean that Scripture is meant to function in taking such particular things out of the context of its larger message about God and what God desires for us.

I think that the lens through which to interpret the “complementarian” question is the lens of Jesus, who he was, and what he accomplished. My basic argument is two-fold and fits ultimately under the one Jesus.

First, Gal 3.28 says, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” I would argue this passage does not eliminate differences in Christ as much as the differences become relative now to Christ. In other words, such difference become secondary to the ultimately unity and oneness is Jesus. Now, if you look at the particulars listed in this verse and consider how Scripture and its trajectory have played out in the history of the Church, you will see it pointing in the direction of forms of equality of worth and power. In Christ, there are still Jews and Gentiles, but if we take Romans seriously, Jewish Christians do not have authority over Gentile Christians and do not have a hierarchical role above them, though they still have unique things they have done and do as Jews. And with “slave nor free” most of us would argue that in Christ that pattern has been obliterated or should be (While Philemon does not condemn the institution of slavery and seems to endorse it on one level, there are ultimately subversive suggestions in it that hold a gospel logic that goes against slavery). That leaves male and female. If Christ has brought Jew and Gentile together on equal footing before God without one of them having power or authority over the other and yet still remaining Jew and Gentile, and if God has obliterated slavery in the Gospel of Jesus, why would one still argue that men by nature of having penises and certain ratios of brain chemicals get to have power and authority over women/their wives?

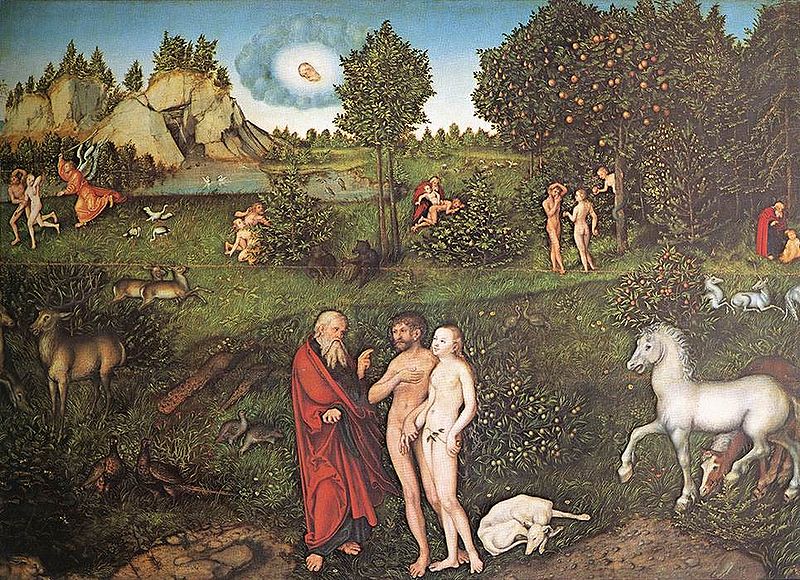

Second, if you want a scriptural justification for reading the “male and female” part in Galatians in an egalitarian way, then I would suggest that one considers the Genesis Fall story. Basically, according to the Adam and Eve narrative, wife/woman’s subservience to her husband/man is the result of a curse. Because of the whole forbidden fruit thing, God says, “To the woman he said,‘I will greatly increase your pangs in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children, yet your desire shall be for your husband,and he shall rule over you.’” If God declares such a curse as the result of the fruit incident, that means that prior to the incident the woman’s husband was not meant to rule over her; the woman being ruled by the man is the result of a curse, not the original edenic creation. (When the OT calls Eve a “helpmate” the Hebrew word used there appears 20 times in the OT. Of the 20 times, 18 of those refer to God as a “helpmate” to particular people. I say that because the word helpmate in Hebrew as it is used about Eve does not carry a natural connotation of subservience or “power over.” It simply means someone to come alongside of and help as God often does.) Again, if women are subservient to men as a result of the curse of the Fall, then what did Christ come to do? He came to reverse the effects of the Fall and bring things back into order with what God originally intended. Ergo, the curse of Adam’s sin–which includes the curse placed on Eve–is broken in the new Adam, who is Jesus. Men and women are co-regents in Christ over the world as was God’s original intention. Why Christians would want to continue upholding a curse after Christ death has broken such a thing is puzzling to me.

I get that my reading is newer in the long history of the Church, but that does not make it automatically wrong. I think the horrible abuse that women have endured at the hands of men (and, of course, I know that women are equally sinners just like men) have brought the Church–at least the Church in some parts of the world–to take a look at the living breathing Word of God to see if maybe we have been missing something. And just like we realized that with slavery, I believe we are starting to realize that with women and men and how they relate to each other in marriage and in other context.

So, yes, I think John Piper and folks in his camp are wrong, though I, of course, consider them brothers in Christ.