IG Farben used to be the world’s largest chemical company until it was broken up in one of the largest antitrust events in history. My recent research explores how the breakup affected innovation activity in postwar Germany.

The 21st century has seen two notable trends: a “big company” is bigger than ever, and the pace of innovation is slowing. Large superstar firms may be responsible for notable innovations now but have the potential to erode innovation incentives later. The classic Schumpeterian refrain of economic growth through “creative destruction” has become murkier recently, as incumbent firms have become increasingly persistent. Are megafirms good or bad for innovation? How do concentrated markets relate to the pace of innovation? If large firms were broken up, how does the breakup impact innovation?

Empirically, the connection between concentration, the presence of dominant firms, and innovation is hard to pin down, which makes policy advice difficult. The concentration level in a market is almost certainly related both to innovation and other factors that impact innovation, making the true effect of competition on innovation challenging to parse. In rare but important cases like the breakups of Standard Oil or AT&T, the government has stepped in to restructure the market, providing opportunities for studying concentration while stripping away potential confounders. One such event was the breakup of IG Farben, once Germany’s largest chemical company.

Rise and Fall of IG Farben

In the early 20th century, IG Farben was one of Germany’s most innovative firms and the world’s largest chemical company. The company was home to three Noble Prize winners, including one for developing the world’s first commercial antibiotics. IG Farben played a critical role in the German innovation system, accounting for 5.8% of all patents by German inventors and up to 16.5% in chemistry. Because of its industrial capabilities regarding synthetic fuel, rubber, and explosives, the firm was critical to the German war machine and the atrocities at Auschwitz.

In 1952, the victorious Allied Powers understood IG Farben’s economic influence as undue potential political power. After a year of deliberation, the Allies broke IG Farben into a dozen small businesses and three large new companies – BASF, Bayer, and Hoechst. BASF and Bayer still exist as global corporations today, while Hoechst is now part of Sanofi, Celanese, and others. The major successors were largely organized following the Allied occupation zones in Germany, each containing major production and R&D facilities of IG Farben. Suddenly, exposure to concentration in chemical markets and technology fields had changed.

The IG Farben breakup is particularly instructive because it was externally imposed and implemented, and because it was unexpected by the breakup target. Typically, breakup cases (and mergers) result from strategic considerations of firms and antitrust authorities that deliberate about the state of competition and potential outcomes – including innovation. In the IG Farben case, breakup enforcement was not done by antitrust authorities but through a series of laws of the Allied High Commission overseeing the post-war administration of Germany. Considerations were strongly related to political factors, first the impression of the war, and later the distribution of IG Farben factories across occupation zones. Further, IG Farben had – before the war – not expected the breakup and had not directed investments according to such expectations. Therefore, the IG Farben case allows drawing conclusions about competition and innovation in a much more rigorous fashion compared to other cases or post-mortem merger analyses. Finally, the breakup had a geographical structure, and redundancy in technology and product portfolio between the successor companies led to horizontal competition. Relative to the breakup of AT&T, where the vertical separation between research unit and distribution network is central for an innovation analysis, the breakup of IG Farben highlights a different, and arguably more relevant, facet.

One way to think about the IG Farben breakup is from the perspective of a merger. Both a breakup and a merger change who owns assets used to produce a good or service. In a merger, the effect on innovation is ambiguous as it depends on the market structure and any synergies the two joining firms might possess. In a breakup, there will be the “new” firms born from the large incumbent and other non-affected existing firms that react to the breakup. Suppose you assume that breakup will increase innovation by the IG Farben successors. In that case, other firms will simultaneously face new competition in the product market and see technology spillovers. Competitors’ choice to strategically respond determines the aggregate impact on innovation from a breakup. Theoretically, the response by outside incumbents would be ambiguous, as technology spillovers increase innovation while product competition may decrease innovation.

Empirical Analysis

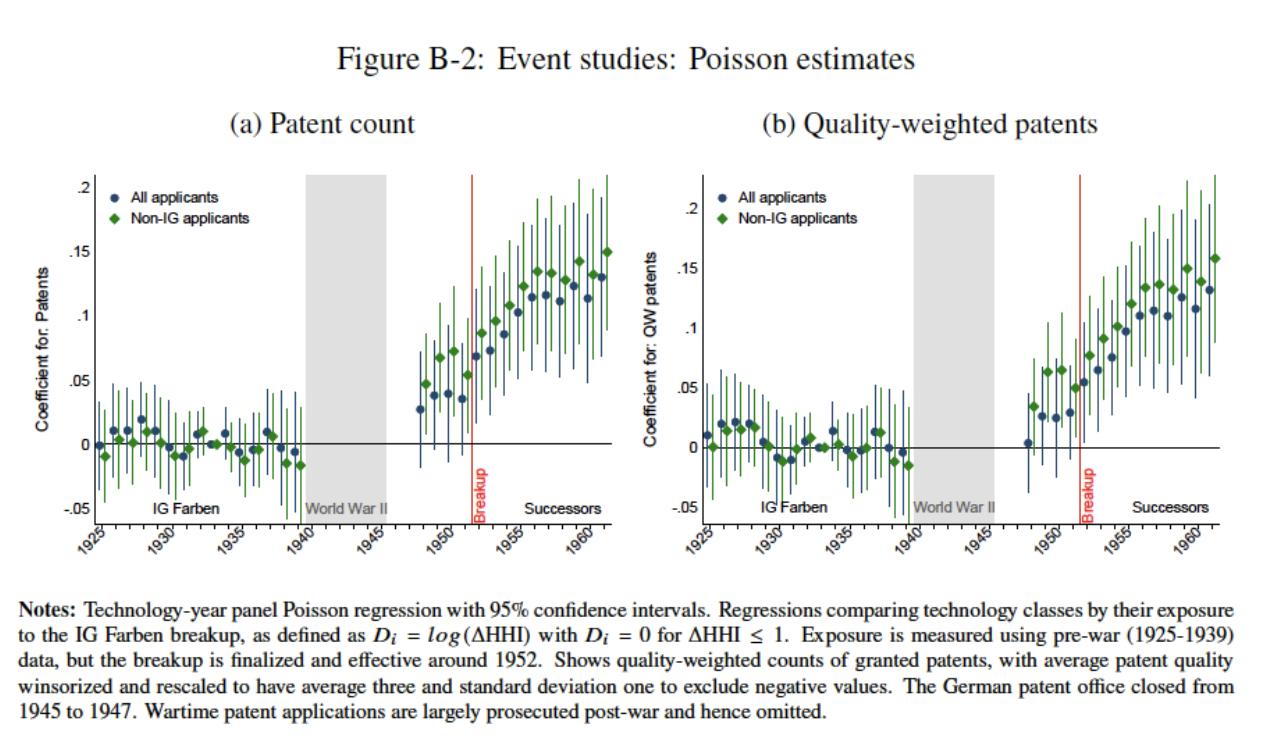

In my paper, I analyze how innovation – measured as the quality-weighted patent count – reacts to changes in concentration caused by the breakup. I measure breakup exposure with the concentration change resulting from the breakup of IG Farben. I consider the hypothetical change if the breakup had been implemented with the same breakup structure but before the war. This method allows me to avoid contaminating the exposure measure with wartime events and post-breakup adjustments. Before 1952, patenting in technologies that were later affected by the breakup of IG Farben was trending in the same way as unaffected technologies. In the post-war period, patterns diverged substantially, suggesting a positive innovation effect from the breakup.

My main empirical results show an increase in aggregate innovation post-breakup. Additional analysis shows that technology spillovers, rather than product market interactions, drive the rise in innovation. To demonstrate this, I examined extremely detailed historical data on the suppliers of thousands of chemical products. This allows me to flag firms exposed to increased competition with IG Farben in their product market. The effect attributed to the technological exposure measure dominates the effect related to the product market exposure measure, suggesting technology spillovers are a likely mechanism of increased innovation.

Of course, there are several potential confounding factors for which a variety of robustness checks are included in the paper. Most importantly, the analysis takes place within chemistry, comparing technologies and firms with different exposure levels. Consequently, the analysis inherently accounts for macro-trends. Nonetheless, in a series of robustness checks and historical discussions, I control for effects of war destruction, Allied occupation and competition policies, and whether a firm operated in the Soviet sector. While there may be other historical details to consider, the observed effects only materialize after the breakup, and the effects are driven by technologies where the breakup increased competition, making it unlikely that any single factor can explain the increase in innovation better than the breakup itself.

If anything, the results here may be best understood as lower bounds, given that the successors of IG Farben did not fully compete, partially due to specialization but perhaps also due to common ownership. In executing the breakup, IG Farben shareholders received stock in every successor, which may have incentivized successors not to undermine each other. Historically, however, they perceived each other as benchmarks and never fully colluded again.

Implications

While the breakup of IG Farben was 70 years ago, the implications of a megafirm breakup remain relevant. Large companies with enormous in-house research investment drive technology and innovation much as IG Farben did in German chemicals. Recent high-profile mergers in the chemical industry like ChemChina-Syngenta, Dow-DuPont, or Bayer-Monsanto only underscore the importance of understanding the relationship between competition and innovation. In particular, this paper highlights the importance of technology spillovers and the need to analyze merger and breakup effects beyond the directly involved firms. This paper additionally reveals some areas for further research. In the United States, large platforms are often the subject of breakup discussions. Whether the findings of this setting apply is undoubtedly an open question, especially since platforms have pronounced network effects.

The history of IG Farben tells the story of a successful government-mandated breakup and opens questions about the role of such breakups as a last-resort instrument in antitrust policy toolkits. It must be noted that the one-off nature of such a breakup is crucial to the theory and mechanism behind the positive innovation effects seen with IG Farben. A policy of repeated breakups may reduce incentives to invest in innovation or grow. Even in the IG Farben case, the German government later introduced formal competition legislation, like the US model, that committed to a policy environment without further breakups. Nonetheless, the IG Farben case highlights the importance of market and technology competition and a robust antitrust policy for innovation.

Felix Poege is a Postdoctoral Associate at the Technology & Policy Research Initiative, Boston University.

This post is adapted from his paper, “Competition and Innovation: The Breakup of IG Farben,” available on SSRN.