The last 24 hours have seen delay after delay for the closing plenary of COP24 as delegates finalize last minute details for the final rulebook. A few final draft texts have been circulating in these last crucial hours as new drafts tighten prose, remove bracketed sections, and finalize the modalities processes and guidelines (MPGs). The latest transparency text reflects a tremendous effort on finding acceptable agreements around flexibility, reporting guidelines, and timelines.

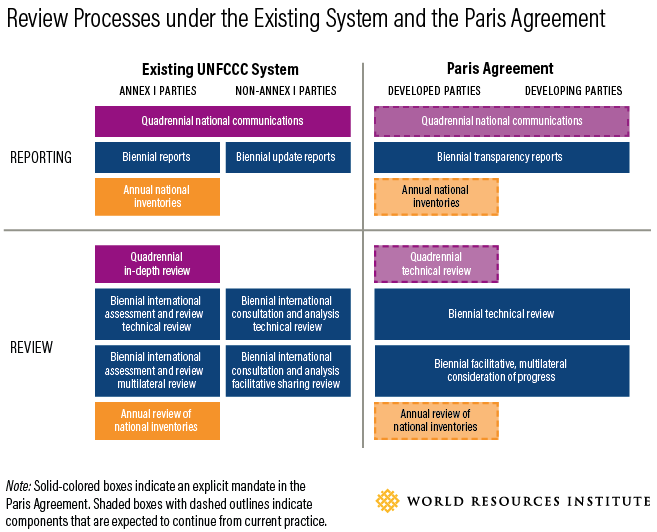

The fight over flexibility produced a fairly balanced approach in the end. Though bracketed MPG guidance referring to common but differentiated (CBD) approaches persisted until Friday, the latest draft has removed all references to CBD. Instead, a nuanced definition of flexibility prevails, but what does that mean? The application of flexibility will be nationally determined, only applicable to developing countries, and should reflect national capacities. Most provisions allow for the application of flexibility in determining the scope, frequency and level of detail in reporting, and the scope of reviews.

The events are over, just waiting for the final rulebook

While that may seem fairly lenient, countries that apply flexibility shall note constraints and time frames for improvement. Developed countries strongly advocated for this second requirement and its inclusion signals hope for moving all countries to a more universal system. Technical experts cannot specifically review determinations to apply flexibility, but they will report areas for improvement in national reporting processes.

On interesting backslide is from Paris Agreement Article 7, which declares all parties shall report inventories and progress on NDCs. The draft text instead “Also decides that the least developed country Parties and small island developing States may submit the information referred to in Article 13, paragraphs 7, 8, 9 and 10, of the Paris Agreement at their discretion.” This is echoed throughout the text.

As for the reporting itself, national inventories for greenhouse gases will be developed in accordance with the IPCC 2006 guidelines rather than the guidelines from 1996 currently used by many developing countries. There is flexibility on what gases need to be covered in the inventories. Traditionally developing countries have only reported on three greenhouse gases. Now if countries mention other greenhouse gases in their NDCs or previous reports, they will need to include them in their inventories. Countries also must report an annual time series of data, improving our ability to see trends and track progress.

The room where it (will) happen

Perhaps the biggest disappointment of the text is the timeline for the new regime. The text “Decides that Parties shall submit their first biennial transparency report and national inventory report, if submitted as a stand-alone report, in accordance with the modalities, procedures and guidelines, at the latest by 31 December 2024.” This means that reports will not be used in the first Global Stocktake, scheduled for 2023, and will leave little time for the NDC revisions due in 2025. There will still be reporting under the old regime up until 2024.

Overall this draft for the Enhanced Transparency Framework has many strengths. Updating reporting guidelines and requiring time frames in light of flexibility allow for movement towards a clearer understanding of our progress towards the Paris temperature goals. For such a contentious topic, it seems, as of now, that the Parties have made great strides towards consensus building. That said – nothing is final until the (once again delayed) final plenary ends and the gavel falls.