Now that the historical significance of this killer has been elaborated, how does it actually work? How does it become resistant to standard antibiotics? Such questions are our next topic in this unit.

The Basics: What are Bacteria?

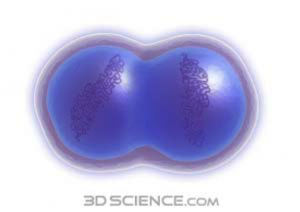

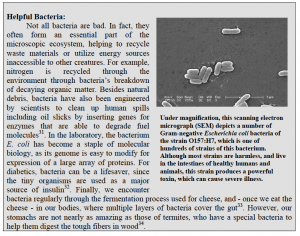

Bacteria are a diverse set of microscopic organisms, exhibiting a staggering range of sizes, shapes, and behavior. However, they all share a few common traits: all bacteria are single celled, or unicellular, and usually replicate by binary fission, splitting into two identical copies of themselves when they reach a certain critical size23,24. Other methods of reproduction are also possible, including conjugation (in which one bacteria gives another a piece of DNA through a tentacle) and spore formation, in which the bacteria enters an inactive phase until they find a host to infect23.

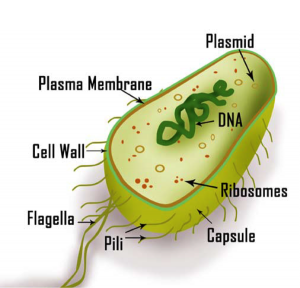

Unlike our own cells, bacteria have no nucleus, and their genetic material is contained in a circular chromosome of DNA24. Some bacteria have additional genetic material contained in plasmids, rings of DNA that are separate from the organism’s chromosome and capable of replicating independently25. Because they lack many familiar organelles, including the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, bacteria can be quite small, a trait that often aids their invasion of the body’s recesses24. However, they do usually have a cell wall, a layer outside the plasma membrane that helps bacteria maintain structural rigidity and determines their sensitivity to anti-biotic agents24.

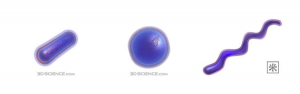

Bacteria take on many shapes, including rods, cones, spheres, “commas”, branched cells, and spirals24. Many times

conjugation.

bacteria are classified according to their shape. For example, Bacillus bacteria are rod-shaped, Cocci refers to a spherical bacterial cell, and Spirochetes assume a sprial-form (such as that of Syphilis bacterium)24,26. Additionally, bacteria are often classified based on their reaction to a chemical test developed by Hans Christian Gram, a 19th century microbiologist who discovered that some bacterial walls absorb a dye (crystal violet) better than others27. This test – named the Gram Test in his honor – is often used as a method of classifying bacteria.

Not all bacteria have a cell wall. For those that do, the wall is often a collection of porous sugar-protein molecules called peptidoglycans, which, unlike the cell membrane, is permeable to most substances in the surrounding environment28. These bacteria are positive for the Gram test29. However, if the peptidoglycans are surrounded by an extra layer of fat molecules, they are negative for the Gram test29. Some even more complex cell wall structures are possible, including that of M. tuberculosis (as described below)29,30.

Comprehension Questions:

1. What are some different shapes bacteria can have?

2. What are the components of the bacterial cell wall? How does this affect the Gram Test?

3. What are some non-pathogenic bacteria?