The democratization of finance is the self-proclaimed noble cause that Robinhood1 is pursuing by enabling commission-free investing for everyone. However, recent events revealed that the old saying “if it’s free, you are the product,“ has been successfully implemented in the retail investment world. In this article, we cover the recent GameStop fiasco, Robinhood’s business model, and what it means for a modern retail investor.

GameStop Fiasco

It all started with GameStop (NYSE: GME), a US video game retailer, and initially, a small group of retail investors that liked the stock. These retail investors used chat groups, most notably the WallStreetBets (WSB) forum on Reddit, and their investment platforms, such as the popular Robinhood app, to drive up the price of GameStop shares.

At the time, GME was massively shorted and the WSB community identified the opportunity to trigger a so-called short squeeze. This is when the price of the stock goes up and the shorts, in this case a number of hedge funds, have to purchase additional shares to close their posistions which drives the share price continuously higher. As a result, GME went from $10 in October 2020 to over $325, causing the hedge fund Melvin Capital Management to lose 53% of $12.5 billion in assets under management. As a result, Melvin received an emergency liquidity injection of $2.75 billion from Citadel LLC and Steve Cohen’s Point72 Asset Management2.

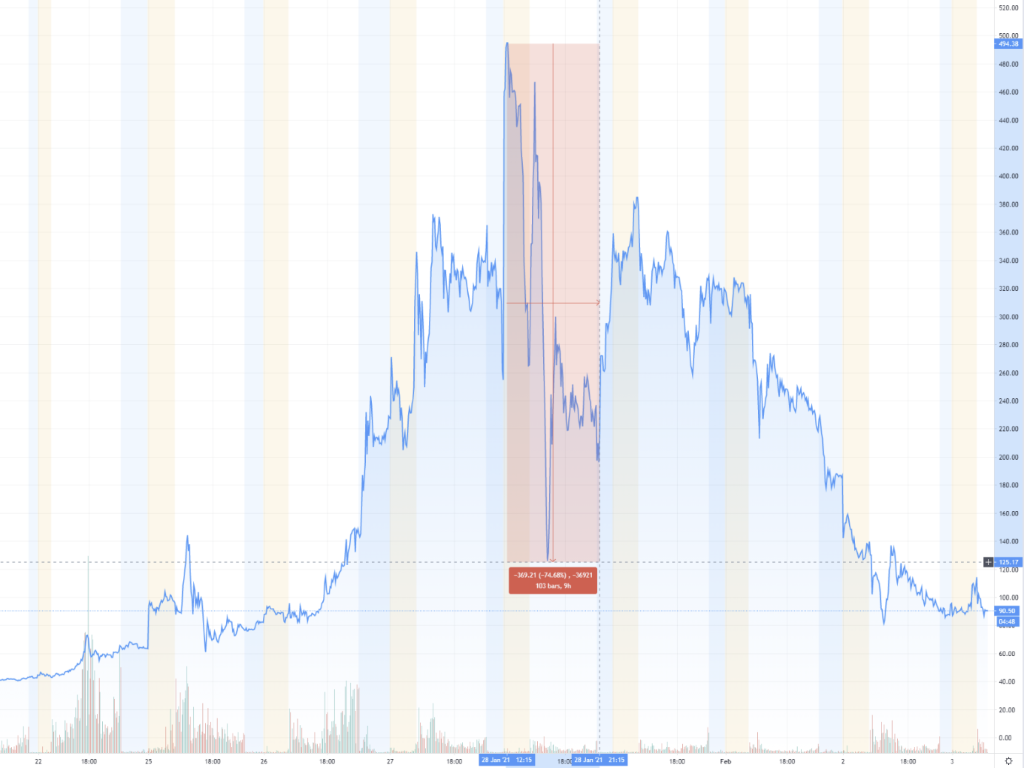

The price continued to trend higher with more and more investors joining the GameStop frenzy, with the stock reaching almost $500 on January 28th. Then on the 29th, something unprecedented happened. Robinhood and multiple other platforms restricted trading for GameStop and some other stocks prominent in the WSB forum, such as AMC Entertainment, Nokia, BlackBerry, and Pearson. More precisely, Robinhood halted the buying of GameStop shares but continued to allow the selling of shares. As the major trading platform for most WSB traders, Robinhood’s decision caused a drastic sell-off of the GameStop shares by almost 75% (see Figure 1), arguably saving Melvin, Citadel LLC, and Point72 billions of US dollars.

Figure 1 – GameStop stock chart, own research.

This decision caused an immense outcry, reaching the highest political levels (Figures 2 and 3)3, and was perceived as active market manipulation by both sides of the fight. On one hand, hedge funds claimed market manipulation by the retail investors, organized through social media. On the other hand, Robinhood’s restriction caused a backlash from many retail investors, who filed a class-action lawsuit against Robinhood within hours, alleging no “legitimate reason” for blocking the purchase of GameStop and other stocks.4

Figure 2 – Robinhood comments from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ted Cruz.

Figure 3 – Congressional complaint by Paul A. Gosar, Member of Congress.

Why did Robinhood halt the trading that caused such a public outcry, alienating their retail “customer base”, and potentially bringing class-action lawsuits and congressional hearings? The official version is that Robinhood was forced to either stop trading or post more collateral to the clearinghouse. Due to the high volatility of GME, the National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC), the clearinghouse for U.S. equities, required a $3 billion deposit, which Robinhood was unable to cover. Later, NSCC agreed to reduce that figure to $700 million as long as Robinhood restricted trading of certain stocks. Consequently, Robinhood halted GME trading. The halting raises several concerns, from the perspective of both market transparency and retail investors who got the short end of the stick.

First, the requirement from the NSCC seems arbitrary given the substantial initial demand of $3 billion and eventually a much smaller amount of $700 million. Why did the NSCC take such drastic action on short notice? Moreover, what was the process used to formulate and execute such a market moving restriction?

Second, protecting retail investors is supposed to be one of the key policy goals of securities regulation; who represented their interests in this fiasco? If there was a general concern of market manipulation, why were only buy orders restricted? These are a few of the key questions that will hopefully be uncovered over time. Nonetheless, the behaviour of various market actors, including Robinhood, left many retail investors with a bad taste.

Third, Citadel LLC, which lost billions of dollars by shorting GME, has been involved at multiple levels in this trade. Citadel5, a hedge fund, and Citadel Securities,6 a market maker, were both founded by Ken Griffin. As a market maker, Citadel Securities provides liquidity and trade execution to retail and institutional clients. One of its clients is Robinhood, to which Citadel paid more than $195 Million in Q3 2020 alone for the right to execute Robinhood’s customer trades (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – Robinhood revenue by market maker7

Robinhood’s Business Model

Robinhood’s business is premised on “payment for order flow,” enabling Robinhood to offer commission-free investing. 8 This is the compensation that the market maker (e.g. Citadel Securities) pays the brokerage firm (Robinhood) for routing trade execution through them. According to the Financial Times: “Citadel Securities pays tens of millions of dollars for this order flow but makes money by automatically taking the other side of the order, then returning to the market to flip the trade. It pockets the difference between the price to buy and sell, known as the spread.”9 However, the spreads have been narrowing so that market makers like Citadel derive most of their profits from playing both sides of as many trades as possible.10 Through the order flow data, Citadel has access to detailed data on the supply and demand of stocks, and they use this knowledge in their automated high‐frequency trading 11 to cash in on the retail trades.12 Tim Welsh, the founder and CEO of wealth management consulting firm Nexus Strategy, calls this business model a “huge conflict of interest for these free trading platforms.”13 Returning to GameStop, restricting retail buy orders drove the price down by almost 75% and saved Citadel billions of dollars.

Enforcement Agencies’ Reaction

Enforcement agencies should represent the interest of the “public” and investors, including retail investors. It thus came as a surprise when Allison Herren Lee, the acting chairwoman of the SEC, called for an investigation of retail investors and alleged market manipulation.14 Janet Yellen, the newly appointed Secretary of the Treasury, also called for a meeting with the SEC, the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission to investigate the GameStop situation.15 We await the outcome of these inquiries. However, one should not forget that Yellen received a sum of $810,00 from Citadel for three speeches in 2019 and 2020.16 Despite receiving an ethics waiver from lawyers before calling the meeting,17 the investigation led by Yellen sparks understandable controversies.

Lessons for Retail Investors

The GameStop situation, specifically the retail investor versus hedge fund battle, requires no additional regulatory scrutiny if all actors operated within proper regulatory frameworks. The underlying issue, however, is far more profound, as it embodies the generational discontent against the financial “establishment.” Accordingly, a regulatory investigation will not addresses this fundamental issue; it will only aggravate existing tensions. This example should be used as a platform for both sides to discuss and reform financial market conditions. A free-market system cannot be built on a few institutions that can effectively act as the central gatekeepers, and in this case gatekeepers of the rich.

We already see a growing movement of mainly younger investors who actively leave the financial system into alternative decentralized systems, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum-based Decentralized Finance (DeFi) applications. However, creating such alternative systems cannot be the long-term solution. Lately, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are increasingly integrated into the existing financial infrastructure, with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency allowing regulated banks to settle payments in cryptocurrency 18 and public companies putting Bitcoin on their balance sheets.19 In this context, Bitcoin is seen as a decentralized store of value, an inflation hedge against the dramatic recent monetary expansion, and “sound money” outside the hands of the government. DeFi is a term used for blockchain-based protocols, products, and platforms that serve as alternatives to traditional financial infrastructure. DeFi applications have exploded, with a current market cap of over $38 billion20. Although DeFi is currently being developed in the regulatory grey zone, it has the potential to challenge, improve, and equalize existing market structures and architectures.

The regulation of these alternative assets and architectures provides an ideal ground for reflecting and redesigning the existing market system and address tensions in a proactive way. This situation is not about applying legacy regulatory frameworks but proactively designing the free market systems of the future to prevent systematic issues from spinning further out of control.

Dr. Alexandra Andhov is an Assistant Professor in Corporate Law & Lawyer, Faculty of Law, University of Copenhagen

Marco Schletz is a PhD Fellow at the UNEP DTU Partnership, Technical University of Denmark