In August 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), a landmark piece of legislation designed primarily to help the United States decarbonize while reviving domestic manufacturing. One of the most important novel programs in the IRA is the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, or GGRF. The GGRF is a $27 billion pool of grant money for funding green investment banks and other community decarbonization nonprofits. In this paper, I explain what the GGRF is, evaluate how effective it is as written, and propose recommendations for how it can be implemented to maximize impact.

The Inflation Reduction Act

The Inflation Reduction Act is a groundbreaking piece of legislation that redefines how the US thinks about the net-zero transition. Passed in 2022 along party lines, the law calls for $369 billion in investments in energy security and climate change, plus $64 billion in healthcare insurance expansions. Jason Bordoff of the IMF calls it “the most significant piece of climate legislation in the history of the United States,” and others share the same sentiment.1 The two other largest pieces of climate legislation ever passed, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill of 2021 and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, combined for under $150 billion in decarbonization funding.

Of the IRA’s nearly $400 billion in climate-related spending, over half is dedicated to tax incentives that make private clean energy investments more favorable. The remaining segments of allotted capital include grants, loans, and greening of federal operations. The IRA is designed not to replace private markets in the drive to net zero, but to mobilize them towards low-carbon and community-friendly investments.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

Included within the $369 billion of IRA climate spending is $27 billion for the creation of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, or GGRF. This EPA-administered grant program is designed to fund green investment banks and other community non-profit financing agencies that aim to reduce emissions within their jurisdictions. According to EPA guidance, “The GGRF will make funding available on a competitive basis for financial and technical assistance for projects that reduce or avoid greenhouse gas emissions and other forms of air pollution, with a particular emphasis on projects in low-income and disadvantaged communities.” The section below explains the role of green investment banks in the US.

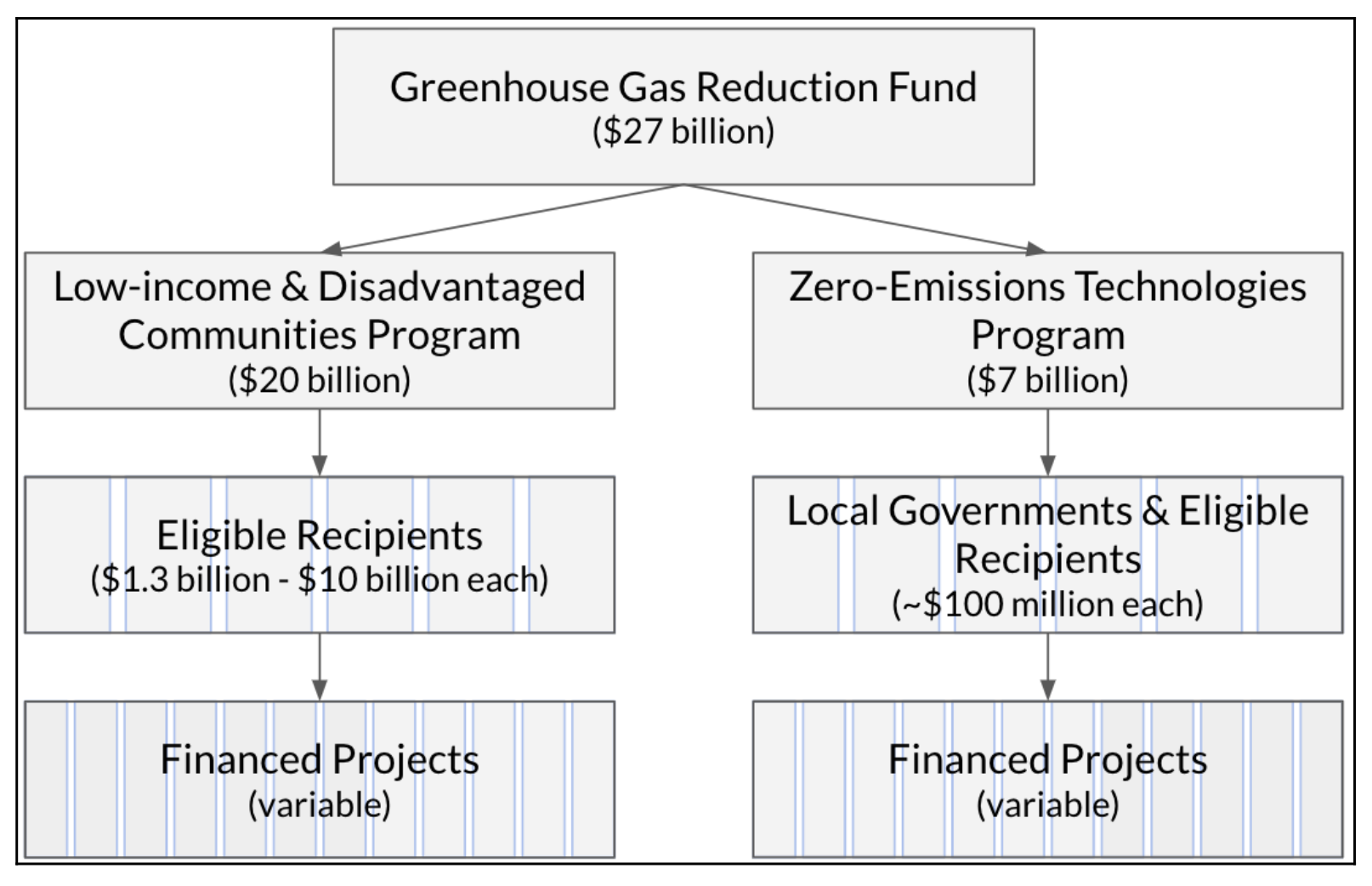

Of the $27 billion in GGRF grants, $20 billion is earmarked for projects benefiting low-income and disadvantaged communities (LIDC), while the remaining $7 billion is meant for investments in zero-emissions technologies (ZET). Banks that receive GGRF funding are expected to be self-sustaining while offering loans and other financing to qualified projects, which are meant to reduce emissions and assist disadvantaged communities. The law also guides grantees to “prioritize investment in qualified projects that would otherwise lack access to financing” to maximize the law’s impact. The GGRF will be implemented in a multi-tiered system, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Structure of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, per initial EPA guidance. Source: Original graphic.

Figure 1: Structure of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, per initial EPA guidance. Source: Original graphic.

Green Investment Banks

Of the “eligible recipients” of grants from the GGRF, the largest group is likely to be green investment banks. Green investment banks, or GIBs, are purpose-driven nonprofit institutions that mobilize financial capital for projects that reduce emissions. Most American GIBs, such as the New York Green Bank, Connecticut Green Bank, and Montgomery County Green Bank, are capitalized by public dollars. The purposes of these green banks are typically to finance emissions-reduction projects, while also crowding in private investment. The mission statement of the New York Green Bank, for example, is “to accelerate clean energy deployment in New York State by working in collaboration with the private sector to transform financing markets.”

GIBs typically fund projects across a range of sizes, depending on the size of the GIB. Larger GIBs like New York’s, or even national-scale GIBs like England’s, frequently provide financing for clean energy projects or major green building projects. In contrast, more local GIBs, like the Montgomery County Green Bank, typically offer financing on much smaller scales, including to individual homeowners to make energy efficiency upgrades or install rooftop solar. Larger GIBs have the advantage of scale, while smaller GIBs have the advantage of granularity and community experience.

In addition to GIBs, other community nonprofits may be eligible for GGRF funding. Community development financial institutions, which are local-scale nonprofits dedicated to investments in their communities, may also meet the criteria for GGRF grants.

Analysis of the Effectiveness of the GGRF

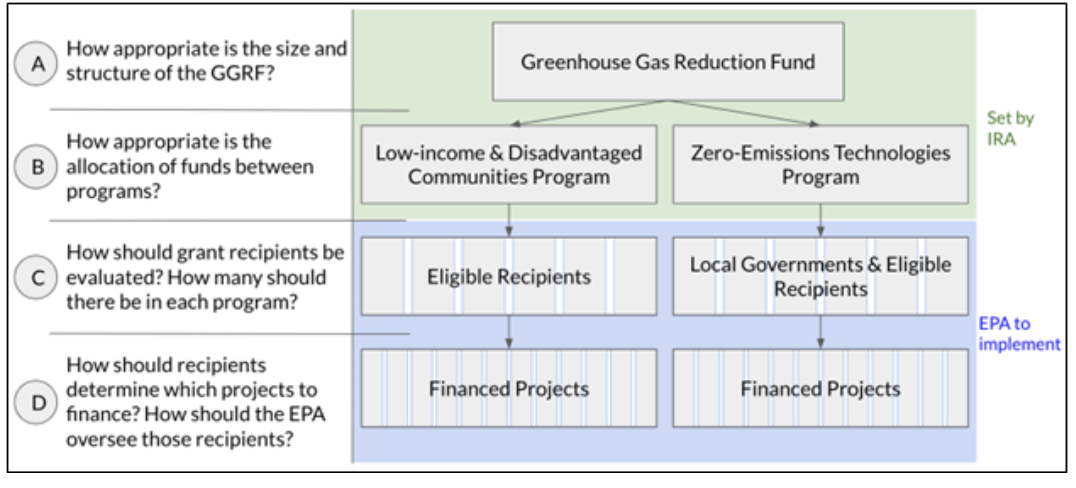

In the second section of this analysis, I answer key questions at each of the four tiers of the GGRF system. I begin by evaluating the appropriateness of the size and structure of the GGRF by contextualizing it in the broader world of green banking. Next, I discuss the appropriateness of the division of the $27 billion between the low-income and disadvantaged communities (LIDC) program and the zero-emission technologies (ZET) program. Third, I share input on how the EPA ought to award grants within each of the two programs, including the optimal number of recipients. Finally, I offer criteria that the EPA should require in financed projects and propose a series of reporting mechanisms to ensure accountability.

Parts A and B are about the first two tiers of decision-making in the GGRF; these structuring decisions were already made in the codification of the IRA. Therefore, the first two parts of this section are more a reflection on the likely impacts of the GGRF, as opposed to a set of recommendations. Parts C and D, however, are about implementation decisions still being deliberated at the EPA. As such, these final two parts contain a set of recommendations for how to maximize the social and economic benefits of the GGRF. A simplified structure of this section is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Key decision points in the implementation of the GGRF. Source: Original graphic.

The Size & Structure of the GGRF

Twenty-seven billion dollars will be a complete game-changer for the green investment banking industry in the US. In 2022, all US GIBs and green banking-adjacent nonprofits combined to invest a total of just $1.5 billion, according to the American Green Bank Consortium. For every dollar that these green banks invested, they catalyzed $2.07 of private financing via co-investment, bringing their total investment impact up to $4.6 billion. If the GGRF’s funding can spur private capital flows in the same ratio as existing GIBs did in 2022, it could generate a total of over $83 billion in new climate-friendly investments.

The funding allotted for the GGRF is meaningful not just in the context of green banks, but also in the broader environment of clean energy investing in the US. In 2021, American clean energy investments reached an all-time high of $105 billion, around 8 percent of the global total. By providing public capital and mobilizing private capital both directly and indirectly, the GGRF can dramatically move the needle on climate-friendly investments in just a few years.

It is wise for the IRA to provide funding for regional green banks, as opposed to creating a single national green bank. Some climate-progressive nations, such as Australia and the United Kingdom, have established national green banks. However, these larger banks tend to invest in full companies, large-scale grid projects and other major infrastructure developments. Projects like these may bring benefits for the whole country, but they typically fail to bring as many targeted benefits for LIDCs. Projects targeted towards disadvantaged communities are typically smaller in scale, and localized green banks are more likely than a national bank to undergo the transaction costs for small green projects.

Assessing the Allocation of GGRF Funding

In the IRA, the $27 billion in GGRF funding is split into two programs: a $20 billion fund benefiting LIDCs via green projects, and a $7 billion fund for ZETs. Both programs emphasize the importance of zero-emissions technologies and targeting disadvantaged communities, so there is significant overlap in their objectives. Though there are minor differences in the requirements of eligible projects between the two funds, they serve the same essential purpose: to capitalize local green banks.

Perhaps even more impactful than the overall increase in green investments, however, is the concentrated investment in emissions-reducing projects in LIDCs specifically. The $20 billion in GGRF funding earmarked for such target communities far exceeds the total investment in those same communities that American GIBs generated – a mere $1.2 billion. The GGRF may well spark over $60 billion in green projects in LIDCs. If the $7 billion in ZET funding also favors investment in disadvantaged communities, the positive equity impacts of the GGRF may be even greater. GGRF funding can go a long way in helping the Biden administration reach its goal of directing 40 percent of the benefits of federal climate investments to disadvantaged communities.

One key distinction between the two programs is the list of eligible grant recipients. The $7 billion ZET fund may be tapped by state, municipal, or tribal governments, or by other “eligible recipients” (i.e. green investment banks) to capitalize green community investments. These local governments could then use their grant money to capitalize new institutions that finance zero-emissions technology projects. In contrast, no government bodies are eligible for the $20 billion in LIDC funding. Instead, only green investment banks, community development banks and other green financial nonprofits qualify.

Number of Awardees & Criteria for Selection

Awardee Size & Quantity

The most important difference between the LIDC program and the ZET program is the expected grant size. The EPA announced that it intends to allot the $7 billion in ZET funds to around 60 awardees, at an average grant size of a little over $100 million. This size of grant would be particularly valuable for new and existing county-level green banks and community development financial institutions (CDFIs). The average CDFI size in the US was $119 million in 2020, so a single average-sized grant from the ZET program could capitalize a new CDFI focused on zero-emissions investments in LIDCs. A ZET grant could do the same and more for county-level green banks. Maryland’s Montgomery County Green Bank, the best-known hyper-local GIB in the country, held just $24 million of green assets in 2022. A $100 million cash injection could allow it to scale up dramatically and reach more LIDCs in Montgomery County.

In contrast, the EPA proposed allocating the $20 billion in LIDC program funding to just 2 to 15 recipients, at an average grant size of anywhere between $1.3 billion and $10 billion. This funding may go to existing green banks or to state, local, or tribal governments, which could in turn establish new green banks. EPA Administrator Michael Regan is also still considering using these funds to create a single national green bank.

Ultimately, the EPA’s indication that they will fund a mix of smaller and bigger financial institutions is a reflection that different-sized banks offer unique advantages and disadvantages. Broadly, the purpose of green banks is to catalyze financing for projects that the private sector fails to fund on its own. We can simplify the many reasons why green projects lack adequate financing into the following four buckets: (i.) technological risk; (ii.) project development risk; (iii.) offtaker/creditor risk; and (iv.) high transaction costs.

While technological risk is certainly significant in the deployment of novel clean technologies, it generally falls outside the purview of the EPA’s GGRF. Instead, programs like the Department of Energy’s Innovative Clean Energy Loan Guarantee Program help bridge financing gaps for emerging green technologies. Project development risk tends to be highest for larger projects, which may face longer development pipelines and unexpected obstacles. As such, larger green banks may be best suited to bridge financing gaps that arise from projects with large perceived development risk. Finally, smaller banks may be best suited for financing gaps that stem from creditor risk or high transaction costs. Smaller banks tend to be more willing to take on smaller projects, which tend to have higher transaction costs. Banks manage risk in part by diversifying their holdings across many small borrowers, none of which is large enough to cause major financial distress to the bank if they default. Because smaller banks hold less money, they typically avoid making the larger loans that big banks make, which could alone account for 5 percent or more of CDFIs’ total lending. It is therefore sensible that the EPA will use the GGRF to capitalize both large and small green banks.

Larger green banks enjoy the benefits of scale, including easier access to financing, better connections with major investors, the ability to make larger loans, and certain administrative efficiency improvements. In 2022, Australia’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation, its national green bank, made $1.45 billion in loans, ranging from half a million to 200 million USD. These deals have helped mobilize large swaths of private capital and have provided affordable financing for everything from developing cutting-edge technologies to dramatically expanding the electric transmission grid. In addition to providing capital and de-risking large investments, national green banks can also play a major role in educating investors on new asset classes and building trust in emerging industries. More than just correcting market failures in green financing, large GIBs can help build new kinds of financial markets. As such, the indirect financial benefits of active GIBs may span well beyond its own investment portfolio. Broadly speaking, larger institutions tend to fund larger projects that have regional or national benefits. Smaller institutions would not have the reach nor the capitalization to close these large deals that help deploy zero-emissions technologies at scale.

On the other hand, smaller banks offer both granularity of knowledge and a willingness to engage with local stakeholders that national or regional green banks would be unable to achieve. The Montgomery County Green Bank, for instance, works closely with apartment complexes and individual homeowners to finance energy efficiency improvements and solar PV systems. These kinds of projects are characterized by high transaction costs, personal interaction, and the need for knowledge of local situations. A national network of small green banks and green CDFIs could fill many small holes in the financing of the residential adoption of zero-emissions and energy-efficient technologies. Though there may be efficiency losses in this system, they are likely to be matched by equity gains through a wider dispersion of financing to individuals and small businesses.

The problem, however, is that the EPA plans to award the ZET funds to a large number of small grantees and the LIDC funds to a small number of large grantees. This should be reversed. The $20 billion in LIDC funds ought to be sent to many – perhaps 200 or more – county-level GIBs or CDFIs that can more effectively reach members of their own communities. With a smaller focus, these grant recipients can finance projects like apartment energy efficiency retrofits or rooftop solar installations, which much more directly benefit residents of LIDCs. As such, while smaller grants may be less efficient due to higher bureaucratic and transactional costs, they are more likely to catalyze impacts targeted to low-income communities. If the EPA is unwilling to consider a dramatic expansion of the number of recipients of LIDC Program funding, they should grant funding primarily to organizations that in turn commit to creating their own networks of local green banks.

In contrast, the ZET funds should be distributed to a small number of larger-scale green banks. This $7 billion is earmarked for zero-emissions technologies. In other words, while assisting LIDCs is still considered, the top priority is to scale up clean technologies as quickly and as widely as possible, so both administrative efficiency and larger deal size are advantages. Larger banks are better equipped for this work, as they can finance utility-scale renewable generation and transmission projects. The large New York Green Bank, for example, typically makes investments in the $10 million to $50 million range.

Awardee Selection & Distribution of Funds

The IRA specifies that GGRF funds be distributed “on a competitive basis” – in other words, eligible recipients must apply for grants, and not all applicants will receive money. This is certainly a good thing, as it ensures that only qualified applicants will be trusted with taxpayer funds. But how should the EPA decide which applicants to fund?

In February, the EPA indicated that it would prioritize offering funds to existing green lending institutions with strong track records in early rounds. This makes sense, as it can help ensure that the GGRF grant model works via collaboration with reputable partners and can scale up. It will be far easier to work out any initial GGRF challenges with existing green banks who rely on the funding for scaling-up, as opposed to new green banks relying on the funding for even basic operations. As of March 2023, there were 39 members of the American Green Bank Consortium, which includes all major green banks and similar institutions in the US; these institutions would be the main beneficiaries of GGRF grants in early funding rounds. As the GGRF moves into later funding rounds, however, it should follow the advice of the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank, and capitalize a mix of new and existing nonprofits. New green banks will help fill financing holes in some of the geographies that need it most, so providing funding can help drive some of the biggest impacts here.

Project Selection & Recipient Oversight

Project Selection

Though GGRF grant recipients will have latitude to determine which deals to close, they are expected to fund “qualified projects” – which the IRA defines as either cutting emissions or assisting communities in cutting emissions. The EPA has the opportunity to further clarify the criteria for qualified projects, and they should establish a set of comprehensive criteria. Across both the LIDC program and ZET program, the EPA should ensure that deals made by GGRF beneficiaries fulfill three criteria: (i.) the project could not have obtained competitive financing in private markets; (ii.) the deal mobilizes private financial flows; and (iii.) the project meaningfully reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Initial EPA guidance suggests these criteria will be used in project selection, though they have not shared further information on numerical thresholds for qualifying.

The first criterion ensures that GIBs will meet the metric of additionality. The purpose of GIBs in the US is not to replace private capital markets, but to open new channels of financing for green projects that would otherwise be unfinanced. GIB financing will necessarily be concessionary rather than competitive, at least at the outset. As GIBs establish trust in new types of green investments, the intent is for private investors to enter the space, at which point GIBs can retreat and redirect capital to new project types.

The second criterion is that GIB loans should spur private capital flows to green projects. GIBs may use a range of tools to make green projects more appealing to outside investors, including co-investment under terms that absorb greater risk, credit enhancement via partial loss guarantees, or aggregation and securitization of small assets like rooftop solar systems. In doing so, GIBs can multiply their impact by as much as three times. There may be limited cases in which direct mobilization of private capital flows is impossible, such as novel or small-scale projects. For particularly innovative projects that may pave the way for new technologies and use cases of existing technologies, the EPA should permit limited instances of purely GIB-funded deals.

The third criterion for qualified projects is that they meaningfully reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Emissions improvements will require evaluation on a case-by-case basis, but as a general rule, no GIB-financed projects should lock in additional unabated fossil fuel combustion activities.

In addition to these three core criteria for project selection, grant recipients under each of the GGRF programs should ensure that financed projects fulfill one additional requirement. For LIDC-funded banks, projects should demonstrate positive impacts on disadvantaged communities. The EPA should work with existing green banks and CDFIs to determine an ambitious but reasonable minimum percentage of total investment in LIDCs for LIDC-funded institutions.

For recipients of ZET program funding, projects should finance the development and deployment of zero-emissions technologies, as well as technologies that support the transition to zero emissions, such as battery storage systems. While LIDC funding may be used for low-emissions (but not zero-emission) projects in limited instances, the core directive of the ZET program should be used to prohibit those types of investments. Only truly transformative technologies should be financed using ZET money.

Recipient Oversight

The EPA’s work will not end at the point of fund distribution. Rather, the agency should continue to engage with GIBs to ensure both compliance with GGRF requirements and effectiveness. To simplify the process, the EPA should work with existing green banks to establish a set of clear reporting guidelines for the industry.

These reporting guidelines should cover at least three key measures of success: financial impact, impact on low-income and disadvantaged communities, and emissions reductions. Financial impact should be disclosed in terms of both public capital allocated towards projects and private investment spurred. Impact on LIDCs should be disclosed in terms of dollars invested, along with qualitative descriptions and case studies of the kinds of work that the GIB does for these target communities. Finally, emissions reductions should be reported in terms of metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents avoided. Given that such measurements may be challenging and costly, especially for small institutions, reasonable estimates will suffice here. The EPA should provide technical assistance for measurement and reporting of emissions impacts of financed projects.

These reporting requirements should not be a burden. The American Green Bank Consortium already reports its total investments and investments in LIDCs, and many of its larger member organizations, such as the New York Green Bank, also report avoided emissions. Even the Montgomery County Green Bank, a much smaller GIB, reports the avoided greenhouse gas emissions of its investments annually.

Consistent and clear reporting from GIBs will allow the EPA to evaluate the effectiveness of the GGRF and identify ways to improve allocation of funds. It will also allow the EPA to screen for underperforming GIBs, to which the EPA can then direct technical assistance or evaluate other options. The EPA should also maintain or hire a team of auditors to verify the integrity of the GGRF program, on both a standard and incident-related basis.

Conclusion

The $27 billion in GGRF funding will reshape the green banking industry in the US. With a heavy emphasis on investment in low-income and disadvantaged communities, the program will help drive important advancements in equity en route to the Biden administration’s goal of directing 40 percent of federal investment in climate to those communities. However, the EPA’s initial guidance on the quantity and size of grants is concerning. They indicate that ZET funding will be split among many small recipients while LIDC funding will be split among a few large recipients; to maximize impact, the EPA should do the reverse. As funding is granted, the EPA should also establish an industry standard for financial, equity, and climate impact reporting. Through careful implementation, the EPA has an incredible opportunity to catalyze new clean energy investments in disadvantaged communities and help drive the US to net zero by 2050.

Jack Kochansky is a 2023 graduate of Duke University