Author: Greg Lyons Page 1 of 2

I found Nadja Sayej’s “Programming Computers with Dirt” article fascinating. As a programmer myself, I was intrigued at the possibilities of harnessing the Earth’s natural resources for operating a computer. Reading the interview with Martin Howse, the artist behind Earthboot, brought my thoughts back to our earlier Jean-Francois Blanchette reading, “A Material History of Bits.” Blanchette’s paper reinforced the physical grounding that lies beneath all computing – the fact that information must be stored in bits as physical on-off switches somewhere on some tiny chip. Assuming the computing industry continues its rapid growth, what will happen when we run out of resources to make these chips and store this information? Our Earth has a limited supply of silicon to make the integrated circuits that these microchips need, and there is limited physical space on Earth to host computer clusters. We have enough concern for overpopulation of humans, let alone overpopulation of information!

Projects like Earthboot suggest natural solutions for more efficient information storage. Earthboot uses naturally-occurring electricity for booting up a computer, and perhaps this linkage between computers and natural Earth phenomena could prove promising (and more renewable than current materials used). Scientists at Harvard have already made groundbreaking progress in using DNA as a sort of digital storage device, fitting approximately 700 terabytes of data in a single gram of DNA (Anthony). In the near future, it could be commonplace to see large amounts of data encoded within strands of DNA, which would bring new meaning to the idea of information being alive.

It is easy to get caught up in the allure of a new technological era, and to consume massive amounts of resources in the process of development. However, as a society we have a responsibility to find long-term sustainability for our technological dependencies. Experimental projects like Earthboot provide a fascinating glimpse into future linkages between nature and computers.

Sources:

Anthony, Sebastian. “Harvard Cracks DNA Storage, Crams 700 Terabytes of Data into a Single Gram.” ExtremeTech. ExtremeTech, 17 Aug. 2012. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.extremetech.com/extreme/134672-harvard-cracks-dna-storage-crams-700-terabytes-of-data-into-a-single-gram>.

Blanchette, Jean-Francois. “A Material History of Bits.” Web. 10 Oct. 2014. http://polaris.gseis.ucla.edu/blanchette/papers/materiality.pdf

Sayej, Nadia. “Programming Computers with Dirt: Earthboot Powers PCs with Geological Energy.” Motherboard. VICE, 22 Oct. 2013. Web. 14 Nov. 2014. <http://motherboard.vice.com/en_uk/blog/programming-computers-with-dirt-earthboot-powers-pcs-with-geological-energy>.

https://docs.google.com/file/d/0ByoueGSWXluVVUtHYnRJVEg4YnM/edit

Read it! It’s a little long but I promise it’s worth it. One of my personal favorite short stories.

Ebocloud provides a fascinating look into the powerful effect that social networking through technology can have on human psychology. I was interested in the way that being a part of the ebocloud network manipulated people’s own perceptions of reality. When initially describing the merit system to Ellie in Part 1, Jared describes how “faking being a good person week after week” leads to one day waking up and “realizing you are good” (Moss 59). In this sense, ebocloud functions as a technology that turns people from selfish into selfless. Perhaps, then, the surface objectives of ebocloud are subordinate to deeper, more significant objectives. The ebocloud network is not about the specific deeds being done – while practically useful and critically important to the individuals receiving help, these individual tasks are not as important as the collective effects cultivated by the cloud. Ebocloud has the power to open individuals’ eyes to the world beyond their own daily existence and open them up to a world of possibility in serving others.

However, with such a powerful collective effect, there are dangers to ebocloud. Later in the novel, Desalt describes to Ellie how “devoting yourself fully to the common good” results in “losing yourself”, and Ellie ponders whether the human race is “doing away with our individuality” (Moss 195). In creating all of these connections between humans to elevate our collective power as a group, do we lose something more important than we gain? Perhaps in following this sort of utilitarianism (happiness for the greatest number of people), people lose track of individuality and the value of personal pursuits. This reminds me of Fight Club (originally a book by Chuck Palahniuk, but I have only seen the David Fincher film). Fight Club deals with individuals who seek to break from conformity of society – yet in forming a collective rebellion against society, they end up relinquishing their individuality yet again. Blind conformity in any scenario can be dangerous, regardless of the motives. The ebocloud network has significant power to increases selflessness among humans, but is selflessness what we really want?

Works Cited:

Fight Club. Dir. David Fincher. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2000.

Moss, Rick. Ebocloud. New Orleans: Aqueous, 2013. Print.

My project will examine non-linear narratives in several different mediums to fully examine the implications, both literary and artistically, of this design choice. I will analyze Ba and Moon’s graphic Daytripper, Christopher Nolan’s film Memento, and another film or video game that remains unselected. My media element will consist of visual timelines for each work that aid in understanding the flow of the plot and are seamlessly integrated into the essay. I plan to study how the effect of non-linear structures mimics and reflects imperfections and affordances of human memory. The main question I am tackling is – why do artists and writers choose to employ non-linear narratives, and what does it add (qualitatively) to the experience of viewers/readers? My goal is to find common links shared across different mediums and stories that use non-linear plotlines, and to relate these connections to the way that the humand mind perceives reality.

Deena Larsen’s Firefly is a fascinating electronic literature piece that enriches and adds valuable depth (quite literally) to a traditional structure of written poetry to augment the reader’s experience. Although Firefly may at first appear to be a normal poem, Larsen challenges typical linear narrative structure and utilizes Flash hypertext to add interactive layers to the piece. The digital poem consists of six stanzas, each “five lines ‘long’ and six lines ‘deep’” (Larsen). The “depth” derives from the hypertext – each line of the stanza is clickable and rotates between six possible strings of text for that line. Larsen uses this affordance to take Firefly beyond the bounds of linearity and provide self-described “multi-dimensional spaces for meaning, subtext, and context” (Larsen).

Creating a meaningful reader experience is critical for crafting a successful electronic literature project, and Firefly puts the reader experience first and foremost on its list of priorities. Larsen strikes an effective balance between authorial intent and open interpretation by providing a malleable, responsive work that still manages to fit within the atmosphere she desires. The content itself of Firefly exists within a certain haunting, mysterious aesthetic. Larsen uses a dark, murky color scheme of greens and browns for the background, with eerie brick structures reminiscent of a graveyard. The poem itself describes a narrator’s fleeting nighttime encounter with a firefly, and the narrator heavily romanticizes the firefly while giving vivid descriptions of its movements. There is a certain level of anthropomorphizing, and the narrator appears to view himself and the firefly as equals. On the surface it appears to be an insignificant encounter, yet the narrator’s heartfelt musings show that it is clearly a powerful moment for him. In one possible reading of the poem, the narrator recounts, “I pour a life’s memories out before him like spilled wine to break the silence” (Larsen, Stanza 5). Larsen evokes sympathy from the reader, as she describes the narrator’s struggle to communicate with the firefly. The final stanza is arguably the strongest of the poem, with one possible reading being “The moment breaks as if nothing had existed…leaving nothing inside to remember what lies afterwards” (Larsen, Stanza 6). A chance encounter that appears trivial ends up leaving a gaping emptiness for the narrator, and it is difficult not to empathize with his sadness. It is true that Larsen leaves it up to the reader to change the lines to create powerful emotional messages (the two quotations referenced above are manipulated stanzas rather than the default configurations). However, these possibilities are specifically designed to remain in line with the gloomy ambience that Larsen seeks to establish. In her book Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary, N. Katherine Hayles describes the challenges that E-Lit writers face in trying to incorporate “conventional narrative devices such as rising tension, conflict, and denouement in interactive forms where the user determines sequence” (Hayles 16). Larsen takes these challenges head-on, and provides an interactive experience that is constructed to maintain its poignancy regardless of the user’s choices.

The power of Firefly is in its unique combination of surface simplicity and depth of meaning. The interchangeable lines are masterfully crafted and arranged such that any permutation provides a reasonably readable stanza. Larsen is successful in staying well-grounded and not trying to do too much with the project. That is not to say that her work lacks effort – at a UND Writer’s Conference in 2010, Larsen admitted to spending six months on Firefly, explaining that “getting everything to fit together takes a long time because you actually do have to sit there and think about these things” (Larsen 2010). By pouring so much effort into a small, focused work, Larsen creates a clean and rich final product. The depth of the project and the countless possible arrangements for the poem make it an E-Lit piece that is worth re-visiting many times, as each read will surely be a different experience.

Firefly certainly qualifies as electronic literature, and its literary merit is evident, though its technology and interface are not particularly ambitious or avant-garde within the realm of modern E-Lit pieces. Indeed, the project has an extra dimension that adds depth beyond the scope of traditional poetry, but at heart it is still simply a collection of words. The project could reasonably be re-created in a physical representation, but it would be more cumbersome to navigate. It is also important to bear in mind that Firefly was created in 2002, and making hypertext with flash is quite passé now while it might have been fairly innovative for a project at the time. It was likely for the better that Larsen was not overly ambitious in writing Firefly, and perhaps the project medium and structure itself can even be seen as a metaphor for the story it contains. The project’s presentation is simple on the exterior, yet it provides additional layers that add significant meaning and emotional depth. Similarly, the narrator’s encounter with the firefly could have easily been a bland moment in passing, but it turns out to be a beautifully melancholy interaction with unexpected vividness. While some E-Lit focuses heavily on interesting technology and exciting user experiences and perhaps lacks in literary merit, Firefly is towards the opposite end of the spectrum. Larsen’s technology is not flashy in any way, but she utilizes its affordances to their full extent in designing an enhanced poem.

Firefly serves as a valuable example that electronic literature can exist in an augmented digital medium without sacrificing contextual and sub-textual literary meaning. In The Language of New Media, Lev Manovich appears to disparage the merit of electronic literature, claiming that “all new media objects, whether created from scratch on computer or converted from analog media sources, are composed of digital code; they are numerical representations” (Manovich 27). Gould examines Manovich’s position in A Bibliographic Overview of Electronic Literature, arguing that his statements seem to “sever the literary from the work by effectively mathematimacizing e-poetries and e-literatures” (Gould). Gould is correct that Manovich is “rather harsh” (Gould) in his opinions, and indeed his blanket statements are disrespectful to electronic literature writers. The fact that digital literature works are stored as numerical data at the lowest level has hardly any impact on the majority of reader experiences with said works. E-Lit writers design their projects using words just like any other writer, and they choose to take advantage of (and be influenced by) certain technological media. At heart, an e-lit project is still a literary work, and does not deserve to be discredited based on its mathematical representation at the lowest level. Electronic literature works like Firefly should be praised, despite imperfections, for their efforts to push boundaries of scholarly tradition and provide an augmented experience that enables readers to think and feel in new ways.

Works Cited:

Gould, Amanda. “A Bibliographic Overview of Electronic Literature.” Electronic Literature Directory. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

Hayles, Katherine. Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. Notre Dame, IN: U of Notre Dame, 2008. Print.

Larsen, Deena. Firefly. 2002. Web. http://poemsthatgo.com/gallery/fall2002/firefly/index.html.

Larsen, Deena. “Reading: Deena Larsen”. UND Writers Conference. 23 March 2010.

Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

The beauty of Daytripper is in its ability to encapsulate universally-relatable aspects of human nature and jarringly powerful emotions in its short, simple scenes. Ba and Moon are masters of shedding light on the human condition, and through the tangled arrangement of vignettes that make up Bras’s life they are highly effective in creating an emotional connection with readers.

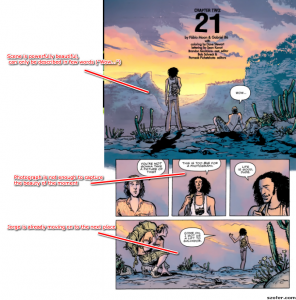

For example, the scene in Chapter 2 where Bras and Jorge overlook a canyon captures humans’ indescribable wonder at nature’s beautiful creations. The two young men can neither describe the view with words (all that Bras can say is “Wow…” (Moon 36)) nor capture the moment with a picture. Most people have experienced the feeling of trying to take a picture of something beautiful and finding that the picture is inadequate, and Ba and Moon do an excellent job of displaying this sense of awe.

Another scene, where Bras’s son watches TV while his father is gone in Chapter 8, is powerful in demonstrating the emotional importance that parents have for their children. The scene appears to reference Disney’s The Lion King, when the death of Mufasa leaves his son Simba alone. This also foreshadows the later death of Bras (which is not much of a surprise by this point in the graphic novel).

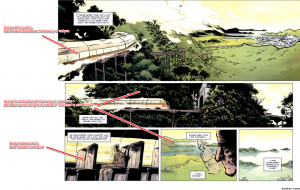

In Chapter 9 an elderly Bras rides the train alone through a mountainous region. Bras has been doing a lot of thinking, and he comes to a sort of revelation while riding the train. Ba and Moon use the passage of the train from the forest into a clear region with excellent views to show the epiphany that Bras has had in clearing his mind. The scene also presents an interesting contrast between the natural beauty of the landscape and the futuristic elegance of the train.

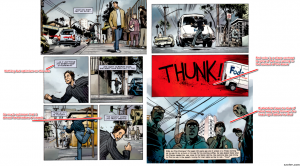

Arguably the most heartbreaking death in the graphic novel occurs at the hands of the truck in Chapter 3. Bras has suddenly become intoxicated with the enchanting possibilities of life, and is literally sprinting to take advantage of all that the world has to offer him. All of this is wiped out in an instant by the truck, and the illustration of the death has an unforgettable blood-red color scheme. For Bras to be so hopeful and optimistic and to have it all sniffed out by a random accident certainly provokes a strong emotional reaction, and reminds all readers of the reality of human mortality and the fleeting nature of life.

Works Cited:

Moon, Fábio, Gabriel Bá, Dave Stewart, and Sean Konot. Daytripper. New York: DC Comics, 2011. Print.

The Lion King. Walt Disney Pictures, 1994. Film.

What does ancient oral storytelling have in common with cloud computing data centers? The connection lies in the fact that information cannot exist without a medium to store and deliver it. Before the invention of writing, human memory was the primary medium for storing information. Stories were passed down through oral traditions, yet these stories were constantly modified and warped as they were passed down, as imperfections in the medium strongly influenced the information. Information was lost whenever a story was told for the last time. The invention and growth of writing revolutionized the way that information was stored, allowing people much greater access (writings of a long-dead author, letters from far away relatives, current events, etc.). Writing increased the lifespan of information, although it was still very possible to lose data – history has seen far too many book burnings.

The advent of computing has brought about another information revolution, but it is important to remember that this data is still bound to physical media. In “A Material History of Bits,” Jean Francois Blanchette argues that bits “cannot escape the material constraints of the physical devices that manipulate, store, and exchange them” (1). Blanchette goes on to describe the mechanisms and processes that are used to store computer data. These mechanisms have again increased the lifespan of information – when information is lost on one system, often it can be recovered through another system. When most people log into Facebook or type in a Google search, they do not consider all of the physical computing systems that are involved in the process of bringing up the webpage on the screen. But the truth is that computing data is very much anchored to physical materials.

Consider a data apocalypse, where every single computer storage system in the world was destroyed (all bits reset to zero). It might seem intuitive that the information would still be floating around somewhere in vague immaterial space (as many people imagine the “cloud”), and that once the computer systems were rebuilt they would be able to dive back into the pool of information. However, if every computer storage system were emptied, then there would be no backups or other way of reclaiming the information. The reality is that once unanchored, the information would drift away like a balloon escaping from a child’s hand, never to be recovered.

Works Cited

Blanchette, Jean-Francois. “A Material History of Bits.” Web. 10 Oct. 2014.http://polaris.gseis.ucla.edu/blanchette/papers/materiality.pdf

While scholars may not yet hold games to the same academic and artistic merit as written literature, it is undeniable that games are attracting more and more attention. Games are constantly evolving and reaching new audiences, and these days they serve a wide range of purposes, from education to fitness. The gaming industry has an undeniably massive influence in the realm of modern media culture – a 2014 study found that US consumers spent over $15 billion on games in 2013 (NPD Group, 2014). In the realm of critical theory, games are gaining further attention as a medium to be analyzed. Games can be evaluated as media through the experiences that they provide for their players, and these experiences are never identical.

For many people, games are a medium providing an escape from reality. This respite from routine can take the form of simple, addictive diversions (think Angry Birds (Rovio)) or massive, immersive worlds (think Grand Theft Auto (Rockstar)). In the former type, players can forget about their lives that seem to be slowly dragging along and can instead fixate themselves on temporary rewards and short bursts of action. The latter type provides a fantasy reality, where players can shed their real identity and take on the persona of an intergalactic conqueror or a powerful wizard. However, as much as these games strive to provide an escape from reality, in many senses they reflect and imitate that same reality. For many players, an immersive fantasy experience is much more powerful if it is believable. In his book Gamer Theory, McKenzie Wark dives into this complex relationship between games and reality. Wark describes the real world as a sort of “gamespace” in its own right – a place guided by “some arbitrary blend of chance and competition” that is “losing, bit by bit, any form or substance or spirit or history that is not sucked into and transformed by gamespace” (Wark 19). While many games may serve the purpose of escaping one’s own reality, players may lose sight of the fact that their escape realities often mirror the characteristics of their true realities.

Not all games aim to provide an escape from reality. Many games seek to augment reality in a way that is both productive and engaging. Fitness games are growing more and more popular, and new technologies like Wii Fit and Xbox Kinect are providing new affordances that allow for effective training capabilities. Educators have long recognized the value of games for engaging the interest of children, but games can be used to improve knowledge in skills in all subjects for all different sorts of age groups. While second graders might play a simple farm animal game to learn about basic arithmetic, adults can use professional, interactive games to learn to speak foreign languages (Sykes). Military and government agencies use games to train individuals for difficult missions (Shaban). Even games meant for entertainment can sometimes be used for practical purposes. For example, sports analysts often use sports video games to simulate and predict outcomes (Robinson). In all of these different examples, games act as a medium to augment existing reality, and they provide engaging and powerful affordances that other media cannot deliver.

Games, no longer a niche hobby for enthusiasts, are making themselves more and more evident in mainstream culture. From an economic standpoint, the gaming industry is a fascinating and influential sector of our modern commercial culture. In 2013, Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto V reached sales of $1 billion in just three days, making it the fastest-selling entertainment product in history (Goldfarb, IGN). Games have demonstrated a remarkable power to influence and invade other forms of media, with countless video games spawning spin-off adaptations as books, television shows, and movies. In his book How To Do Things with Videogames, Ian Bogost describes how games have entered the shared realm of media, claiming that they are “as interwoven with culture as writing and images” (Bogost 7). He reiterates that video games are not just a niche part of culture “meant for adolescents”, but are instead “woven into everyday life” (Bogost 7).

In a purely technical sense, games can by studied as a medium by examining the evolution of game technology over time. From the simple graphics of Atari and Pong to the facial recognition software of modern Xbox Kinect consoles, games have come a long way – and there is no sign of slowing down. Virtual reality appears to be the next frontier for games. VR is compelling for the mystery that surrounds it, and the vast amount of potential that the technology holds. There are parallels between the development of virtual reality and the development of artificial intelligence – both are incredibly powerful fields that still have much to be explored, and both have their own haunting possibilities depicted in media. Films like The Matrix (Warner Bros.) portray a conceivable dark side of virtual reality for humans, yet this sort of portrayal might create more of a sense of excitement than a sense of fear. This sense of excitement associated with gaming is key to its growth, as developers feel a constant pressure to innovate without letting games and technologies get stale. If mediums cannot adapt, they die out (think of telegrams, record players, and VHS). Games are a dynamic and living medium that elude compartmentalization and continue to evolve at all times.

It is precisely this elusive nature of the game medium that makes it difficult to evaluate them in a critical context, although it certainly can be done. For many forms of media, like books, films, and music, consumers of content are very aware of an individual creator or other important person (fans will know who wrote the book, who directed the film, who performed the music, etc.). However, game players do not commonly associate their gameplay experience with a certain individual. The technical complexity involved in developing big-time commercial games usually requires massive companies and teams, and the independent developers who make simple games are not usually concerned with individual fame (following the principles of hacker culture). In games, the lack of a central creator or performer imparting a message is liberating. The focus is shifted to the player’s experience – games provide a world in which players can craft their own unique experiences. Some games, like Bioshock Infinite (2K Games), give players difficult ethical choices to evoke emotional responses. Puzzle games like Portal (Valve) and The Company of Myself (Piilonen) often enrich their problem-solving mechanisms with background stories that give the player a narrative context for gameplay. These enriching experiences vary greatly from player to player, and this is the true essence of games as a medium. Games should be evaluated critically for their ability to create a meaningful experience for the player and for their use of the affordances provided by the specific game technology.

Works Cited:

Bogost, Ian . “Introduction.” How To Do Things With Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. 1-8. Print.

Infinity Ward. Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare. 2007. PC

Nintendo. Legend Of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. 1998. Nintendo 64

NPD Group. “Research Shows $15.39 Billion Spent On Video Game Content In The US In 2013, A 1 Percent Increase Over 2012.” NPD Group, 11 Feb. 2014. Web. <https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/research-shows-15.39-billion-dollars-spent-on-video-game-content-in-the-us-in-2013-a-1-percent-increase-over-2012/>.

Piilonen, Eli. The Company of Myself. 2009. PC

Robinson, Jon. “Pittsburgh 24, Green Bay 20” ESPN.com. ESPN, 1 Feb. 2011. Web. <http://espn.go.com/espn/thelife/videogames/easims?id=6072052>.

Rockstar Games. Grand Theft Auto V. 2013. PC

Rovio. Angry Birds. 2009. iOS

Shaban, Hamza. “Playing War: How the Military Uses Video Games.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 10 Oct. 2013. Web. <http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/10/playing-war-how-the-military-uses-video-games/280486/>.

Sykes, Julie M. ““Just” Playing Games? A Look at the Use of Digital Games for Language Learning.” The Language Educator 8.5 (2013): 32-35. Web.

The Matrix. Warner Brothers, 1999.

Valve. Portal. 2007. PC

Wark, McKenzie. Gamer Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2007. Print.

2K Games. Bioshock Infinite. 2013. PC