This post is the latest in our special issue: “Climate Change and Financial Markets – Risk, Regulation, and Innovation.” To learn more about the special issue and the work of the Global Financial Markets Center around climate change and financial markets, please read the special issue’s introduction here. And to review all The FinReg Blog posts that touch on climate change, go here.

Climate change is having an indelible effect on the environment and our quality of life. Summers are getting hotter and longer, hurricanes more intense, and cities such as Miami Beach are experiencing sunny day flooding during high tide. Coastal cities may have to be abandoned because of frequent flooding and storm activity. Increasingly, people are realizing that unbridled human activity is emitting more carbon into the atmosphere, which is endangering our climate and the nation’s capital stock. This is an important issue that needs to be addressed with a greater sense of urgency, especially given the long-term costs and consequences for the future generations.

Addressing climate externalities using a carbon tax

Climate change is rife with externalities, meaning that there are substantial external costs borne by non-participants in activities that emit carbon. For instance, if persons A and B transact in a business deal that ends up costing persons C and D who are non-participants in the deal, then C and D are bearing an external cost not of their making. The question then is who should pay for the externality? Perhaps the most hotly debated externality today is the impact of human activity on climate change. Overwhelming evidence and scientific consensus, such as the one published on NASA’s website, demonstrate that climate change is real and that warming trends over the past century are due to human activities that emit greenhouse gasses. The fossil fuel industry, among others, objects to these findings, partly because regulations designed to reduce emissions would constrain its profits and potentially threaten existing jobs.

The Climate Leadership Council, whose members include high ranking former government officials and several Nobel laureates in economics and finance, contend that although the extent to which climate change is caused by human activity can be questioned, the costs associated with warming on future generations—an externality—are so severe that they should be hedged by regulating current activity. They suggest that any solution should incorporate the conservative principles of free markets and limited government. For example, they recommend a gradually increasing carbon tax that is tax-neutral at the macroeconomic level by returning the tax proceeds to the citizenry in the form of dividends.

Efforts to limit climate change and its effects can both spur and slow economic growth. As mentioned above, the Climate Leadership Council recommends a carbon tax be assessed on firms that pollute; without which profit-focused firms will have little incentive to reduce their carbon emissions. Economic theory states that activities that generate costs only borne by third parties will be over-produced and underpriced. A carbon tax will remedy this distortion. To help gain voter acceptance, the Council proposes redistributing the revenue generated by the tax in the form of a dividend that is paid to each citizen. At $40 per ton of carbon, the annual dividend is estimated at roughly $2,000 per family of four.

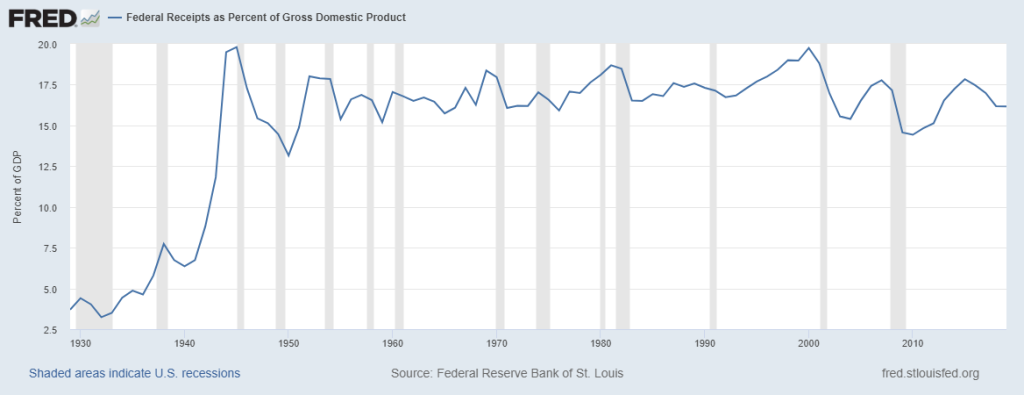

Rather than pay a dividend, economists Jason Furman and Larry Summers recommend spending the money on curbing climate change in addition to borrowing the necessary funds to get the job done. During a recent TV interview, Larry Summers opined that the U.S. is under-taxed and might have to raise taxes at some point. The table below shows that federal tax receipts are less than 17% of GDP, while in the past they have been almost 20%.

However, taxes can be an impediment to economic growth because they curb consumption spending and investment spending, which accounts for the great majority of U.S. GDP. On the flip side, developing and adopting new technologies and processes to combat climate change may lead to a flurry of economic activity and higher economic growth. This job-creating aspect of reducing greenhouse gases was a major aspect of the recently proposed Green New Deal in the U.S. A carbon tax will spur both the private and public sectors to adopt carbon emission reducing measures.

A carbon tax alone is not enough. Addressing climate change could easily cost in the trillions of dollars. Expenditures to combat its effects fall into three major categories; (1) adaptation (2) prevention (3) continuous repairs. While the private sector will pay for some of it, the lion’s share of spending will fall on the public sector. So, will financial markets finance a deficit that will significantly exceed one trillion dollars annually? Excluding the spending on COVID-19, the Congressional Budget Office projects the federal budget deficit to exceed $1 trillion each year for the foreseeable future, and that is with negligible government spending on climate change.

Low interest rates: a prime opportunity for climate-related investment

Low interest rates present a great opportunity to minimize the financing costs associated with addressing climate change. Interest rates have remained low in the face of deficits that will soon exceed 4% of GDP. The 30-year Treasury bond is currently paying a 1.5% nominal interest rate. The dollar is in the enviable position of being the world’s primary reserve currency and there seems to be an insatiable worldwide demand for it. This puts the U.S. in a position of being able to borrow significant sums at unusually low interest rates and tackle climate change head on.

Yet, according to The Economist, economic paradigms eventually do come to an end. The dollar’s reign as the primary reserve currency could be threatened causing the demand for it to drop and interest rates to rise. If rates eventually rise, the U.S. could find itself under greater fiscal pressure to service debt and may be unable to handle another crisis that requires significant fiscal outlays. The saving grace under such a scenario is the Federal Reserve stepping in to “print” money by buying the necessary amount of Treasury securities to keep interest rates low. This is the most powerful tool in the Fed’s toolkit and should be used judiciously. As long as international alternatives are unavailable, it would be safe to assume that a flight from the dollar will not happen in the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

With natural disasters growing more frequent and more intense, we cannot ignore the risk of future shocks to the global economy that are greater than the ongoing pandemic. The current low interest rate environment presents a great opportunity to minimize the financing costs associated with addressing climate change. Borrowing a trillion dollars specifically earmarked for fighting climate change is a sensible policy.

We may soon be at the tipping point in terms of addressing climate change before it is too late and raising the necessary funds at historically low interest rates. Inaction only serves to increase the costs of potential solutions. It is time for governments to realize the enormity of this challenge and act accordingly.

Murad Antia and Arun Tandon are members of the Finance Department, Muma College of Business at the University of South Florida.

This post is adapted from their paper, “The Impact of Climate Change on GDP Growth and National Wealth,” which is published in Rutgers Business Review (Vol. 4, No. 2, 2019) and available on SSRN.